Death of Elaine Herzberg

| Elaine Herzberg | |

|---|---|

| Born |

Elaine Marie Wood August 2, 1968 Phoenix, Arizona, U.S.[1] |

| Died |

March 18, 2018 (aged 49) Tempe, Arizona, U.S. |

| Burial place | Phoenix, Arizona[1] |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Apache Junction High School, Apache Junction, Arizona[1] |

| Known for | First pedestrian to be killed by a self-driving car |

| Home town | Tempe, Arizona |

| Spouse(s) | Mike Herzberg (until his death); Rolf Erich Ziemann (until Elaine's death)[1] |

The death of Elaine Herzberg (August 2, 1968 – March 18, 2018) was the first recorded case of a pedestrian killed by a self-driving (autonomous) car, following a collision that occurred late in the evening of March 18, 2018. Herzberg was pushing a bicycle across a four-lane road in Tempe, Arizona, United States, when she was struck by an Uber taxi, which was operating in self-drive mode with a human safety backup driver sitting in the driving seat. Following the collision, Herzberg was taken to hospital where she died of her injuries.[2][3][4]

As a result of the fatal incident, Uber immediately suspended testing of self-driving vehicles in Arizona,[5] where such testing had been welcomed since August 2016.[6] Uber also decided not to renew its permit for autonomous vehicle testing in California when it expired at the end of March 2018.[7]

A Washington Post reporter compared Herzberg's fate with that of Bridget Driscoll who, in the United Kingdom in 1896, was the first pedestrian to be killed by an automobile.[8]

Collision summary

Herzberg was crossing Mill Avenue (North) from west to east, approximately 360 feet (110 m) south of the intersection with Curry Road, outside the crosswalk,[9][10] close to the Red Mountain Freeway. She was pushing a bicycle laden with shopping,[2] and had crossed at least two lanes of traffic when she was struck[5] at approximately 9:58 pm MST (UTC-7)[9] by the autonomous car, an Uber Volvo XC90 taxi, which was travelling north on Mill.[11][12] The vehicle had been operating in autonomous mode[13] since 9:39 pm, nineteen minutes before it struck and killed Herzberg.[9] It seems that the car's human safety backup driver, Ms. Rafaela Vasquez,[2] did not intervene before the collision as the vehicle did not appear to slow down or swerve.[14] Vehicle telemetry obtained after the crash showed that the human operator responded by moving the steering wheel less than a second before impact, and she engaged the brakes less than a second after impact.[9]

Cause investigation

The first accounts of the crash were conflicting in terms of vehicle speed and posted speed limit,[15][16] with some of the disparity sourced to a preliminary police investigation, which incorrectly stated that the car was traveling at 38 mph (61 km/h) in a 35 mph (56 km/h) zone and did not attempt to brake. The New York Times later reported the speed limit was 45 mph (72 km/h).[17] Evidence subsequently surfaced of a cozy relationship between Uber and the state Governor that allowed and protected an immature technology on the streets, and may have influenced preliminary conclusions of the accident.[18][19] Moreover, the county district attorney's office recused itself from the investigation, due to a prior joint partnership with Uber promoting their services as an alternative to driving under the influence of alcohol.[20] Some later points of focus by federal investigators have indicated that the absolute maximum speed permitted by law may not be material in the nocturnal crash.

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) sent a team of federal investigators to gather data from vehicle instruments, and to examine vehicle condition along with the actions taken by the safety driver.[21] Their preliminary findings were substantiated by many event data recorders and proved the vehicle was traveling 43 miles per hour (69 km/h) when Elaine was first detected 6 seconds (378 feet) before impact; it was unable to determine that emergency braking was needed another 4 more seconds.[9] A vehicle traveling 45 mph (72 km/h) can generally stop within 195 feet (59 m).[22] Because the machine needed to be 1.3 seconds (76 feet) away prior to discerning that emergency braking was required, whereas at least that much distance was required to stop, it was exceeding its assured clear distance ahead,[23] and hence driving too fast for the conditions.[24][25][26][27][9] A total stopping distance of 76 feet itself would imply a safe speed under 25 mph,[22] whereas human intervention was still legally required. Computer perception-reaction time would have been a speed limiting factor had the technology been superior to humans in ambiguous situations; however, the nascent computerized braking technology was disabled the day of the crash, and the machine's apparent 4 second perception-reaction (alarm) time was instead an added delay to the still requisite 1-2 second human perception-reaction time. Video released by the police on March 21 showed the safety driver was not watching the road moments before the vehicle struck Herzberg.[28] Notwithstanding perception and reaction times, 43 mph also commands a braking distance slightly greater than 76 feet.[22]

Environment

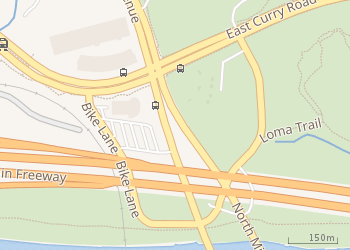

|

| Vicinity of Mill Avenue (running north-south) and Curry/Washington (east-west) in Tempe, Arizona |

Tempe Police Chief Sylvia Moir stated the collision was "unavoidable" based on the initial police investigation, which included a review of the video captured by an onboard camera.[29] Moir faulted Herzberg for crossing the road in an unsafe manner: "It is dangerous to cross roadways in the evening hour when well-illuminated, managed crosswalks are available."[30] According to Uber, safety drivers were trained to keep their hands very close to the wheel all the time while driving the vehicle so they were ready to quickly take control if necessary.[31]

The driver said it was like a flash, the person walked out in front of them. His [sic] first alert to the collision was the sound of the collision. [...] it’s very clear it would have been difficult to avoid this collision in any kind of mode (autonomous or human-driven) based on how she came from the shadows right into the roadway.

.jpg)

Tempe police released video on March 21 showing footage recorded by two onboard cameras: one forward-looking, and one capturing the safety driver's actions. The forward-facing video shows the autonomous car was traveling in the far right lane when it struck Herzberg. The driver-facing video shows the safety driver was looking down prior to the collision.[5] The Uber operator is responsible for intervening and taking manual control when necessary as well as for monitoring diagnostic messages, which are displayed on a screen in the center console. In an interview conducted after the crash with NTSB, the driver stated she was monitoring the center stack at the time of the collision.[9]

After the video was released, journalist Carolyn Said noted the police explanation of Herzberg's path meant she had already crossed two lanes of traffic before she was struck by the autonomous vehicle.[5] The Marquee Theatre and Tempe Town Lake are west of Mill Avenue, and pedestrians commonly cross mid-street without detouring north to the crosswalk at Curry.[12] According to reporting by the Phoenix New Times, Mill Avenue contains what appears to be a brick-lined path in the median between the northbound and southbound lanes.[12] However, posted signs prohibit pedestrians from using it, as it is strictly ornamental.[32]

Software issues

Michael Ramsey, an autonomous car expert with Gartner, characterized the video as showing "a complete failure of the system to recognize an obviously seen person who is visible for quite some distance in the frame. Uber has some serious explaining to do about why this person wasn’t seen and why the system didn’t engage."[5]

James Arrowood, a lawyer specializing in driverless cars in Arizona, noted the software may have decided to proceed after assuming that Herzberg would yield the right of way.[14] Arizona law (ARS 28-793)[33] states that pedestrians crossing the street outside a crosswalk shall yield to cars.[12] Per Arrowood, "The computer makes a decision. It says, 'Hey, there is this object moving 10 or 15 feet to left of me, do I move or not?' It (could be) programmed, I have a right of way, on the assumption that whatever is moving will yield the right of way."[14]

As of March 2018, Uber autonomous vehicles were unable to meet a self-imposed goal of 13 mi (21 km) between manual interventions. For comparison, autonomous vehicles from Waymo were reaching 5,600 mi (9,000 km) and vehicles from Cruise Automation were exceeding 1,200 mi (1,900 km) between interventions.[34]

.png)

The recorded telemetry showed the system had detected Herzberg six seconds before the crash, and classified her first as an unknown object, then as a vehicle, and finally as a bicycle, each of which had a different predicted path according to the autonomy logic. 1.3 seconds prior to the impact, the system determined that emergency braking was required, which is normally performed by the vehicle operator. However, the system was not designed to alert the operator, and did not make an emergency stop on its own accord, as "emergency braking maneuvers are not enabled while the vehicle is under computer control, to reduce the potential for erratic vehicle behavior", according to Uber.[9]

Sensor issues

Brad Templeton, who provided consulting for autonomous driving competitor Waymo, noted the car was equipped with advanced sensors, including radar and LiDAR, which would not have been affected by the darkness. Templeton stated "I know the [sensor] technology is better than that, so I do feel that it must be Uber’s failure."[5] Arrowood also recognized potential sensor issues: "Really what we are going to ask is, at what point should or could those sensors recognize the movement off to the left. Presumably she was somewhere in the darkness."[14]

In a press event conducted by Uber in Tempe in 2017, safety drivers touted the sensor technology, saying they were effective at anticipating jaywalkers, especially in the darkness, stopping the autonomous vehicles before the safety driver can even see pedestrians. However, manual intervention by the safety drivers was required to avoid a collision with another vehicle on at least one instance with a reporter from The Arizona Republic riding along.[35]

Uber announced they would replace their Ford Fusion-based autonomous fleet with cars based on the Volvo XC90 in August 2016; the XC90s sold to Uber would be prepared to receive Uber's vehicle control hardware and software, but would not include any of Volvo's own advanced driver-assistance systems.[36] Uber characterized the sensor suite attached to the Fusion as the "desktop" model, and the one attached to the XC90 as the "laptop", hoping to develop the "smartphone" soon.[37] According to Uber, the suite for the XC90 was developed in approximately four months.[38] The XC90 as modified by Uber included a single roof-mounted LiDAR sensor and 10 radar sensors, providing 360° coverage around the vehicle. In comparison, the Fusion had seven LiDAR sensors (including one mounted on the roof) and seven radar sensors. According to Velodyne, the supplier of Uber's LiDAR, the single roof-mounted LiDAR sensor has a narrow vertical range that prevents it from detecting obstacles low to the ground, creating a blind spot around the vehicle. Marta Hall, the president of Velodyne commented "If you’re going to avoid pedestrians, you’re going to need to have a side lidar to see those pedestrians and avoid them, especially at night." However, the augmented radar sensor suite would be able to detect obstacles in the LiDAR blind spot.[39]

Distraction

On Thursday, June 21, the Tempe Police Department released a detailed report along with media captured after the collision, including an audio recording of the 911 call made by the safety driver, Rafaela Vasquez and an initial on-scene interview with a responding officer, captured by body worn video. After the crash, police obtained search warrants for Vasquez's cellphones as well as records from the video streaming services Netflix, YouTube, and Hulu. The investigation concluded that because the data showed she was streaming The Voice over Hulu at the time of the collision, and the driver-facing camera in the Volvo showed "her face appears to react and show a smirk or laugh at various points during the time she is looking down", Vasquez may have been distracted from her primary job of monitoring road and vehicle conditions.[40] Tempe police concluded the crash was "entirely avoidable"[41] and faulted Vasquez for her "disregard for assigned job function to intervene in a hazardous situation".[40]

Records indicate that streaming began at 9:16 pm and ended at 9:59 pm. Based on an examination of the video captured by the driver-facing camera, Vasquez was looking down toward her right knee 166 times for a total of 6 minutes, 47 seconds[40] during the 21 minutes, 48 seconds preceding the crash.[42] Just prior to the crash, Vasquez was looking at her lap for 5.3 seconds; she looked up half a second before the impact.[41][43] Vasquez stated in her post-crash interview with the NTSB that she had been monitoring system messages on the center console, and that she did not use either one of her cell phones until she called 911.[9] According to an unnamed Uber source, safety drivers are not responsible for monitoring diagnostic messages.[44] Vasquez also told responding police officers she kept her hands near the steering wheel in preparation to take control if required, which contradicted the driver-facing video, which did not show her hands near the wheel.[40] Police concluded that given the same conditions, Herzberg would have been visible to 85% of motorists at a distance of 143 feet (44 m), 5.7 seconds before the car struck Herzberg. According to the police report, Vasquez should have been able to apply the brakes at least 0.57 seconds sooner, which would have provided Herzberg sufficient time to pass safely in front of the car.[42]

The police report was turned over to the Yavapai County Attorney's Office for review of possible manslaughter charges.[40] The Maricopa County Attorney's Office recused itself from prosecution over a potential conflict of interest, as it had earlier participated with Uber in a March 2016 campaign against drunk driving.[45]

Other factors

According to the preliminary report of the collision released by the NTSB, a toxicology report for Elaine Herzberg tested positive for methamphetamine and marijuana. This toxicology test was carried out on Ms. Herzberg after the collision.[9]

Aftermath

After the collision that killed Herzberg, Uber ceased testing autonomous vehicles in all four cities (Tempe, San Francisco, Pittsburgh, and Toronto) where it had deployed them.[5] On March 26, Arizona Governor Doug Ducey sent a letter to Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi, suspending Uber's autonomous car testing in the state. In the letter, Ducey stated "As governor, my top priority is public safety. Improving public safety has always been the emphasis of Arizona's approach to autonomous vehicle testing, and my expectation is that public safety is also the top priority for all who operate this technology in the state of Arizona."[46]

Prior to the fatal incident, Governor Ducey had encouraged Uber to enter the state.[6] Ducey signed Executive Order 2015-09 on August 25, 2015, entitled "Self-Driving Vehicle Testing and Piloting in the State of Arizona; Self-Driving Vehicle Oversight Committee", establishing a welcoming attitude to autonomous vehicle testing.[47][48] According to Ducey's office, the committee, which consists of eight state employees appointed by the governor, has met twice since it was formed.[6]

In December 2016, Ducey had released a statement welcoming Uber's autonomous cars: "Arizona welcomes Uber self-driving cars with open arms and wide open roads. While California puts the brakes on innovation and change with more bureaucracy and more regulation, Arizona is paving the way for new technology and new businesses."[49] Emails between Uber and the office of the governor showed that Ducey was informed autonomous vehicle testing would begin in August 2016, several months ahead of the official announcement welcoming Uber in December.[6] On March 1, 2018, Ducey signed Executive Order (XO) 2018-04, outlining regulations for autonomous vehicles. Notably, XO 2018-04 requires the company testing autonomous cars to provide a written statement that "the fully autonomous vehicle will achieve a minimal risk condition" if a failure occurs.[50]

Uber announced it would not renew its permit to test autonomous cars in California after the California Department of Motor Vehicles sent a letter to Uber telling the company that its permit would expire on March 31, and "any follow-up analysis or investigations from the recent crash in Arizona" would have to be addressed before the permit could be renewed.[7]

Herzberg's daughter retained the law firm Bellah Perez.[14] Uber and the husband and daughter of Elaine Herzberg quickly reached an undisclosed settlement on March 28 while local and federal authorities continued their investigation.[51]

Uber's legal woes continued with Herzberg's mother, father and son retaining legal counsel.[52]

The incident caused some companies to temporarily cease road testing of autonomous vehicles. Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang has stated "We don’t know that we would do anything different, but we should give ourselves time to see if we can learn from that incident."[53]

On May 24, NTSB released a preliminary incident report, the news release saying that Herzberg "was dressed in dark clothing, did not look in the direction of the vehicle… crossed… in a section not directly illuminated by lighting… entered the roadway from a brick median, where signs…warn pedestrians to use a crosswalk… 360 feet north." Six seconds before impact, the vehicle was traveling 43MPH, and the system identified the woman and bicycle as an unknown object, next as a vehicle, then as a bicycle.[54] Only 1.3 seconds before hitting the pedestrian with her bike did the system flag the need for emergency braking, but it failed to do so, as the car hit Herzberg at 39 MPH.[55] Alas, the vehicle operator only "engaged the steering wheel less than a second before impact and began braking less than a second after impact".

See also

- Mary Ward, the first person known to have been killed by an automobile

- Bridget Driscoll, the first pedestrian death by automobile in the United Kingdom

- Henry H. Bliss, the first automobile death in the Americas

- Robert Williams, the first person known to be killed by a robot

- Thomas Selfridge, the first person to die in an airplane crash

References

- 1 2 3 4 "In Memoriam: Elaine Marie Herzberg". www.sonoranskiesmortuaryaz.com. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- 1 2 3 Will Pavia (March 21, 2018). "Driverless Uber car 'not to blame' for woman's death". The Times. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ↑ Wakabayashi, Daisuke (March 19, 2018). "Self-Driving Uber Car Kills Pedestrian in Arizona, Where Robots Roam". The New York Times. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ↑ "Video shows moment of fatal Uber crash". March 22, 2018 – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Said, Carolyn (March 21, 2018). "Video shows Uber robot car in fatal accident did not try to avoid woman". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Harris, Mark (March 28, 2018). "Exclusive: Arizona governor and Uber kept self-driving program secret, emails reveal". The Guardian. Retrieved March 29, 2018.

- 1 2 Carolyn Said (March 27, 2018). "Uber puts the brakes on testing robot cars in California after Arizona fatality". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- ↑ Kunkle, Fredrick (March 22, 2018). "Fatal crash with self-driving car was a first — like Bridget Driscoll's was 121 years ago with one of the first cars". Washington Post. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "PRELIMINARY REPORT – HIGHWAY – HWY18MH010" (PDF) (The information in this report is preliminary and will be supplemented or corrected during the course of the investigation). National Transportation Safety Board. May 24, 2018. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- ↑ Bensinger, Greg; Higgins, Tim (March 22, 2018). "Video Shows Moments Before Uber Robot Car Rammed Into Pedestrian". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- ↑ "Self-driving Uber car hits, kills pedestrian in Tempe". ABC 15 Arizona. March 19, 2018. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Stern, Ray (March 19, 2018). "Tempe Police: Uber Self-Driving Car Didn't Brake 'Significantly' Before Killing Pedestrian". Phoenix New Times. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ↑ White, Jeremy (March 20, 2018). "Police identify first pedestrian killed by self-driving car". The Independent.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Randazzo, Ryan (March 22, 2018). "What went wrong with Uber's Volvo in fatal crash? Experts shocked by technology failure". The Arizona Republic. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ↑ Gibson, Kate (March 20, 2018). "Arizona police: Pedestrian stepped in front of self-driving Uber before crash". CBS News. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ↑ Walker, Alissa. "This is the moment when we decide that human lives matter more than cars". Curbed. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- ↑ Griggs, Troy (March 20, 2018). "How a Self-Driving Uber Killed a Pedestrian in Arizona". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- ↑ "Emails reveal Uber's cozy relationship with Arizona governor". CBS News. Associated Press. 29 March 2018.

- ↑ "Exclusive: Arizona governor and Uber kept self-driving program secret, emails reveal". The Guardian. 28 March 2018.

- ↑ Garcia, Ureil J. (31 May 2018). "Maricopa County Attorney's Office cites conflict in Tempe Uber death case". The Republic.

- ↑ "NTSB UPDATE: Uber Crash Investigation" (Press release). National Transportation Safety Board. March 21, 2018. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- 1 2 3 "VA. § 46.2-880. Tables of speed and stopping distances". Code of Virginia. State of Virginia.

an average baseline for motor vehicle stopping distances...for a vehicle in good condition and...on a level, dry stretch of highway, free from loose material.

- ↑ Isaac, Mike; Wakabayashi, Daisuke; Conger, Kate (August 19, 2018). "After Fatal Accident, Uber's Vision of Self-Driving Cars Begins to Blur" (print). The New York Times. p. B1. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

preliminary findings from federal regulators investigating the crash confirmed what many self-driving car experts suspected: Uber’s self-driving car should have detected a pedestrian with enough time to stop, but it failed to do so.

- ↑ Krishe, Tom; Billeaud, Jacques (22 June 2018). "Uber driver streaming 'The Voice' just before fatal Arizona crash, report says". Chicago Tribune. Associated Press. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

"This crash would not have occurred if Vasquez would have been monitoring the vehicle and roadway conditions and was not distracted," the report says. A crash report also indicated that the self-driving vehicle was traveling too fast for the road conditions.

- ↑ Lawyers Cooperative Publishing. New York Jurisprudence. Automobiles and Other Vehicles. Miamisburg, OH: LEXIS Publishing. p. § 720. OCLC 321177421.

It is negligence as a matter of law to drive a motor vehicle at such a rate of speed that it cannot be stopped in time to avoid an obstruction discernible within the driver's length of vision ahead of him. This rule is known generally as the `assured clear distance ahead' rule * * * In application, the rule constantly changes as the motorist proceeds, and is measured at any moment by the distance between the motorist's vehicle and the limit of his vision ahead, or by the distance between the vehicle and any intermediate discernible static or forward-moving object in the street or highway ahead constituting an obstruction in his path. Such rule requires a motorist in the exercise of due care at all times to see, or to know from having seen, that the road is clear or apparently clear and safe for travel, a sufficient distance ahead to make it apparently safe to advance at the speed employed.

- ↑ Leibowitz, Herschel W.; Owens, D. Alfred; Tyrrell, Richard A. (1998). "The assured clear distance ahead rule: implications for nighttime traffic safety and the law". Accident Analysis & Prevention. 30 (1): 93–99. doi:10.1016/S0001-4575(97)00067-5.

The assured clear distance ahead (ACDA) rule holds the operator of a motor vehicle responsible to avoid collision with any obstacle that might appear in the vehicle's path.

- ↑ "Section 2 – Driving Safely" (PDF). Commercial Driver License Manual 2005. United States Department of Transportation. July 2014. pp. 2–15, 2–19, 2–26, 13–1.

[pg 2-15] 2.6.4 – Speed and Distance Ahead: You should always be able to stop within the distance you can see ahead. Fog, rain, or other conditions may require that you slowdown to be able to stop in the distance you can see. ... [pg 2-19] 2.8.3 – Drivers Who Are Hazards: Vehicles may be partly hidden by blind intersections or alleys. If you only can see the rear or front end of a vehicle but not the driver, then he or she can't see you. Be alert because he/she may back out or enter into your lane. Always be prepared to stop. ... [pg 2-26] 2.11.4 – Vehicle Factors: Headlights. At night your headlights will usually be the main source of light for you to see by and for others to see you. You can't see nearly as much with your headlights as you see in the daytime. With low beams you can see ahead about 250 feet and with high beams about 350-500 feet. You must adjust your speed to keep your stopping distance within your sight distance. This means going slowly enough to be able to stop within the range of your headlights. ... [pg 13-1] 13.1.2 – Intersections As you approach an intersection: Check traffic thoroughly in all directions. Decelerate gently. Brake smoothly and, if necessary, change gears. If necessary, come to a complete stop (no coasting) behind any stop signs, signals, sidewalks, or stop lines maintaining a safe gap behind any vehicle in front of you. Your vehicle must not roll forward or backward. When driving through an intersection: Check traffic thoroughly in all directions. Decelerate and yield to any pedestrians and traffic in the intersection. Do not change lanes while proceeding through the intersection. Keep your hands on the wheel.

- ↑ Garcia, Uriel J.; Randazzo, Ryan (March 21, 2018). "Video shows moments before fatal Uber crash in Tempe". The Arizona Republic. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ↑ Garcia, Uriel J.; Bland, Karina (March 20, 2018). "Tempe police chief: Fatal Uber crash likely 'unavoidable' for any kind of driver". The Arizona Republic. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- 1 2 Said, Carolyn (March 19, 2018). "Exclusive: Tempe police chief says early probe shows no fault by Uber". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ↑ "Former Uber Backup Driver: 'We Saw This Coming'". CityLab. Retrieved 2018-04-29.

- ↑ Farzan, Antonia Noori (March 22, 2018). "Self-Driving Uber Crash Highlights Bigger Problem: Metro Phoenix Is Hell for Pedestrians". Phoenix New Times. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ↑ "A.R.S. 28-793. Crossing at other than crosswalk". Arizona State Legislature. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ↑ Wakabayashi, Daisuke (March 23, 2018). "Uber's Self-Driving Cars Were Struggling Before Arizona Crash". The New York Times. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ↑ Randazzo, Ryan (8 November 2017). "Here are 6 reasons Uber is betting big on Arizona". The Arizona Republic. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ↑ Golson, Jordan (18 August 2016). "Volvo and Uber ink deal to develop 'base vehicles' for autonomous cars". The Verge. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- ↑ Said, Carolyn (14 September 2016). "Uber's robot taxis hit the road in Pittsburgh". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- ↑ Harding, Xavier (14 September 2016). "We Got Behind The Wheel Of Uber's Self-Driving Car". Popular Science. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- ↑ Somerville, Heather; Lienert, Paul; Sage, Alexandria (March 27, 2018). "Uber's use of fewer safety sensors prompts questions after Arizona crash". Reuters. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Coppola, Chris; Frank, BrieAnna J (21 June 2018). "Report: Uber driver was watching 'The Voice' moments before fatal Tempe crash". AZ Central. USA Today. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

The documents indicate police are seeking manslaughter charges against Vasquez...."This crash would not have occurred if Vasquez would have been monitoring the vehicle and roadway conditions and was not distracted," the report says....A crash report indicated that the self-driving vehicle was traveling too fast for the road conditions.

- 1 2 Somerville, Heather; Shepardson, David (21 June 2018). "Uber car's 'safety' driver streamed TV show before fatal crash: police". Reuters. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- 1 2 Stern, Ray (21 June 2018). "Self-Driving Uber Crash 'Avoidable,' Driver's Phone Playing Video Before Woman Struck". Phoenix New Times. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- ↑ Lee, Timothy B. (22 June 2018). "Police: Uber driver was streaming Hulu just before fatal self-driving crash". ars Technica. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- ↑ Stern, Ray (24 May 2018). "NTSB Report Suggests Uber's Backup Driver More at Fault Than Car in Fatal Crash". Phoenix New Times. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- ↑ Garcia, Uriel J. "Maricopa County Attorney's Office cites conflict in Tempe Uber death case". The Republic. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- ↑ Randazzo, Ryan (March 26, 2018). "Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey suspends testing of Uber self-driving cars". The Arizona Republic. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ↑ Ducey, Douglas A. (25 August 2015). "Self-Driving Vehicle Testing and Piloting in the State of Arizona; Self-Driving Vehicle Oversight Committee". Office of the Governor Doug Ducey. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ↑ Kang, Cecilia (November 11, 2017). "Where Self-Driving Cars Go to Learn". The New York Times. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ↑ "Governor Ducey Tells Uber 'CA May Not Want You, But AZ Does'" (Press release). Office of the Governor Doug Ducey. December 22, 2016. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ↑ Ducey, Douglas A. (25 August 2015). "Advaincing Autonomous Vehicle Testing and Operating; Prioritizing Public Safetly". Office of the Governor Doug Ducey. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ↑ Neuman, Scott (March 29, 2018). "Uber Reaches Settlement With Family Of Arizona Woman Killed By Driverless Car". National Public Radio. Retrieved March 29, 2018.

- ↑ Schwartz, David (March 31, 2018). "More family members of woman killed in Uber self-driving car crash hire lawyer". Reuters. Retrieved April 26, 2018.

- ↑ "Jensen Huang on the Uber Tragedy and Why Nvidia Suspended Testing". IEEE Spectrum. March 30, 2018. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ↑ "Preliminary Report Released for Crash Involving Pedestrian, Uber Technologies, Inc., Test Vehicle". www.ntsb.gov. Retrieved 2018-09-11.

- ↑ "How Uber's Self-Driving System Failed to Brake and Avoid Killing Elaine Herzberg". Streetsblog USA. 2018-05-24. Retrieved 2018-09-11.

External links

- NTSB investigation of Uber crash, Accident No. HWY18FH010

- Dashcam video related to accident, via BBC

- Davies, Alex (22 June 2018). "The unavoidable folly of making humans train self-driving cars". Wired. Retrieved 26 June 2018.