Cushitic languages

| Cushitic | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | Northeast Africa |

| Linguistic classification |

Afro-Asiatic

|

| Proto-language | Proto-Cushitic |

| Subdivisions |

|

| ISO 639-2 / 5 | cus |

| Glottolog | cush1243[1] |

| |

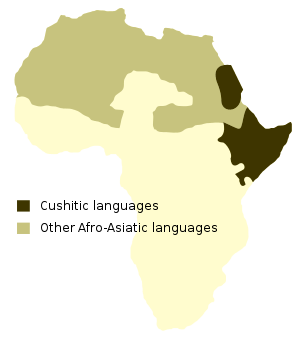

The Cushitic languages are a branch of the Afroasiatic language family. They are spoken primarily in the Horn of Africa (Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia and Somalia), as well as the Nile Valley (Sudan and Egypt), and parts of the African Great Lakes region (Tanzania and Kenya).

The Cushitic languages with the greatest number of total speakers are Oromo (41 million),[2] Somali (16.2 million),[3] Beja (3.2 million),[4] Sidamo (3 million),[5] and Afar (2 million).[6] Oromo is the working language of the Oromia Region in Ethiopia.[7] Somali is one of two official languages of Somalia, and as such is the only Cushitic language accorded official language status at the country level.[8] It also serves as a language of instruction in Djibouti,[9] and as the working language of the Somali Region in Ethiopia.[7] Beja, Afar, Blin and Saho, the languages of the Cushitic branch of Afroasiatic that are spoken in Eritrea, are languages of instruction in the Eritrean elementary school curriculum.[10] The constitution of Eritrea also recognizes the equality of all natively spoken languages.[11] Additionally, Afar is a language of instruction in Djibouti,[9] as well as the working language of the Afar Region in Ethiopia.[7]

The phylum was first designated as Cushitic around 1858.[12] Historical linguistic analysis and archaeogenetics indicate that the languages spoken in the ancient Kerma culture of what is now southern Egypt and northern Sudan,[13][14] as well as those spoken in the Savanna Pastoral Neolithic culture of the Great Lakes region, likely belonged to the Cushitic branch of the Afroasiatic family.[15]

Composition

The Cushitic languages are usually considered to include the following branches:[16]

- North Cushitic (Beja)

- Central Cushitic (Agaw languages)

- East Cushitic

- South Cushitic

This classification has not been without contention, and many other classifications have been proposed over the years.

| Greenberg (1963)[17] | Hetzron (1980)[18] | Fleming (post-1981) | Orel & Stobova (1995) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Diakonoff (1996) | Militarev (2000) | Tosco (2000)[19] | Ehret (2011)[20] |

(Does not include Omotic) |

|

|

|

Divergent languages

Beja is part of the Cushitic branch of the Afroasiatic family, constituting the only member of the Northern Cushitic subgroup. As such, Beja contains a number of linguistic innovations that are unique to it, as is also the situation with the other subgroups of Cushitic (e.g. idiosyncratic features in Agaw or Central Cushitic).[21] Hetzron (1980) argues that Beja therefore may comprise an independent branch of the Afroasiatic family.[22] However, this suggestion has been largely ignored by the linguistic community. The characteristics of Beja that differ from those of other Cushitic languages are instead generally acknowledged as normal branch variation.[21] These unique features are also attributed to the fact that the Beja language, along with the Saho-Afar dialect cluster, are the most conservative forms of Cushitic speech.[23]

Joseph Halévy (1873) identified linguistic similarities shared between Beja and other neighboring Cushitic languages (viz. Afar, Agaw, Oromo and Somali). Leo Reinisch subsequently grouped Beja with Saho-Afar, Somali and Oromo in a Lowland Cushitic sub-phylum, representing one half of a two-fold partition of Cushitic. Moreno (1940) proposed a bipartite classification of Beja similar to that of Reinisch, but lumped Beja with both Lowland Cushitic and Central Cushitic. Around the same period, Enrico Cerulli (c. 1950) asserted that Beja constituted an independent sub-group of Cushitic. During the 1960s, Archibald N. Tucker (1960) posited an orthodox branch of Cushitic that comprised Beja, East Cushitic and Agaw, and a fringe branch of Cushitic that included other languages in the phylum. Although also similar to Reinisch's paradigm, Tucker's orthodox-fringe dichotomy was predicated on a different typological approach. Andrzej Zaborski (1976) suggested, on the basis of genetic features, that Beja constituted the only member of the North Cushitic sub-phylum.[24] Due to its linguistic innovations, Robert Hetzron (1980) argued that Beja may constitute an independent branch of the Afroasiatic family.[25] Hetzron's suggestion was arrived at independently,[26] and was criticized or rejected by other linguists (Zaborski 1984[27] & 1997; Tosco 2000;[24] Morin 2001[28]). Appleyard (2004) later also demonstrated that the innovations in Beja, which Hetzron had identified, were centered on a typological argument involving a presumed change in syntax and also consisted of only five differing Cushitic morphological features. Marcello Lamberti (1991) elucidated Cerulli's traditional classification of Beja, juxtaposing the language as the North Cushitic branch alongside three other independent Cushitic sub-phyla, Lowland Cushitic, Central Cushitic and Sidama. Didier Morin (2001) assigned Beja to Lowland Cushitic on the grounds that the language shared lexical and phonological features with the Afar and Saho idioms, and also because the languages were historically spoken in adjacent speech areas. However, among linguists specializing in the Cushitic languages, Cerulli's traditional paradigm is accepted as the standard classification for Beja.[24]

There are also a few poorly-classified languages, including Yaaku, Dahalo, Aasax, Kw'adza, Boon, the Cushitic element of Mbugu (Ma'a) and Ongota. There is a wide range of opinions as to how the languages are interrelated.[29]

The positions of the Dullay languages and of Yaaku are uncertain. They have traditionally been assigned to an East Cushitic branch along with Highland (Sidamic) and Lowland East Cushitic. However, Hayward thinks that East Cushitic may not be a valid node and that its constituents should be considered separately when attempting to work out the internal relationships of Cushitic.[29]

The Afroasiatic identity of Ongota is also broadly questioned, as is its position within Afroasiatic among those who accept it, because of the "mixed" appearance of the language and a paucity of research and data. Harold C. Fleming (2006) proposes that Ongota is a separate branch of Afroasiatic.[30] Bonny Sands (2009) thinks the most convincing proposal is by Savà and Tosco (2003), namely that Ongota is an East Cushitic language with a Nilo-Saharan substratum. In other words, it would appear that the Ongota people once spoke a Nilo-Saharan language but then shifted to speaking a Cushitic language while retaining some characteristics of their earlier Nilo-Saharan language.[31][32]

Hetzron (1980:70ff)[33] and Ehret (1995) have suggested that the South Cushitic languages ("Rift") are a part of Lowland East Cushitic, the only one of the six groups with much internal diversity.

Cushitic was formerly seen as also including the Omotic languages, then called West Cushitic. However, this view has been abandoned. Omotic is generally agreed to be an independent branch of Afroasiatic, primarily due to the work of Harold C. Fleming (1974) and Lionel Bender (1975); some linguists like Paul Newman (1980) challenge Omotic's classification within the Afroasiatic family itself.

Extinct languages

A number of extinct populations are thought to have spoken Afroasiatic languages of the Cushitic branch. According to Peter Behrens (1981) and Marianne Bechaus-Gerst (2000), linguistic evidence indicates that the peoples of the Kerma Culture in present-day southern Egypt and northern Sudan spoke Cushitic languages.[34][14] The Nilo-Saharan Nobiin language today contains a number of key pastoralism related loanwords that are of proto-Highland East Cushitic origin, including the terms for sheep/goatskin, hen/cock, livestock enclosure, butter and milk. This in turn suggests that the Kerma population – which, along with the C-Group culture, inhabited the Nile Valley immediately before the arrival of the first Nubian speakers – spoke Afroasiatic languages.[34]

Additionally, historiolinguistics indicate that the makers of the Savanna Pastoral Neolithic (Stone Bowl Culture) in the Great Lakes area likely spoke South Cushitic languages.[35] Christopher Ehret (1998) proposes that among these languages were the now extinct Tale and Bisha languages, which were identified on the basis of loanwords.[36] Ancient DNA analysis of a Savanna Pastoral Neolithic fossil excavated at the Luxmanda site in Tanzania likewise found that the specimen carried a large proportion of ancestry related to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic culture of the Levant, similar to that borne by modern Afroasiatic-speaking populations inhabiting the Horn of Africa. This suggests that the Savanna Pastoral Neolithic culture bearers may have been Cushitic speakers, who were gradually absorbed by neighboring hunter-gatherer communities in the lacustrine region.[15]

Reconstruction

Proto-Cushitic has been reconstructed by Ehret (1987).[37]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Cushitic". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ "Population and Housing Census of Ethiopia (2007)". Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia. p. 118. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- ↑ "Somali". Ethnologue. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- ↑ "Bedawiyet". Ethnologue. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- ↑ "Sidamo". Ethnologue. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- ↑ "Afar". Ethnologue. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Constitution of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia" (PDF). Government of Ethiopia. pp. 2 & 16. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

Members of the Federation may by law determine their respective working languages.[...] Member States of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia are the Following: 1) The State of Tigray 2) The State of Afar 3) The State of Amhara 4) The State of Oromia 5) The State of Somalia 6) The State of Benshangul/Gumuz 7) The State of the Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples 8) The State of the Gambela Peoples 9) The State of the Harari People

- ↑

- "The Constitution of the Somali Republic (as amended up to October 12, 1990)" (PDF). Government of Somalia. p. 2. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

Article 4 (Official language) The official languages of the state shall be Somali and Arabic.

- "The Federal Republic of Somalia Provisional Constitution" (PDF). Government of Somalia. p. 10. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

Article 5. Official Languages[...] The official language of the Federal Republic of Somalia is Somali (Maay and Maxaa-tiri), and Arabic is the second language.

- "The Transitional Federal Charter of the Somali Republic" (PDF). Government of Somalia. p. 5. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

ARTICLE 7 LANGUAGES. 1. The official languages of the Somali Republic shall be Somali (Maay and Maxaatiri) and Arabic.

- "Somalia - Languages". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

Somali (official, according to the 2012 Transitional Federal Charter), Arabic (official, according to the 2012 Transitional Federal Charter), Italian, English

- "The Constitution of the Somali Republic (as amended up to October 12, 1990)" (PDF). Government of Somalia. p. 2. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- 1 2

- "Journal Officiel de la République de Djibouti - Loi n°96/AN/00/4èmeL portant Orientation du Système Educatif Djiboutien" (PDF). Government of Djibouti. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

Article 5 : L’Education et la Formation sont dispensées dans les langues officielles et dans les langues nationales. Un Décret pris en Conseil des Ministres fixe les modalités de l’enseignement en français, en arabe, en Afar et en Somali.

- "Djibouti in Brief" (PDF). Chamber of Commerce of Djibouti. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

Languages: Arab, French (official) Afar, Somali (national)

- "Journal Officiel de la République de Djibouti - Loi n°96/AN/00/4èmeL portant Orientation du Système Educatif Djiboutien" (PDF). Government of Djibouti. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- ↑ Graziano Savà, Mauro Tosco (January 2008). ""Ex Uno Plura": the uneasy road of Ethiopian languages toward standardization". International Journal of the Sociology of Language. 2008 (191): 117. doi:10.1515/ijsl.2008.026. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

the following other languages have been introduced in the elementary school curriculum[...] ‘Afar, Beja, Bilin, and Saho (languages of the Cushitic branch of Afroasiatic)

- ↑ "The Constitution of Eritrea" (PDF). Government of Eritrea. p. 524. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

The equality of all Eritrean languages is guaranteed

- ↑ Lipiński, Edward (2001). Semitic Languages: Outline of a Comparative Grammar Volume 80 of Orientalia Lovaniensia analecta. Peeters Publishers. p. 21. ISBN 9042908157. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- ↑ Bechaus-Gerst, Marianne; Blench, Roger (2014). Kevin MacDonald, ed. The Origins and Development of African Livestock: Archaeology, Genetics, Linguistics and Ethnography - "Linguistic evidence for the prehistory of livestock in Sudan" (2000). Routledge. p. 453. ISBN 1135434166. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- 1 2 Behrens, Peter (1986). Libya Antiqua: Report and Papers of the Symposium Organized by Unesco in Paris, 16 to 18 January 1984 - "Language and migrations of the early Saharan cattle herders: the formation of the Berber branch". Unesco. p. 30. ISBN 9231023764. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- 1 2 Skoglund, Pontus; Thompson, Jessica C.; Prendergast, Mary E.; Mittnik, Alissa; Sirak, Kendra; Hajdinjak, Mateja; Salie, Tasneem; Rohland, Nadin; Mallick, Swapan (2017-09-21). "Reconstructing Prehistoric African Population Structure". Cell. 171 (1): 59–71.e21. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.049. ISSN 0092-8674. PMC 5679310. PMID 28938123.

- ↑ Appleyard, David (2012). "Cushitic". In Edzard, Lutz. Semitic and Afroasiatic: Challenges and Opportunities. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 200. ISBN 9783447066952.

- ↑ Greenberg, Joseph (1963). The Languages of Africa. Bloomington: Indiana University. pp. 48–49.

- ↑ Hetzron, Robert (1980). "The limits of Cushitic". Sprache und Geschichte in Afrika. 2: 7–126.

- ↑ Tosco, Mauro (November 2000). "Cushitic Overview". Journal of Ethiopian Studies. 33 (2): 108. JSTOR 41966109.

- ↑ Ehret, Christopher (2011). History and the Testimony of Language. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 138, 147. ISBN 9780520262041.

- 1 2 Zaborski, Andrzej (1988). Fucus - "Remarks on the Verb in Beja". John Benjamins Publishing. p. 491. ISBN 902723552X. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- ↑ Frawley (ed.), William (2003). International Encyclopedia of Linguistics: AAVE-Esperanto. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. p. 405. ISBN 0195139771. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- ↑ Allan R. Bomhard, John C. Kerns (1994). The Nostratic Macrofamily: A Study in Distant Linguistic Relationship. Walter de Gruyter. p. 24. ISBN 3110139006. Retrieved 26 September 2017.

- 1 2 3 Vanhove, Martine. "North-Cushitic". LLACAN, CNRS-INALCO, Université Sorbonne Paris-Cité. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ↑ Hetzron, Robert (1980). "The limits of Cushitic". Sprache und Geschichte in Afrika. 2: 7–126.

- ↑ Ekkehard Wolff, Hilke Meyer-Bahlburg (1983). Studies in Chadic and Afroasiatic linguistics: papers from the International Colloquium on the Chadic Language Family and the Symposium on Chadic within Afroasiatic, at the University of Hamburg, September 14-18, 1981. H. Buske. p. 23. ISBN 3871186074. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- ↑ Zaborski, Andrzej (1984). "Remarks on the Genetic Classification and Relative Chronology of the Cushitic Languages". In James Bynon. Current Progress in Afro-Asiatic Linguistics. Third International Hamito-Semitic Congress. pp. 127–135.

- ↑ Morin, Didier (2001). "Bridging the gap between Northern and Eastern Cushitic". In Zaborski, Andrzej. New Data and New Methods in Afroasiatic Linguistics. Robert Hetzron in memoriam. Otto Harassowitz. pp. 117–124.

- 1 2 Richard Hayward, "Afroasiatic", in Heine & Nurse, 2000, African Languages

- ↑ Harrassowitz Verlag – The Harrassowitz Publishing House

- ↑ Savà, Graziano; Tosco, Mauro (2003). "The classification of Ongota". In Bender, M. Lionel; et al. Selected comparative-historical Afrasian linguistic studies. LINCOM Europa.

- ↑ Sands, Bonny (2009). "Africa's Linguistic Diversity". Language and Linguistics Compass. 3 (2): 559–580. doi:10.1111/j.1749-818x.2008.00124.x.

- ↑ Robert Hetzron, "The Limits of Cushitic", Sprache und Geschichte in Afrika 2. 1980, 7–126.

- 1 2 Bechaus-Gerst, Marianne; Blench, Roger (2014). Kevin MacDonald, ed. The Origins and Development of African Livestock: Archaeology, Genetics, Linguistics and Ethnography – "Linguistic evidence for the prehistory of livestock in Sudan" (2000). Routledge. pp. 453–457. ISBN 1135434166. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- ↑ Ambrose, Stanley H. (1984). From Hunters to Farmers: The Causes and Consequences of Food Production in Africa – "The Introduction of Pastoral Adaptations to the Highlands of East Africa". University of California Press. pp. 234 & 223. ISBN 0520045742. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ↑ Roland Kießling, Maarten Mous & Derek Nurse. "The Tanzanian Rift Valley area". Maarten Mous. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ↑ Ehret, Christopher. 1987. Proto-Cushitic reconstruction. In Sprache und Geschichte in Afrika 8: 7-180. University of Cologne.

References

- Ethnologue on the Cushitic branch

- Bender, Marvin Lionel. 1975. Omotic: a new Afroasiatic language family. Southern Illinois University Museum series, number 3.

- Bender, M. Lionel. 1986. A possible Cushomotic isomorph. Afrikanistische Arbeitspapiere 6:149–155.

- Fleming, Harold C. 1974. Omotic as an Afroasiatic family. In: Proceedings of the 5th annual conference on African linguistics (ed. by William Leben), p 81-94. African Studies Center & Department of Linguistics, UCLA.

- Roland Kießling & Maarten Mous. 2003. The Lexical Reconstruction of West-Rift Southern Cushitic. Cushitic Language Studies Volume 21

- Lamberti, Marcello. 1991. Cushitic and its classification. Anthropos 86(4/6):552-561.

- Newman, Paul. 1980. The Classification of Chadic within Afroasiatic. Universitaire Pers.

- Zaborski, Andrzej. 1986. Can Omotic be reclassified as West Cushitic? In Gideon Goldenberg, ed., Ethiopian Studies: Proceedings of the 6th International Conference, pp. 525–530. Rotterdam: Balkema.

- Reconstructing Proto-Afroasiatic (Proto-Afrasian): Vowels, Tone, Consonants, and Vocabulary (1995) Christopher Ehret