Culross

Culross

| |

|---|---|

|

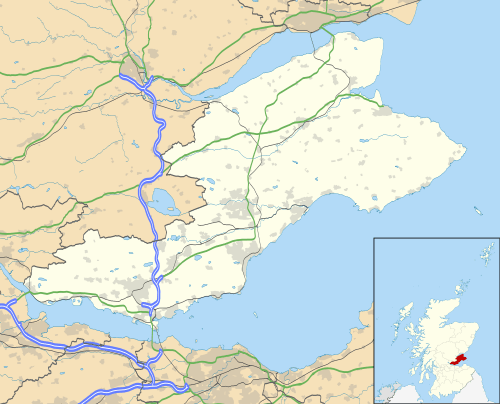

Culross and the Firth of Forth | |

Culross Culross shown within Fife | |

| Population | 395 [1] |

| Council area | |

| Lieutenancy area | |

| Country | Scotland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Police | Scottish |

| Fire | Scottish |

| Ambulance | Scottish |

| EU Parliament | Scotland |

| UK Parliament | |

| Scottish Parliament | |

Culross (/ˈkurəs/) (Gaelic: Cuileann Ros) is a village and former royal burgh, and parish, in Fife, Scotland.

According to the 2006 estimate, the village has a population of 395.[1] Originally, Culross served as a port city on the Firth of Forth and is believed to have been founded by Saint Serf during the 6th century.

The civil parish had a population of 4,348 in 2011.[2]

Founding legend

A legend states that when the British princess (and future saint) Teneu, daughter of the king of Lothian, became pregnant before marriage, her family threw her from a cliff. She survived the fall unharmed, and was soon met by an unmanned boat. She knew she had no home to go to, so she got into the boat; it sailed her across the Firth of Forth to land at Culross where she was cared for by Saint Serf; he became foster-father of her son, Saint Kentigern or Mungo.[3][4][5][6][7]

Industry

During the 16th and 17th centuries, the town was a centre of the coal mining industry.[6][7] Sir George Bruce of Carnock, who built the splendid 'Palace' of Culross and whose elaborate family monument stands in the north transept of the Abbey church, established a coal mine at Culross in 1575 and in 1595 constructed the Moat Pit[8] by which it became the first coal mine in the world to extend under the sea. The mine worked what is now known as the Upper Hirst coal seam, with ingenious contrivances to drain the constant leakage from above. This mine was considered one of the marvels of the British Isles in the early 17th century, described by one visitor, John Taylor, The Water Poet, as "a wonder ... an unfellowed and unmatchable work",[9] until the Moat Pit was destroyed in a storm on 30 March 1625.[8][10]

Culross' secondary industry was salt panning.[11]:9-10 There was a considerable export trade by sea in the produce of these industries and the prevalence of red roof tiles in Culross and other villages in Fife is thought to be a direct result of collier ships returning to Culross with Dutch roof tiles as ballast. The town was also known for its monopoly on the manufacture of 'girdles', i.e. flat iron plates for baking over an open fire.[12][6][7]

In the late 18th century, Archibald Cochrane, 9th Earl of Dundonald established kilns for extracting coal tar using his patented method.[11]:12-13

The town's role as a port declined from the 18th century, and by Victorian times it had become something of a 'ghost town'. The harbour was filled in and the sea cut off by the coastal railway line in the second half of the 19th century (though the outer harbour has recently been restored by a local group).

Heritage

During the 20th century, it became recognised that Culross contained many unique historical buildings and the National Trust for Scotland has been working on their preservation and restoration since the 1930s.[13]

Notable buildings in the burgh include Culross Town House, formerly used as a courthouse and prison, the 16th century Culross Palace, 17th century Study, and the remains of the Cistercian house of Culross Abbey, founded 1217.[14][13][15] The tower, transepts and choir of the Abbey Church remain in use as the parish church, while the ruined claustral buildings are cared for by Historic Environment Scotland.[16] Just outside the town is the 18th-century Dunimarle Castle, built by the Erskine family to supersede a medieval castle.[17]

Thomas Cochrane, 10th Earl of Dundonald spent much of his early life in Culross, where his family had an estate.[18] There is now a bust in his honour outside the Culross Town House.[19] He was the first Vice Admiral of Chile.[20]

The war memorial was erected in 1921 to a design by Sir Robert Lorimer.[21]

Administration

Prior to the 1890s, the parish of Culross formed an exclave of Perthshire.[22] It is within the Dunfermline and West Fife Westminster Parliamentary constituency.[23]

Culross as a location for filming

Several motion pictures have used Culross as a filming location, including Kidnapped (1971),[24] The Little Vampire (2000),[25] A Dying Breed (2007),[26] The 39 Steps (2008),[27] and Captain America: The First Avenger (2011).[28] In September 2013, the Starz television series, Outlander, started filming in Culross for its premiere in August 2014.[29]

Notable people

- George Bruce of Carnock (1550-1625), Lord Bruce

- Elizabeth Melville, "Lady Culross" (c.1578 - c.1640), Scotland's earliest known published female poet

- Stewart McPherson (1822-1892), recipient of the Victoria Cross

- Rev Robert Pont (1525-1606) radical church figure during the Reformation, five times Moderator of the Church of Scotland

- Jackie Sinclair (1943-2010), Scottish international footballer

Twin towns and sister cities

Culross is twinned with Veere in the Netherlands, which was formerly the port through which its export goods entered the Low Countries.[30]

References

- 1 2 "Population Estimates for Towns and Villages in Fife" (PDF). Fife Council. March 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 February 2010. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- ↑ Census of Scotland 2011, Table KS101SC – Usually Resident Population, publ. by National Records of Scotland. Web site http://www.scotlandscensus.gov.uk/ retrieved March 2016. See "Standard Outputs", Table KS101SC, Area type: Civil Parish 1930

- ↑ "Mungo, the saint from Culross".

- ↑ "Scotland's Pilgrim Journeys".

- ↑ "University of Glasgow :: Story :: The Coat of Arms".

- 1 2 3 "St Mungo and his mysterious deeds".

- 1 2 3 Keay, John and Julia (1994). Collins Encyclopedia of Scotland (1st ed.). London: Collins. p. 205. ISBN 0 00 255082 2.

- 1 2 Adamson, Donald (2008). "A Coal Mine in the Sea: Culross and the Moat Pit". Scottish Archaeological Journal. 30 (1–2): 161–199. JSTOR 27917615.

- ↑ Taylor, John. "The Penniless Pilgrimage" (PDF). Renascence Editions. pp. 22–24. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- ↑ "Culross". Undiscovered Scotland. 2002–2009. Retrieved 8 Sep 2009.

- 1 2 Sugden, J (September 2012). "ARCHIBALD, 9th EARL OF DUNDONALD: AN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ENTREPRENEUR". Scottish Economic & Social History. Edinburgh University Press. 8 (1). doi:10.3366/sesh.1988.8.8.8.

- ↑ "Hearth and Home". Fife Folk Museum. Archived from the original on 19 November 2008. Retrieved 2009-04-05.

- 1 2 Harvie, Christopher (2014). Scotland: A Short History. Oxford University Press. p. 95. ISBN 9780198714880.

- ↑ Keay, John and Julia (1994). Collins Encyclopedia of Scotland (1st ed.). London: Collins. p. 206. ISBN 0 00 255082 2.

- ↑ Douglas, William (1925). "Culross Abbey and its Charters" (PDF). Archaeology Data Service. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- ↑ "Culross Abbey".

- ↑ "Dunimarle Castle: Site History". Historic Environment Scotland. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ↑ Cordingly, By David. "The real master and commander".

- ↑ "Cochrane was Britain's greatest frigate captain".

- ↑ Hickman, Kennedy. "Napoleonic Wars: Admiral Lord Thomas Cochrane". Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ↑ Dictionary of Scottish Architects: Robert Lorimer

- ↑ Taylor, Simon; Gilbert Markus (2006). The Place-Names of Fife, Volume One. Shaun Tyas. p. 223. ISBN 1-900289-77-6.

The parish of Culross, along with its neighbouring parish of Tulliallan, also Dunblane Diocese, formed a detached part of the earldom, later the stewartry, of Strathearn, which explains why both were in a detached part of Perthshire until 1891, when they became part of Fife.

- ↑ "Boundary Commission for Scotland - Maps - UK Parliament constituencies 2005 onwards". Archived from the original on 2013-05-04.

- ↑ Kidnapped (1971) on IMDb

- ↑ "The Little Vampire - Culross". Scotland: the Movie Location Guide. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ↑ A Dying Breed (2007) on IMDb

- ↑ The 39 Steps (2008) on IMDb

- ↑ Captain America: The First Avenger (2011) on IMDb

- ↑ Ferguson, Brian (23 August 2014). "Outlander could run for five years says Moore". The Scotsman. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ↑ "The Scottish Staple at Veere". Archived from the original on 2010-12-04. Retrieved 2009-02-01.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Culross. |

- Culross community site at Fife Council

- Entry in A Topographical Dictionary of Scotland (1846)

- Culross Arts and Music Festival

- Engraving of Culross in 1693 by John Slezer at National Library of Scotland