Tylosaurus

| Tylosaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

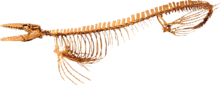

| "Bunker" T. proriger (KUVP 5033) mounted skeleton in the Rocky Mountain Dinosaur Resource Center in Woodland Park, Colorado | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Superfamily: | †Mosasauroidea |

| Family: | †Mosasauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Tylosaurinae |

| Genus: | †Tylosaurus Marsh, 1872 |

| Species | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

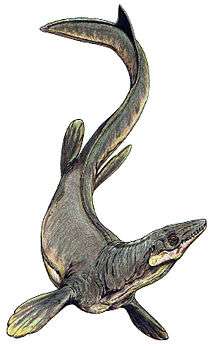

Tylosaurus (Greek τυλος/tylos "protuberance, knob" + Greek σαυρος/sauros "lizard") was a mosasaur, a large, predatory marine lizard closely related to modern monitor lizards and to snakes.

Description

A distinguishing characteristic of Tylosaurus is its elongated, cylindrical premaxilla (snout) from which it takes its name and which may have been used to ram and stun prey and also in intraspecific combat. Early restorations showing Tylosaurus with a dorsal crest were based on misidentified tracheal cartilage, but when the error was discovered, depicting mosasaurs with such crests was already a trend.[3][4]

Size

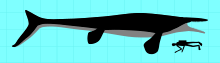

Along with plesiosaurs, sharks, fish, and other mosasaurs, Tylosaurus was a dominant predator of the Western Interior Seaway during the Late Cretaceous. The genus was among the largest of the mosasaurs (along with Mosasaurus hoffmannii), with the possibly conspecific[2] Hainosaurus bernardi reaching lengths up to 12.2 m (40 ft), and T. pembinensis reaching comparable sizes.[5] T. proriger, the largest species of Tylosaurus, reached lengths of about 14 m (46 ft).[6]

Discovery and naming

Like many other mosasaurs, the early history of this taxon is complex and involves the infamous rivalry between two early American paleontologists, Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh. Originally, the name "Macrosaurus" proriger was proposed by Cope for a fragmentary skull and thirteen vertebrae collected from near Monument Rocks in western Kansas in 1868.[7] It was placed in the collections of the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology. Only a year later, Cope redescribed the same material in greater detail and referred it, instead, to the English mosasaur taxon Liodon. Then, in 1872, Marsh named a more complete specimen as a new genus, Rhinosaurus ("nose lizard"), but soon discovered that this name had already been used for a different animal. Cope suggested that Rhinosaurus be replaced by yet another new name, Rhamposaurus which also proved to be preoccupied. Marsh finally erected Tylosaurus later in 1872, to include the original Harvard material as well as additional, more complete specimens which had also been collected from Kansas.[8] A giant specimen of T. proriger, recovered in 1911 by C. D. Bunker near Wallace, Kansas is one of the largest skeletons of Tylosaurus ever found. It is currently on display at the University of Kansas Museum of Natural history.

In 1918, Charles H. Sternberg found a Tylosaurus, with the remains of a plesiosaur in its stomach.[9] The specimen is currently mounted in the United States National Museum (Smithsonian) and the plesiosaur remains are stored in the collections. Although these important specimens were briefly reported by C. H. Sternberg (1922), the information was lost to science until 2001. This specimen was rediscovered and described by Everhart (2004a). It is the basis for the story line in the 2007 National Geographic IMAX movie Sea Monsters, and a book by the same name (Everhart, 2007).

A photograph of a Tylosaurus skull was taken by George F. Sternberg about 1926 after he collected and prepared the specimen. It was discovered in the Smoky Hill Chalk of Logan County, Kansas. Sternberg offered the specimen to the Smithsonian and included a photograph in his letter to Charles Gilmore. Copies of the original photos are in the archives of the Sternberg Museum of Natural History (FHSM). The specimen is FHSM VP-3, the exhibit specimen in the same museum.

A 34 feet (10 m) long Tylosaurus found in Kansas by Alan Komrosky in 2009 is now on display at the Museum of World Treasures in Wichita, Kansas.[10]

Classification

Though many species of Tylosaurus have been named over the years, only a few are now recognized by scientists as taxonomically valid. They are as follows: Tylosaurus proriger (Cope, 1869[7]), from the Santonian and lower to middle Campanian of North America (Kansas, Alabama, Nebraska, etc.) and Tylosaurus nepaeolicus (Cope, 1874 [11]), from the Santonian of North America (Kansas). Tylosaurus kansasensis, named by Everhart in 2005[12] from the late Coniacian of Kansas, has been shown to be based on juvenile specimens of T. nepaeolicus.[13] It is likely that T. proriger evolved as a paedomorphic variety of T. nepaeolicus, retaining juvenile features into adulthood and attaining much larger adult size.[13]

A closely related genus, Hainosaurus, is known from the Cretaceous of North America and Europe. Both Tylosaurus and Hainosaurus are members of the group Tylosaurinae [14] and are referred to informally as "tylosaurines" or "tylosaurs." Research published in 2016, however, indicates that Hainosaurus is likely congeneric with Tylosaurus.[2] Bell [15] placed the tylosaurines together with the plioplatecarpine mosasaurs (Platecarpus, Plioplatecarpus, etc.) in an informal monophyletic grouping which he called the "Russellosaurinae."

The cladogram below follows the cladogram from a 2011 analysis by paleontologists Takuya Konishi and Michael W. Caldwell.[16]

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

Stomach contents associated with specimens of Tylosaurus proriger indicate that this ferocious mosasaur had a varied diet, including fish, sharks, smaller mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, and flightless diving birds such as Hesperornis. In some paleoenvironments, Tylosaurus seems to have preferred shallow, nearshore waters (as with the Eutaw Formation and Mooreville Chalk Formation of Alabama), while favoring deeper water farther out from shore in other environments (as with the Niobrara Chalk of the western U.S.). Tylosaurus is believed to have hunted by stunning or disabling prey by ramming it, much as killer whales do: a fact supported by the fact that this genus of mosasaur had a specially reinforced skull built to withstand the stresses of such impacts according to Takuya Konishi et al.. Further research by Konishi on an infant specimen also indicates Tylosaurus was also capable of free-swimming as a newborn.[17]

The Talkeetna Mountains Hadrosaur was a hadrosaurid of indeterminate classification whose carcass appeared to have been deposited in a bathyal or outer shelf environment that later became Alaska's Matanuska Formation. Every element of its skeleton not found in a concretion bore many closely spaced ovualar conical depressions ranging in diameter from 2.12–5.81 mm (0.083–0.229 in) and 1.64–3.62 mm (0.065–0.143 in) deep. These depressions are probably bite marks. The depressions are not symmetrical enough for gastropod drill marks and are not shaped like sponge borings. None of the preserved fish fossils of the Matanuska Formation fit the size or geometry of the borings. The size and spacing and shape by contrast, however, closely resembles the teeth of Tylosaurus proriger. The apparent tooth marks are unlikely to have occurred before the carcass was washed out to sea since that would have punctured the body, preventing the buildup of bloating gases that allowed the carcass to drift out to sea in the first place. The distribution of bite marks corresponds inversely to the presence of flesh in the animal. For instance, lower limb bones sustained the most damage because there was the least amount of flesh shielding the bones at those locations. The concretions formed as the flesh chemically reacted to the seafloor on the largest parts of the animal where the scavenging mosasaur would be unable to fully wrap its jaws around the carcass. Bones pulled free from the carcass were buried in the mud and preserved in mudstone.[18]

References

- ↑ Paulina Jiménez-Huidobro; Michael W. Caldwell; Ilaria Paparella; Timon S. Bullard (2018). "A new species of tylosaurine mosasaur from the upper Campanian Bearpaw Formation of Saskatchewan, Canada". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. Online edition. doi:10.1080/14772019.2018.1471744.

- 1 2 3 Paulina Jimenez-huidobro and Michael W. Caldwell (2016). "Reassessment and reassignment of the early Maastrichtian mosasaur Hainosaurus bernardi Dollo, 1885, to Tylosaurus Marsh, 1872". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Online edition: e1096275. doi:10.1080/02724634.2016.1096275.

- ↑ "H.F. Osborn 1899". Oceansofkansas.com. April 18, 2008. Retrieved January 28, 2013.

- ↑ "Mosasaur Fringe". Oceansofkansas.com. January 13, 2013. Retrieved January 28, 2013.

- ↑ Lindgren, J. (2005). "The first record of Hainosaurus (Reptilia, Mosasauridae) from Sweden". Journal of Paleontology. 79 (6). doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2005)079[1157:TFROHR]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ "Fact File: Tylosaurus Proriger from National Geographic". Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- 1 2 Cope ED. 1869. [Remarks on Macrosaurus proriger.] Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 11(81): 123.

- ↑ Marsh OC. 1872. Note on Rhinosaurus. American Journal of Science 4 (20): 147.

- ↑ "Tylosaur food". Oceansofkansas.com. Retrieved January 28, 2013.

- ↑ "Museum Of World Treasures". Worldtreasures.org. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved January 28, 2013.

- ↑ Cope ED. 1874. Review of the vertebrata of the Cretaceous period found west of the Mississippi River. U. S. Geological Survey of the Territories, Bulletin 1 (2): 3-48.

- ↑ Everhart, M.J. (2005). "Tylosaurus kansasensis, a new species of tylosaurine (Squamata, Mosasauridae) from the Niobrara Chalk of western Kansas, USA" (PDF). Netherlands Journal of Geosciences. 84 (3): 231–240. doi:10.1017/S0016774600021016.

- 1 2 Paulina Jiménez-Huidobro, Tiago R. Simões & Michael W. Caldwell. (2016). Re-characterization of Tylosaurus nepaeolicus (Cope, 1874) and Tylosaurus kansasensis Everhart, 2005: Ontogeny or sympatry? Cretaceous Research, doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2016.04.008

- ↑ Williston SW. 1898. Mosasaurs. The University Geological Survey of Kansas, Part V. 4: 81-347 (pls. 10-72).

- ↑ Bell GL. Jr. 1997. A phylogenetic revision of North American and Adriatic Mosasauroidea. pp. 293-332 In: Callaway J. M. and E. L Nicholls, (eds.), Ancient Marine Reptiles, Academic Press, 501 pages.

- ↑ Konishi, Takuya; Michael W. Caldwell (2011). "Two new plioplatecarpine (Squamata, Mosasauridae) genera from the Upper Cretaceous of North America, and a global phylogenetic analysis of plioplatecarpines". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 31 (4): 754–783. doi:10.1080/02724634.2011.579023.

- ↑ https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/10/181012152610.htm

- ↑ Pasch, A. D.; May, K. C. (2001). "Taphonomy and paleoenvironment of a hadrosaur (Dinosauria) from the Matanuska Formation (Turonian) in South-Central Alaska". In Tanke, D.H.; Carpenter, K.; Skrepnick, M. W. Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Indiana University Press. pp. 219–236.

- Bell GL. Jr. 1997. Part IV: Mosasauridae - Introduction. pp. 281–292 In: Callaway J. M. and E. L Nicholls, (eds.), Ancient Marine Reptiles, Academic Press, 501 pages.

- Everhart MJ. 2001. Revisions to the biostratigraphy of the Mosasauridae (Squamata) in the Smoky Hill Chalk Member of the Niobrara Chalk (Late Cretaceous) of Kansas. Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science 104 (1-2): 56-75.

- Everhart MJ. 2005. Earliest record of the genus Tylosaurus (Squamata; Mosasauridae) from the Fort Hays Limestone (Lower Coniacian) of western Kansas. Transactions 108 (3/4): 149-155.

- Everhart MJ. 2005. Oceans of Kansas - A Natural History of the Western Interior Sea. Indiana University Press, 322 pp.

- Kiernan CR. 2002. Stratigraphic distribution and habitat segregation of mosasaurs in the Upper Cretaceous of western and central Alabama, with an historical review of Alabama mosasaur discoveries. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 22 (1): 91-103.

- Russell DA. 1967. Systematics and morphology of American mosasaurs (Reptilia, Sauria). Yale Univ. Bull. 23: 241 pp.

- Novas FE, Fernández M, Gasparini ZB, Lirio JM, Nuñez HJ, Puerta P. 2002. Lakumasaurus antarcticus, n. gen. et sp., a new mosasaur (Reptilia, Squamata) from the Upper Cretaceous of Antarctica. Ameghiniana 39 (2): 245-249.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tylosaurus. |