County of Loon

| County of Loon | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1040–1366 | |||||||||

Coat of arms

| |||||||||

|

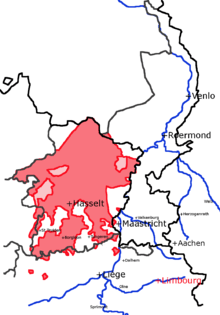

The Low Countries around 1250, Loon (Looz) in yellow | |||||||||

| Status | County | ||||||||

| Capital |

Borgloon Hasselt | ||||||||

| Common languages | Limburgish | ||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||||||

| Government | County | ||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||

• First mentioned | 1040 | ||||||||

• Gained Rieneck | 1106 | ||||||||

• Acquired Chiny | 1227 | ||||||||

• To Heinsberg | 1336 | ||||||||

• Annexed by Liège | 1366 | ||||||||

| 1795 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

The County of Loon (Dutch: Graafschap Loon, French: Comté de Looz) was a province of the ancien regime Holy Roman Empire, which by 1190 came under the overlordship of the Prince-bishop of Liège.[1] It lay north of Liège and west of the Maas river (French: Meuse) in present-day Flemish-speaking Belgium. Loon's first definite count was brother to a bishop of Liège, and over generations the county grew and then came under direct control of the bishops, as their largest Dutch-speaking secular lordship. Once it reached its maximum extent its territory corresponded closely to that of the current Belgian province of Limburg.

The Dutch-speaking "Good Cities" of Liège (French: bonnes villes, which were cities with certain rights) were Beringen, Bilzen, Borgloon, Bree, Hamont, Hasselt, Herk-de-Stad, Maaseik, Peer and Stokkem, all in Loon, and all in Belgian Limburg today.[2] Like other areas which eventually came under the power of the Prince Bishop of Liège, despite strong political links Loon was never formally part of the unified lordship of the "Low Countries" which united almost all of the Benelux in the Middle Ages, and continued to unite almost all of today's Belgium until the ancien regime was ended by the French revolution. The communities of Loon then became part of France, and later of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, in a province which united them with their eastern neighbours. In 1839 the territory of Loon was split off again definitively joining the new Kingdom of Belgium as Belgian Limburg.

Although the chief city came to be Hasselt, now also the provincial capital of Belgian Limburg, the original chief city of this county before it expanded was Borgloon, which was originally just called Loon (French: Looz), now in the southern part of modern Limburg. This southern and oldest part of the county is geographically in the hilly Belgian region along the Dutch-French language border known as Hesbaye or Haspengouw in Dutch, a region which had four counties in 870. From its earliest times as a county however, Loon also seems to have had lordships stretching to the Maas valley, and later it expanded northwards into the low-lying Dutch-speaking Kempen region (French: Campine) which had been part of the old Frankish gau and Roman pagus of Toxandria.

Origins

Like the neighboring county of Duras, records mentioning the county of Loon begin in the early 11th century, but very little is certain about its origin. The immediately preceding generations had seen many rebellions, confiscations, and expulsions. The whole region of Lower Lotharingia had been in an unsettled status, as the eastern and western kingdoms of the Carolingian dynasty contested for control of the previously independent area, together with the local magnates, especially the Regnarids. By 1000 the area was under lasting control of the eastern kingdom of Germany and not only Loon, but also other well-known counties such as Hainaut and Leuven, were developing into the forms known in the later Middle Ages, but these counties were put together from component parts with complex histories that are now difficult to reconstruct.

The Regnarids had controlled all or most of these areas. In particular, a count named Rodolphe, believed to be the brother of Reginar III, had a county which included areas similar to the ones thought to have been held by the first count of Loon, not only in Haspengouw, but also on the Maas.[3] But in 958 the brothers were exiled, and although the two sons of Reginar III returned successfully in 973, establishing the power bases that became the counties of Hainaut and Leuven, the fate of their uncle Rodolphe is unknown. The county of Loon however clearly happened in this context of a return of the Regnarids to the region. Another remarkable fact to explain is that the first count's brother was a powerful Bishop.

According to the most widely accepted hypothesis, developed by Leon Vanderkindere and up-dated by Jan Baerten and others, the counts of Loon were related to the Regnarids, but members of the "Balderics family", descendants of Count Ricfrid. This family had stronger links to the Ottonian dynasty in Germany than the Regnarids, and two members of this family named Balderic (or Balderich, Palderih, etc) had already held the powerful bishoprics in Utrecht and Liège at different times in the 10th century. Vanderkindere argued that Count Giselbert of Loon and his brother Bishop Balderic II must descend from the known marriage of a sister of the exiles Reginar III and Rodolphe with Count Nevelong, a son of Ricfrid, who is known to have had children named Rodolphe, Balderic I (Bishop of Liège), and Bertha (who married Arnulf son of Isaac, Count of Cambrai). This links Loon's origins to both the earlier Reginars who had apparently held Hocht and Avernas, and two earlier bishops named Balderic. Furthermore, Balderic II of Liège was recorded as being a relative to Arnulf the son of Bertha, as well as the Regnarid Lambert I, Count of Louvain.[4]

Vanderkindere specifically proposed that Giselbert the first definite count of Loon was the son of the younger Count Rodolphe, not the Regnarid, but his nephew the son of Nevelong. Both Vanderkindere and Baerten believed that this Rodolphe must have held a county in the Loon area, making him a likely father to the three brothers. Baerten's reasoning is based on a 967 charter made by Bertha, this Rodolphe's sister, making a grant of land near Brustem to the Abbey of St Truiden (in the Loon region). The first witness, Count Eremfrid, is the name of a local count who appears in other charters. (He was thought by Baerten to be brother, her uncle and a brother of Nevelong, but Jongbloed (2009, p. 25) describes this Ehrenfrid as still unidentified, and believes Bertha's uncle was already dead.) The 4th witness is a Count Rodulfus, with no description of where he was from.[5] There have been chronological concerns raised about this proposal, because this sighting of Rodolphe is so much earlier than any definite record of Count Giselbert and his brothers in the next century. Furthermore, the only old source to mention a parent for Count Giselbert calls him Otto.[6] Although this source is not considered reliable for this period, Hein Jongbloed has proposed that there was a son of Bertha and Arnulf named Otto who is a better proposal, although this does not work better chronologically.[7] Winter on the other hand, has proposed that there may have been an Otto who was son of Rodolphe, and father to the first count and his brothers.[8]

Whoever his parents were, the first certain Count (Dutch graaf, Latin comes, French comte) of Loon was the 11th century Giselbert (modern Dutch Gijsbert, equivalent of modern English and French "Gilbert"). Exactly what territory he held is still uncertain, and his brother Arnulf is also mentioned as a count in various records. Although arguably all of the charters which describe the brothers as siblings of bishop Balderic II of Liège are dubious, there is considered to be enough evidence to be accept this relationship.[9]

A charter dated 24 Jan 1040 mentions a "county of Haspinga in the pagus Haspengouw", which had been the possession of count Arnold, understood to be the brother of Giselbert, also known as Arnulf. With this much debated charter Emperor Henry III granted to the Cathedral of Saint-Lambert in Liège.[10] There is no other clear mention of this county within the pagus of the same name, so it raises the question of what this title implied both geographically and legally. Furthermore, there is no record ever of Arnulf as count of Loon, but Haspinga has been interpreted as being either the same as the county of Loon (Verhelst (1984, p. 248)) or as a lordship which held Loon under it (Baerten, and others), although it might simply have been one geographical part of Hesbaye, different to the one his brother held.

Connected to this open question, not only is the parentage of Giselbert, Arnulf and Balderic unknown, but also their connection to the next two count brothers, Emmo and Otto, is considered uncertain. They are thought to be the sons of either Giselbert or Arnulf. While Giselbert is the obvious proposal, Souvereyns & Bijsterveld (2008, p. 116) lean towards the position of Verhelst and favor Arnulf as their father. A major argument for the position of Verhelst is that Emmo named his son and heir Arnulf/Arnold, and the name Giselbert was never used by his descendants. (Otto named his son Giselbert, but this was also the name of his father-in-law.)

Another important charter in discussions about the origins of the County of Loon is the 1078 grant by Countess Ermengarde to the Bishop of Liège, of allodial land in key places in the Count of Loon. Her possessions can not be explained by her ancestry, or her known husband, and so it has long been suggested (for example by Vanderkindere, Baerten, Kupper) that she must have first married a Count of Loon, normally presumed to be Arnold, because he is normally presumed to have had no heirs.[11]

History

In 1040 Emperor Henry III treated the County of Haspinga as land held under the Prince-Bishopric of Liège, and this may have included Loon. But it appears that the count of Loon's various powers and possessions included some which were held under other overlords including the Emperor himself.

In the generation after the 3 brothers Balderic, Gilbert, and Arnulf, Emmo became the next count of Loon while his brother Otto became count of Duras, based in the western part of Haspengouw, through his wife Oda. The county of Duras was held as a fief of the Duchy of Brabant, and was inherited by Otto's son Giselbert, and in turn by his son Otto. It eventually became part of Loon, under Count Gerard around 1194.

Count Arnold (or Arnulf) I, the son of Emmo, is according to Baerten (1969 p.40) the first Count of Loon for whom we can discuss any political activity. In 1106 he was able to strengthen his position, when he acquired the possessions of the extinct Counts of Rieneck through his marriage. He also probably built the castle which was at Borgloon.[12] His son Arnold II, Count of Loon, founded the Abbey of Averbode.

The son and heir of Arnold II was Louis (Dutch Lodewijk) I. He founded Averbode Abbey by charter dated 1135, and was count of Loon, Stadtgraf of Mainz, and count of Rieneck, both in modern Germany. He increased Loon's territory adding Kolmont (now in Tongeren) together with Bilzen. He strengthened the fort there and gave the city freedoms. He also gave city freedom did the same in Brustem (now in St Truiden), which came under threat as a Loon enclave in the County of Duras.

Count Gerard (sometimes called Gerard "II", and sometimes Gerard I), the next count of Loon and Rieneck, fortified Brustem and Kolmont, and moved the seat of the count to Kuringen, which is today in Hasselt (the modern capital of the region). There he founded the Herkenrode Abbey, for women of the order of Cîteaux (Cistercians). In Loon, the enduring conflict with his Liège overlords culminated in an 1179 campaign by Prince-Bishop Rudolf of Zähringen, whose troops devastated the county's capital at Borgloon in 1179. In 1193 he also inherited the county of Duras from his relatives, but had to accept Brabant's suzerainty over that territory for the time being. This area gave power over church land in Sint-Truiden, Halen, and Herk de Stad, effectively defining what is today still the southwestern border of Belgian Limburg. His son Gerard III was heir, and he in turn passed Loon to Arnold IV, but Rieneck to another son, Louis.

Count Arnold IV by marriage acquired the French-speaking County of Chiny in 1227, and brought the main line of the counts of Loon to the high point of its territorial expansion. The comital male line became extinct with the death of Louis IV of Loon in 1336 and the Loon and Chiny estates were at first inherited by the noble House of Sponheim at Heinsberg with the consent of the Liège bishop. In 1362 Prince-Bishop Engelbert III of the Marck nevertheless seized Loon and finally incorporated it into the Liège territory in 1366.

The county remained a separate entity (quartier) within Liège, whose prince-bishops assumed the comital title. When the bishopric was annexed by Revolutionary France in 1795, the county of Loon was also disbanded and an adjusted version of the territory became part of the French département of Meuse-Inférieure, along with Dutch Limburg to the east of the Maas. After the defeat of Napoleon, the département became part of the new United Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1815, and received its modern name of Limburg as a way for the kingdom to preserve the old title of the medieval Duchy of Limburg, which was nearby. However, in 1830, Belgium was created, splitting the Kingdom, and the position of Limburg and Luxemburg became a cause of conflict between the two resulting Kingdoms. In 1839, under international arbitration, it was finally decided to split Limburg and Luxemburg into their two modern parts. The western part of Limburg, corresponds roughly to the old County of Loon, and became part of Belgium. Both parts kept their new name of Limburg.

Counts of Loon

- Count Otto? Named as count of Loon in a much later, and confused seeming, record of his son Baldric II's installation as Bishop of Liège in 1008. His existence is doubted, for example by Baerten.

- Giselbert (count at least 1015-1036), he and his brother Arnold were both referred to as counts in Haspengouw, and Giselbert was specifically referred to as count of Loon.

- Emmon (d.1078), clearly called "count of Loon" in own lifetime. His brother Otto became count of Duras, but the brothers were collectively called counts of Loon also. His father is likely to have been Giselbert, but it is not certain.

- Arnold I (count at least 1090-1125), son of Emmo, married Agnes, daughter and heiress of Count Gerard of Rieneck, Burgrave of Mainz. (His contemporary, another Giselbert, the son of his uncle Otto, was count in Duras.)

- Arnold II (count in 1135), son of Arnold I. Founded Averbode Abbey.

- Louis I (1139–1171), son of Arnold II, married Agnes, daughter of Count Folmar V of Metz

- Gerard (1171–1191), son, married Adelaide, daughter of Count Henry I of Guelders

- Louis II (1191–1218), son, married Ada, daughter of Count Dirk VII of Holland, also Count of Holland 1203 - 1207, followed by his brothers as guardians of his minor nephews Louis III and Arnold IV:

- Henry (1218), another son of Gerard, died soon after.

- Arnold III (1218–1221), another son of Gerard, also Count of Rieneck, married Adelaide, daughter of Duke Henry I of Brabant.

- Louis III (1221–1227), grandson of Gerard, son of Gerard, Count of Rieneck, also Count of Rieneck 1221 - 1243, renounced Loon in favour of his younger brother.

- Arnold IV (1227–1273), another grandson of Gerard and son of Count Gerard of Rieneck, married Joanna, daughter of Louis IV the Younger, Count of Chiny, also Count of Chiny (as Arnold II)

- John I (1273–1279), son, married Matilda, daughter of William IV, Count of Jülich, secondly Isabelle de Condé

- Arnold V (1279–1323), son, also Count of Chiny 1299 - 1313, married Margaret of Vianden

- Louis IV (1323–1336), son, also Count of Chiny (as Louis VI) since 1313, married Margaret, daughter of Duke Theobald II of Lorraine

Male line extinct, succeeded by:

- Theodoric, (1336–1361) son of Gottfried of Sponheim, Lord of Heinsberg and Mechtild of Loon, sister of Count Louis IV, also Count of Chiny and Lord of Heinsberg

- Gottfried (1361–1362), nephew, son of John of Heinsberg, married Philippa, daughter of Count William V of Jülich, also Count of Chiny and Lord of Heinsberg, sold the comital title to:

- Arnold VI of Rumigny (1362–1366), also Count of Chiny (as Arnold IV), claimant, renounced in favour of Liege,

Notes

- ↑ Count Gerard of Loon declared himself to hold Loon of the Bishop, in an Imperial Diet. See Vaes pp.32-3.

- ↑ See for example Vaes p.119. The Dutch speaking cities were specifically called the cités thioises, where "thioise" is a word related to English "Dutch".

- ↑ A document of 946 refers to "villa Lens in comitatu Avernas temporibus Rodulphi comitis" showing there was a count Rodolphe who held a county called Avernas. (Lens is probably not Loon but Lens-St-Servais (fr), or neighbouring Lens-St-Remy (fr), near Avernas in the modern french speaking commune of Geer. See for example Revue Belge de Numismatique 1948 for the suggestion Lens-St-Servais and Verhelst who gives St. Remy. In the same period, records also show a count Rodolphe held Aldeneyck (near Maaseik) in a county named Huste, believed to be centred at Hocht. The seats of these two early counties are in the southwest and northeast of the Loon area. Hocht is in modern Lanaken which like Maaseik is on the Maas river, so probably originally part of one of the 2 Maasgaus mentioned in the treaty of Meerssen in 870 (Baerten 1965, part 2). Avernas is in modern Hannut in French speaking Wallonia, and its territory must have overlapped the later county of Duras, held by the family of the Counts of Loon. It is generally thought that both records refer to one person.

- ↑ That bishop Balderic II of Liège had common ancestry with Count Arnoul, who modern historian believe to mean Arnoul of Valenciennes is mentioned in his biography the Vita Balderici Ep. Leodensis link. That bishop Balderic II had common ancestry with Lambert Count of Louvain is from the Gesta episcoporum Cameracensium, lib. III, ch. 5, M.G.H., SS., t. vii, p. 467-468.

- ↑ The charter is known from a later confirmation in the Cartulaire de l'abbaye de Saint-Trond (Piot edition, Volume 1, p.72.)

- ↑ Gestorum Abbatem Trudonensium Continuatio Tertia 1007, MGH SS X, p.382

- ↑ See Jongbloed (2008) "Flamenses" Bijdragen en Mededelingen Gelre p.50. The primary source mentioning Otto is the Gestorum Abbatem Trudonensium Continuatio Tertia 1007, MGH SS X, p. 382. Jongbloed proposed the existence of this Otto son of Bertha based on witness lists.

- ↑ J.M. Van Winter (1981) "De voornaamste adelijke geslachten in de Nederlanden in de 10de en 11de eeuw" in Blok, Algemene geschiedenis der Nederlanden, cited by Jongbloed.

- ↑ There are many mentions of the relationship, and medieval forgeries were often wholly or partly based on older real documents. Kupper (1981): "Les documents qui éclairent les origines du prélat — documents diplomatiques faux ou suspects, sources narratives très tardives — sont loin d’offrir toutes les garanties. Nous estimons cependant que leur témoignage se fait l’écho d’une tradition basée sur la réalité." Vaes, following Baerten, emphasizes that in 1031, Bishop Reginard, Balderic II's successor, describes a grant made in the previous generation where Gislebert was named as both brother to Balderic and count of Loon. Kupper says that this document is also a false copy, though probably based on an older real act. "Cet acte est un faux qui se base probablement sur un document de 1026-1028"

- ↑ MGH DD H III 35 p.45 (comitatum Arnoldi comitis nomine Haspinga in pago Haspingowi).

- ↑ Kupper (2013) discusses this grant in detail.

- ↑ Vaes p.129

References

- Baerten (1965), "Les origines des comtes de Looz et la formation territoriale du comté", Revue belge de philologie et d'histoire, 43 (2): 468

- Baerten (1965), "Les origines des comtes de Looz et la formation territoriale du comté (suite et fin)", Revue belge de philologie et d'histoire, 43 (4)

- Baerten, Jean (1969), Het Graafschap Loon (11de - 14de eeuw) (PDF)

- Jongbloed (2008), "Flamenses in de elfde eeuw", Bijdragen en Mededelingen Gelre

- Jongbloed, Hein H. (2006), "Immed "von Kleve" (um 950) : Das erste Klevische Grafenhaus (ca, 885 - ca. 1015) als Vorstufe des geldrischen Fürstentums" (PDF), Annalen des historischen Vereins für den Niederrhein

- Jongbloed, Hein H (2009), "Listige Immo en Herswind. Een politieke wildebras in het Maasdal (938-960) en zijn in Thorn rustende dochter", Jaarboek. Limburgs Geschied- en Oudheidkundig Genootschap, 145: 9–67

- Kupper, Jean-Louis (1981), Liège et l’Église impériale aux XIe-XIIe siècles, Presses universitaires de Liège, doi:10.4000/books.pulg.1472, ISBN 9782821828681

- Kupper, Jean-Louis (2013), "La donation de la comtesse Ermengarde à l'Église de Liège (1078)" (PDF), Bulletin de la Commission royale d'Histoire Année, 179: 5–50

- Souvereyns; Bijsterveld (2008), "Deel 1: De graven van Loon", Limburg - Het Oude Land van Loon

- Vanderkindere, Léon (1902), "9", La formation territoriale des principautés belges au Moyen Age (PDF), 2, p. 128

- Vaes, Jan (2016), De Graven van Loon. Loons, Luiks, Limburgs, ISBN 9789059087651

- Verhelst, Karel (1984), "Een nieuwe visie op de omvang en indeling van de pagus Hasbania (part 1)", Handelingen van de Koninklijke Zuidnederlandsche Maatschappij voor Taal- en Letterkunde en Geschiednis, 38

External Links

- Charles Cawley, Lower lotharingia, nobility on the MEDLANDS project hosted on the website of the Foundation for Medieval Genealogy. (Self-published)