Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe

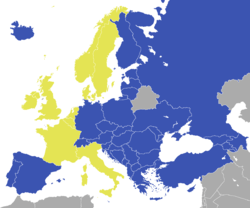

The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) is the parliamentary arm of the Council of Europe, a 47-nation international organisation dedicated to upholding human rights, democracy and the rule of law. The Council of Europe is an older and wider circle of nations than the 28-member European Union – it includes, for example, Russia and Turkey among its member states – and oversees the European Court of Human Rights.

The Assembly is made up of 324 members drawn from the national parliaments of the Council of Europe's member states, and generally meets four times a year for week-long plenary sessions in Strasbourg. It is one of the two statutory bodies of the Council of Europe, along with the Committee of Ministers, the executive body representing governments, with which it holds an ongoing dialogue. However, it is the Assembly which is usually regarded as the "motor" of the organisation, holding governments to account on human rights issues, pressing states to maintain democratic standards, proposing fresh ideas and generating the momentum for reform.

The Assembly held its first session in Strasbourg on 10 August 1949, making it one of the oldest international assemblies in Europe. Among its main achievements are:

- ending the death penalty in Europe by requiring new members to stop all executions

- making possible, and shaping, the European Convention on Human Rights

- high-profile reports exposing violations of human rights in Council of Europe member states

- assisting former Soviet countries to embrace democracy after 1989

- inspiring and helping to shape many progressive new national laws

- helping member states to overcome conflict or reach consensus on divisive political or social issues

Powers

Unlike the European Parliament (an institution of the European Union), the Assembly does not have the power to create binding laws. However, it speaks on behalf of 820 million Europeans and has the power to:

- demand action from the 47 Council of Europe governments, who – acting through the organisation's executive body – must jointly reply

- probe human rights violations in any of the member states

- question Prime Ministers and Heads of State on any subject

- send parliamentarians to observe elections and mediate over crises

- set the terms on which states may join the Council of Europe, through its power of veto

- inspire, propose and help to shape new national laws

- request legal evaluations of the laws and constitutions of member states

- sanction a member state by recommending its exclusion or suspension

Important statutory functions of PACE are the election of the judges of the European Court of Human Rights, the Council of Europe's Commissioner for Human Rights and its Secretary General, as well as the members of the Committee for the Prevention of Torture.

In general the Assembly meets four times per year in Strasbourg at the Palace of Europe for week-long plenary sessions. The nine permanent committees of the Assembly meet all year long to prepare reports and draft resolutions in their respective fields of expertise.

The Assembly sets its own agenda, but its debates and reports are primarily focused on defending human rights, promoting democracy, protecting minorities and upholding the rule of law.

Election of judges to the European Court of Human Rights

Judges of the European Court of Human Rights are elected by PACE from a list of three candidates nominated by each member state which has ratified the European Convention on Human Rights. A 20-member committee made up of parliamentarians with legal experience – meeting in camera – interviews all candidates for judge on the Court and assesses their CVs before making recommendations to the full Assembly, which elects one judge from each shortlist in a secret vote.[1] Judges are elected for a period of nine years and may not be re-elected.

Although the European Convention does not, in itself, require member states to present a multi-sex shortlist of potential appointees, in a 2004 resolution PACE decided that it "will not consider lists of candidates where the list does not include at least one candidate of each sex" unless there are exceptional circumstances .[2] As a result, around one third of the current bench of 47 judges are women, making the Court a leader among international courts on gender balance.

Achievements

The European Convention on Human Rights

At its very first meeting, in the summer of 1949, the Parliamentary Assembly adopted the essential blueprint of what became the European Convention on Human Rights, selecting which rights should be protected and defining the outline of the judicial mechanism to enforce them. Its detailed proposal, with some changes, was eventually adopted by the Council of Europe's ministerial body, and entered into force in 1953. Today, more than sixty years later, the European Court of Human Rights - given shape and form during the Assembly's historic post-war debates - is regarded as a global standard-bearer for justice, protecting the rights of citizens in 47 European nations and beyond, and paving the way for the gradual convergence of human rights laws and practice across the continent. The Assembly continues to elect the judges of the Court.

Exposing torture in CIA secret prisons in Europe: the "Marty reports"

In two reports for the Assembly in 2006 and 2007, Swiss Senator and former Prosecutor Dick Marty revealed convincing evidence that terror suspects were being transported to, held and tortured in CIA-run “secret prisons” on European soil. The evidence in his first report in 2006 - gathered with the help of investigative journalists and plane-spotters among others - suggested that a number of Council of Europe member states had permitted CIA "rendition flights" across their airspace, enabling the secret transfer of terror suspects without any legal rights. In a second report in 2007, Marty showed how two member states - Poland and Romania - had colluded in allowing "secret prisons" to be established on their territory, where torture took place. His main conclusions - subsequently confirmed in a series of rulings by the European Court of Human Rights, as well as a comprehensive US Senate report - threw the first real light on a dark chapter in US and European history in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, kicked off a series of national probes, and helped to make torture on European soil less likely.

Historic speeches made to PACE

In 2018 an online archive of all speeches made to the Parliamentary Assembly by heads of state or government since its creation in 1949 appeared on the Assembly's website, the fruit of a two-year project entitled "Voices of Europe". At the time of its launch, the archive comprised 263 speeches delivered over a 70-year period by some 216 Presidents, Prime Ministers, monarchs and religious leaders from 45 countries - though it continues to expand, as new speeches are added every few months.

Some very early speeches by individuals considered to be "founding fathers" of the European institutions, even if they were not heads of state or government at the time, are also included (such as Sir Winston Churchill or Robert Schuman). Addresses by eight monarchs appear in the list (such as King Juan Carlos I of Spain, King Albert II of Belgium and Grand Duke Henri of Luxembourg) as well as the speeches given by religious figures (such as Pope John Paul II) and several leaders from countries in the Middle East and North Africa (such as Shimon Peres, Yasser Arafat, Hosni Mubarak, Léopold Sédar Senghor or King Hussein of Jordan).

The full text of the speeches is given in both English and French, regardless of the original language used. The archive is searchable by country, by name, and chronologically.

Languages

The official languages of the Council of Europe are English and French, but the Assembly also uses German, Italian and Russian as working languages.[3] Each parliamentarian has separate earphones and a desk on which they are able to select the language which they would like to listen to. When foreign guests wish to address the Assembly in languages other than its working languages, they must bring their own interpreters.

Controversies

Sanctions against the Russian delegation

In April 2014, after the Russian parliament's backing for the occupation of Crimea and Russian military intervention in Ukraine, the Assembly decided to suspend the Russian delegation's voting rights as well as the right of Russian members to be represented in the Assembly's leading bodies and to participate in election observation missions. However, the Russian delegation remained members of the Assembly. The sanction applied throughout the remainder of the 2014 session and was renewed for a full year in January 2015, lapsing in January 2016.

In response, the Russian parliamentary delegation suspended its co-operation with PACE in June 2014, and in January 2016 - despite the lapsing of the sanctions - the Russian parliament decided not to submit its delegation's credentials for ratification, effectively leaving its seats empty. It did so again in January 2017 and again in January 2018. Russia's seats remain empty,

The sanctions applied only to Russian parliamentarians in PACE, the Council of Europe's parliamentary body. Russia continues to be a full member of the Council of Europe, and retains full rights in the organisation's other bodies, including its statutory executive body, the Committee of Ministers.[4]

Alleged corruption

In 2013, the New York Times reported that “some council members, notably Central Asian states and Russia, have tried to influence the organisation’s parliamentary assembly with lavish gifts and trips”.[5] According to the report, said member states also hire lobbyists to fend off criticism of their human rights records.[6] German news magazine Der Spiegel had earlier revealed details about the strategies of Azerbaijan’s government to influence the voting behaviour of selected members of the Parliamentary Assembly.[7]

In January 2017, following a series of critical reports by the European Stability Initiative (ESI) NGO, and concern expressed by many members of the Assembly, the Assembly's Bureau decided on a three-step response to these allegations, including the setting up of an independent, external investigation body. In May 2017, three distinguished former judges were named to conduct the investigation: Sir Nicolas Bratza, a British former President of the European Court of Human Rights; Jean-Louis Bruguière, a French former anti-terrorist judge and investigator; and Elisabet Fura, a former Swedish parliamentary Ombudsman and judge on the Strasbourg Court.[8] There are no other known examples in recent history of an international organisation setting up an independent, external anti-corruption probe into itself.

The investigation body, which was invited to carry out its task "in the utmost confidence", appealed for anyone with information relevant to its mandate to come forward, and held a series of hearings with witnesses. The investigation body's final report was published on 22 April 2018 after nine months of work, finding "strong suspicions of corruptive conduct involving members of the Assembly" and naming a number of members and former members as having breached the Assembly's Code of Conduct.

The Assembly responded by declaring, in a resolution, "zero tolerance for corruption". Following a series of hearings, it sanctioned many of the members or former members mentioned in the Investigative Body's report, either by depriving them of certain rights, or by excluding them from the Assembly's premises for life. It also undertook a major overhaul of its integrity framework and Code of Conduct.

Cultural divisions

Although the Council of Europe is a human rights watchdog and a guardian against discrimination, it is widely regarded as becoming increasingly divided on moral issues because its membership includes mainly Muslim Turkey as well as East European countries, among them Russia, where social conservatism is strong.[9] In 2007, this became evident when the Parliamentary Assembly voted on a report compiled by Liberal Democrat Anne Brasseur on the rise of Christian creationism, bolstered by right-wing and populist parties in Eastern Europe.[9]

Members

The Assembly has a total of 648 members in total – 324 principal members and 324 substitutes[10] – who are appointed or elected by the parliaments of each member state. Delegations must reflect the balance in the national parliament, so contain members of both ruling parties and oppositions. The population of each country determines its number of representatives and number of votes. This is in contrast to the Committee of Ministers, the Council of Europe's executive body, where each country has one vote. While not full members, the parliaments of Kyrgyzstan, Jordan, Morocco and Palestine hold "Partner for Democracy" status with the Assembly - which allows their delegations to take part in the Assembly's work, but without the right to vote - and there are also observer delegates from the Canadian, Israeli and Mexican parliaments.

Some notable former members of PACE include:

- former heads of state or government such as Britain's wartime leader Sir Winston Churchill, former German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, former Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, former Turkish President Abdullah Gül, former Cypriot President Glafcos Clerides, former Finnish President Tarja Halonen, former Georgian President Mikhail Saakashvili, former Albanian President Sali Berisha, and many others.[11]

- Dick Marty (Switzerland), appointed in late 2005 as rapporteur to investigate the CIA extraordinary renditions scandal and organ theft in Kosovo by the Kosovo Liberation Army from the Kosovo war, in 1998–2001[12]

- Marcello Dell'Utri (Italy), convicted for complicity in conspiracy with the Mafia (Italian: concorso in associazione mafiosa), a crime for which he was found guilty on appeal and sentenced to 7 years in 2010.[13]

- the Scottish soldier, adventurer, writer and MP Sir Fitzroy Maclean (United Kingdom), author of the autobiographical memoir and trevelogue Eastern Approaches, who was a member of PACE on two separate occasions, in 1972-3 and 1951-2.

Composition by parliamentary delegation

| Parliament | Seats | Accession date |

|---|---|---|

| 4 | 1995 | |

| 2 | 1994 | |

| 4 | 2001 | |

| 6 | 1956 | |

| 6 | 2001 | |

| 7 | 1949 | |

| 5 | 2002 | |

| 6 | 1992 | |

| 5 | 1996 | |

| 3 | 1961–1964, 1984 | |

| 7 | 1991 | |

| 5 | 1949 | |

| 3 | 1993 | |

| 5 | 1989 | |

| 18 | 1949 | |

| 5 | 1999 | |

| 18 | 1951 | |

| 7 | 1949 | |

| 7 | 1990 | |

| 3 | 1959 | |

| 4 | 1949 | |

| 18 | 1949 | |

| 3 | 1995 | |

| 2 | 1978 | |

| 4 | 1993 | |

| 3 | 1949 | |

| 3 | 1995 | |

| 3 | 1965 | |

| 5 | 1995 | |

| 2 | 2004 | |

| 3 | 2007[14] | |

| 7 | 1949 | |

| 5 | 1949 | |

| 12 | 1991 | |

| 7 | 1976 | |

| 10 | 1993 | |

| 18[15] | 1996 | |

| 2 | 1988 | |

| 7 | 2003 | |

| 5 | 1993[16] | |

| 3 | 1993 | |

| 12 | 1977 | |

| 6 | 1949 | |

| 6 | 1963 | |

| 18 | 1949 | |

| 12 | 1995 | |

| 18 | 1949 |

The special guest status of the National Assembly of Belarus was suspended on 13 January 1997.

Parliaments with Partner for Democracy status

Parliaments with Partner for Democracy status pledge to work towards certain basic values of the Council of Europe, and agree to occasional assessments of their progress. In return, they are able to send delegations to take part in the work of the Assembly and its committees, but without the right to vote.

| Parliament | Seats | Date |

|---|---|---|

| 6 | 2011 | |

| 3 | 2011[17] | |

| 3 | 2014[18] | |

| 3 | 2016[19] |

Parliaments with observer status

| Parliament | Seats | Date |

|---|---|---|

| 6 | 1996[20] | |

| 3 | ? | |

| 6 | 1999 | |

Parliamentarians with observer status

| Parliamentarians | Seats | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Turkish Cypriot Community | 2 | 2004[21][22][23][24] |

Composition by political group

The Assembly has six political groups.[25]

| Group | Chairman | Members |

|---|---|---|

| European People's Party (EPP/CD) | Stella Kyriakides | 168 |

| Socialists, Democrats and Greens Group (SOC) | Frank Schwabe | 162 |

| European Conservatives Group (EC) | Ian Liddell-Grainger | 83 |

| Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE) | Rik Daems | 76 |

| Unified European Left Group (UEL) | Tiny Kox | 34 |

| Free Democrats Group | Adele Gambaro | 22 |

| Members not belonging to any group | 59 |

Presidents

The Presidents of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe have been:

| Period | Name | Country | Political affiliation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1949 | Édouard Herriot (interim) | Radical Party | |

| 1949–51 | Paul-Henri Spaak | Socialist Party | |

| 1952–54 | François de Menthon | Popular Republican Movement | |

| 1954–56 | Guy Mollet | Socialist Party | |

| 1956–59 | Fernand Dehousse | Socialist Party | |

| 1959 | John Edwards | Labour Party | |

| 1960–63 | Per Federspiel | Venstre | |

| 1963–66 | Pierre Pflimlin | Popular Republican Movement | |

| 1966–69 | Geoffrey de Freitas | Labour Party | |

| 1969–72 | Olivier Reverdin | Liberal Party | |

| 1972–75 | Giuseppe Vedovato | Christian Democracy | |

| 1975–78 | Karl Czernetz | Social Democratic Party | |

| 1978–81 | Hans de Koster | People's Party for Freedom and Democracy | |

| 1981–82 | José María de Areilza | Union of the Democratic Centre | |

| 1983–86 | Karl Ahrens | Social Democratic Party | |

| 1986–89 | Louis Jung | Group of the European People's Party | |

| 1989–92 | Anders Björck | European Democratic Group | |

| 1992 | Geoffrey Finsberg | European Democratic Group | |

| 1992–95 | Miguel Ángel Martínez Martínez | Socialist Group | |

| 1996–99 | Leni Fischer | Group of the European People's Party | |

| 1999–2002 | Russell Johnston | Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe | |

| 2002–2004 | Peter Schieder | Socialist Group | |

| 2005–2008 | René van der Linden | Group of the European People's Party | |

| 2008–2010 | Lluís Maria de Puig | Socialist Group | |

| 2010–2012 | Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu | European Democratic Group | |

| 2012–2014 | Jean-Claude Mignon | Group of the European People's Party | |

| 2014–2016 | Anne Brasseur | Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe | |

| 2016–2017 | Pedro Agramunt | Group of the European People's Party | |

| 2017–2018 | Stella Kyriakides | Group of the European People's Party | |

| 2018 | Michele Nicoletti | Socialists, Democrats and Greens Group | |

| 2018- | Liliane Maury Pasquier | Socialists, Democrats and Greens Group | |

The Assembly elected Wojciech Sawicki (Poland)[26] as its Secretary General in 2010 for a five-year term of office which began in February 2011. In 2015 he was re-elected for a second five-year term, which began in February 2016.

See also

References

- ↑ PACE creates a special committee for the election of judges to the European Court of Human Rights, 24/06/2014.

- ↑ Adelaide Remiche (August 12, 2012), Election of the new Belgian Judge to the ECtHR: An all-male short list demonstrates questionable commitment to gender equality Oxford Human Rights Hub, University of Oxford.

- ↑ "Turkey's presence at Council of Europe increased". DailySabah. 24 May 2015.

- ↑ "Russia suspended from Council of Europe body". EuropeanVoice. 10 April 2014.

- ↑ Judy Dempsey (February 4, 2013), Corruption Undermining Democracy in Europe New York Times.

- ↑ Judy Dempsey (April 27, 2012), Where a Glitzy Pop Contest Takes Priority Over Rights International Herald Tribune.

- ↑ Ralf Neukirch (January 4, 2012), A Dictator's Dream: Azerbaijan Seeks to Burnish Image Ahead of Eurovision Der Spiegel.

- ↑ "Allegations of corruption within PACE: appointment of the members of the external investigation body". PACE: News. Council of Europe. May 30, 2017. Retrieved September 6, 2017.

- 1 2 Stephen Castle (October 4, 2007), European lawmakers condemn efforts to teach creationism International Herald Tribune.

- ↑ This number is fixed by article 26.

- ↑ "Members since 1949".

- ↑ "Council of Europe". coe.int. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- ↑ "Rai News: le ultime notizie in tempo reale – news, attualità e aggiornamenti". www.rainews24.rai.it.

- ↑ Previously part of Serbia and Montenegro: member since 2003.

- ↑ "PACE: News". assembly.coe.int.

- ↑ Previously part of Czechoslovakia, member since 1991.

- ↑ http://assembly.coe.int/nw/xml/XRef/X2H-Xref-ViewPDF.asp?FileID=18022&lang=en

- ↑ "PACE: News". coe.int. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- ↑ "PACE grants Jordan's Parliament Partner for Democracy Status". coe.int. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- ↑ "Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly". coe.int. Archived from the original on 28 February 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- ↑ "Turkish Cypriot Chamber of Commerce". ktto.net. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- ↑ "Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly". coe.int. Archived from the original on 21 February 2015. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- ↑ "Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly". coe.int. Archived from the original on 7 March 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- ↑ James Ker-Lindsay The Foreign Policy of Counter Secession: Preventing the Recognition of Contested States, p.149: "...despite strong opposition from the Cypriot government, The Turkish Cypriot community was awarded observer status in the PACE"

- ↑ "Political groups".

- ↑ "Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly". coe.int. Archived from the original on 17 April 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

Further reading

- (in French) Le Conseil de l'Europe, Jean-Louis Burban, publisher PUF, collection « Que sais-je ? », n° 885.