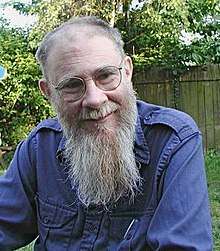

David Lewis (philosopher)

| David Lewis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

David Kellogg Lewis September 28, 1941 Oberlin, Ohio |

| Died |

October 14, 2001 (aged 60) Princeton, New Jersey |

| Alma mater |

Swarthmore College Oxford University Harvard University |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School |

Analytic Nominalism[1] Perdurantism[2] |

| Doctoral advisor | Willard Van Orman Quine |

| Other academic advisors | Donald Cary Williams[3] |

| Doctoral students |

Robert Brandom J. David Velleman |

Main interests |

Logic · Language · Metaphysics Epistemology · Ethics |

Notable ideas |

Possible worlds · Modal realism · Counterfactuals · Counterpart theory · Principal principle · Humean supervenience · Lewis signaling game · The endurantism–perdurantism distinction Descriptive-causal theory of reference[4] · De se |

David Kellogg Lewis (September 28, 1941 – October 14, 2001) was an American philosopher. Lewis taught briefly at UCLA and then at Princeton from 1970 until his death. He is also closely associated with Australia, whose philosophical community he visited almost annually for more than thirty years. He made contributions in philosophy of language, philosophy of mind, philosophy of probability, metaphysics, epistemology, philosophical logic, and aesthetics. He is probably best known for his controversial modal realist stance: that (i) possible worlds exist, (ii) every possible world is a concrete entity, (iii) any possible world is causally and spatiotemporally isolated from any other possible world, and (iv) our world is among the possible worlds.

Early life and education

Lewis was born in Oberlin, Ohio, to John D. Lewis, a Professor of Government at Oberlin College, and Ruth Ewart Kelloggs Lewis, a distinguished medieval historian. The formidable intellect for which he was known later in his life was already manifest during his years at Oberlin High School, when he attended college lectures in chemistry. He went on to Swarthmore College and spent a year at Oxford University (1959–1960), where he was tutored by Iris Murdoch and attended lectures by Gilbert Ryle, H.P. Grice, P.F. Strawson, and J.L. Austin. It was his year at Oxford that played a seminal role in his decision to study philosophy, and which made him the quintessentially analytic philosopher that he would soon become. Lewis went on to receive his Ph.D from Harvard in 1967, where he studied under W.V.O. Quine, many of whose views he came to repudiate. It was there that his connection with Australia was first established when he took a seminar with J.J.C. Smart, a leading Australian philosopher. "I taught David Lewis," Smart would say in later years, "Or rather, he taught me."

Early work on convention

Lewis's first monograph was Convention: A Philosophical Study (1969), which is based on his doctoral dissertation and uses concepts of game theory to analyze the nature of social conventions; it won the American Philosophical Association's first Franklin Matchette Prize for the best book published in philosophy by a philosopher under 40 years old. Lewis claimed that social conventions, such as the convention in most states that one drives on the right (not on the left), the convention that the original caller will re-call if a phone conversation is interrupted, etc., are solutions to so-called "'co-ordination problems'". Co-ordination problems were at the time of Lewis's book an under-discussed kind of game-theoretical problem; most of the game-theoretical discussion had circulated around problems where the participants are in conflict, such as the prisoner's dilemma.

Co-ordination problems are problematic, for, though the participants have common interests, there are several solutions. Sometimes, one of the solutions may be "'salient'", a concept invented by the game-theorist and economist Thomas Schelling (by whom Lewis was much inspired). For example, a co-ordination problem that has the form of a meeting may have a salient solution if there is only one possible spot to meet in town. But in most cases, we must rely on what Lewis calls "precedent" in order to get a salient solution. If both participants know that a particular co-ordination problem, say "which side should we drive on?" has been solved in the same way numerous times before, both know that both know this, both know that both know that both know this, etc. (this particular state Lewis calls common knowledge, and it has since been much discussed by philosophers and game theorists), then they will easily solve the problem. That they have solved the problem successfully will be seen by even more people, and thus the convention will spread in the society. A convention is thus a behavioural regularity that sustains itself because it serves the interests of everyone involved. Another important feature of a convention is that a convention could be entirely different: one could just as well drive on the left; it is more or less arbitrary that one drives on the right in the USA, for example.

Lewis's main goal in the book, however, wasn't simply to provide an account of convention but rather to investigate the "platitude that language is ruled by convention" (Convention, p. 1.) The last two chapters of the book (Signalling Systems and Conventions of Language; cf. also "Languages and Language", 1975) make the case that the use of a language in a population consists of conventions of truthfulness and trust among members of the population. Lewis recasts in this framework notions as those of truth and analyticity, claiming that they are better understood as relations between sentences and a language, rather than as properties of sentences.

Counterfactuals and modal realism

Lewis went on to publish Counterfactuals (1973), which contained an analysis of counterfactual conditionals in terms of the theory of possible worlds. According to Lewis, what makes a statement of the form

"Had I made that shot our team would have won the game."

true is that in any world where I make the shot but the world is otherwise as similar as possible to the actual one, our team wins the game. If there is a world maximally similar to ours where I make the shot but our team still loses, the counterfactual is false. This treatment of counterfactuals is a variation or generalization of the one published by Robert Stalnaker a few years earlier, and consequently this kind of treatment is called the Stalnaker-Lewis theory.

Realism about possible worlds

What made Lewis's views about counterfactuals controversial is that whereas Stalnaker treated possible worlds as imaginary entities, "made up" for the sake of theoretical convenience, Lewis adopted a position his formal account of counterfactuals did not commit him to, namely modal realism. According to this view as Lewis formulated it, when we speak of a world where I made the shot that in this world I missed, we are speaking of a world just as real as this one, and although we say that in that world I made the shot, more precisely it is not I but a counterpart of mine that was successful.

He had already proposed this view in some of his earlier papers: "Counterpart Theory and Quantified Modal Logic" (1968), "Anselm and Actuality" (1970), and "Counterparts of Persons and their Bodies" (1971). The theory was widely considered implausible, but Lewis urged that it should be taken seriously. Most often the idea that there exists an infinite number of causally isolated universes, each as real as our own but different from it in some way, and that furthermore that alluding to objects in this universe as necessary in order to explain what makes certain counterfactual statements true but not others, meets with what Lewis calls the "incredulous stare" (Lewis, OPW, 2005, pg. 135-137). Lewis defends and elaborates his theory of extreme modal realism, while insisting that there is nothing extreme about it, in On the Plurality of Worlds (1986). Lewis acknowledges that his theory is contrary to common sense, but believes that its advantages far outweigh this disadvantage, and that therefore we should not be hesitant to pay this price.

According to Lewis, "actual" is merely an indexical label we give to a world when we locate ourselves in it. Things are necessarily true when they are true in all possible worlds. (Note that Lewis is not the first one to speak of possible worlds in this context. Leibniz and C.I. Lewis, for example, both speak of possible worlds as a way of thinking about possibility and necessity, and some of David Kaplan's early work is on the counterpart theory. Lewis's original suggestion was that all possible worlds are equally concrete, and the world in which we find ourselves is no more real than any other possible world.)

Criticisms

This theory has faced a number of criticisms. In particular, it is not clear how we could know what goes on in other worlds. After all, they are causally disconnected from ours; we can't look into them to see what is going on there.[6] A related objection is that, while people are concerned with what they could have done, they are not concerned with what some people in other worlds, no matter how similar to them, do. As Saul Kripke once put it, a presidential candidate could not care less whether someone else, in another world, wins an election, but does care whether he himself could have won it (Kripke 1980, p. 45). A more basic criticism is that introducing so many entities into our ontology violates the maxim of Occam's razor, which tells us not to multiply theoretical entities beyond what is necessary to explain the facts our theories aim to explain.

Possible worlds are employed in the work of Saul Kripke[7] and many others, but not in the concrete sense propounded by Lewis. While none of these alternative approaches has found anything near universal acceptance, very few philosophers accept Lewis's particular brand of modal realism.

Influence

At Princeton, Lewis was a mentor of young philosophers, and trained dozens of successful figures in the field, including several current Princeton faculty members, as well as people now teaching at a number of the leading philosophy departments in the U.S. Among his most prominent students are Bob Brandom at the University of Pittsburgh, L.A. Paul at the University of North Carolina, Cian Dorr and David Velleman at NYU, Peter Railton at Michigan, and Joshua Greene at Harvard. His direct and indirect influence is evident in the work of many prominent philosophers of the current generation.

Later life and death

Lewis suffered from severe diabetes for much of his life, which eventually grew worse and led to kidney failure. In July 2000 he received a kidney transplant from his wife Stephanie. The transplant allowed him to work and travel for another year, before he died suddenly and unexpectedly from further complications of his diabetes, on October 14, 2001.[8]

Since his death a number of posthumous papers have been published, on topics ranging from truth and causation to philosophy of physics. Lewisian Themes, a collection of papers on his philosophy, was published in 2004.

Works

Books

- Convention: A Philosophical Study, Harvard University Press 1969.

- Counterfactuals, Harvard University Press 1973; revised printing Blackwell 1986.

- Semantic Analysis: Essays Dedicated to Stig Kanger on His Fiftieth Birthday, Reidel 1974.

- On the Plurality of Worlds, Blackwell 1986.

- Parts of Classes, Blackwell 1991.

Lewis published five volumes containing 99 papers — almost all of the papers he published during his lifetime. These papers discuss his counterfactual theory of causation, the concept of semantic score, a contextualist analysis of knowledge, a dispositional value theory, among many other topics.

- Philosophical Papers, Vol. I (1983) includes his early work on counterpart theory, and the philosophy of language and of mind.

- Philosophical Papers, Vol. II (1986) includes his work on counterfactuals, causation, and decision theory, where he promotes his principal principle[9] about rational belief. Its preface discusses Humean supervenience, the name Lewis gave to his overarching philosophical project.

- Papers in Philosophical Logic (1998).

- Papers in Metaphysics and Epistemology (1999) contains "Elusive Knowledge" and "Naming the Colours," honored by being reprinted in the Philosopher's Annual for the year they were first published.

- Papers in Ethics and Social Philosophy (2000).

Lewis's monograph, Parts of Classes (1991), on the foundations of mathematics, sketched a reduction of set theory and Peano arithmetic to mereology and plural quantification. Very soon after its publication, Lewis became dissatisfied with some aspects of its argument; it is currently out of print (his paper "Mathematics is megethology," in "Papers in Philosophical Logic," is partly a summary and partly a revision of "Parts of Classes").

Selected papers

- "Counterpart Theory and Quantified Modal Logic." Journal of Philosophy 65 (1968): pp. 113–126.

- "General semantics." Synthese, 22(1) (1970): pp. 18–67.

- "The Paradoxes of Time Travel", American Philosophical Quarterly, April (1976): pp. 145–152.

- "Truth in Fiction." American Philosophical Quarterly 15 (1978): pp. 37–46.

- "How to Define Theoretical Terms." Journal of Philosophy 67 (1979): pp. 427–46.

- "Scorekeeping in a Language Game." Journal of Philosophical Logic 8 (1979): pp. 339–59.

- "Mad pain and Martian pain." Readings in the Philosophy of Psychology Vol. I. N. Block, ed. Harvard University Press (1980): pp. 216–222.

- "Are We Free to Break the Laws?" Theoria 47 (1981): pp. 113–21.

- "New Work for a Theory of Universals." Australasian Journal of Philosophy 61 (1983): pp. 343–77.

- "What Experience Teaches." in Mind and Cognition by William G. Lycan, (1990 Ed.) pp. 499–519. Article omitted from subsequent editions.

- "Elusive Knowledge", Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 74/4 (1996): pp. 549–567.

See also

References

- ↑ "Review of Gonzalo Rodriguez-Pereyra, Resemblance Nominalism: A Solution to the Problem of Universals" – ndpr.nd.edu

- ↑ Lewis, D. K. 1986. On the Plurality of Worlds Oxford: Blackwell.

- ↑ Wolterstorff, Nicholas (November 2007). "A Life in Philosophy". Proceedings and Addresses of the American Philosophical Association. 81 (2). JSTOR 27653995.

- ↑ Stefano Gattei, Thomas Kuhn's 'Linguistic Turn' and the Legacy of Logical Empiricism: Incommensurability, Rationality and the Search for Truth, Ashgate Publishing, 2012, p. 122 n. 232.

- ↑ Stathis Psillos, Scientific Realism: How Science Tracks Truth, Routledge, 1999, p. xxiii.

- ↑ Stalnaker, Inquiry, p. 49: "But if other possible worlds are causally disconnected from us, how do we know anything about them?"

- ↑ "Naming and Necessity", In Semantics of Natural Language, edited by D. Davidson and G. Harman. 1980 (1972) Dordrecht; Boston: Reidel.

- ↑ "David Kellogg Lewis". The New York Times. October 20, 2001.

David Kellogg Lewis, a metaphysician and a philosopher of mind, language and logic at Princeton University, died on Sunday at his home in Princeton, N.J. He was 60. The cause was heart failure, Princeton University said. Mr. Lewis was once dubbed a mad-dog modal realist for his idea that any logically possible world you can think of actually exists. He believed, for instance, that there was a world with talking donkeys.

- ↑ A Subjectivist's Guide to Objective Chance, Philosophical Papers of David Lewis, Volume 2, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986, pp. 83–132.

External links

- Weatherson, Brian. "David Lewis". In Zalta, Edward N. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Hall, Ned. "David Lewis's Metaphysics". In Zalta, Edward N. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Service of Remembrance Friday, February 8, 2002 - Princeton University Chapel at the Wayback Machine (archived October 3, 2003)

- Photos from the weekend of the memorial service for David Lewis in Princeton, February 2002