Czesław Miłosz

| Czesław Miłosz | |

|---|---|

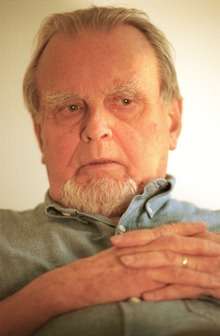

Czesław Miłosz, 1999 | |

| Born |

30 June 1911 Szetejnie, Kovno Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died |

14 August 2004 (aged 93) Kraków, Poland |

| Occupation | Poet, prose writer, essayist |

| Nationality | Polish / Lithuanian |

| Citizenship | Polish, American |

| Notable awards |

Nike Award (1998) Nobel Prize in Literature (1980) Neustadt International Prize for Literature (1978) |

|

| |

| Signature |

|

Czesław Miłosz ([ˈt͡ʂɛswaf ˈmiwɔʂ] (![]()

His World War II-era sequence The World is a collection of twenty "naïve" poems. Following the war, he served as Polish cultural attaché in Paris and Washington, D.C., and in 1951 defected to the West. His nonfiction book The Captive Mind (1953) became a classic of anti-Stalinism. From 1961 to 1998 he was a professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of California, Berkeley.

He became a U.S. citizen in 1970.[3] In 1978 he was awarded the Neustadt International Prize for Literature, and in 1980 the Nobel Prize in Literature for his poetry, essays and other writing. In 1999 he was named a Puterbaugh Fellow.[4] After the fall of the Iron Curtain, he divided his time between Berkeley, California, and Kraków, Poland.

Life in Europe

Early life

Czesław Miłosz was born in the village of Szetejnie (Lithuanian: Šeteniai), Kovno Governorate, Russian Empire (now Kėdainiai district, Kaunas County, Lithuania) on the border between two Lithuanian historical regions, Samogitia and Aukštaitija, in central Lithuania. He was the son of Aleksander Miłosz (died 1959), a Polish civil engineer of Lithuanian origin,[3][5][6][7][8] and Weronika (née Kunat; 1887-1945), a descendant of the Syruć noble family (her grandfather was Szymon Syruć).[9]

Miłosz became fluent in Polish, Lithuanian, Russian, English, and French.[10] His brother, Andrzej Miłosz (1917–2002), a Polish journalist, translator of literature and of film subtitles into Polish, was a documentary film producer. His work included Polish documentaries about his brother.

Miłosz was raised Catholic in rural Lithuania. He has emphasized his identification with the multi-ethnic Grand Duchy of Lithuania in his writings, a stance that led to ongoing controversies. He refused to identify exclusively as either a Pole or a Lithuanian.[11] He said of himself: "I am a Lithuanian to whom it was not given to be a Lithuanian",[12] and "My family in the sixteenth century already spoke Polish, just as many families in Finland spoke Swedish and in Ireland English, so I am a Polish not a Lithuanian poet. But the landscapes and perhaps the spirits of Lithuania have never abandoned me".[13]

Miłosz memorialised his Lithuanian childhood in a 1955 novel The Issa Valley and in the 1959 memoir Native Realm.[14]

He employed a Lithuanian-language tutor late in life to improve the skills acquired in his childhood. He said that it might be the language spoken in heaven.[15]

In his youth, Miłosz came to adopt, as he put it, a "scientific, atheistic position mostly", although he was later to return to the Catholic faith.[16] After graduation from Sigismund Augustus Gymnasium in Wilno (then in Poland, now Vilnius in Lithuania), he studied law at Stefan Batory University.[17]

In 1931 he traveled to Paris, where he was influenced by his distant cousin Oscar Milosz, a French poet of Lithuanian descent who had become a Swedenborgian. In 1931, he formed the poetic group Żagary with the young poets Jerzy Zagórski, Teodor Bujnicki, Aleksander Rymkiewicz, Jerzy Putrament and Józef Maśliński.[17]

Miłosz's first volume of poetry was published in Polish in 1934. After receiving his law degree that year, he spent a year in Paris on a fellowship. Upon returning, he worked as a commentator at Radio Wilno, but was dismissed. This action has been described as stemming from either his leftist views or for views overly sympathetic to Lithuania.[12][18] Miłosz wrote all his poetry, fiction and essays in Polish and translated the Old Testament Psalms into Polish.

World War II

.jpg)

Miłosz spent World War II in Warsaw, under Nazi Germany's "General Government". Here he attended underground lectures by Władysław Tatarkiewicz, the Polish philosopher and historian of philosophy and aesthetics. He did not join the Polish Home Army's resistance or participate in the Warsaw Uprising, partly from an instinct for self-preservation and partly because he saw its leadership as right-wing and dictatorial.[19]

According to Irena Grudzińska-Gross, he saw the uprising as a "doomed military effort" and lacked "patriotic elation" – he called it "a blameworthy, lightheaded enterprise."[19][20]

In his 1953 book The Captive Mind, however, Miłosz would later sharply criticize the Soviet military for remaining in their positions and making no effort to assist the Home Army's fighters. He accused them of watching through binoculars as the Polish Resistance was slaughtered and as the city was razed by Hitler's orders. Only then did the Soviets enter the city.[21]

The Holocaust

During the Holocaust in Poland, Miłosz was active in the work of Organizacja Socjalistyczno-Niepodległościowa "Wolność" ("The 'Freedom' Socialist Pro-Independence Organisation"). Among other activities for "Wolność", Miłosz aided Warsaw Jews. His brother, Andrzej, was also active in helping Jews in Nazi-occupied Poland, and, in 1943, Andrzej transported the Polish Jew Seweryn Tross and his wife from Vilnius to Warsaw. Czesław Miłosz took in the Trosses, found them a hiding place, and supported them financially. The Trosses ultimately died during the Warsaw uprising. Miłosz helped at least three other Jews – Felicja Wołkomińska and her brother and sister. For these efforts, Miłosz received the medal of the Righteous Among the Nations in Yad Vashem, Israel in 1989.[22][23]

Stalinism

After World War II, Miłosz served as cultural attaché of the newly formed People's Republic of Poland in Washington, D.C. and Paris. For this he was criticized in some emigre circles.

Conversely, he was attacked and censored in Poland when, in 1951, he defected and obtained political asylum in France. He described his life in Paris as difficult – there was still considerable intellectual sympathy for Communism. Albert Camus was supportive, but Pablo Neruda denounced him as "The Man Who Ran Away."[24] His attempts to seek asylum in the US were denied for several years, due to the climate of McCarthyism.[25]

Miłosz's 1953 book, The Captive Mind, is a study of how intellectuals behave under a repressive regime. Miłosz observed that those who became dissidents were not necessarily those with the strongest minds but rather those with the weakest stomachs; the mind can rationalize anything, he said, but the stomach can take only so much. Throughout the Cold War, the book was cited by conservatives and has been a staple in political science courses on totalitarianism. He received the Prix Littéraire Européen (European Literary Prize) for his second book The Seizure of Power,[26] which drew on his experience in Warsaw during World War II.

In 1957, Miłosz published his long poem A Treatise on Poetry, about the poetry and history of Poland in the first half of the 20th century.[27]

Life in the United States

.jpg)

In 1960 Miłosz emigrated to the United States, and in 1970 he became a U.S. citizen. In 1961 he began a professorship in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of California, Berkeley.[28]

In 1978 he received the Neustadt International Prize for Literature.[28] He retired the same year but continued teaching at Berkeley. His attitude about living in Berkeley is sensitively portrayed in his poem, "A Magic Mountain," contained in a collection of translated poems, Bells in Winter (Ecco Press, 1985).

In 1980 Miłosz received the Nobel Prize in Literature. Since his works had been banned in Poland by the communist government, this was the first time that many Poles became aware of him.[29] After the Iron Curtain fell, he was able to return to Poland, at first to visit, later to live part-time in Kraków. He divided his time between his home in Berkeley and an apartment in Kraków.

In 1977 he had been given an honorary doctorate by the University of Michigan; two weeks after he received the 1980 Nobel Prize in Literature, he returned to Michigan to lecture, and in 1983 he became the Visiting Walgreen Professor of Human Understanding. In 1989 he received the U.S. National Medal of Arts and an honorary doctorate from Harvard University.

In a 1994 interview, Miłosz spoke of the difficulty of writing religious poetry in a largely post-religious world. He reported a recent conversation with his compatriot Pope John Paul II; the latter, commenting upon some of Miłosz's work, in particular Six Lectures in Verse, said to him: "You make one step forward, one step back." The poet answered: "Holy Father, how in the twentieth century can one write religious poetry differently?" The Pope smiled.[30] A few years later, in 2000, Miłosz dedicated a rather straightforward ode to John Paul II, on the occasion of the pope's eightieth birthday.[31]

Death and legacy

Czesław Miłosz died on 14 August 2004 at his Kraków home, aged 93. He was buried in Kraków's Skałka Roman Catholic Church, becoming one of the last to be commemorated there.[32]

Protesters threatened to disrupt the proceedings on the grounds that he was anti-Polish, anti-Catholic, and had signed a petition supporting gay and lesbian freedom of speech and assembly.[33]

Pope John Paul II, along with Miłosz's confessor, issued public messages to the effect that Miłosz had been receiving the sacraments, which quelled the protest.[34]

Miłosz's first wife, Janina (née Dłuska, 1909–1986), whom he married in 1944, predeceased him, in 1986; they had two sons, Anthony (b. 1947) and John Peter (b. 1951). His second wife, Carol Thigpen (b. 1944), an American-born historian, died in 2002.

Miłosz is honoured at Israel's Yad Vashem memorial to the Holocaust, as one of the "Righteous among the Nations". A poem by Miłosz appears on a Gdańsk memorial to protesting shipyard workers who had been killed by government security forces in 1970. His books and poems have been translated by many hands, including Jane Zielonko, Peter Dale Scott, Robert Pinsky, and Robert Hass.

In November 2011, Yale University hosted a conference on Miłosz's relationship with America.[35]

The Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, which holds the Czesław Miłosz Papers,[36] also hosted an exhibition celebrating Miłosz's life and work, entitled Exile as Destiny.

Selected works

Poetry collections

- 1936: Trzy zimy (Three Winters); Warsaw: Władysława Mortkowicz

- 1945: Ocalenie (Rescue); Warsaw: Spółdzielnia Wydawnicza Czytelnik

- 1954: Światło dzienne (The Light of Day); Paris: Instytut Literacki

- 1957: Traktat poetycki (A Treatise on Poetry); Paris: Instytut Literacki

- 1962: Król Popiel i inne wiersze (King Popiel and Other Poems); Paris: Instytut Literacki

- 1965: Gucio zaczarowany (Gucio Enchanted); Paris: Instytut Literacki

- 1969: Miasto bez imienia (City Without a Name); Paris: Instytut Literacki

- 1974: Gdzie słońce wschodzi i kedy zapada (Where the Sun Rises and Where it Sets); Paris: Instytut Literacki

- 1982: Hymn o Perle (The Poem of the Pearl); Paris: Instytut Literacki

- 1984: Nieobjęta ziemia (Unattainable Earth); Paris: Instytut Literacki

- 1989: Kroniki (Chronicles); Paris: Instytut Literacki

- 1991: Dalsze okolice (Farther Surroundings); Kraków: Społeczny Instytut Wydawniczy Znak

- 1994: Na brzegu rzeki (Facing the River); Kraków: Społeczny Instytut Wydawniczy Znak

- 2000: To (It), Kraków: Społeczny Instytut Wydawniczy Znak

- 2002: Druga przestrzen (The Second Space); Kraków: Społeczny Instytut Wydawniczy Znak

- 2003: Orfeusz i Eurydyka (Orpheus and Eurydice); Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie

- 2006: Wiersze ostatnie (Last Poems) Kraków: Społeczny Instytut Wydawniczy Znak

Prose collections

- 1953: Zniewolony umysł (The Captive Mind); Paris: Instytut Literacki

- 1955: Zdobycie władzy (The Seizure of Power); Paris: Instytut Literacki

- 1955: Dolina Issy (The Issa Valley); Paris: Instytut Literacki

- 1959: Rodzinna Europa (Native Realm); Paris: Instytut Literacki

- 1969: The History of Polish Literature; London-New York: MacMillan

- 1969: Widzenia nad Zatoką San Francisco (A View of San Francisco Bay); Paris: Instytut Literacki

- 1974: Prywatne obowiązki (Private Obligations); Paris: Instytut Literacki

- 1976: Emperor of the Earth; Berkeley: University of California Press

- 1977: Ziemia Ulro (The Land of Ulro); Paris: Instytut Literacki

- 1979: Ogród Nauk (The Garden of Science); Paris: Instytut Literacki

- 1981: Nobel Lecture; New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux

- 1983: The Witness of Poetry; Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press

- 1985: Zaczynając od moich ulic (Starting from My Streets); Paris: Instytut Literacki

- 1986: A mi Európánkról (About our Europe); New York: Hill and Wang

- 1989: Rok myśliwego (A year of the hunter); Paris: Instytut Literacki

- 1992: Szukanie ojczyzny (In Search of a Homeland); Kraków: Społeczny Instytut Wydawniczy Znak

- 1995: Metafizyczna pauza (The Metaphysical Pause); Kraków: Społeczny Instytut Wydawniczy Znak

- 1996: Legendy nowoczesności (Modern Legends, War Essays); Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie

- 1997: Zycie na wyspach (Life on Islands); Kraków: Społeczny Instytut Wydawniczy Znak

- 1997: Piesek przydrożny (Roadside Dog); Kraków: Społeczny Instytut Wydawniczy Znak

- 1997: Abecadło Milosza (Milosz's Alphabet); Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie

- 1988: Inne Abecadło (A Further Alphabet); Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie

- 1999: Wyprawa w dwudziestolecie (An Excursion through the Twenties and Thirties); Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie

- 2001: To Begin Where I Am: Selected Essays; New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- 2004: Spiżarnia literacka (A Literary Larder); Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie

- 2004: Przygody młodego umysłu; Kraków: Społeczny Instytut Wydawniczy Znak

- 2004: O podróżach w czasie; (On time travel) Kraków: Społeczny Instytut Wydawniczy Znak

Novels

- 1987: The Mountains of Parnassus; Yale University Press

Translations by Miłosz

- 1996: Talking to My Body by Anna Swir translated by Czesław Miłosz and Leonard Nathan, Copper Canyon Press

See also

References

- ↑ Drabble, Margaret, ed. (1985). The Oxford Companion to English Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 652. ISBN 0-19-866130-4.

- ↑ Krzyżanowski, Julian, ed. (1986). Literatura polska: przewodnik encyklopedyczny, Volume 1: A–M. Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe. pp. 671–72. ISBN 83-01-05368-2.

- 1 2 "The Civic and the Tribal State: The State, Ethnicity, and the Multiethnic State" By Feliks Gross, pg. 124

- ↑ "Puterbaugh Festival of International Literature & Culture". World Literature Today. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ↑ Saulius Sužiedėlis (1 February 2011). Historical Dictionary of Lithuania. Scarecrow Press. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-8108-4914-3.

Miłosz often emphasized his Lithuanian origins

- ↑ Irena Grudzińska-Gross (24 November 2009). Czesław Miłosz and Joseph Brodsky: fellowship of poets. Yale University Press. p. 291. ISBN 978-0-300-14937-1.

...The "true" Poles reminded the nation of Milosz's Lithuanian origin, his religious unorthodoxy, and his leftist past

- ↑ Encyclopedia of World Biography, Volume 11, pg. 40

- ↑ Robinson Jeffers, Dimensions of a poet, pg. 177

- ↑ Brus, Anna (2009). "Szymon Syruć". Polski Słownik Biograficzny. 46. Polska Akademia Nauk & Polska Akademia Umiejętności. p. 314.

- ↑ Anderson, Raymond H. (15 August 2004). "Czeslaw Milosz, Poet and Nobelist Who Wrote of Modern Cruelties, Dies at 93". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ↑ "In Memoriam". University of California. Archived from the original on 16 February 2008. Retrieved 17 March 2008.

Miłosz would always place emphasis upon his identity as one of the last citizens of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, a place of competing and overlapping identities. This stance – not Polish enough for some, not Lithuanian to others – would give rise to controversies that have not ceased with his death in either country.

- 1 2 (in Lithuanian) "Išėjus Česlovui Milošui, Lietuva neteko dalelės savęs". Mokslo Lietuva (Scientific Lithuania) (in Lithuanian). Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 16 October 2007.

- ↑ Aušra Paulauskienė: Lost and found: the discovery of Lithuania in American fiction. Rodopi 2007, pg. 24

- ↑ Marech, Rona (15 August 2004). "CZESLAW MILOSZ 1911–2004". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 20 March 2008.

- ↑ Czeslaw Milosz (4 April 2006). Selected Poems: 1931–2004 (Biographical note). HarperCollins. p. 261. ISBN 978-0-06-018867-2. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- ↑ Haven, Cynthia L., "'A Sacred Vision': An Interview with Czesław Miłosz", in Haven, Cynthia L. (ed.), Czesław Miłosz: Conversations. University Press of Mississippi, 2006, p. 145.

- 1 2 Between Anxiety and Hope: The Poetry and Writing of Czeslaw Milosz by Edward Możejko. University of Alberta Press, 1988. pp 2f.

- ↑ "Czeslaw Milosz, a Polish émigré poet, died on August 14th, aged 93". The Economist. 14 August 2004. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

In pre-war Poland Mr Milosz felt stifled by the prevailing Catholic-nationalist ethos; he was sacked from a Polish radio station for being too pro-Lithuanian.

- 1 2 Enda O'Doherty. "Apples at World's End". Dublin Review of Books. Retrieved 5 June 2014.

- ↑ "The Year of Czesław Miłosz" (PDF). Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies. August 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 September 2013.

- ↑ Milosz, Czeslaw (1953). The Captive Mind. Poland: Instytut Literacki. p. 169.

- ↑ Czesław Miłosz – his activity to save Jews' lives during the Holocaust, at Yad Vashem website.

- ↑ "Czesław Miłosz (1911–2011)". Leksykon Lublin. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- ↑ Cynthia L. Haven (2006). Czesław Miłosz: Conversations. Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. 206. ISBN 978-1-57806-829-6.

- ↑ Eric Thomas Chester (26 June 1995). Covert Network: Progressives, the International Rescue Committee, and the CIA. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 72–73. ISBN 978-0-7656-3495-5.

- ↑ Segel, Harold B. (14 June 1981). "Czeslaw Milosz And the Laurels of Literature". The Washington Post. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- ↑ Shapiro, Harvey (2 December 2001). "The Durable Czeslaw Milosz". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 July 2018.

- 1 2 "Czeslaw Milosz – Biographical". nobelprize.org (Nobel Prize Media). Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- ↑ Merriman, John; Winter, Jay (2006). "Milosz, Czeslaw (1911–2004)" in Europe Since 1914: Encyclopedia of the Age of War and Reconstruction, vol. 3. Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 1765–66. ISBN 0684313707.

- ↑ "Czesław Miłosz Interviewed by Robert Faggen", The Paris Review No. 133 (Winter 1994).

- ↑ Andreas Dorschel, 'Es ist eine Lust zu beichten', Süddeutsche Zeitung nr. 192 (20 August 2004), p. 14.

- ↑ Photos from Miłosz's funeral in Krakow, miloszinstitute.com. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- ↑ Agnieszka Tennant. "The Poet Who Remembered – Poland (mostly) honors Czeslaw Miłosz upon his death". booksandculture.com.

- ↑ Irena Grudzińska-Gross (2009). Czeslaw Milosz and Joseph Brodsky. Yale University Press. p. 289. ISBN 978-0-300-14937-1. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- ↑ conference on Miłosz and America Archived 4 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine., beinecke.library.yale.edu. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- ↑ Czesław Miłosz Papers

Further reading

- Zagajewski, Adam, editor (2007) Polish Writers on Writing featuring Czeslaw Milosz. Trinity University Press

- Faggen, Robert, editor (1996) Striving Towards Being: The Letters of Thomas Merton and Czesław Miłosz. Farrar Straus & Giroux

- Haven, Cynthia L., editor (2006) Czeslaw Milosz: Conversations. University Press of Mississippi ISBN 1-57806-829-0

- Haven, Cynthia L., editor (2011) An Invisible Rope: Portraits of Czesław Miłosz. Ohio University Press. ISBN-10: 0804011338 ISBN-13: 978-0804011334

- Miłosz, Czesław (2006) New and Collected Poems 1931–2001. Penguin Modern Classics Poetry ISBN 0-14-118641-0 (posthumous collection)

- Miłosz, Czesław (2010) Proud To Be A Mammal: Essays on War, Faith and Memory. Penguin Translated Texts ISBN 0-14-119319-0 (posthumous collection)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Czesław Miłosz. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Czesław Miłosz |

Profiles

- Works by Czesław Miłosz at Open Library

- 1980 Nobel Prize in Literature (official site). Retrieved 2010-08-04

- Profile at the American Academy of Poets. Retrieved 2010-08-04

- Profile and works at the Poetry Foundation

Articles

- Profile at Culture PL. Retrieved 2011-03-17

- Robert Faggen (Winter 1994). "Czeslaw Milosz, The Art of Poetry No. 70". The Paris Review.

- Interview with Nathan Gardels for the New York Review of Books, February 1986. Retrieved 2010-08-04

- Georgia Review 2001. Retrieved 2010-08-04

- Obituary The Economist. Retrieved 2010-08-04

- Obituary New York Times. Retrieved 2010-08-04

- Biography and selected works listing. The Book Institute. Retrieved 2010-08-04

- Czeslaw Milosz Papers. General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

Biographies, memoirs, photographs

- Czesław Miłosz 1911–2004 – The life („Gazeta.pl”)

- My Milosz – the memories of Nobel Prize winners, including Seamus Heaney and Maria Janion

- Genealogia Czesława Miłosza w: M.J. Minakowski, Genealogy descendants of the Great Diet

- Barbara Gruszka-Zych, Mój Poeta – osobiste wspomnienia o Czesławie Miłoszu, VIDEOGRAF II, ISBN 978-83-7183-499-8

- Milosz – the centenary since the birth

Bibliography

- Presentation of the subject-object

- Bibliography in question 1981–2010 (journal articles in chronological order, the title)

- Translations into other languages

- Bibliography in question in the choice in alphabetical order

- Bibliografia subject-object

- Bibliography subject-object

- Bibliografiasubject-object in choosing

- Polskie wydawnictwa niezależne 1976–1989. Printed compact Milosz

Polemical articles

- Błotne kąpiele artykuł nt. wybiórczych cytatów z Miłosza w twórczości Waldemara Łysiaka i Jerzego R. Nowaka

- Czesław Miłosz – lewy profil – esej Jacka Trznadla

- "Były poputczik Miłosz", krytyczny tekst Sergiusza Piaseckiego (Wiadomości 1951, nr 44)