Dacres Hotel

|

Dacres Hotel | |

Dacres Hotel | |

| |

| Location |

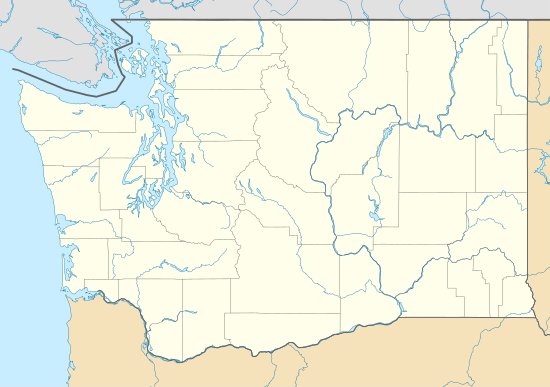

4th and Main streets Walla Walla, Washington |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 46°3′56″N 118°20′27″W / 46.06556°N 118.34083°WCoordinates: 46°3′56″N 118°20′27″W / 46.06556°N 118.34083°W |

| Built | 1873, 1899 |

| Architect | Bennes, Hendricks & Tobey (1907 remodel) |

| Architectural style | Italianate |

| NRHP reference # | 74001984[1] |

| Added to NRHP | November 5, 1974 |

The Dacres Hotel is a historic hotel in Walla Walla, Washington, United States.[1] Rebuilt from the ruins of the 1873 Stine House, Walla Walla's first brick hotel, The Italianate building was re-opened in 1899 by James E. Dacres. It operated until 1959. Currently, the building houses Main Street Studios. The building is a rare and exceptional local example the pre-fabricated cast iron facades manufactured by the Mesker Brothers. Bennes, Hendricks & Tobey remodeled the building in 1907.[1] It was added to the National Register of Historic Places on November 5, 1974.[1]

History

Stine House

Frederick Stine was born in Uniontown, Pennsylvania on November 24, 1825, one of 14 children. In the 1830s the family moved to a farm in Ohio where Frederick picked up the blacksmith trade from his father. In May of 1852 Frederick, his brothers and 23 other men set off from St. Joseph, Missouri bound for Sacramento, California, reaching their destination in a mere 2 months and 1 day. After spending time in Marysville and Yreka plying his trade, he departed for eastern Washington on a trip that would prove much more difficult than his first.[2]

Stine arrived in Walla Walla in May of 1862 from California with only the clothes on his back and 75 cents to his name. He scraped together enough loaned money to purchase a corner lot on Fourth and Main streets and build a shanty to house his blackmith shop. With the small frontier town swarming with miners and emigrants with their wagons, his shop proved very lucrative and with additional business from the cavalry stationed at Fort Walla Walla he was able to pay his debtors back within a few months.[3](pp63) In 1863 he helped form the first fire department in town and in 1865 was elected to city council where he was re-elected several times.[2] By 1872 Stine had amassed a small fortune. He moved his small shop off his lot and began construction of a 3-story brick building; first conceived as an office building, the plans soon changed into a hotel.[4] The hotel was built of bricks fired in Weston, Oregon, lime mortar shipped from San Francisco and most expensively, the glass for the windows which were made in France and shipped around Cape Horn.[2][3](pp82-83) Opened in August 1873, the Stine House was the first 3-story brick building in Walla Walla and with 50 rooms it was the largest Hotel in Washington Territory. It was designed in a simple Italianate style, with corbel window arches (which are still extant on the building's east facade), a ground floor arcade and a wooden cornice; a wooden balcony wrapped around the front of the building above the first floor. Although Stine built it and named it after himself, he never operated the hotel, opting to continue his blacksmith business at 4th and Rose streets until retiring in 1880. He died in June of 1909.[2]

The Stine became the town's social gathering place and the stopping point for all the major stage lines from Lewiston and LaGrande.[2] It even offered free carriage service between the hotel and the train depot, and reasonably priced service to anywhere else in town. The hotel was so well appointed that several local families chose to live in the hotel while renting out their own homes. The hotel became the meeting place for many dignitaries, most notably president Rutherford B. Hayes and his entourage including his wife Lucy Webb Hayes and commanding general William Tecumseh Sherman, who dined in the hotel's restaurant during his visit to Walla Walla in October 1880.[2][3](pp104)Business was good enough that the hotel was doubled in size in 1882, extending it south to the alley and bringing the room total to 100. The Stine remained the town's preeminent hotel until being gutted by a fire on July 22, 1892 that had spread from an adjacent saloon. Any attempts at rebuilding were stalled by the Panic of 1893, and it stood as an empty ruin for the rest of the decade.

Hotel Dacres

In 1899 a group of investors headed by Walla Walla pioneer George Dacres and his brother James purchased the burnt out shell of the Stine House and began to rebuild. The hotel was once again doubled in size and the entire Main street frontage was rebuilt with a pre-fabricated cast iron facade, manufactured by Mesker Brothers in St. Louis, Missouri and shipped to Walla Walla by rail. It was and is the largest Mesker facade in Washington State. The second floor was adorned with a wrought iron balcony, echoing the wooden one that had adorned the Stine.[5] On the interior, the hotel's lobby was lavishly decorated with red carpet, oak furniture, potted plants, polished brass spittoons and a grand piano. The rooms were no less accommodating and even came with a free pitcher of ice water. Other guest services included a larger restaurant, a barber shop, a Turkish Bath and later a first-class bar and a grill room featuring live music. The revived building once again became Walla Walla's premier Hotel and thanks to its proximity to the Keylor Grand Opera House, the regions's main Vaudeville venue, the Dacres would see such notable guests as Louisa May Alcott, John Philip Sousa, Harry Lauder and Al Jolson, among others.[6](pp36)

The Hotel suffered another large interior fire in 1905, caused by a shorting electrical fan, but remained open while repairs were made.[7] In 1907, the hotel's then manager, Art Harris (a previous manager of the Geyser Grand Hotel in Baker City, Oregon) commissioned Portland architects Bennes, Hendricks & Tobey to completely remodel the hotel, with plans calling for a complete interior remodel, adding 1 or even 2 floors and an elevator, but this never fully came to pass.[8][9][10] With a scaled-back interior remodeling complete, the hotel reopened on April 1, 1908, touting a new European Plan. The hotel was visited by another president, when William Howard Taft made his visit to Walla Walla in 1911.[5] By the 1920s, many other larger and more modern hotels were opening in town, and the Dacres settled in as a mid-range traveler's hotel, housing road and railroad crews and itinerant farm workers. The Hotel officially left the Dacres family in 1921 when it was sold to E.C. Davis, who previously ran the Revere Hotel in Pomeroy, Washington.[11] In 1924 Eugene Tausick, a leading businessman and the owner of the company in charge of the rival Grand Hotel, purchased the Hotel from Davis.[12] While various upgrades were made to the interior and the storefronts over the years, and while several pediments and finials were removed or lost from the top of the building, the Dacres' outward appearance remains much as it did in 1899, being spared the fate of Urban Renewal which claimed many historic buildings in the surrounding blocks in the 1950s and 60s. The hotel closed its doors on May 25, 1959, with the owners citing the state's impending $1 minimum wage law as the primary reason.[4][13] In 1966 The Tausick Estate sold the building to O.D. Keen Construction Co. who disposed of most of the hotel's furnishings, fixtures, signage and even keys at public auction.[12]

For the next few decades the building remained vacant save for several small businesses on the ground floor. In 1974, the Hotel was nominated for State and national landmark status as part of a history project by Washington State University student Robert Hergert.[5] It was accepted to the National Register in September 1974, only the second building in the County to be registered (The first being Fort Walla Walla).[14] In 1982 the building was purchased by Robert Finch who began restoration on the ground floor in earnest.[15] Currently, the ground floor is occupied by a restaurant and a real estate office while the upper floors remain closed.

External Links

Stine House [Image], Walla Walla Photographs Collection - Whitman College

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 "National Register of Historic Places – Inventory Nomination Form: Dacres Hotel". National Park Service. November 5, 1974. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Fred Stine Gave City It's First Hotel of Splendor". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Newspaper Archive. 14 June 1953.

- 1 2 3 Bennett, Robert A. (1980). Walla Walla: Portrait of a Western Town. Walla Walla: Pioneer Press Books.

- 1 2 "Historic Dacres Hotel, 'Finest of Era' Closes". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Newspaper Archive. 25 May 1959.

- 1 2 3 Orchard, Vance (10 Jul 1983). "Sousa, Jolson Once Signed Dacres Register". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ Bennett, Robert A. (1982). Walla Walla: A Town Built to Be a City. Walla Walla: Pioneer Press Books.

- ↑ "Total Loss Was $8000". The Evening Statesman. Library of Congress. 26 Jul 1905. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ↑ MacLeod, R. C. (Nov 1907). "Prominent Hotel to Be Enlarged". Up-to-the-times Magazine. 2 (1): 18. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- ↑ "Construction News". Pacific Builder and Engineer. 5 (48): 9. 30 Nov 1907. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ↑ "Walla Walla Contractors". Pacific Builder and Engineers. 6 (47): 415. 21 Nov 1908. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ↑ "The Hotel News". The Hotel World. 93 (5): 20. 30 Jul 1921. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- 1 2 "Student Retells Story of Famous Hotel". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Newspaper Archive. 16 Aug 1974.

- ↑ Stein, Alan J. "Washington Minimum Wage and Hour Act goes into effect on June 11, 1959". Historylink. Historylink.org. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ↑ Orchard, Vance (2 Jan 1975). "Walla Walla, Dayton Buildings Named to Historic Registry". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ "Hotel Dacres Rises From Ashes of Stine House". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Newspaper Archive. 25 Feb 2001.

Further reading

- Butler, Robert E. A Brief History of the Stine House and Dacres Hotel, Walla Walla, Washington January 1, 1972.