Controversy over ethnic and linguistic identity in Montenegro

The controversy over ethnic and linguistic identity in Montenegro is an ongoing dispute over the national identity, ethnic and linguistic identity of Montenegrins. The central issue is whether Montenegrins constitute a distinct ethnic group or a subgroup of Serbs (along with Serbs from Serbia, Bosnian Serbs, etc.). This divide has its historical roots in the first two decades of the 20th Century, during which the pivotal political issue has been the dilemma between retaining national sovereignty of Montenegro, advocated by supporters of the Petrović-Njegoš dynasty, most notably Greens, i.e. members of the True People's Party, and supporters of integration with the Kingdom of Serbia, and consequently with other South Slavic peoples under the Karađorđević dynasty, advocated by the Whites (gathered around the People's Party). This dispute has been renewed during the dissolution of Yugoslavia and consequent separation of Montenegro which declared its independence from the state union with Serbia in 2006. According to the 2011 census data, 44.98% identify as ethnic Montenegrins, while 28.73% declare as ethnic Serbs; 42.88% speak Serbian and 36.97% declare Montenegrin as their native language.

Nationalism in Montenegro

There are two variants of nationalism in Montenegro, anti-Serbian and pro-Serbian.[1]

Historical background

Early modern period

Metropolitan Danilo I (1696-1735) called himself "Duke of the Serb land".[2] Metropolitan Sava called his people, the Montenegrins, the "Serbian nation" (1766).[3] Petar I was the conceiver of a plan to form a new Slavo-Serbian Empire by joining Bay of Kotor, Dubrovnik, Dalmatia, Herzegovina to Montenegro and some of the highland neighbours (1807),[4] he also wrote "The Russian Czar would be recognized as the Tsar of the Serbs and the Metropolitan of Montenegro would be his assistant. The leading role in the restoration of the Serbian Empire belongs to Montenegro."

History

In the late 19th century Montenegro's aspirations mirrored that of Serbia — unification and independence of Serb-inhabited lands.[5] Njegoš (1813–1851), regarded the greatest Montenegrin poet, was a leading Serb figure and instrumental in codifying the Kosovo Myth as the central theme of the Serbian national movement.[5] The Petrović-Njegoš dynasty tried to take the role as the Serb leader and unifier, but Montenegro's small size and weak economy led to the recognition of the primacy of the Karađorđević dynasty (in Serbia) in this respect.[5] Although Montenegrins espoused a Serb identity, they were also proud of their state, especially in the Cetinje area, the capital of the Kingdom of Montenegro.[5] The sense of distinct statehood bred an autonomist sentiment in part of the Montenegrin population following the unification with Serbia (and dissolution of Montenegro) in 1918.[5]

It has been argued that there was no separate Montenegrin nation before 1945. The language, history, religion and culture were considered unquestionably Serbian.[6] Josef Korbel stated, in 1951, that "The Montenegrins proudly called themselves Serbs, and even today it would be difficult to find people of the older generations who would say they are Montenegrin. Only young Communists accept and propagate the theory of a Montenegrin nation."[7] AVNOJ recognized five contituent peoples of Yugoslavia: Serbs, Croats, Slovenes, Macedonians and Montenegrins.[8]

Until the 1990s, most of the Montenegrins defined themselves as both Serbs and Montenegrins.[9] The vast majority of Montenegrins declared themselves as Montenegrins in the 1971–1991 censuses because they were citizens of the Socialist Republic of Montenegro.[9] The 1992 Montenegrin independence referendum saw 96% in favour of Montenegro remaining a part of rump Yugoslavia (FR Yugoslavia – Serbia and Montenegro).[10] Until 1996, a 'pro-Serbian consensus predominated in Montenegrin politics'.[11]

As Montenegro began to seek independence from Serbia with the Đukanović—Milošević split after the Yugoslav Wars, the Montenegrin nationalist movement emphasized the difference between the Montenegrin and Serbian identities and that the term "Montenegrin" no longer implied belonging to the wider Serb identity.[9] The people had to make a choice whether they supported Montenegrin independence – the choosing of identity seems to have been based on their stance on independence.[9] Now, those who supported independence redefined the Montenegrin identity as a separate identity (unlike the previous overlapping Montenegrin/Serbian identity), while those who supported federation with Serbia increasingly insisted on their Serb identity.[9]

The pro-Yugoslav (unionist) side, headed by Momir Bulatović, stressed that Serbians and Montenegrins shared the same ethnicity (as Serbs) and evoked 'the unbreakable unity of Serbia and Montenegro, of one people and one flesh and blood'.[12] Bulatović promoted an exclusive Serb identity for the majority Orthodox population.[12]

Revisionism

There is an ongoing historical revisionism in Montenegro, where a separate Montenegrin identity is promoted with the "Duklja (Doclean) narrative" as founding myth.[13]

Demographic history

| 1909 | 317,856 | ~95% | Principality of Montenegro | According to language. | |||

| 1921 | 199,227 | 181,989 | 91.3% | Andrijevica, Bar, Kolasin, Niksic, Podgorica and Cetinje counties of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia |

According to language: Serbo-Croatian | ||

| 1948 | 377,189 | 6,707 | 1.78 | 342,009 | 90.67 | People's Republic of Montenegro (part of FPR Yugoslavia) | First census in Yugoslavia |

| 1953 | 419,873 | 13,864 | 3.3 | 363,686 | 86.61 | People's Republic of Montenegro (part of FPR Yugoslavia) | |

| 1961 | 471,894 | 14,087 | 2.99 | 383,988 | 81.37 | People's Republic of Montenegro (part of FPR Yugoslavia) | |

| 1971 | 529,604 | 39,512 | 7.46 | 355,632 | 67.15 | Socialist Republic of Montenegro (part of SFR Yugoslavia) | |

| 1981 | 584,310 | 19,407 | 3.32 | 400,488 | 68.54 | Socialist Republic of Montenegro (part of SFR Yugoslavia) | |

| 1991 | 615,035 | 54,453 | 9.34 | 380,467 | 61.86 | Socialist Republic of Montenegro (part of SFR Yugoslavia) | Last census in Yugoslavia |

| 2003 | 620,145 | 198,414 | 31.99 | 267,669 | 43.16 | Montenegro as part of Serbia and Montenegro | First census after breakup of Yugoslavia. |

| 2011 | 620,029 | 178,110 | 28.73 | 278,865 | 44.98 | Independent Montenegro | First census as independent state. |

Language statistics in 2011

Gallery

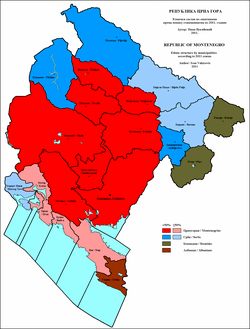

Ethnic structure by municipalities.

Ethnic structure by municipalities.- Linguistic structure by settlements.

Linguistic structure by municipalities.

Linguistic structure by municipalities.- Serbian language by settlements.

- Montenegrin language by settlements.

See also

|

| Part of a series on |

| Montenegro |

|---|

| History |

| Geography |

| Politics |

| Economy |

| Society |

References

- ↑ Sabrina P. Ramet (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-building and Legitimation, 1918-2005. Indiana University Press. pp. 316–. ISBN 0-253-34656-8.

- ↑ Džomić 2006.

- ↑ Vukcevich, Bosko S. (1990). Diverse forces in Yugoslavia: 1941-1945. p. 379. ISBN 9781556660535.

Sava Petrovich [...] Serbian nation (nacion)

- ↑ Banač 1988, p. 274

- 1 2 3 4 5 Trbovich 2008, p. 68.

- ↑ Lazarević 2014, p. 428.

- ↑ Josef Korbel (1951). Tito's Communism. Book on Demand. pp. 53–. ISBN 978-5-88379-552-6.

- ↑ Trbovich 2008, p. 142.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Huszka 2013, p. 113.

- ↑ Bideleux & Jeffries 2007, p. 477.

- ↑ Huszka 2013, pp. 111–112.

- 1 2 Huszka 2013, p. 114.

- ↑ Lazarević 2014.

Sources

- Bideleux, Robert; Jeffries, Ian (2007). "Montenegro: To be or not to be?". The Balkans: A Post-Communist History. Routledge. pp. 471–511. ISBN 978-1-134-58328-7.

- Džomić, Velibor V. (2006). Pravoslavlje u Crnoj Gori [Orthodoxy in Montenegro]. Svetigora.

- Huszka, Beata (2013). "The Montenegrin independence movement". Secessionist Movements and Ethnic Conflict: Debate-Framing and Rhetoric in Independence Campaigns. Routledge. pp. 104–132. ISBN 978-1-134-68784-8.

- Lazarević, Dragana (2014). "The Montenegrin Case – Finding a Foundation Myth". Istorija i geografija: susreti i prožimanja [History and geography: meetings and permeations]. Belgrade. pp. 428–443. ISBN 978-86-7005-125-6.

- Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (1999). A history of the Balkans, 1804-1945. Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-04585-9.

- Trbovich, Ana S. (2008). A Legal Geography of Yugoslavia's Disintegration. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533343-5.

Further reading

- Džankić, Jelena (2014). "Reconstructing the Meaning of Being "Montenegrin"". Slavic Review. 73 (2): 347–371. doi:10.5612/slavicreview.73.2.347.

- Jovanović, Batrić (1989a). Peta kolona antisrpske koalicije : odgovori autorima Etnogenezofobije i drugih pamfleta.

- Jovanović, Batrić (1989b). Crnogorci o sebi: (od vladike Danila do 1941). Sloboda.

- Jovanović, Batrić (2003). Rasrbljivanje Crnogoraca: Staljinov i Titov zločin. Srpska školska knj.

- Malešević, Siniša; Uzelac, Gordana (2007). "A Nation‐state without the nation? The trajectories of nation‐formation in Montenegro". Nations and Nationalism. 13 (4): 695–716. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8129.2007.00318.x.

- Negrišorac, Ivan (2011). "Истрага предака: Социопатогени чиниоци у процесу формирања црногорске нације". Летопис Матице српске. Novi Sad: Matica srpska.

- Stamatović, Aleksandar (2007). Антисрпство у уџбеницима историје у Црној Гори. Podgorica: Српско народно вијеће. ISBN 978-9940-9009-1-5. (in Serbian)

- Troch, Pieter (2008). "The divergence of elite national thought in Montenegro during the interwar period". Tokovi istorije (1–2): 21–37. ISSN 0354-6497.

- Vukčević, Nikola (1981). Етничко поријекло Црногораца [Ethnic origin of the Montenegrins]. Belgrade.

External links

- "Jedan jezik, a dve gramatike". Novosti.