Acute radiation syndrome

| Acute radiation syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Synonyms | Radiation poisoning, radiation sickness, radiation toxicity |

| |

| Radiation causes cellular degradation by autophagy. | |

| Specialty | Toxicology |

Acute radiation syndrome (ARS) is a collection of health effects that are present within 24 hours of exposure to high doses of ionizing radiation. It is also called radiation poisoning, radiation sickness and radiation toxicity.

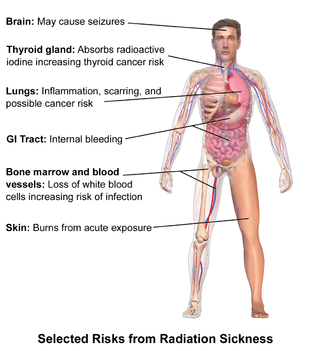

The onset and type of symptoms depends on the amount of radiation exposure, both in any one dose, and cumulative exposure. Relatively smaller doses result in gastrointestinal effects, such as nausea and vomiting, and symptoms related to falling blood counts, and predisposition to infection and bleeding. Relatively larger doses can result in neurological effects, including but not limited to seizures, tremors, lethargy, and rapid death.[1] Treatment of acute radiation syndrome is generally supportive with blood transfusions and antibiotics, with some extreme cases requiring more aggressive treatments, such as bone marrow transfusions.[2]

The radiation causes cellular degradation due to damage to DNA and other key molecular structures within the cells in various tissues. This destruction, particularly because it affects the ability of cells to divide normally, in turn causes the symptoms. The symptoms can begin within one or two hours and may last for several months.[2][3] The terms refer to acute medical problems rather than ones that develop after a prolonged period.[4][5][6]

Similar symptoms may appear months to years after exposure as chronic radiation syndrome when the dose rate is too low to cause the acute form.[7] Radiation exposure can also increase the probability of developing some other diseases, mainly different types of cancers.[8] These later-developing diseases are sometimes also described as radiation sickness, but they are never included in the term acute radiation syndrome.[9]

Signs and symptoms

Classically acute radiation syndrome is divided into three main presentations: hematopoietic, gastrointestinal, and neurological/vascular. These syndromes may or may not be preceded by a prodrome.[2] The speed of onset of symptoms is related to radiation exposure, with greater doses resulting in a shorter delay in symptom onset.[2] These presentations presume whole-body exposure and many of them are markers which are not valid if the entire body has not been exposed. Each syndrome requires that the tissue showing the syndrome itself be exposed. The hematopoietic syndrome requires exposure of the areas of bone marrow actively forming blood elements (i.e., the pelvis and sternum in adults). The neurovascular symptoms require exposure of the brain. The gastrointestinal syndrome is not seen if the stomach and intestines are not exposed to radiation. Some areas affected are:

- Hematopoietic. This syndrome is marked by a drop in the number of blood cells, called aplastic anemia. This may result in infections due to a low amount of white blood cells, bleeding due to a lack of platelets, and anemia due to too few red blood cells in the circulation.[2] These changes can be detected by blood tests after receiving a whole-body acute dose as low as 0.25 grays (25 rad), though they might never be felt by the patient if the dose is below 1 gray (100 rad). Conventional trauma and burns resulting from a bomb blast are complicated by the poor wound healing caused by hematopoietic syndrome, increasing mortality.

- Gastrointestinal. This syndrome often follows absorbed doses of 6–30 grays (600–3,000 rad).[2] The signs and symptoms of this form of radiation injury include nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, and abdominal pain.[10] Vomiting in this time-frame is a marker for whole body exposures that are in the fatal range above 4 grays (400 rad). Without exotic treatment such as bone marrow transplant, death with this dose is common.[2] The death is generally more due to infection than gastrointestinal dysfunction.

- Neurovascular. This syndrome typically occurs at absorbed doses greater than 30 grays (3,000 rad), though it may occur at 10 grays (1,000 rad).[2] It presents with neurological symptoms such as dizziness, headache, or decreased level of consciousness, occurring within minutes to a few hours, and with an absence of vomiting. It is invariably fatal.[2]

The prodrome (early symptoms) of ARS typically includes nausea and vomiting, headaches, fatigue, fever, and a short period of skin reddening.[2] These symptoms may occur at radiation doses as low as 0.35 grays (35 rad). These symptoms are common to many illnesses, and may not, by themselves, indicate acute radiation sickness.[2]

Whole-body absorbed dose effect

| Phase | Symptom | Whole-body absorbed dose (Gy) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–2 Gy | 2–6 Gy | 6–8 Gy | 8–30 Gy | > 30 Gy | ||

| Immediate | Nausea and vomiting | 5–50% | 50–100% | 75–100% | 90–100% | 100% |

| Time of onset | 2–6 h | 1–2 h | 10–60 min | < 10 min | Minutes | |

| Duration | < 24 h | 24–48 h | < 48 h | < 48 h | N/A (patients die in < 48 h) | |

| Diarrhea | None | None to mild (< 10%) | Heavy (> 10%) | Heavy (> 95%) | Heavy (100%) | |

| Time of onset | — | 3–8 h | 1–3 h | < 1 h | < 1 h | |

| Headache | Slight | Mild to moderate (50%) | Moderate (80%) | Severe (80–90%) | Severe (100%) | |

| Time of onset | — | 4–24 h | 3–4 h | 1–2 h | < 1 h | |

| Fever | None | Moderate increase (10–100%) | Moderate to severe (100%) | Severe (100%) | Severe (100%) | |

| Time of onset | — | 1–3 h | < 1 h | < 1 h | < 1 h | |

| CNS function | No impairment | Cognitive impairment 6–20 h | Cognitive impairment > 24 h | Rapid incapacitation | Seizures, tremor, ataxia, lethargy | |

| Latent period | 28–31 days | 7–28 days | < 7 days | None | None | |

| Symptom | Mild to moderate Leukopenia Fatigue Weakness |

Moderate to severe Leukopenia Purpura Hemorrhage Infections Alopecia after 3 Gy |

Severe leukopenia High fever Diarrhea Vomiting Dizziness and disorientation Hypotension Electrolyte disturbance |

Nausea Vomiting Severe diarrhea High fever Electrolyte disturbance Shock |

N/A (patients die in < 48h) | |

| Mortality | Without care | 0–5% | 5–95% | 95–100% | 100% | 100% |

| With care | 0–5% | 5–50% | 50–100% | 99–100% | 100% | |

| Death | 6–8 weeks | 4–6 weeks | 2–4 weeks | 2 days – 2 weeks | 1–2 days | |

| Table Source[1] | ||||||

Skin changes

Cutaneous radiation syndrome (CRS) refers to the skin symptoms of radiation exposure.[6] Within a few hours after irradiation, a transient and inconsistent redness (associated with itching) can occur. Then, a latent phase may occur and last from a few days up to several weeks, when intense reddening, blistering, and ulceration of the irradiated site are visible. In most cases, healing occurs by regenerative means; however, very large skin doses can cause permanent hair loss, damaged sebaceous and sweat glands, atrophy, fibrosis (mostly Keloids), decreased or increased skin pigmentation, and ulceration or necrosis of the exposed tissue.[6] Notably, as seen at Chernobyl, when skin is irradiated with high energy beta particles, moist desquamation (peeling of skin) and similar early effects can heal, only to be followed by the collapse of the dermal vascular system after two months, resulting in the loss of the full thickness of the exposed skin.[11] This effect had been demonstrated previously with pig skin using high energy beta sources at the Churchill Hospital Research Institute, in Oxford.[12]

Cancer

According to the linear no-threshold model, any exposure to ionizing radiation, even at doses too low to produce any symptoms of radiation sickness, can induce cancer due to cellular and genetic damage. Under the assumption, survivors of acute radiation syndrome face an increased risk of developing cancer later in life. The probability of developing cancer is a linear function with respect to the effective radiation dose. In radiation-induced cancer, the speed at which the condition advances, the prognosis, the degree of pain, and every other feature of the disease are not believed to be functions of the radiation dosage.

However, some studies contradict the linear no-threshold model. These studies indicate that some low levels of radiation do not increase cancer risk at all, and that there may exist a threshold dosage of ionizing radiation below which exposure should be considered safe. Nonetheless the 'no safe amount' assumption is the basis of US and most national regulatory policies regarding "man-made" sources of radiation.

Cause

Radiation sickness is caused by exposure to a large dose of ionizing radiation (> ~0.1 Gy) over a short period of time. (> ~0.1 Gy/h) This might be the result of a nuclear explosion, a criticality accident, a radiotherapy accident as in Therac-25, a solar flare during interplanetary travel, misplacement of radioactive waste as in the 1987 Goiânia accident, human error in a nuclear reactor, or other possibilities. Acute radiation sickness due to ingestion of radioactive material is possible, but rare; examples include the 1987 contamination of Leide das Neves Ferreira and the 2006 poisoning of Alexander Litvinenko.

Alpha and beta radiation have low penetrating power and are unlikely to affect vital internal organs from outside the body. Any type of ionizing radiation can cause burns, but alpha and beta radiation can only do so if radioactive contamination or nuclear fallout is deposited on the individual's skin or clothing. Gamma and neutron radiation can travel much further distances and penetrate the body easily, so whole-body irradiation generally causes ARS before skin effects are evident. Local gamma irradiation can cause skin effects without any sickness. In the early twentieth century, radiographers would commonly calibrate their machines by irradiating their own hands and measuring the time to onset of erythema.[17]

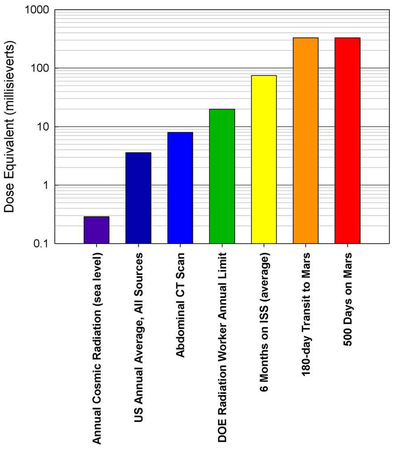

Spaceflight

During spaceflight, particularly flights beyond low Earth orbit, astronauts are exposed to both galactic cosmic radiation (GCR) and solar particle event (SPE) radiation. Evidence indicates past SPE radiation levels which would have been lethal for unprotected astronauts.[18] GCR levels which might lead to acute radiation poisoning are less well understood.[19]

Pathophysiology

The most commonly used predictor of acute radiation symptoms is the whole-body absorbed dose. Several related quantities, such as the equivalent dose, effective dose, and committed dose, are used to gauge long-term stochastic biological effects such as cancer incidence, but they are not designed to evaluate acute radiation syndrome.[20] To help avoid confusion between these quantities, absorbed dose is measured in units of grays (in SI, unit symbol Gy) or rads (in CGS), while the others are measured in sieverts (in SI, unit symbol Sv) or rems (in CGS). 1 rad = 0.01 Gy and 1 rem = 0.01 Sv.[21]

In most of the acute exposure scenarios that lead to radiation sickness, the bulk of the radiation is external whole-body gamma, in which case the absorbed, equivalent and effective doses are all equal. There are exceptions, such as the Therac-25 accidents and the 1958 Cecil Kelley criticality accident, where the absorbed doses in Gy or rad are the only useful quantities.

Radiotherapy treatments are typically prescribed in terms of the local absorbed dose, which might be 60 Gy or higher. The dose is fractionated (about 2 Gy per day for curative treatment), which allows for the normal tissues to undergo repair, allowing it to tolerate a higher dose than would otherwise be expected. The dose to the targeted tissue mass must be averaged over the entire body mass, most of which receives negligible radiation, to arrive at a whole-body absorbed dose that can be compared to the table above.

DNA damage

High radiation doses can cause DNA damage. If left unrepaired, this damage can create serious and even lethal chromosomal aberrations. Ionizing radiation can produce reactive oxygen species, which are very damaging to DNA.[22]

Ionizing radiation does direct damage to cells by causing localized ionization events, creating clusters of DNA damage.[23] This damage includes loss of nucleobases and breakage of the sugar-phosphate backbone that binds to the nucleobases. Breakages can happen to one or both of the backbone strands. Single-stranded breakages are easier to repair than double-stranded breakages, because there is still an unbroken complementary strand to use as a template. The DNA organization at the level of histones, nucleosomes, and chromatin also affects its susceptibility to radiation damage.[24]

Clustered damage, defined as at least two lesions within a helical turn, is especially harmful.[23] While DNA damage happens frequently and naturally in the cell from endogenous sources, clustered damage is a unique effect of radiation exposure.[25] Clustered damage takes longer to repair than isolated breakages, and is less likely to be repaired at all.[26] Larger radiation doses are more prone to cause tighter clustering of damage, and closely localized damage is increasingly less likely to be repaired.[23]

Somatic mutations cannot be passed down from parent to offspring, but these mutations can propagate in cell lines within an organism. Radiation damage can also cause chromosome and chromatid aberrations, and their effect depends on what stage of the mitotic cycle the cell is currently in when the irradiation occurs. If the cell is in interphase, while it is still a single strand of chromatin, the damage will be replicated during the S1 phase of cell cycle, and there will be a break on both chromosome arms. Then the damage will be apparent in both daughter cells. If the irradiation occurs after replication, only one arm will bear the damage. This damage will only be apparent in one daughter cell. A damaged chromosome may cyclize, binding to another chromosome, or to itself.[27]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is typically made based on a history of significant radiation exposure and suitable clinical findings.[2] An absolute lymphocyte count can give a rough estimate of radiation exposure.[2] Time from exposure to vomiting can also give estimates of exposure levels if they are less than 1000 rad.[2]

Prevention

Time

The longer that humans are subjected to radiation the larger the dose will be. The advice in the nuclear war manual entitled "Nuclear War Survival Skills" published by Cresson Kearny in the U.S. was that if one needed to leave the shelter then this should be done as rapidly as possible to minimize exposure.[28]

In chapter 12, he states that "[q]uickly putting or dumping wastes outside is not hazardous once fallout is no longer being deposited. For example, assume the shelter is in an area of heavy fallout and the dose rate outside is 400 roentgen (R) per hour, enough to give a potentially fatal dose in about an hour to a person exposed in the open. If a person needs to be exposed for only 10 seconds to dump a bucket, in this 1/360 of an hour he will receive a dose of only about 1 R. Under war conditions, an additional 1-R dose is of little concern." In peacetime, radiation workers are taught to work as quickly as possible when performing a task which exposes them to radiation. For instance, the recovery of a radioactive source should be done as quickly as possible.

Distance

Increasing distance from the radiation source reduces the dose according to the inverse-square law for a point source. Distance can sometimes be effectively increased by means as simple as handling a source with forceps rather than fingers. This could reduce erythema to the fingers, but the extra few centimeters distance from the body will give little protection from acute radiation syndrome.

Shielding

Matter attenuates radiation in most cases, so placing any mass (e.g., lead, dirt, sandbags, vehicles) between humans and the source will reduce the radiation dose. This is not always the case, however; care should be taken when constructing shielding for a specific purpose. For example, although high atomic number materials are very effective in shielding photons, using them to shield beta particles may cause higher radiation exposure due to the production of bremsstrahlung x-rays, and hence low atomic number materials are recommended. Also, using material with a high neutron activation cross section to shield neutrons will result in the shielding material itself becoming radioactive and hence more dangerous than if it were not present.

There are many types of shielding strategies which can be used to reduce the effects of radiation exposure. Internal contamination protective equipment such as respirators are used to prevent internal deposition as a result of inhalation and ingestion of radioactive material. Dermal protective equipment, which protects against external contamination, provides shielding to prevent radioactive material from being deposited on external structures.[29] While these protective measures do provide a barrier from radioactive material deposition, they do not shield from externally penetrating gamma radiation. This leaves anyone exposed to penetrating gamma rays at high risk of Acute Radiation Syndrome.

Naturally, shielding the entire body from high energy gamma radiation is optimal, but the required mass to provide adequate attenuation makes functional movement nearly impossible. In the event of a radiation catastrophe, medical and security personnel need mobile protection equipment in order to safely assist in containment, evacuation, and many other necessary public safety objectives.

Research has been done exploring the feasibility of partial body shielding, a radiation protection strategy which provides adequate attenuation to only the most radio-sensitive organs and tissues inside the body. Irreversible stem cell damage in the bone marrow is the first life-threatening effect of intense radiation exposure and therefore one of the most important bodily elements to protect. Due to the regenerative property of hematopoietic stem cells, it is only necessary to protect enough bone marrow to repopulate the exposed areas of the body with the shielded supply.[30] This concept allows for the development of lightweight mobile radiation protection equipment, which provides adequate protection, deferring the onset of Acute Radiation Syndrome to much higher exposure doses. One example of such equipment is the 360 gamma, a radiation protection belt which applies selective shielding to protect the bone marrow stored in the pelvic area as well as other radio sensitive organs in the abdominal region without hindering functional mobility.

More information on bone marrow shielding can be found in the Health Physics Radiation Safety Journal article Selective Shielding of Bone Marrow: An Approach to Protecting Humans from External Gamma Radiation, or in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the Nuclear Energy Agency (NEA)'s 2015 report: Occupational Radiation Protection in Severe Accident Management.

Reduction of incorporation

Where radioactive contamination is present, a gas mask, dust mask, or good hygiene practices may offer protection, depending on the nature of the contaminant. Potassium iodide (KI) tablets can reduce the risk of cancer in some situations due to slower uptake of ambient radioiodine. Although this does not protect any organ other than the thyroid gland, their effectiveness is still highly dependent on the time of ingestion which would protect the gland for the duration of a twenty-four-hour period. They do not prevent acute radiation syndrome as they provide no shielding from other environmental radionuclides.[31]

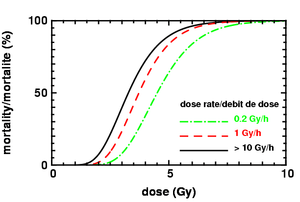

Fractionation of dose

If an intentional dose is broken up into a number of smaller doses, with time allowed for recovery between irradiations, the same total dose causes less cell death. Even without interruptions, a reduction in dose rate below 0.1 Gy/h also tends to reduce cell death.[20] This technique is routinely used in radiotherapy.

The human body contains many types of cells and a human can be killed by the loss of a single type of cells in a vital organ. For many short term radiation deaths (3 days to 30 days), the loss of two important types of cells that are constantly being regenerated causes death. The loss of cells forming blood cells (bone marrow) and the cells in the digestive system (microvilli which form part of the wall of the intestines) is fatal.

Management

Treatment is supportive with the use of antibiotics, blood products, colony stimulating factors, and stem cell transplant as clinically indicated.[2] Symptomatic measures may also be employed.[2]

Antimicrobials

There is a direct relationship between the degree of the neutropenia that emerges after exposure to radiation and the increased risk of developing infection. Since there are no controlled studies of therapeutic intervention in humans, most of the current recommendations are based on animal research.

The treatment of established or suspected infection following exposure to radiation (characterized by neutropenia and fever) is similar to the one used for other febrile neutropenic patients. However, important differences between the two conditions exist. Individuals that develop neutropenia after exposure to radiation are also susceptible to irradiation damage in other tissues, such as the gastrointestinal tract, lungs and central nervous system. These patients may require therapeutic interventions not needed in other types of neutropenic patients. The response of irradiated animals to antimicrobial therapy can be unpredictable, as was evident in experimental studies where metronidazole[32] and pefloxacin[33] therapies were detrimental.

Antimicrobials that reduce the number of the strict anaerobic component of the gut flora (i.e., metronidazole) generally should not be given because they may enhance systemic infection by aerobic or facultative bacteria, thus facilitating mortality after irradiation.[34]

An empirical regimen of antimicrobials should be chosen based on the pattern of bacterial susceptibility and nosocomial infections in the affected area and medical center and the degree of neutropenia. Broad-spectrum empirical therapy (see below for choices) with high doses of one or more antibiotics should be initiated at the onset of fever. These antimicrobials should be directed at the eradication of Gram-negative aerobic bacilli ( i.e., Enterobacteriace, Pseudomonas ) that account for more than three quarters of the isolates causing sepsis. Because aerobic and facultative Gram-positive bacteria (mostly alpha-hemolytic streptococci) cause sepsis in about a quarter of the victims, coverage for these organisms may also be needed.[35]

A standardized management plane of febrile, neutropenic patients must be devised in each institution or agency. Empirical regimens must contain antibiotics broadly active against Gram-negative aerobic bacteria (quinolones: i.e., ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, a third- or fourth-generation cephalosporin with pseudomonal coverage: e.g., cefepime, ceftazidime, or an aminoglycoside: i.e. gentamicin, amikacin).[36]

History

Acute effects of ionizing radiation were first observed when Wilhelm Röntgen intentionally subjected his fingers to X-rays in 1895. He published his observations concerning the burns that developed, though he misattributed them to ozone, a free radical produced in air by X-rays. Other free radicals produced within the body are now understood to be more important. His injuries healed later.

The Radium Girls were female factory workers who contracted radiation poisoning from painting watch dials with self-luminous paint at the United States Radium factory in Orange, New Jersey, around 1917.

Ingestion of radioactive materials caused many radiation-induced cancers in the 1930s, but no one was exposed to high enough doses at high enough rates to bring on acute radiation syndrome. Marie Curie died of aplastic anemia caused by radiation, a possible early incident of acute radiation syndrome.

The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki resulted in high acute doses of radiation to a large number of Japanese, allowing for greater insight into its symptoms and dangers. Red Cross Hospital Surgeon Terufumi Sasaki led intensive research into the syndrome in the weeks and months following the Hiroshima bombings. Dr Sasaki and his team were able to monitor the effects of radiation in patients of varying proximities to the blast itself, leading to the establishment of three recorded stages of the syndrome. Within 25–30 days of the explosion, the Red Cross surgeon noticed a sharp drop in white blood cell count and established this drop, along with symptoms of fever, as prognostic standards for Acute Radiation Syndrome.[37] Actress Midori Naka, who was present during the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, was the first incident of radiation poisoning to be extensively studied. Her death on 24 August 1945, was the first death ever to be officially certified as a result of acute radiation syndrome (or "Atomic bomb disease").

Notable incidents

There are two major databases that track radiation accidents: The American ORISE REAC/TS and the European IRSN ACCIRAD. REAC/TS shows 417 accidents occurring between 1944 and 2000, causing about 3000 cases of acute radiation syndrome, of which 127 were fatal.[38] ACCIRAD lists 580 accidents with 180 ARS fatalities for an almost identical period.[39] The two deliberate bombings are not included in either database, nor are any possible radiation-induced cancers from low doses. The detailed accounting is difficult because of confounding factors. ARS may be accompanied by conventional injuries such as steam burns, or may occur in someone with a pre-existing condition undergoing radiotherapy. There may be multiple causes for death, and the contribution from radiation may be unclear. Some documents may incorrectly refer to radiation-induced cancers as radiation poisoning, or may count all overexposed individuals as survivors without mentioning if they had any symptoms of ARS. The table below attempts to catalog some cases of ARS. Many of these incidents involved additional fatalities from other causes, such as cancer, which are excluded from this table.

Other animals

Thousands of scientific experiments have been performed to study acute radiation syndrome in animals. There is a simple guide for predicting survival/death in mammals, including humans, following the acute effects of inhaling radioactive particles.[55]

See also

References

- 1 2 "Radiation Exposure and Contamination - Injuries; Poisoning - Merck Manuals Professional Edition". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Retrieved 2017-09-06.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Donnelly EH, Nemhauser JB, Smith JM, et al. (June 2010). "Acute radiation syndrome: assessment and management". South. Med. J. 103 (6): 541–546. doi:10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181ddd571. PMID 20710137.

- ↑ Xiao M, Whitnall MH (January 2009). "Pharmacological countermeasures for the acute radiation syndrome". Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2 (1): 122–133. doi:10.2174/1874467210902010122. PMID 20021452.

- ↑ "Acute Radiation Syndrome". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2005-05-20. Archived from the original on 2015-12-04.

- ↑ "Acute Radiation Syndrome" (PDF). National Center for Environmental Health/Radiation Studies Branch. 2002-04-09. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2009-02-25. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- 1 2 3 "Acute Radiation Syndrome: A Fact Sheet for Physicians". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2005-03-18. Archived from the original on 2006-07-16.

- ↑ Reeves GI, Ainsworth EJ (May 1995). "Description of the chronic radiation syndrome in humans irradiated in the former Soviet Union". Radiation Research. 142 (2): 242–3. doi:10.2307/3579035. PMID 7724741.

- ↑ Richardson, David B.; Cardis, Elisabeth; Daniels, Robert D.; Gillies, Michael; O’Hagan, Jacqueline A.; Hamra, Ghassan B.; Haylock, Richard; Laurier, Dominique; Leuraud, Klervi (2015-10-20). "Risk of cancer from occupational exposure to ionising radiation: Retrospective cohort study of workers in France, the United Kingdom, and the United States (INWORKS)". British Medical Journal. 351: h5359. doi:10.1136/bmj.h5359. ISSN 1756-1833. PMC 4612459. PMID 26487649. Archived from the original on 2017-09-06.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-09-06. Retrieved 2017-09-06.

- ↑ Christensen DM, Iddins CJ, Sugarman SL (February 2014). "Ionizing radiation injuries and illnesses". Emerg Med Clin North Am. 32 (1): 245–65. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2013.10.002. PMID 24275177.

- ↑ The medical handling of skin lesions following high level accidental irradiation, IAEA Advisory Group Meeting, September 1987 Paris.

- ↑ Wells J; et al. (1982), "Non-Uniform Irrradiation of Skin: Criteria for limiting non-stochastic effects", Proceedings of the Third International Symposium of the Society for Radiological Protection, Advances in Theory and Practice, 2, pp. 537–542, ISBN 0-9508123-0-7

- ↑ Kerr, Richard (31 May 2013). "Radiation will make astronauts' trip to Mars even riskier". Science. 340 (6136): 1031. doi:10.1126/science.340.6136.1031. PMID 23723213. Archived from the original on 9 June 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ↑ Zeitlin, C.; et al. (31 May 2013). "Measurements of Energetic Particle Radiation in Transit to Mars on the Mars Science Laboratory". Science. 340 (6136): 1080–1084. doi:10.1126/science.1235989. Archived from the original on 8 June 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ↑ Chang, Kenneth (30 May 2013). "Data Point to Radiation Risk for Travelers to Mars". New York Times. Archived from the original on 31 May 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ↑ Gelling, Cristy (June 29, 2013). "Mars trip would deliver big radiation dose; Curiosity instrument confirms expectation of major exposures". Science News. 183 (13): 8. Archived from the original on July 15, 2013. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ↑ William C. Inkret; Charles B. Meinhold; John C. Taschner (1995). "A Brief History of Radiation Protection Standards" (PDF). Los Alamos Science (23): 116–123. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 October 2012. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- ↑ "Superflares could kill unprotected astronauts". New Scientist. 21 March 2005. Archived from the original on 27 March 2015.

- ↑ National Research Council (U.S.). Ad Hoc Committee on the Solar System Radiation Environment and NASA's Vision for Space Exploration (2006). Space Radiation Hazards and the Vision for Space Exploration. National Academies Press. ISBN 978-0-309-10264-3. Archived from the original on 2010-03-28.

- 1 2 Template:Cite journa l

- ↑ The Effects of Nuclear Weapons (Revised ed.). US Department of Defense. 1962. p. 579.

- ↑ Yu Y; Cui Y; Niedernhofer L; Wang Y (2016). "Occurrence, biological consequences and human health relevance of oxidative stress-induced DNA damage". Chemical Research in Toxicology. 29: 2008–2039.

- 1 2 3 Eccles L.; O’Neill P.; Lomax M. (2011). "Delayed repair of radiation induced DNA damage: Friend or foe?". Mutation Research. 711: 134–141.

- ↑ Lavelle C.; Foray N. (2014). "Chromatin structure and radiation-induced DNA damage: From structural biology to radiobiology". International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 49: 84–97.

- ↑ Goodhead D. (1994). "Initial events in the cellular effects of ionizing radiations: Clustered damage in DNA". International Journal of Radiation Biology. 65: 7–17.

- ↑ Georgakilas A.; Bennett P.; Wilson D.; Sutherland B. (2004). "Processing of bistranded abasic DNA clusters in gamma-irradiated human hematopoietic cells". Nucleic Acids Research. 32: 5609–5620.

- ↑ Hall E.; Giaccia A. (2006). Radiobiology for the Radiobiologist (Sixth ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- ↑ Kearny, Cresson H. (1988). Nuclear War Survival Skills. Oregon Institute of Science and Medicine. ISBN 0-942487-01-X. Archived from the original on 2017-10-17.

- ↑ "Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) in a Radiation Emergency - Radiation Emergency Medical Management". www.remm.nlm.gov. Retrieved 2018-06-26.

- ↑ Waterman, Gideon; Kase, Kenneth; Orion, Itzhak; Broisman, Andrey; Milstein, Oren (September 2017). "Selective Shielding of Bone Marrow". Health Physics. 113 (3): 195–208. doi:10.1097/hp.0000000000000688. ISSN 0017-9078.

- ↑ "Radiation and its Health Effects". Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Archived from the original on 2013-10-14. Retrieved 2013-11-19.

- ↑ Brook I, Ledney GD (1994). "Effect of antimicrobial therapy on the gastrointestinal bacterial flora, infection and mortality in mice exposed to different doses of irradiation". Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 33: 63–74. doi:10.1093/jac/33.1.63. ISSN 1460-2091.

- ↑ Patchen ML, Brook I, Elliott TB, Jackson WE (1993). "Adverse effects of pefloxacin in irradiated C3H/HeN mice: correction with glucan therapy". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 37 (9): 1882–9. doi:10.1128/AAC.37.9.1882. ISSN 0066-4804. PMC 188087. PMID 8239601.

- ↑ Brook I, Walker RI, MacVittie TJ (1988). "Effect of antimicrobial therapy on the bowel flora and bacterial infection in irradiated mice". International Journal of Radiation Biology. 53 (5): 709–718. doi:10.1080/09553008814551081. ISSN 1362-3095.

- ↑ Brook I, Ledney D (1992). "Quinolone therapy in the management of infection after irradiation". Crit Rev Microbiol: 18235–18246.

- ↑ Brook I, Elliot TB, Ledney GD, Shomaker MO, Knudson GB (2004). "Management of postirradiation infection: lessons learned from animal models". Military Medicine. 169: 194–197. ISSN 0026-4075.

- ↑ Carmichael, Ann G. (1991). Medicine: A Treasury of Art and Literature. New York: Harkavy Publishing Service. p. 376. ISBN 0-88363-991-2.

- ↑ Turai, István; Veress, Katalin (2001). "Radiation Accidents: Occurrence, Types, Consequences, Medical Management, and the Lessons to be Learned". Central European Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 7 (1): 3–14. Archived from the original on 2013-05-15. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ↑ Chambrette, V.; Hardy, S.; Nenot, J. C. (2001). "Les accidents d'irradiation: Mise en place d'une base de données "ACCIRAD" à I'IPSN" (PDF). Radioprotection. 36 (4): 477–510. doi:10.1051/radiopro:2001105. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- 1 2 Goldfarb, Alex; Litvinenko, Marina (2007). Death of a Dissident: The poisoning of Alexander Litvinenko and the return of the KGB. Simon & Schuster UK. ISBN 978-1-4711-0301-8. Archived from the original on 2016-12-22 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Johnston, Wm. Robert. "K-19 submarine reactor accident, 1961". Database of radiological incidents and related events. Johnston's Archive. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ↑ Johnston, Wm. Robert. "K-27 submarine reactor accident, 1968". Database of radiological incidents and related events. Johnston's Archive. Archived from the original on 8 February 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ↑ "Lost Iridium-192 Source". Archived from the original on 2014-11-29.

- ↑ Johnston, Wm. Robert. "K-431 submarine reactor accident, 1985". Database of radiological incidents and related events. Johnston's Archive. Archived from the original on 31 May 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ↑ "The Radiological Accident in Goiania" (PDF). p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-12.

- ↑ "Strengthening the Safety of Radiation Sources" (PDF). p. 15. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-06-08.

- ↑ Gusev, Igor; Guskova, Angelina; Mettler, Fred A. (12 December 2010). Medical Management of Radiation Accidents (Second ed.). CRC Press. pp. 299–303. ISBN 978-1-4200-3719-7. Archived from the original on 13 September 2014 – via Google Books.

- 1 2 Bagla, Pallava (7 May 2010). "Radiation Accident a 'Wake-Up Call' For India's Scientific Community". Science. 328 (5979): 679. doi:10.1126/science.328.5979.679-a. PMID 20448162.

- ↑ International Atomic Energy Agency. "Investigation of an accidental Exposure of radiotherapy patients in Panama" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-07-30.

- ↑ Johnston, Robert (September 23, 2007). "Deadliest radiation accidents and other events causing radiation casualties". Database of Radiological Incidents and Related Events. Archived from the original on 23 October 2007.

- ↑ Patterson AJ (2007). "Ushering in the era of nuclear terrorism". Critical Care Medicine. 35 (3): 953–954. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000257229.97208.76. PMID 17421087.

- ↑ Acton JM, Rogers MB, Zimmerman PD (September 2007). "Beyond the Dirty Bomb: Re-thinking Radiological Terror". Survival. 49 (3): 151–168. doi:10.1080/00396330701564760.

- ↑ Sixsmith, Martin (2007). The Litvinenko File: The Life and Death of a Russian Spy. True Crime. p. 14. ISBN 0-312-37668-5.

- ↑ Bremer Mærli, Morten. "Radiological Terrorism: "Soft Killers"". Bellona Foundation. Archived from the original on 2007-12-17.

- ↑ Wells J (1976). "A guide to the prognosis for survival in mammals following the acute effects of inhaled radioactive particles". Journal of the Institution of Nuclear Engineers. 17 (5): 126–131. ISSN 0368-2595.

Further reading

- Hachiya, Michihiko (1955). Hiroshima Diary. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina. ISBN 0-8078-4547-7.

- Hersey, John (1985) [1946]. Hiroshima (1985 new chapter ed.). New York, NY: Vintage. ISBN 0-679-72103-7.

- Masuji, Ibuse (1969). Black Rain. ISBN 0-87011-364-X.

- Sternglass, Ernest J. (1981). Secret Fallout: Low-level radiation from Hiroshima to Three-Mile Island. ISBN 0-07-061242-0.

- Norman, Norman; Wasserman, Harvey (1982). Killing Our Own: The Disaster of America's Experience with Atomic Radiation, 1945–1982. New York, NY: Dell. ISBN 0-385-28537-X. , ISBN 0-385-28536-1, ISBN 0-440-04567-3

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Radiation health effects. |

- "Fact sheet on Acute Radiation Syndrome". Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 2006-07-16. Retrieved 2006-07-22.

- "List of radiation accidents and other events causing radiation casualties".

- "The criticality accident in Sarov" (PDF). International Atomic Energy Agency. 2001. — A well documented account of the biological effects of a criticality accident.

- "Armed Forces Radiobiology Research Institute".

- This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Armed Forces Radiobiology Research Institute and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention