Counts of Hesbaye

The Counts of (or in) Hesbaye were Counts named as having lordships in the important Frankish "country" (Latin: pagus, Dutch: gouw) called Hesbaye (French, also Hesbaie; Dutch Haspengouw; Latin Haspinga and Hasbania) in the early Middle Ages. Ewig (1969), for example, proposed that this area together with the neighbouring Maas valley, formed one of the old "duchies" in the Merovingian kingdom of Austrasia, possibly named Mansuaria, based on the core (Kernraum) of the large Roman civitas of Tongeren. Counts associated with the area had numerous relations with the major family dynasties of the medieval Franks.

In modern times Hesbaye and Haspengouw are geographical terms still (used for example in tourism, but also describing a specific agricultural landscape), and do not have any geo-political importance. Possibly, it was never a single county and always referred partly to a geographical understanding. The region is in eastern Belgium, but its boundaries have not necessarily been fixed over the centuries. It is now considered to be south of the river Demer, and west and north of the river Maas. In the dutch-speaking northern part, it is considered to only be east of the Gete, but it is thought that it once stretched as far west as Louvain on the Dyle river. The Catholic archdeaconry of Hesbaye not only stretched westwards but also surprisingly far eastwards over the Maas, as far as Aachen in modern Germany. In its origins however, it may once have been a name for a smaller area, for example the area near Overhespen and Neerhespen, both now in Linter, and it has also been proposed that a small County with the derived name of Haspinga existed between the three oldest towns, Maastricht, Tongeren and Liège, and the rivers Jeker and Maas.

The Hesbaye was an important region for the Merovingian and Carolingian Frankish aristocracy and clergy, straddling the northernmost stretch of the medieval Germanic-Romance language border in Europe, with Salian Franks permitted by the Roman emperor Julian the Apostate to settle north of the Hesbaye in Toxandria already in the 4th century, confronting the Romanized Christian population who had their Roman capital Tongeren, still in the Hesbaye today. Today, French and Wallonian dialect, both Romance languages, are still spoken in the southern part of the area, while Dutch and Limburgish dialect, which both derive from Frankish, are spoken in Tongeren and northwards.

Given the paucity of records from the Merovingian period when this territory is first mentioned, until the 11th and 12th centuries, when it became less politically important, it has been very difficult for modern historians to piece together how the counties and lordships were defined either geographically or legally. It seems clear at least that there could be several counts in the area at the same time, and also that there was (at least in 1040) one specific county which was itself called "Haspinga", but was distinct from the geographical Haspengouw which it was in. By that time, the region was being ruled by lordships such as the County of Loon, and County of Duras, as well as the growing neighbouring powers of the County of Louvain, County of Hainaut, and Prince-Bishopric of Liège, whose power reached further outside the region.

Name

In the earliest records, the Germanic element "gau" was not included as part of the name, and the typical Latin spelling is Hasbania. Occasionally the name is in a adjectival form indicating "(of the) Hasbanien(s)" (Hasbaniensis). Maurits Gysseling suggested the first part of the name, Has-, could technically have come from the word Chatti, an ancient German tribe whose name apparently changed into the later Hesse following known pronunciation changes which happened in Germany, but this is considered unlikely to be the real origin. The second element could be related to the word for the medieval concept of "ban", meaning a type of authority or lordship, and is similar to endings of other Frankish regions known from this period. Another common proposal is that the name was originally an older name of a locality within the region, such as the one where the villages of Overhespen and Neerhespen are.[1]

Verhelst (p.245 n.45) proposed that the small number cases of medieval Latin which include the Germanic "gau" ending are un-coincidentally in or near the old deaconry of Tongeren, which he proposed to be the historical core of the Hesbaye. Therefore, he proposed, the terms Hasbania and Hespengouw can not be assumed to have identical meanings in all records, even though in modern Dutch the form with "gouw" is now the only one, while in modern French the form without is the only one.

Earliest records (8th and 9th century)

The earliest record reported by Daris (p.36) is in 680 in a record by King Theuderic III granting lands to the Abbey of St Vaast in Arras. Places included there are near Sint Truiden (Halmaal, Halmala; Muizen, Musinium; and possibly Groseas), but Nonn dates this same document to 875-877.[2] Another mistaken early identification is in a falsified document attributed to the Merovingian king Dagobert. The earliest mention Nonn gives is in the medieval biography of Bavo of Ghent (622–659) which says that Bavo came from the "ducatus" of the Hasbaniensis, indicating that there was a dukedom.

Hesbaye, or at least the country of the Hesbainien people, is next mentioned in a charter of 741/2 which exists in several versions, wherein a Count or even Duke named Robert, son of Lambert, granted lands near Diest to Sint-Truiden Abbey.[3] The third continuation of the Gesta Abbatum Trudonensium (p.371) in its report of the charter describes the count as Robertus comes vel dux Hasbanie ("count or Duke of Hasbania"). This Robert, it says, is also the one mentioned as a Duke in the medieval biography (Vita) of Bishop Eucherius of Orléans. When Charles Martel exiled him to Cologne this was under the custody of the said Duke Robert of Hasbania (Hasbanio Chrodoberto duce).[4] A remarkable point about this early mention of Hesbaye is that this area (not near the river Maas) is described as "pago Hasbaniensi et Masuarinsi" the land of Hasbanians and Masuarians. There are only a small number of apparent references to the second term. Masuaria has been seen by for example Gorissen, Ewig, and Nonn, as representing an older name for the larger area (similar to the archdeaconry of Hesbaye) which included a part of Maas valley. (Gorissen relates it the Merovingian "Via Mansuerisca(fr)(de)(nl)" which was in the Ardennes, but which he understood to be a road named after its destination near Maastricht. Ewig and Nonn do not agree with the relevance of the road, but do believe that a 714 document concerning Susteren in the Maas valley north of Maastricht is relevant.)

(Based on his name, this Count or Duke Robert is speculated by Christian Settipani to be a direct ancestor of the Robertians and the House of Capet. And Robert may well have been related to Ermengarde, the wife of Louis I the Pious, because her great uncle Bishop Chrodegang was named in The Gesta Episcoporum Mettensis as being from Hasbania and of very noble Frankish descent ("ex pago Hasbaniensi" and "Francorum ex genere primæ nobilitatis progenitus"). Chrodegang's parents are known to have been named Sigramnus and Landrada, although their background can only be speculated upon.)

Around 800, the Bishop of Liège addressed himself to the faithful naming only Condroz, Lomme (later the core of County of Namur), Hasbania, and the Ardennes.[5] (The northern part of the Roman civitas probably no longer had clear boundaries, and missionary work to extend the Christian diocese was on-going at this time.[6])

Later, Count Ekkebard was one of the leaders of the pagus of Hesbaye in 834 who tried to negotiate the release of Emperor Louis.[7] (Possibly the same as the person as Count Etkard who was killed, and had two sons captured, at the siege of Toulouse against Pepin II, King of Aquitaine.[8]) So it seems that by Carolingian times, the region may have had several rulers.

In the period leading up to the Treaty of Meerssen, an important figure in this region was a count named Gilbert (or Giselbert etc), who appears to be the ancestor of the so-called Regnarids who dominate the region in the next century. Two territorial holdings are described in documents: he was count in Darnau, which later became a part of the County of Hainaut, and also (by Nithard) "comes Mansuariorum", "Count of the Mansuari", the rare term which historians associate with the "pago Hasbaniensi et Masuarinsi" of Count Robert near Diest in 741, and with both the Hesbaye and Maas valley to its east.[9]

Treaty of Meerssen and counties in Hesbaye

Discussion about the counts of Hesbaye has been guided by the description of the divisions of Lotharingian territories agreed to in the Treaty of Meersen of 8 August 870 between Louis the German, King of East Francia, and his half-brother Charles the Bald, King of the West Franks. The treaty allocated the 4 counties of Hasbania (in Hasbanio comitatus IV) to Charles, apparently all west of the Maas river, and not including the 2 Maas gaus, nor the gau of Liège, all 3 divided by the river. The reference to four unnamed counties within Hesbaye suggests that it might have been a geographical entity with no single count of Hesbaye, if indeed there ever was. No reference to these four counties, or any ruling counts, apart from in the county of Hesbaye itself, has been found prior to the 870 agreement.

| Some places mentioned in the Treaty of Meersen MGH SS (Annales et chronica aevi Carolini) 488-489 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| To Charles (Latin) | translation | To Ludwig/Louis | translation |

| Masau superior de ista parte Mosae | Upper Masau on this side of the Maas | Item Masau superior quod de ista parte est | Upper Masau on this side of the Maas |

| Masau subterior quantum de ista parte est | Lower Masau on this side of the Maas | Masau subterior quantum de ista parte | Lower Masau on this side of the Maas |

| Liugas quod de ista parte Mosae est & pertinet ad Vesatum | gau of Liège on this side of the Maas and its pertinances at Visé | Liugas quod est de ista parte | gau of Liège on this side of the Maas |

| in Hasbanio comitatus IV | in Hesbaye 4 counties | Berch, Castellum | on Maas near Roermond[10] |

| S Servatii | Abbey of St Servatius at Maastricht | Districtum Trectis | Districtum of Maastricht |

| Sancti Laurentii Leudensi | Monastery of St Lawrence Liège | Abbatiam de Aquis | Abbey at Aachen |

| Echa | Maaseik | Abbatium Suestre | Abbey of Susteren |

| Tungris | Tongeren | Districtum Aquense | Districtum of Aachen |

| Condrusto | Condroz | Abbatias prumiam et stabolau | Abbeys of Prüm and Stavelot |

Vanderkindere proposed four counties based on river boundaries, and names of counties mentioned in old records. The most important counter-arguments come from Baerten, and later Verhelst, who both referred especially to medieval church jurisdictions, (not only deaconries, but also old traditions about processions made to leading churches) arguing that these tended to follow political reality, but with a long lag, thus helping us see older political boundaries. Vanderkindere's proposals were as follows, with counter-proposals shown as alternatives.

- 1. "Northwest" (Louvain?). Between the Gete and Dyle rivers, in the eastern area of modern Flemish and Walloon Brabant, Vanderkindere proposed a large "northwestern" county of Louvain already existing in 870, including Diest. Today, much of this area is called "Hageland". Verhelst and Baerten agreed with such a western county, though not necessarily already named "Louvain", and smaller, with for example Diest and Zoutleeuw in a middle county ("Avernas", see below). Verhelst argued that because Louvain became politically powerful, its "Brabant" archdeaconry became larger and more politically independent of the rest of the Hesbaye.

- 2. "Northeast". In and around the southern half of modern Belgian Limburg Vanderkindere proposed one large "northeastern" Hesbaye county in 870, between Gete, Demer and Jeker, including the area of the both the later counties of Duras and Loon. Baerten and Verhelst disagreed that it was so big, allocating the western (Duras) section of Belgian Limburg to a central county of Avernas. (See below.)

- 3a. "Southeast" (Haspinga). Vanderkindere also considered the southeastern area between Liège and Maastricht and the Jeker and Maas rivers as one of the 4 counties of 870. He proposed this would also be the county of Haspinga as mentioned in 1040 (comitatum Arnoldi comitis nomine Haspinga in pago Haspingowi), granted by Emperor Henry III to the Cathedral of Saint-Lambert in Liège by charter dated 24 Jan 1040.[11] This county clearly used a Latin form derived from the name of the pagus which it is within. It was argued already by Jean de Hocsem in the middle ages that this had represented the name of an over-arching lordship, covering all of Hesbaye, with the Count of Loon under it. Vanderkindere saw this southeastern county as the county of these overlord counts, based on the proposal that a lordship of this area was later associated with the advocates of Hesbaye under the Bishopric. Baerten agreed, but Verhelst disagreed that this was one of the 870 counties and argued that the county of Hesbaye found in old records was larger, and could be equated to the whole medieval deaconry of Tongeren together originally with the French-speaking deaconry of Hozémont (fr) to its south, stretching all the way to the Maas. In effect, Verhelst saw Haspinga as originally united with the "northeast" county.[12] Other mentions of a county named after the pagus/gau are few. Daris and Nonn interpret a 956 charter involving Jemeppe-sur-Meuse this way, it being described as being in the pagus Hasbaniensis in the county of the same (in ipse pago Hasbaniense in comitatus ipsius). Nonn adds that Stier near Donceel was described as being in a county named Asbanio in 961.[13]

- 3b. Eastern (Maastricht hinterland). Verhelst did believe for different reasons that there was a small county on the Maas near Maastricht, near this same area. According to him the easternmost 870 county of Hesbaye was equivalent to the leftbank part of the easternmost deaconry of the Hesbaye, which included Maastricht and Visé. (In contrast, Baerten described the hinterland of Maastricht as part of the "district" of Maastricht, which is separately named in 870.)

- 4a. "Southwest" (Brunengeruz). Near Hoegaarden and Tienen, the meeting point of the modern provinces Vanderkindere proposed that the poorly known county of Brunengeruz could be considered the remnants of a 4th "southwestern" county of Hesbaye of 870. Also known as Brugeron in older sholarship, it was named in a charter under which Emperor Otto III confirmed properties of the church of Liège including comitatum de Brunengeruuz. Neither Baerten nor Verhelst list it as one of the 4 likely 870 counties. Verhelst argued explicitly that it was a newer creation which split out of the older western county in the 10th century. Baerten (1965a) argued that at least the part around Jodoigne had been part of the central county of Avernas. Nevertheless, both Baerten and Verhelst agreed there was a middle county between modern Louvain and Tongeren, but both believed it to be Avernas which existed already in 870.

- 4b. Central (Avernas). As mentioned above, while Baerten and Verhelst see Brunengeruz as a later creation, they would propose a county of Avernas between these western areas, and the "northeastern" part of Hesbaye. While Baerten (1965a) accepted Vanderkindere's idea that the southern parts near the Maas were part of Haspinga (above) Verhelst equated this to the four medieval deaconries of St Truiden, Zoutleeuw (later in Brabant, associated with Leuven), and French-speaking Andenne and Hanret (fr). Thus it would have stretched from Diest all the way to the Maas. The county's seat must have been at the villages of Avernas-le-Bauduin (fr) and Cras Avernas (fr), now both part of Hannut, in the east of modern Belgian Limburg. (Another difference between Baerten and Verhelst, as mentioned above, is that the "Brunengeruz" area around Hoegaarden the Great Gete was originally part of the western county according to Verhelst approach, whereas Baerten felt Jodoigne at least was part of Avernas.)

Because the evidence starts in the 10th century, Avernas will be discussed further below.

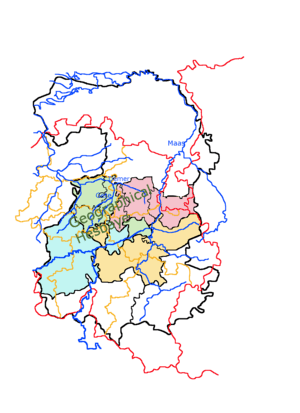

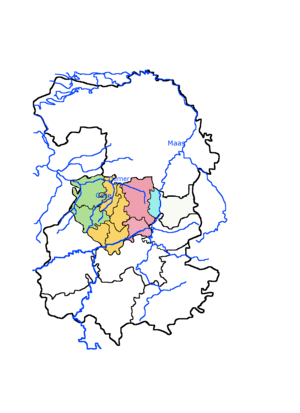

| The archdioceses and the possible 4 counties of Hesbaye in the Treaty of Meerssen (870): Proposals of Verhelst (1984) | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Later medieval Archdioceses under the Bishop of Liège, until 1559. Hesbaye is pink. Brabant is green. Hainaut is blue. Condroz is yellow. Hainaut and Brabant are clearly named after the counties to the west, but these grew in importance only from around 1000. In contrast, both Hesbaye and Condroz church archdioceses stretched surprisingly eastwards over the Maas, although other uses of those two terms did not normally cover that area. For orientation, modern political boundaries are shown in red (national) and orange (provincial). | Map showing the proposal by Karl Verhelst for the 4 counties of Hesbaye (Haspengauw) mentioned in the 870 Treaty of Meerssen. According to such proposals Hesbaye (Haspengouw) archdiocese was reduced in size after 870, at least in the west. The proposed 870 Avernas, and St Truiden archdiocese, is shown in yellow, which then lost territory to the rising powers of Louvain and Hainaut. The most northeastern part is the later rump of this archdiocese, which became the basis of the County of Duras in the 11th century. |

Counties of Avernas and "Huste"

As mentioned above, Baerten and Verhelst believe that there must have been at least two counties in the area where Vanderkindere proposed one northeastern county in 870. Apart from the church jurisdictions, the counties of Avernas and Huste (or Hocht) are known from only three 10th century records, one mentioning both. They are seen to be earlier versions of the 11th century counties of Duras and Loon:

- Approximately 946, a charter mentions "villa lens in comitatu avernae temporibus rodulphi comitis" (Villa Lens in the County of Avernas under the rule of Count Rodulphe).[14] Lens is the name of two neighboring villages near the villages of Avernas, Lens-St-Servais (fr), and Lens-St-Remy (fr).

- 4 Jul 952. Alden-Eyck near Maaseik (not in the Hesbaye, but later connected to it by the counts of Loon) is described as being "in pago Huste in comitatu Ruodulphi" (in the country of Huste, in the county of Rudolf).[15] Huste or Hufte is generally considered to be a word derived from Hocht, in Lanaken, also on the Maas but approximately 30km southwards. Van de Weerd has proposed it was Hoeselt. Wherever it was, it must have been seat of a territory.[16]

- The only other mention of both Huste and Avernas, from the same approximate period, is geographically distant from Huste, but close to Borgloon, the future seat of the county of Loon. A charter dated between 927 and 964 and probably around 950, mentioned the places, Muizen (nl) and Buvingen (nl) (both in Gingelom), and Heusden being in Avernas; and Heers and Engelmanshoven as being in a county called "Hufte", or Huste.[17] The two groups of places are noted by Baerten, Verhelst and others as being close, but separated by the old medieval deaconry boundaries of St Truiden and Tongeren, and in the 11th century probably also the boundaries between the counties of Duras and Loon ran in a similar way.

Huste or Hufte is considered by Baerten, Gorissen and others be a word derived from Hocht (nl), in Lanaken, also on the Maas but approximately 30km southwards, close to Maastricht and the Hesbaye. Van de Weerd has proposed that Huste was Hoeselt, close to Hocht, but in the Hesbaye. Wherever it was, Huste has been proposed to be the seat of an original core territory of the county of Loon in the 11th century. However doubts remain. In Aldeneik it was a "pagus" in the county of Rudolf. Near Borgloon it was the name of the county, but the count was not named.

10th century Regnarids

By the start of the 10th century the House of Reginar, the family of Reginar I "Longneck" (d.915), were becoming the dominant magnates of the whole Lower Lotharingian region. There are indications they had direct interests in the county of Hesbaye. He was Lay Abbot of important Abbeys stretching from the Maas to the Mosselle through the Ardennes, Saint-Servais in Maastricht, Echternach, Stavelot-Malmedy, and Saint-Maximin in Triers (approximately the border defined in 870). However his secular titles and activities are mainly only known from much later sources which are considered to be of uncertain reliability. Dudo of Saint-Quentin, in describing the great deeds of the early Normans, calls Reginar I (who, along with a prince of the Frisians named Radbod, was an opponent of Rollo) a Duke of both Hainaut and Hesbaye.[18] Centuries later William of Jumièges, and then later still, Alberic de Trois Fontaines followed Dudo using the same titles when describing the same events. He was variously referred to as Duke, Count, Marquis, missus dominicus, but historians doubt that these titles were connected to a particular territory. That he called himself a Duke is known from a charter at Stavelot 21 July 905.[19]

Reginar I had two known sons. The eldest Gilbert became Duke of Lotharingia, but died a rebel at the Battle of Andernach. Reginar II (adult 915-932) who was apparently a count in some family possessions. Reginar II also had two known sons, Reginar III and Rudolf. Rudolf is associated with Hesbaye, but Reginar III was exiled in 958, and Rudolf seems to have at least had possessions confiscated. As mentioned above, in the period before 958 a Count Rudolf is mentioned in one of the two mentions of the county of Avernas and one of the two mentions of Huste; and a third document mentioned both, without naming any counts, but it showed that Avernas and Huste had a boundary between St Truiden and Borgloon.

Then later, 17 Jan 966, a charter states that a Count Rudolf’s property at Gelmen (between St Truiden and Borgloon) had been confiscated and was now in the county Werner in the pagus of Hesbaye.[20]

A charter dated 24 Jan 966, mentions grants to Nivelles by a Count Reginar, and a son of his called Liechard (or Liethard), who gave Gingelom, in Hesbaye. A Count Rudolf also appears in that charter, but he is not described as a relative and Lentlo, which he granted, is Lillois (fr) south of Brussels, and not (as Vanderkindere thought) the same as Lens near Avernas.[21]

The sons of Reginar III, Reginar IV and his brother Lambert, returned in 973 and killed Werner (or Garnier) and his brother Renaud, but what happened to Rudolf and any claims he had in Hesbaye is not clear from records. Werner also seems to have been present in this area. The widely accepted suggestion of Vanderkindere is that a branch of the Balderics family related to the Reginars, and the Ottonians, were able to maintain a presence in the area even under Werner, both on the Maas and in Hesbaye, eventually forming the County of Loon. Two counts in the area who are considered likely to be Balderics were Emmo or Eremfried, and a Rudolph, thought to be a younger count, different from the count or counts recorded as having previously lost Lens and Gelmen. Both names, Eremfridus and Rodulfus, appear as witnesses in a grant by Bertha, the mother of a Count Arnulf, of land in Brustem to St Truiden.[22]

However, apart from this 967 charter, and the 966 one concerning Nivelles, the Count who seems to have mainly replaced Werner was Emmo/Eremfried, whose family connections are unclear. Hein Jongbloed wrote 2 articles concerning Eremfrieds in the Balderic family (2006) and (2009), but he gives no strong proposal about the identity of this Eremfried in Hesbaye and Maasland. He does however (2009 p.25) add another possible sighting of the same person, and it mentions a late Count Rudolf who apparently can be associated with Avernas. In a charter made in Capua, 26 July 982, "on the day that we fight the Saracens" Otto II certified that if a certain "Cunradus, son of the late count Rudolf" died, he wanted his possessions in Lotharingia to go to Gorze Abbey, and these included "curtis Velm in pago Haspongowe et in comitate Eremfridi comitis".[23] In the Battle of Cotrone itself (13 July 982, so it had already happened) it seems that both this Conrad, and this count Eremfried, lost their lives. Velm, now part of St Truiden, did come under Gorze Abbey, and a Count Irimfrid was recorded as dying.[24] However, this Conrad's possessions were widespread, and on the basis of those Vanderkindere (1902 pp.340-1) believes his father was Rodolphe Count of Ivois.[25] Of this Count however, Vanderkindere (p.342) says that given his connection to Velm it is "not without some likelihood" that he is a member of the Regnarid family, where the name Rodolphe was familiar.

11th century

In the 11th century, the counties become better known and those which survived can be the subjects of more specialized discussion.

Eastern counties

In the 11th century the "northwestern" Counties of Duras and Loon started appearing in records, and records show such counts were considered to have counties in the pagus of Hesbaye. These two counties for the original core of today's Belgian Limburg. Loon had its seat in Borgloon, near Tongeren, and the town of Duras (nl) is today part of St Truiden. The first mention of Duras comes in two grants made by a widow of a count of Duras, named Herlendis. Several sons were named, but it seems the inheritance went to a grand-daughter Oda, who married a member of the comital family of Loon. Record of the comital family of Loon begins at a similar time, with Bishop Balderic II of Liège, the brother of two counts in Hesbaye, Gilbert, the first count to be specifically called "of Loon", and Arnulf.

Also mentioned in the 11th century, indeed only ever mentioned clearly on very few occasions, was Count Arnold's county of Haspinga, within the pagus of Haspengouw, also discussed above in relation to interpretations of the Treaty of Meerssen. When, in 1040, Emperor Henry III granted it to the Prince-Bishropic of Liege it is generally accepted that Count Arnold is the same as Arnulf the brother of Balderic and Gilbert, even though the actual definition of this county and what the grant encompassed is not clear. Baerten and others propose that Arnoldus had been holding a county which, apart from his own part of Hesbaye, also held his brother's county of Loon, meaning that this 1040 grant made the County of Loon already a lordship under the bishop. Prior records of a county named Haspinga are few.

Some decades later in 1078, another difficult-to-interpret grant to the bishop was made by a widow named Ermengarde. It included properties at not only the important Loon towns of Borgloon and Kuringen, but also closer to St Truiden, and even to the north, outside the Hesbaye. It has been suggested that in order to explain this she must have been married to Count Arnulf, but had no children with him.[26]

In Vanderkindere's "southeast", to the south of Duras and Loon, closer to the Maas in Wallonia, the county of Moha, was formed on the southern side of the Mehaigne river. Straddling the Maas to its south was the County of Huy, which had been created already before the 11th century, and already become the first county to be held directly by the Bishop of Liège.

Western counties

Very little is known of counties which appear to have been seated in Diest, Aarschot and "Brunengeruz" (near Hoegaarden), because as the 11th century began, the county of Louvain was becoming a dominant force in this region, and to its south, the counties of Namur and Hainaut had similar trajectories. Louvain and Hainaut were founded by the Reginars in the 10th century. Namur was apparently formed by a local family, putting together several smaller counties (Darnau, Lommegau etc).

Notes

- ↑ Nonn p.133

- ↑ Nonn p.134 n.698

- ↑ Despy (1961) gives a critical review of this document and its versions.

- ↑ Vita Eucherii episcopi Aurelianensis MGM Script. rer. mer. VII, 1920 pp.50-51

- ↑ Mansi, Sacrorum conciliorum nova et amplissima collectio, 13, column 1084

- ↑ J. Dhondt (1952) 'Proloog van de Brabantse geschiedenis. Een inleiding tot de politieke geschiedenis van Noord-Brabant in de 9de en 10de eeuw', in Bijdragen tot de studie van het Brabants Heem, III, p.14.

- ↑ Vita Hludowici Imperatoris 50, MGH SS II, p. 637

- ↑ Annales Bertiniani II 844, p.31.

- ↑ HGH SS rer. Germ. [44]: Nithardi Historiarum p.32

- ↑ It has been argued that Castellum is not Kessel near Roermond, but Chevremont, near Liège. See Schrijnemakers (1979) "Localisatie-problemen rond de plaatsnaam Kessel (bij Roermond)" Naamkunde .

- ↑ See MGH DD H III 35 p.45

- ↑ Verhelst argued that even Haspinga in 1040 would still have stretched north into the still-developing county of Loon, based around Borgloon, concluding that count Arnold in 1040 was effectively the count of Loon, and that Giselbert the previous count was already dead.

- ↑ Gesta Abbatum Gemblacensium MGH SS folio VIII p.529

- ↑ Beyer, Urkundenbuch zur Geschichte Vol 1, p.246 nr. 184.

- ↑ MGH DD Otto I p.235

- ↑ This Count Rudolf also apparently had more territory in another pagus. In a charter of 7 Oct 950, Kessel on the left bank of the Maas between Roermond and Venlo is described as being "in pago Masalant in comitatu Ruodolfi" (in the country of Maasland, in the county of Rudolf). (MGH DD Otto I p.210)

- ↑ Baerten dates this charter to 953-958. The charter is transcribed in the Cartulaire de l'abbaye de Saint-Trond Piot edition, Volume 1, pp.6-7

- ↑ Dudo: "Raginerum Longi-Colli, Hasbacensem et Hainaucensem ducem" Dudo, ii, 9.

- ↑ Parisot (1898) p.563

- ↑ MGH DD Otto I p.430

- ↑ MGH DD Otto I p.432

- ↑ The charter is known from a later confirmation in the Cartulaire de l'abbaye de Saint-Trond Piot edition, Volume 1, p.72.

- ↑ MGH DD OII p.326

- ↑ MGH SS folio XIII 205 Annales necrologici Fuldenses

- ↑ Also see how Conrad is remembered in Gorze itself: .

- ↑ Kupper (2013)

Sources

- Baerten, J (1962), "Le comté de Haspinga et l'avouerie de Hesbaye (IXe-XIIe siècles)", Revue Belge de Philologie et d'Histoire, 40 (4): 1149–1167

- Baerten, Jean (1965a), "In Hasbanio comitatus quatuor (Verdrag van Meersen, 870)", Koninklijke Zuinederlandse Maatschappij Voor Taal- en Letterkunde en Geschiedenis, XIX

- Baerten (1965), "Les origines des comtes de Looz et la formation territoriale du comté (suite et fin)", Revue Belge de Philologie et d'Histoire, 43 (4)

- Baerten, Jean (1969), Het Graafschap Loon (11de - 14de eeuw) (PDF)

- Daris, Jos. (1880), "L'ancienne principauté de Liége", Bulletin de l'Institut Archéologique Liégeois

- Despy, G (1961), "La charte de 741-742 du comte Robert de Hesbaye pour l'abbaye de Saint-Trond" (PDF), Annales du XXXVIIe Congrès de la Fédération Archéologique et Historique de Belgique, Bruxelles, 24-30 Août 1958: 82–91

- Ernst (1857), "Mémoire historique et critique sur les comtes de Hainaut de la première race", Bulletin de la Commission Royale d'Histoire, 9: 393–513

- Ewig, Eugen, Die Stellung Ribuariens in der Verfassungsgeschichte des Merowingerreichs, 1, pp. 450–471

- Jongbloed (2008), "Flamenses in de elfde eeuw", Bijdragen en Mededelingen Gelre

- Jongbloed, Hein H. (2006) "Immed "von Kleve" (um 950) : Das erste Klevische Grafenhaus (ca, 885 - ca. 1015) als Vorstufe des geldrischen Fürstentums", Annalen des historischen Vereins für den Niederrhein link

- Jongbloed, Hein H.. (2009) "Listige Immo en Herswind. Een politieke wildebras in het Maasdal (938-960) en zijn in Thorn rustende dochter", Jaarboek. Limburgs Geschied- en Oudheidkundig Genootschap vol. 145 (2009) p. 9-67

- Kupper, Jean-Louis (2013), "La donation de la comtesse Ermengarde à l'Église de Liège (1078)" (PDF), Bulletin de la Commission Royale d'Histoire Année, 179: 5–50

- Gorissen, P (1964), "Maasgouw, Haspengouw, Mansuarië", Revue Belge de Philologie et d'Histoire Année (42–2): 383–398

- Nonn, Ulrich (1983), Pagus und Comitatus in Niederlothringen: Untersuchung zur politischen Raumgliederung im frühen Mittelalter

- Parisot, Robert (1898), Le Royaume de Lorraine sous les Carolingiens also on google books.

- Verhelst, Karel (1984), "Een nieuwe visie op de omvang en indeling van de pagus Hasbania (part 1)", Handelingen van de Koninklijke Zuidnederlandsche Maatschappij Voor Taal- en Letterkunde en Geschiednis, 38

- Verhelst, Karel (1985), "Een nieuwe visie op de omvang en indeling van de pagus Hasbania (part 2)", Handelingen van de Koninklijke Zuidnederlandsche Maatschappij Voor Taal- en Letterkunde en Geschiednis, 39

- Vanderkindere, Léon (1902), "Chapter 9", La formation territoriale des principautés belges au Moyen Age (PDF), 2, p. 128

Primary sources

External links

- Medieval Lands Project, Die ROTBERTINER (self-published)

- Medieval Lands Project, FAMILY of ENGUERRAND COMTE de PARIS (self-published)

- Medieval Lands Project, COMTES de HESBAIE (self-published)

- Henry III project, Regnier I