Dermacentor variabilis

| Dermacentor variabilis | |

|---|---|

| |

| female | |

| |

| male | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Arachnida |

| Subclass: | Acari |

| Superorder: | Parasitiformes |

| Order: | Ixodida |

| Family: | Ixodidae |

| Genus: | Dermacentor |

| Species: | D. variabilis |

| Binomial name | |

| Dermacentor variabilis (Say, 1821) | |

| |

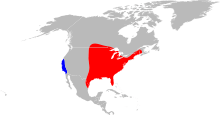

| Normal range in red; other reports in blue | |

.jpg)

Dermacentor variabilis, also known as the American dog tick or wood tick, is a species of tick that is known to carry bacteria responsible for several diseases in humans, including Rocky Mountain spotted fever and tularemia (Francisella tularensis). It is one of the most well-known hard ticks. Diseases are spread when it sucks blood from the host, which could take several days for the host to experience some symptoms.

Though D. variabilis may be exposed to Borrelia burgdorferi, the causative agent of Lyme disease,[1] these ticks are not competent vectors for the transmission of this disease.[2][3][4] The primary vectors for Borrelia burgdorferi are the deer tick Ixodes scapularis in Eastern parts of the United States, Ixodes pacificus in California and Oregon, and Ixodes ricinus in Europe. Dermacentor variabilis may also carry Anaplasma phagocytophilum, the causative agent of HGA (Human granulocytic anaplasmosis), and Ehrlichia chaffeensis, the causative agent of HME (human monocytic ehrlichiosis).[1]

Dermacentor ticks may also induce tick paralysis by elaboration of a neurotoxin that induces rapidly progressive flaccid quadriparesis similar to Guillain–Barré syndrome. The neurotoxin prevents presynaptic release of acetylcholine from neuromuscular junctions.

The American dog tick is a rather colorful tick and is commonly found in highly wooded, shrubby, and long grass areas. Tick numbers can be reduced in your own back yard by cutting the grass, which creates a low humidity environment which is undesired by ticks. Pesticides can also be used and are most effective when they are applied to vegetation that has been cut to a short level.[5]

Life cycle

The life cycle of ticks can vary depending on the species. The growth stages of a tick start off as an egg, larva (six-legged), nymph, and finally the adult. The adult female tick lays uninfected eggs. The eggs hatch uninfected larva. These larva commonly feed on mammals such as squirrels, humans, deer, mice, raccoons, and even skunks. They also feed on birds. The nymph continues to feed off of the mammals stated above before maturing into an infected adult. Once the tick reaches the adult stage, it will commonly feed on larger animals such as the opossum, cat, dog, deer, and humans.[6]

Disease transmission

Symptoms of Rocky Mountain spotted fever can first be noted by the appearance of a rash around the wrists and ankles that moves slowly up to the rest of the body and develops within 2–5 days. Symptoms of tularemia usually appear within 3–5 days, but can appear as late as 21 days after transmission. Oftentimes patients will experience chills, swollen lymph nodes, and an ulceration at the site of the bite.[5]

A tick bite does not automatically transfer diseases to the host. Instead, the tick needs to be attached to the host for a period of time, generally 6–8 hours, before it is capable of transferring disease.[5] However, the required tick attachment period is as brief as 2 hours for the transmission of Rickettsia rickettsii, the bacterium responsible for Rocky Mountain spotted fever. This gives the host an opportunity to remove this parasite before disease transmission occurs.

See also

- Rhipicephalus sanguineus (Latreille, 1806) – brown dog tick

- Ticks of domestic animals

Bibliography

- Piesman J, Sinsky RJ (September 1988). "Ability to Ixodes scapularis, Dermacentor variabilis, and Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae) to acquire, maintain, and transmit Lyme disease spirochetes (Borrelia burgdorferi)". J. Med. Entomol. 25 (5): 336–9. doi:10.1093/jmedent/25.5.336. PMID 3193425.

References

- 1 2 Kevin Holden; John T. Boothby; Sulekha Anand & Robert F. Massung (2003). "Detection of Borrelia burgdorferi, Ehrlichia chaffeensis, and Anaplasma phagocytophilum in Ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) from a Coastal Region of California". J. Med. Entomol. 40 (4): 534–9. doi:10.1603/0022-2585-40.4.534. PMID 14680123.

- ↑ Joseph Piesman & Christine M. Happ (1997). "Ability of the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi to infect rodents and three species of human-biting ticks (blacklegged tick, American dog tick, lone star tick) (Acari:Ixodidae)". J. Med. Entomol. 34 (4): 451–6. doi:10.1093/jmedent/34.4.451. PMID 9220680.

- ↑ F. H. Sanders & J. H. Oliver (1995). "Evaluation of Ixodes scapularis, Amblyomma americanum, and Dermacentor variabilis (Acari: Ixodidae) from Georgia as vectors of a Florida strain of the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi". J. Med. Entomol. 32 (4): 402–426. doi:10.1093/jmedent/32.4.402. PMID 7650697.

- ↑ Stanley W. Mukolwe; A. Alan Kocan; Robert W. Barker; Katherine M. Kocan & George L. Murphy (1992). "Attempted transmission of Borrelia burgdorferi (Spirochaetales: Spirochaetaceae) (JDI strain) by Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae), Dermacentor variabilis, and Amblyomma americanum". J. Med. Entomol. 29 (4): 673–7. doi:10.1093/jmedent/29.4.673. PMID 1495078.

- 1 2 3 "American dog tick - Dermacentor variabilis (Say)". entnemdept.ufl.edu. Retrieved 2016-05-05.

- ↑ "Dermacentor variabilis". Wisconsin Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases. 2012-02-16. Retrieved 2016-05-04.

External links

- Ohio State University Extension Fact Sheet

- Illinois photographs

- Iowa tick images

- American dog tick on the University of Florida / Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences Featured Creatures website