Dramatism

Dramatism, an interpretive communication studies theory, was developed by Kenneth Burke as a tool for analyzing human relationships. In this theory, our lives are as if on a stage, setting us individuals as actors on that stage as a way to understand human motives and relations.[1] Burke discusses two important ideas – that life is drama, and the ultimate motive of rhetoric is the purging of guilt.[2] Burke recognized guilt as the base of human emotions and motivations for action.

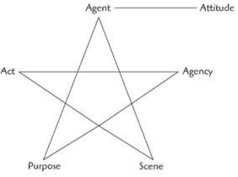

To understand people's movement and intentions, the theorist sets up the Five Dramatistic Pentad strategy for viewing life, not as life itself,[3] by comparing each social unit involved in human activities as five elements of drama – act, scene, agent, agency, and purpose,[4] to answer the empirical question of how persons explain their actions,[2] and to find the ultimate motivations of human activities.

It is possible because Burke believes that Drama has recognizable genres. Humans use language in patterned discourses, and texts move us with recurring patterns underlying those texts.[5] And drama has certain audiences, which means rhetoric plays a crucial role when humans deal with experiences. Language strategies are central to Burke's dramatistic approach.[6]

Assumptions

Because of the complexity and extension of Burke's thinking, it is difficult to label the ontology behind his theory. However, some basic assumptions can still be extracted to support the understanding of dramatism.

- Some of what we do is motivated by animality and some of it by symbolicity.[5] Human's drinking water is to satisfy the thirst, an animal need, and reading paper is influenced by symbols. Burke's position is that both animal nature and symbols motivate us. For him, of all the symbols, language is the most important.

- When we use language, we are used by it as well. Burke held a concept of linguistic relativity similar to the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. Words set our concepts and opinions, which means people cannot see beyond what their words lead them to believe.[7] This assumption suggests that language exerts a determining influence over people,[8] which means meanwhile people's propositions are often restricted to be polarized by language, because some language cannot express much nuance of opinion.

- We are choice makers. Agency (sociology) is another key point of dramatism. "The essence of agency is choice."[9] Social actors have the ability of acting out of choices.

Key Concepts

There are three key concepts associated with dramatism:

1. Dramatistic pentad

The Dramatistic Pentad is an instrument used as a set of relational or functional principles that could help us understand what he calls the ‘cycle cluster of terms’ people use to attribute motive.[1] This pentad is a dissolution to drama.[10] It is parallel with Aristotle’s four causes and has a similar correlation to journalists catchism: who, what, when, where, why, and how.[2] This is done through the five key elements of human drama – act, scene, agent, agency, and purpose.[4]

- Act: What was done

- Scene: Where it was done

- Agent: Who did it

- Agency: How the speaker did it – methods and technologies – message strategies, storytelling, apologies for example.

- Purpose: Why it happened

Any complete statement about motives will offer some kind of answers to these five questions.[10] While it is important to understand each element of the Pentad on its own, it is more important to understand how the elements work together. This is called a ratio, and there are ten possible ratios within the Pentad. Burke maintained that analyzing the ratios of a speaker’s presentation would expose the resources of ambiguity people might exploit to interpret complex problems.[1] The most common ratios used by Burke are Scene-Act and Scene-Agent. When engaged in a dramatistic study, he notes, "the basic unit of action would be defined as 'the human body in conscious or purposive motion'", which is an agent acting in a situation.[2]

- Attitude: How to prepare for an act

In the 1969 edition of Grammar, Burke added a new element, Attitude, thereby making the pentad a hexad.[11] Attitude means "the preparation for an act, which would make it a kind of symbolic act, or incipient act." [12]

The Pentad is a simple tool for seeing and understanding the complexity of a situation. It reveals the nuances and complications of language as symbolic action, which in turn, opens up our perspective.[13]

2. Identification

Identification is the basic function of sociality, using both positive and negative associations. When there is overlap between two people in terms of their substance, they have identification.[14] On the other hand, division is the lack of overlap between two people in matters of essence.[15] According to Burke, identification is an inevitable, thus both beneficial and detrimental characteristic of language in human relations.[16] Identification has the following features:

The chief notion of a "new rhetoric"

Examining Aristotle's principles of rhetoric, Burke points out that the definition of the "old rhetoric" is, in essence, persuasion.[17] Correspondingly, Burke proposes a new rhetoric, which discusses several issues, but mainly focuses on the notion of identification. In comparison with "old" rhetoric, which stresses on deliberate design, "new" rhetoric may include partially "unconscious" factors in its appeal.[18]

Burke's concept of new rhetoric has also been expanded in various academic disciplines. For example, in 2015 philosophers Rutten & Soetaert used the new rhetoric concept to study changing attitudes in regards to education as a way to better understand if Burke's ideas can be applied to this arena.[19]

Burke's new rhetoric has also been used to understand the women's equality movement, specifically in regards to the education of women and sharing of knowledge through print media. Academic Amlong deconstructed print medias of the 1800s addressing human rights as an aspect of educating women about the women's rights movement.[20]

Generated when two people's substances overlap

Burke asserts that all things have substance, which he defines as the general nature of something. Identification is a recognized common ground between two people’s substances, regarding physical characteristics, talents, occupation, experiences, personality, beliefs, and attitudes. The more substance two people share, the greater the identification.[4] It is used to overcome human division.[21]

Can be falsified to result in homophily

Sometimes the speaker tries to falsely identify with the audience, which results in homophily for the audience. Homophily is the perceived similarity between speaker and listener.[4] The so-called "I" is merely a unique combination of potentially conflicting corporate "we's". For example, the use of the people rather than the worker would more clearly tap into the lower middle-class values of the audience the movement was trying to reach.[16]

Reflects ambiguities of substance

Burke recognizes that identification rests on both unity and division, since no one's substance can completely overlap with others. Individuals are "both joined and separated".[17] Humans can unite on certain aspects of substance but at the same time remain unique, which is labeled as "ambiguities". Identification can be increased by the process of consubstantiation, which refers to bridging divisions between two people. Rhetoric is needed in this process to build unity.

3. Guilt

According to Burke, Guilt Redemption is considered the plot of all human drama, or the root of all rhetoric. In this perspective, Burke concluded that the ultimate motivation of man is to purge oneself of one's sense of guilt through public speaking. The term guilt covers tension, anxiety, shame, disgust, embarrassment, and other similar feelings. Guilt serves as a motivating factor that drives the human drama.

Burke's cycle refers to the process of feeling guilt and attempting to reduce it, which follows a predictable pattern: order(or hierarchy), the negative, victimage (scapegoat or mortification), and redemption.

Order or hierarchy

Society is a dramatic process in which hierarchy forms structure through power relationships. The structure of social hierarchy considered in terms of the communication of superiority, inferiority and equality.[22] The hierarchy is created through language using, which enables us to create categories. We feel guilt as a result of our place in the hierarchy.[23]

The negative

The negative comes into play when people see their place in the social order and seek to reject it. Saying no to the existing order is both a function of our language abilities and evidence of humans as choice makers.[22] Burke coined the phrase "rotten with perfection", which means that because our symbols allow us to imagine perfection, we always feel guilty about the difference between the reality and the perfection.[24]

Victimage

Victimage is the process of scapegoating. Here, the speaker blames an external source for his ills.[4] According to Burke, there are two different types of scapegoating, universal and fractional. In universal scapegoating, the speaker blames everyone for the problem, so the audience associates and even feels sorry for the victim, because it includes themselves. In fractional scapegoating, the speaker blames a specific group or a specific person for their problems. This creates a division within the audience.[25] The victim, whoever it may be, is vilified, or made up to violate the ideals of social order, like normalcy or decency. As a result, by people who take action against the villains become heroized because they are confronting evil.[26]

Redemption

This is a confession of guilt by the speaker and a request for forgiveness.[4] Normally, these people are sentenced to a certain punishment so they can reflect and realize their sins. This punishment is specifically a kind of “death,” literal or figuratively.

Many speakers experience a combination of these two guilt-purging options.The ongoing cycle starts with order. The order is the status quo, where everything is right with the world. Then pollution disrupts the order. The pollution is the guilt or sin. Then casuistic stretching allows the guilt to be accepted into the world. Next, is the guilt, which is the effect of the pollution. After that, is victimage or mortification which purges the guilt. Finally comes transcendence which is new order, the now status quo.[4]

Utility

Dennis Brissett and Charles Edgley examine the utility of dramatism on different levels, which can be categorized as the following dimensions:[27]

The dramaturgical self

Dramaturgical perspective is vividly used to analyze human individuality. It views individuality as more a social rather than a psychological phenomenon. The concept of a dramaturgical self was formulated by sociologist Erving Goffman was inspired by the theatre, and also finds roots in relations to Burke's work.[28] Specifically, the concept of dramaturgy ideates life as a metaphorical theater, differentiating from Burke's concept of life as a theater itself.

Some examples of classic research questions on the topic involve how people maximize or minimize the expressiveness, how one stage ideal self, the process of impression-management, etc. For example, Larson and Zemke described the roots of the ideation and patterning of temporal socialization which is drawn from biological rhythms, values and beliefs, work and social commitments, cultural beliefs and engagement in activity.[29]

Motivation and drama

Motives play a crucial role in social interaction between an acting person and his or her validating audience. Within the dramaturgical frame, people are rationalizing. Scholars try to provide a way of understanding how the various identities which comprise the self are constructed. For example, Anderson and Swainson tried to find the answer of whether rape is motivated by sex or by power.[30]

Social relationships as drama

Dramatists also concern the ways in which people both facilitate and interfere with the ongoing behavior of others. The emphasis is on the expressive nature of the social bond. Some topics as role taking, role distance are discussed. For example, by analyzing public address, scholars examine why a speaker selects a certain strategy to identify with audience. For example, Orville Gilbert Brim, Jr. analyzed data to interpret how group structure and role learning influence children's understanding of gender.[31]

Organizational dramas

In addition to focusing on the negotiated nature of social organization, dramaturgy emphasizes the manner in which the social order is expressed through social interaction, how social organization is enacted, featured and dramatized. Typical research topics include corporate realm, business influence on federal policy agenda, even funerals and religious themes. For example, by examining the decision making criteria of Business Angels, Baron and Marksman identified four social skills which contribute to entrepreneurial success: social perception; persuasion and social influence; social adaptability and impression management. They employ dramatism to show how these skills are critical in raising finance.[32]

Political dramas

It is acknowledged that the political process has become more and more a theatrical, image-mongering, dramatic spectacle worthy of a show-business metaphor on a grand scale. Scholars study how dramaturgical materials create essential images by analyzing political advertising and campaigns, stagecraft-like diplomacy, etc. For example, Philip.E.Tetlock tried to answer why presidents became more complex in their thinking after winning the campaign. He found the reason is not presidents' own cognitive adjustment, but a means of impression management.[33]

Other application fields

Dramatism provides us a new way to understand people. Burke's goal is to explain the whole of human experience with symbolic interaction. It is used in a variety of fields.

English

Burke's technical term for drama representative anecdote[12] indicates that the compositionist's adage gives appropriate examples covers the case adequately. Winterowd suggests writers should present ideas dramatistically,not relying on argument and demonstration alone but grounding their abstractions in the concreteness of what being called as representative anecdotes.[34] Representative anecdote means conceptual pivot and is equated with a family of terms: enthymeme, thesis, topic sentence, theme. The representative anecdote, can be either support or conceptual pivot, and in the case of drama is both support and conceptual pivot.[35]

Popular art

Dwight Macdonald and Ernest Van Den Haag views that popular (or "mass"-) culture functions not as Scene, as one might ordinarily expect, but as Agency. "Masscult" itself is the force involved in the Act of brainwashing the public into accepting lower standards of art. This Act is accomplished with the "Sub-Agency" of modern electronic technology, the mass media.[36]

Politics

David Ling uses the pentad to analyze Senator Edward Ted Kenndy's address to the people of Massachusetts.(See Chappaquiddick incident)[37] He regards the events surrounding the death of Miss Kopechne as the scene, Kennedy himself as the agent, Kennady's failure to report the accident in time as act, methods to report as agency, and finds out that the purpose for Kennedy is to fulfill his legal and moral duty.

Another example of dramatism in politics is the use of Burke’s rhetorical interpretations as a tool to understand presentations of terrorism in media. Researchers Gurrionero and Canel highlight the use of Burke’s understanding of motives and identification within the context of the media’s framing of terrorist attacks, saying that the words and symbols used are with specific motives to frame the pentad into the voice that benefits the media and viewers at the expense of the acclaimed terrorists.[38]

Communication

Rempel Denise applies dramatism to explore the social networking site MySpace.[39] She analyzed the architecture of MySpace, the identity presentation of users and the audience reception and finds out that legitimate communication is impossible, and consequently, cannot lead the users to act consubstantially.

Culture

Gregory Clark addressed the pentad to look into the sharing places in the United States.[40] He concluded that tourism sites, which work as the scene in pentad, have the tendency to differentiate American people from other culture and therefore established a sense of national identity in terms of a common culture.

Critiques

The theory has four main critiques: scope, parsimony, utility, and the argument as to the stance of theory itself.

Scope

The theory of Dramatism is criticized for being too broad in scope because it aims to explain how humans interact with each other using symbols, which been described as a general explanation that is almost has no meaning as some critics believe.[15]

Parsimony

Relatedly, some critique that the theory lacks parsimony, meaning it is unclear and too large to be useful.[41]

Utility

Other theorists argue that Dramatism lacks utility because it leaves out topics of gender and culture.[42] Notably, Burke included women in his theory (unlike much of scholarship at the time), but feminist scholars, like Condit, found Burke's concepts inadequate to their critical concerns,[43] by using the generic "man" to represent all people.

Feminist critiques

Feminist scholars also talked about our ability as a society to begin to think in new ways about sex and gender, to extent our language beyond duality to a broad "humanity" and to "human beings".[42] Since "being" is a state in which women simply experience life as freely, consciously, and fully as possible, realizing that this is not only the purpose of life but a genuine place from which change can occur.[44] Condit also went on to criticize Burke for assuming culture as a hegemony, specifically in relation to Burke's application of guilt purging within cultures as necessitating victims.

Later scholars, such as Anne Caroline Crenshaw,[45] went on to note that Burke did identify gender relations in one instance in relation to his arguments on social hierarchies through his analysis of socio-sexual relations present in Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis. However, this author notes that Burke’s work wasn’t a critique and examination of this relationship through dramatism, but rather that the theory of dramatism does give space to make such analyses. Furthermore, scholar Brenda Robinson Hancock used Burke’s dramatism to study women’s movements, specifically with identification as actors.[46] Another scholar, Janet Brown,[47] made use of Burke's pentad in relation to understanding and identifications of feminist literature. Despite these works and incorporation of Dramatism in feminist work, there remains the evidence that Burke did not use or intent his theory to account for gender.

Metaphorical or literal?

Another critique of the theory is to whether the theory exists as a metaphorical or literal theory.

Burke staunchly argued that his theory of dramatism is a literal theory, understanding reality as a literal stage with actors and enactment. However, future theorists, specifically Bernard Brock[48] and Herb Simons,[49] went on to argue dramatism as metaphorical theory claiming that Burke’s idea that all the world's a stage is mere a tool of symbolic interaction that signals life as a drama. Of note, the reasoning for Burke to emphasize his theory as literal relates to the reasons to why others claim it to be metaphorical: the issue lies in the understanding of language’s power as a symbol itself.

Notes

- 1 2 3 Blakesley, David. The Elements of Dramatism. New York: Longman. 2002.

- 1 2 3 4 Overington, M. (1977). Kenneth Burke and the Method of Dramatism. Theory and Society, 4, 131-156.

- ↑ Mangham, I. L., & Overington, M. A. (2005). Dramatism and the theatrical metaphor. Life as theater, A dramaturgical sourcebook (2nd ed.), Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick, NJ, 333-346.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Griffin, Em. (2009). A First Look at Communication Theory. (7th ed.) New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- 1 2 Brummett, B. (1993). Landmark Essays on Kenneth Burke (Vol. 2). Lawrence Erlbaum.

- ↑ Brock, B. L. (1985). Epistemology and ontology in Kenneth Burke's dramatism. Communication Quarterly, 33(2), 94-104.

- ↑ Burke, K. (1965). Permanence and Change. 1954. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill.

- ↑ Melia, T. (1989). Scientism and Dramatism: Some Quasi-Mathematical Motifs in the Work of Kenneth Burke. The Legacy of Kenneth Burke, 55-73.

- ↑ Conrad, C., & Macom, E. A. (1995). Re‐visiting Kenneth Burke: Dramatism/logology and the problem of agency. Southern Journal of Communication, 61(1), 11-28.

- 1 2 Crable, Bryan. (2000). Burke's Perspective on Perspectives: Grounding Dramatism in the Representative Anecdote. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 86, 318-333.

- ↑ Anderson, F. D., & Althouse, M. T. (2010). Five fingers or six? Pentad or hexad. KB Journal, 6(2).

- 1 2 Burke, K., 1897. (1955). A grammar of motives. New York: George Braziller.

- ↑ Fox, Catherine.(2002). Beyond the Tyranny of the Real: Revisiting Burke's Pentad as Research Method for Professional Communication. Technical Communication Quarterly, 11, 365-388.

- ↑ West, T., & Turner, L. (2003). Introducing communication theory: analysis and application with powerweb.

- 1 2 West, R. L.; Turner, L. H. (2010). Introducing communication theory: Analysis and application. Boston: McGraw-Hill. pp. 328–342.

- 1 2 Jordan, J. (2005). Dell Hymes, Kenneth Burke's "identification," and the Birth of sociolinguistics. Rhetoric Review. 24(30, 264-279). doi:10.1207/s15427981rr2403_2

- 1 2 Burke, K. (1950). A rhetoric of motives. New York, 43.

- ↑ Hochmuth, M. (1952). Kenneth burke and the "new rhetoric". Quarterly Journal of Speech, 38(2), 133-144.

- ↑ Rutten, Kris; Soetaert, Ronald. "Attitudes Toward Education: Kenneth Burke and New Rhetoric". Studies in Philosophy and Education. 34 (4): 339–347. doi:10.1007/s11217-014-9432-5.

- ↑ Amlong, Terri A. (2013-04-04). ""Universal Human Rights": The New Rhetoric of the Woman's Rights Movement Conceptualized Within the Una (1853-1855)". American Periodicals: A Journal of History & Criticism. 23 (1): 22–42. doi:10.1353/amp.2013.0006. ISSN 1548-4238.

- ↑ Ahmed, R. (2009). Interface of political opportunism and Islamic extremism in Bangladesh: Rhetorical identification in government response. Communication Studies. 60(1). 82-96. doi:10.1080/10510970802623633

- 1 2 Duncan, H. D. (1968). Communication and social order. Transaction Books.

- ↑ West, R., & Turner, L. Introducing communication theory. 2009.

- ↑ Burke, K. (1966). Language as symbolic action: Essays on life, literature and method. University of California Pr.

- ↑ Moore, M. P. (2006). To Execute Capital Punishment: The Mortification and Scapegoating of Illinois Governor George Ryan. Western Journal of Communication, 70(4), 311-330. doi:10.1080/10570310600992129

- ↑ Blain, M. (2005). The politics of victimage:. Critical Discourse Studies, 2(1), 31-50. doi:10.1080/17405900500052168

- ↑ Brissett, D., & Edgley, C. (Eds.). (2005). Life as theater: A dramaturgical sourcebook. Transaction Books.

- ↑ Goffman, Erving (1969). The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Allen Lane.

- ↑ Larson, E. A., & Zemke, R. (2003). Shaping the Temporal Patterns of our Lives: The Social Coordination of. Journal of Occupational Science, 10(2), 80-89.

- ↑ Anderson, I., & Swainson, V. (2001). Perceived motivation for rape: Gender differences in beliefs about female and male rape. Current Research in Social Psychology, 6(8), 107-122.

- ↑ Brim, O. G. (1958). Family structure and sex role learning by children: A further analysis of Helen Koch's data. Sociometry, 21(1), 1-16.

- ↑ Baron, R. A., & Markman, G. D. (2000). Beyond social capital: How social skills can enhance entrepreneurs' success. The Academy of Management Executive, 14(1), 106-116.

- ↑ Philip E. Tetlock (1981).Pre- to Postelection Shifts in Presidential Rhetoric: Impression Management or Cognitive Adjustment? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol 41(2), 207-212.

- ↑ Anderson, C. (1985). Dramatism and Deliberation. Rhetoric Review, 4(1), 34-43.

- ↑ Winterowd, W. R. (1983). Dramatism in themes and poems. College English, 45(6), 581-588.

- ↑ Kimberling, C. R. (1982). Kenneth Burke's dramatism and popular arts. Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green State University Popular Press

- ↑ David A. Ling (1969). A pentadic analysis of senator Edward Kennedy's address to the people of Massachusetts. Communication Studies, 21(2), 81-86

- ↑ Canel, María José; Gurrionero, Mario García. "Framing analysis, dramatism and terrorism coverage: politician and press responses to the Madrid airport bombing". Communication & Society. 29 (4): 133–149. doi:10.15581/003.29.4.133-149.

- ↑ Rempel, D. (2008). An exploration of the social networking site MySpace using kenneth burke's theory of dramatism

- ↑ Clark,G., & Benson, T. W. (2004). Rhetorical Landscapes in America: Variations on a Theme from Kenneth Burke. Columbia, SC: U of South Carolina P.

- ↑ Foss, Karen A.; Trapp, Robert (1991-01-01). Contemporary Perspectives on Rhetoric. Waveland Press. ISBN 9780881335422.

- 1 2 Condit, C. M. (1992). Post-Burke: Transcending the Sub-Stance of Dramatism. The Quarterly Journal of Speech, 78(3), 349-355.

- ↑ Japp, P. M. (1999). 'Can This Marriage Be Saved?': Reclaiming Burke for Feminist Scholarship. In B. i. Brock (Ed.) , Kenneth Burke and the 21st Century (pp. 113-130). Albany, NY: State U of New York P.

- ↑ Foss, K. A., & White, C. L. (1999). 'Being' and the Promise of Trinity: A Feminist Addition to Burke's Theory of Dramatism. In B. i. Brock (Ed.) , Kenneth Burke and the 21st Century (pp. 99-111). Albany, NY: State U of New York P.

- ↑ Crenshaw, Anne Caroline (1992). "The Rhetoric of Fetal Protection Policies: Toward a Feminist Dramatism". niversity of Southern California.

- ↑ Hancock, Brenda Robinson (1972-10-01). "Affirmation by negation in the women's liberation movement". Quarterly Journal of Speech. 58 (3): 264–271. doi:10.1080/00335637209383123. ISSN 0033-5630.

- ↑ Brown, Janet (1979). "Kenneth Burke and the Mod Donna: The Dramatistic Method Applied to Feminist Criticism". Central States Speech Journa. 30: 250–61.

- ↑ Brock, Bernard L. (1985-03-01). "Epistemology and ontology in Kenneth Burke's dramatism". Communication Quarterly. 33 (2): 94–104. doi:10.1080/01463378509369585. ISSN 0146-3373.

- ↑ "Revisiting the Controversy over Dramatism as Literal | KB Journal". www.kbjournal.org. Retrieved 2017-11-16.

References

- Ahmed, R. (2009). Interface of political opportunism and Islamic extremism in Bangladesh: Rhetorical identification in government response. Communication Studies. 60(1). 82-96. doi:10.1080/10510970802623633

- Benoit, William L. (1983). Systems of Explanation: Aristotle and Burke on Cause. Rhetoric Society Quarterly, 13, 41-57.

- Blakesley, David. The Elements of Dramatism. New York: Longman. 2002

- Brock, Bernard L.; Burke, Kenneth; Burgess, Parke G.; Simons, Herbert W. (1985). Dramatism as Ontology or Epistemology: A Symposium. Communication Quarterly, 33, 17-33.

- Burke, Kenneth. Kenneth Burke on Shakespeare. Parlor Press, 2007.

- Burke, Kenneth. (1978). "Questions and Answers about the Pentad" College Composition and Communication, 29(4), 330-335.

- Crable, Bryan. (2000). Burke's Perspective on Perspectives: Grounding Dramatism in the Representative Anecdote. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 86, 318-333.

- Crable, B. (2000). Defending dramatism as ontological and literal. Communication Quarterly. 48(4), 323-342

- Fox, Catherine.(2002). Beyond the Tyranny of the Real: Revisiting Burke's Pentad as Research Method for Professional Communication. Technical Communication Quarterly, 11, 365-388.

- Griffin, Em. (2006). A First Look at Communication Theory. (6th ed.) New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Hamlin, William J.; Nichols, Harold J. (1973). The Interest Value of Rhetorical Strategies Derived from Kenneth Burke's Pentad. Western Speech, 37, 97-102.

- Jordan, J. (2005). Dell Hymes, Kenneth Burke’s “identification,” and the Birt of sociolinguistics. Rhetoric Review. 24(30, 264-279. doi:10.1207/s15427981rr2403_2

- Manning, Peter K. (1999). High Risk Narratives: Textual Adventures. Qualitative Sociology, 22, 285-299.

- Miller, K. (2005). Communication theories: perspectives, processes, and contexts.(2nd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Overington, M. (1977). Kenneth Burke and the Method of Dramatism. Theory and Society, 4, 131-156.

- Rountree, C. (2010). Revisiting the Controversy over Dramatism as Literal. The Journal of the Kenneth Burke Society, 6(2). Retrieved from http://www.kbjournal.org/content/revisiting-controversy-over-dramatism-literal

- West, R. L., & Turner, L. H. (2010). Introducing communication theory: Analysis and application. Boston: McGraw-Hill.

- Kimberling, C. (1982). Kenneth Burke’s dramatism and popular arts. Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green State University Popular Press

- Burke, K. (n.d.). Dramatism and logology. Communication Quarterly, 33(2), 89–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463378509369584