Cretoxyrhina

| Cretoxyrhina | |

|---|---|

.png) | |

| Fossil skeletons of C. mantelli (B, C) and C. sp. (A, D) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Order: | Lamniformes |

| Family: | †Cretoxyrhinidae |

| Genus: | †Cretoxyrhina Glikman, 1958 |

| Type species | |

| †Cretoxyrhina mantelli Agassiz, 1843 | |

| Species | |

| Synonyms | |

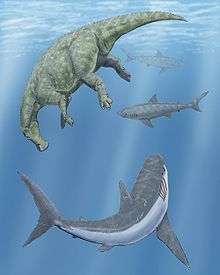

Cretoxyrhina is an extinct genus of large mackerel shark that lived from the Late Albian to Campanian during the Late Cretaceous period. The common name of the type species C. mantelli is the Ginsu shark, first popularized in reference to its theoretical feeding methods being comparable to that of a modern Ginsu knife.[3] Cretoxyrhina was one the largest sharks of its time, reaching lengths of up to 7 metres (23 ft)[4] and was a chief predator in its ecosystem, preying on a variety of marine animals, including marine reptiles like mosasaurs and plesiosaurs, and other large fish.

Cretoxyrhina fossils are cosmopolitan and have been found world wide, being most frequent in the Western Interior Seaway area of North America.[5] It is one of the most well-understood extinct sharks to date, with multiple examples of exquisitely preserved skeletons having been discovered. Cretoxyrhina is very similar to the modern great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) in terms of morphological features, body length/form, and ecological role.[4]

Taxonomy

Naming

Cretoxyrhina is an assemblage of the word creto (short for Cretaceous) prefixed to the genus Oxyrhina, which is derived from the Ancient Greek ὀξύς (oxús, “sharp”) and ῥίς (rhís, “nose”). When put together they would mean "Cretaceous sharp-nose", although in reality Cretoxyrhina is believed to have a rather blunt snout.[6] The type species name mantelli translates to "from Mantell", which could possibly be an honor to English paleontologist Gideon Mantell. The species name denticulata is derived from the Latin denticulus (small tooth) and āta (to have), meaning "having small teeth" together. This is a reference to the appearance of lateral cusplets in most of the teeth in C. denticulata. The species vraconensis derived from the word vracon and the Latin ensis (from [location]), meaning "from Vracon".

Phylogeny and Evolution

In terms of morphological features including body size and shape, skeletal anatomy, and ecological role, Cretoxyrhina is most similar to the modern great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias). However, the two sharks are not closely related and their similarities are a result of convergent evolution.[4] Phylogenic studies through molecular genetics conducted by Shimada (2005) made results showing that Cretoxyrhina could be congeneric with the modern thresher sharks (Genus Alopias). However, due to the uncertainty of the incomplete code for Cretoxyrhina, the study also stated that the results are premature and may be artifact, recommending that Cretoxyrhina is kept within the family Cretoxyrhinidae.[7]Another possible model for Cretoxyrhina's evolution, proposed by Diedrich (2014) , suggests that C. mantelli is congeneric with the genus Isurus and is part of an extended Isurus lineage beginning as far the Aptian stage in the Early Cretaceous. According to this model, the Isurus lineage is initiated by Isurus appendiculatus (Otodus appendiculatus), which evolved into Isurus denticulatus in the Mid-Cenomanian, which then evolved into Isurus mantelli (Cretoxyrhina mantelli) at the beginning of the Coniacian, and then evolved into Isurus schoutedenti during the Paleocene, which in turn evolved into Isurus praecursor, where the rest of the Isurus lineage continues. The study insists that the long absence of C. mantelli fossils in post-Campanian is not a result of extinction, but merely a gap in the fossil record.[8] However, this proposal has been rejected by other paleontologists.

Biology

Cretoxyrhina is among the most well-understood fossil sharks to date, with several preserved specimens having revealed a great deal of insight about its physical features and lifestyle. The teeth of C. mantelli were up to 7 centimetres (3 in) long,[9] curved, and smooth-edged, with a thick enamel coating. The jaws of Cretoxyrhina contained up to seven rows of teeth, with 34 teeth in each row of its upper jaw and 36 in each row of its lower jaw.[10] Cretoxyrhina mantelli grew up to 7 metres (23 ft) long,[4] and exceeded the extant great white shark, Carcharodon carcharias, in size.

History

This shark was first identified by the famous Swiss Naturalist Louis Agassiz, in 1843, as Cretoxyhrina mantelli. However, the most complete specimen of this shark was discovered in 1890, by fossil hunter Charles H. Sternberg, who published his findings in 1907. The specimen comprised a nearly complete associated vertebral column and over 250 associated teeth. This kind of exceptional preservation of fossil sharks is rare, because a shark's skeleton is made of cartilage, which is not prone to fossilization. Charles dubbed the specimen Oxyrhina mantelli. This specimen represented a 6.1-metre-long (20 ft) shark. It was excavated from Hackberry Creek, Gove County, Kansas.[10]

In later years, several other specimens have also been found. One such specimen was discovered in 1891 by George Sternberg, and was stored in a Munich museum. This specimen was also reported to be 6.1 metres (20 ft) long, but was destroyed during a bombing raid on Munich in World War II.[10]

Paleobiology

Cretoxyrhina was the largest shark in its time and was among the chief predators of the seas. Fossil records revealed that it preyed on a variety of marine animals, such as mosasaurs like Tylosaurus,[11] plesiosaurs like Elasmosaurus,[12] bony fish like Xiphactinus,[13] and protostegid turtles like Archelon.[5] There is also an occasion where Cretoxyrhina fed on a Pteranodon, as a bone from the latter has been discovered with the shark's tooth embedded in it.[14] Cretoxyrhina lived in Cenomanian–Campanian seas worldwide, including in the Western Interior Seaway of North America.[15]

See also

References

- ↑ Kenshu Shimada (1997). "Stratigraphic Record of the Late Cretaceous Lamniform Shark, Cretoxyrhina mantelli (Agassiz), in Kansas". Kansas Academy of Science.

- ↑ Mikael Siverson and Johan Lindgren (2005). "Late Cretaceous sharks Cretoxyrhina and Cardabiodon from Montana, USA" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica.

- ↑ Everhart, Mike (2009). "Cretoxyrhina mantelli, the Ginsu Shark".

Since the shark had no common name in the literature, and since it fed by ‘slicing’ up its victim into bite-size pieces, we [paleontologists K. Shimada and M. J. Everhart] decided that the title “Ginsu Shark”, was an appropriate, descriptive (and somewhat humorous) name for this awesome creature.

- 1 2 3 4 Kenshu Shimada (2008). "ONTOGENETIC PARAMETERS AND LIFE HISTORY STRATEGIES OF THE LATE CRETACEOUS LAMNIFORM SHARK, CRETOXYRHINA MANTELLI, BASED ON VERTEBRAL GROWTH INCREMENTS". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

- 1 2 Shimada, Kenshu; Hooks, G. E. (2004). "SHARK-BITTEN PROTOSTEGID TURTLES from the UPPER CRETACEOUS MOOREVILLE CHALK, ALABAMA". Journal of Paleontology. Retrieved 2009-10-02.

- ↑ Kenshu Shimada (1997). "Skeletal Anatomy of the Late Cretaceous Lamniform Shark, Cretoxyrhina mantelli, from the Niobrara Chalk in Kansas". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

- ↑ Kenshu Shimada (2005). "Phylogeny of lamniform sharks (Chondrichthyes: Elasmobranchii) and the contribution of dental characters to lamniform systematics". Paleontological Research.

- ↑ C. G. Diedrich (2014). "Skeleton of the Fossil Shark Isurus denticulatus from the Turonian (Late Cretaceous) of Germany—Ecological Coevolution with Prey of Mackerel Sharks". Paleontology Journal.

- ↑ Everhart, Mike. "Large Sharks in the Western Interior Sea".

- 1 2 3 Everhart, Mike. "A giant Ginsu shark (Cretoxyrhina mantelli Agassiz) From Late Cretaceous Chalk of Kansas".

- ↑ Rothschild, B. M. (2005). "Sharks eating mosasaurs, dead or alive?" (PDF). Netherlands Journal of Geosciences. 21 (4): 335–340. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2009-10-02.

- ↑ Everhart, M. J. (2005). "Bite marks on an elasmosaur (Sauropterygia; Plesiosauria) paddle from the Niobrara Chalk (Upper Cretaceous) as probable evidence of feeding by the lamniform shark, Cretoxyrhina mantelli" (PDF). PalArch's Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Retrieved 2009-10-02.

- ↑ Shimada, Kenshu (1997). "Paleoecological relationships of the Late Cretaceous lamniform shark, Cretoxyrhina mantelli (Agassiz)". Journal of Paleontology. Retrieved 2009-10-02.

- ↑ https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/2018/10/news-sharks-eating-pterosaurs-fossils-cretaceous-paleontology/

- ↑ Shimada, Kenshu; Cumbaa, S. L.; Rooyen, D. V. (2006). "Caudal Fin Skeleton of the LATE CRETACEOUS LAMNIFORM SHARK, CRETOXYRHINA MANTELLI, from the NIOBRARA CHALK OF KANSAS" (PDF). New Mexico Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 2009-10-02.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cretoxyrhina. |

- Fact File from National Geographic

- Mega Beasts: Sea of Killers, video [dead link]