Coefficient of relationship

The coefficient of relationship is a measure of the degree of consanguinity (or biological relationship) between two individuals. The term coefficient of relationship was defined by Sewall Wright in 1922, and was derived from his definition of the coefficient of inbreeding of 1921. The measure is most commonly used in genetics and genealogy. A coefficient of inbreeding can be calculated for an individual, and is typically one-half the coefficient of relationship between the parents.

In general, the higher the level of inbreeding the closer the coefficient of relationship between the parents approaches a value of 1, expressed as a percentage,[1] and approaches a value of 0 for individuals with arbitrarily remote common ancestors.

Coefficient of relationship

The coefficient of relationship ("r") between two individuals B and C is obtained by a summation of coefficients calculated for every line by which they are connected to their common ancestors. Each such line connects the two individuals via a common ancestor, passing through no individual which is not a common ancestor more than once. A path coefficient between an ancestor A and an offspring O separated by n generations is given as:

- pAO= 2−n⋅((1+fA)/(1+fO))½

where fA and fO are the coefficients of inbreeding for A and O, respectively.

The coefficient of relationship rBC is now obtained by summing over all path coefficients:

- rBC = Σ pAB⋅pAC.

By assuming that the pedigree can be traced back to a sufficiently remote population of perfectly random-bred stock (fA=0) the definition of r may be simplified to

- rBC = Σp 2−L(p),

where p enumerates all paths connecting B and C with unique common ancestors (i.e. all paths terminate at a common ancestor and may not pass through a common ancestor to a common ancestor's ancestor), and L(p) is the length of the path p.

To give an (artificial) example: Assuming that two individuals share the same 32 ancestors of n=5 generations ago, but do not have any common ancestors at four or fewer generations ago, their coefficient of relationship would be

- r = 2n⋅2−2n = 2−n which is, because n = 5,

- r = 25•2−10 = 2−5 = 1/32 which is approximately 0.0313 or 3%.

Individuals for which the same situation applies for their 1024 ancestors of ten generations ago would have a coefficient of r = 2−10 = 0.1%. If follows that the value of r can be given to an accuracy of a few percent if the family tree of both individuals is known for a depth of five generations, and to an accuracy of a tenth of a percent if the known depth is at least ten generations. The contribution to r from common ancestors of 20 generations ago (corresponding to roughly 500 years in human genealogy, or the contribution from common descent from a medieval population) falls below one part-per-million.

Human relationships

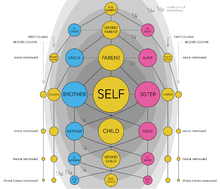

The coefficient of relationship is sometimes used to express degrees of kinship in numeric terms in human genealogy.

In human relationships, the value of the coefficient of relationship is usually calculated based on the knowledge of a full family tree extending to a comparatively small number of generations, perhaps of the order of three or four. As explained above, the value for the coefficient of relationship so calculated is thus a lower bound, with an actual value that may be up to a few percent higher. The value is accurate to within 1% if the full family tree of both individuals is known to a depth of seven generations.[2]

| Degree of relationship | Relationship | Coefficient of relationship (r) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | identical twins; clones | 100%[3] (1) |

| 1 | parent–offspring[4] | 50% (2−1) |

| 2 | full siblings | 50% (2−2+2−2) |

| 2 | 3/4 siblings or sibling–cousins | 37.5% (2−2+2−3) |

| 2 | grandparent–grandchild | 25% (2−2) |

| 2 | half siblings | 25% (2−2) |

| 3 | aunt/uncle–nephew/niece | 25% (2⋅2−3) |

| 4 | double first cousins | 25% (4⋅2−4) |

| 3 | great grandparent–great grandchild | 12.5% (2−3) |

| 4 | first cousins | 12.5% (2⋅2−4) |

| 6 | quadruple second cousins | 12.5% (8⋅2−6) |

| 6 | triple second cousins | 9.38% (6⋅2−6) |

| 4 | half-first cousins | 6.25% (2−4) |

| 5 | first cousins once removed | 6.25% (2⋅2−5) |

| 6 | double second cousins | 6.25% (4⋅2−6) |

| 6 | second cousins | 3.13% (2⋅2−6) |

| 8 | third cousins | 0.78% (2⋅2−8) |

| 10 | fourth cousins | 0.20% (2⋅2−10)[5] |

Most incest laws concern the relationships where r = 25% or higher, although many ignore the rare case of double first cousins. Some jurisdictions also prohibit sexual relations or marriage between cousins of various degree, or individuals related only through adoption or affinity. Whether there is any likelihood of conception is generally considered irrelevant.

See also

References

- ↑ strictly speaking, r=1 for clones and identical twins, but since the definition of r is usually intended to estimate the suitability of two individuals for breeding, they are typically taken to be of opposite sex.

- ↑ A full family tree of seven generations (128 paths to ancestors of the 7th degree) is unreasonable even for members of high nobility. For example, the family tree of Queen Elizabeth II is fully known for a depth of six generations, but becomes difficult to trace in the seventh generation.

- ↑ By replacement in the definition of the notion of "generation" by meiosis". Since identical twins are not separated by meiosis, there are no "generations" between them, hence n=0 and r=1. See genetic-genealogy.co.uk.

- ↑ "Kin Selection". Benjamin/Cummings. Retrieved 2007-11-25.

- ↑ This degree of relationship is usually indistinguishable from the relationship to a random individual within the same population (tribe, country, ethnic group).

Bibliography

- Wright, Sewall (1921). "Systems of Mating" (PDF). Genetics. 6: 111–178.

five papers:

- I) The biometric relations between offspring and parent

- II) The effects of inbreeding on the genetic composition of a population

- III) Assortative mating based on somatic resemblance

- IV) The effects of selection

- V) General considerations

- Wright, Sewall (1922). "Coefficients of inbreeding and relationship". American Naturalist. 56: 330–338. doi:10.1086/279872.

- Malécot, G. (1948) Les mathématiques de l’hérédité, Masson et Cie, Paris.

- Lange, K. (1997) Mathematical and statistical methods for genetic analysis, Springer-Verlag, New-York.

- Oliehoek, Pieter; Jack J. Windig; Johan A. M. van Arendonk; Piter Bijma (May 2006). "Estimating Relatedness Between Individuals in General Populations With a Focus on Their Use in Conservation Programs". Genetics. 173: 483–496. doi:10.1534/genetics.105.049940. PMC 1461426. PMID 16510792.