Claíomh Solais

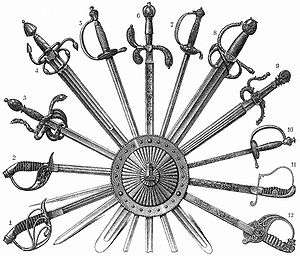

Claíomh Solais (reformed spelling), Claidheamh Soluis (pre-reform and Scottish Gaelic)[1] (Irish pronunciation: [klˠiːvˠ ˈsˠɔl̪ˠəʃ]; an cloidheamh solais (variant spelling[2]), rendered "Sword of Light", or "Shining Sword", or "a white glaive of light",[3] is a trope object that appears in a number of Irish and Scottish Gaelic folktales.[4]

The sword has been regarded as a legacy to the god-slaying weapons of Irish mythology by certain scholars, such as T. F. O'Rahilly: the analogue in the Irish Mythological Cycle being Lugh's sling that felled Balor, and their counterparts in heroic cycles are many, including the popular hero Cúchulainn's supernatural spear Gae bulga and his shining sword Cruaidín Catutchenn.[5][6]

A group of Sword of Light tales bear close resemblance in plot structure and detail to the Arthurian tale of Arthur and Gorlagon.[7][8]

Overview

The folk tales featuring the claidheamh soluis typically compels the hero to perform (three) sets of tasks, aided by helpers, who may be a servant woman, "helpful animal companions", or some other supernatural being. The majority of are also bridal quests (or involve the winning of husbands in e.g., Maol a Chliobain[9]).

The sword's keeper is usually a giant (gruagach, fermór) or hag (cailleach),[10] who oftentimes cannot be defeated except by some secret means. Thus the hero or helper may resort to the sword of light as the only effective weapon against this enemy.[11] But often the sword is not enough, and the supernatural enemy has to be attacked on a single vulnerable spot on his body. The weak spot, moreover, may be an external soul concealed somewhere in the world at large (inside animals, etc.), and in the case of "The Young King of Esaidh Ruadh",[12] this soul is encased within a nested series of animals.

The crucial secret to the hero's success is typically revealed by a woman, i.e., his would-be bride or the damsel in distress (the woman servant held captive by giants), etc. And even when the secret's revealant is an animal, she may in fact be a human transformed into beast (e.g. the great grey cat in "The Widow and her Daughters"[13]).

The secret about women is a theme borne in the title "The Shining Sword and the Knowledge of the Cause of the One Story about Women",[14] considered an essential part of the original Irish story (I) according to G. L. Kittredge's stemma of texts,[lower-alpha 1] even though "the woman" part is lacking (i.e. lost) in some variants, such as Kennedy's Fios Fath an aon Sceil ("perfect narrative of the unique story")[15][lower-alpha 2][lower-alpha 3] The "news of the death of Anshgayliacht", which occurs as a quest in another version[17] is also a corruption of this.[18] This reconstruction was made by G. L. Kittredge, who examines a groups of Sword of Light folktales cognate to Arthur and Gorlagon which he edited.[19] A more familiar Arthurian tale which embeds the quest of "What is it that women most desire?" is The Wedding of Sir Gawain and Dame Ragnelle.[20]

Analysis

Kittredge analyzes his group of Irish folktales (I)[21] to consist of layers of elements: namely a frame story which binds the quest for the "cause of the one story about women" with The Werewolf's Tale type; to this is attached The Quest for the Sword of Light and a large interpolation he calls the Defence of the Child type tale.[22]

The Defence of the Child tale portion is in itself a composite according to Kittredge, composed of a Faithful Dog tale and what he calls a The Hand and the Child type tale. The latter tale has the motif of a grasping hand that seizes the victim, and gets cut off in some cases, akin to Grendel's arm in Beowulf. The Irish and Gaelic tales of this type exhibit the tale or motif of Skilful Companions, which was studied by Theodor Benfey and is known to be widespread all over the world.[23]

Irish folktales

See under #Primary sources for bibliography of the compilations. Kittredge's sigla are given in boldface:

- "The Story of the Sculloge's son from Muskerry (Sceal Vhic Scoloige)" (Kennedy 1866, pp. 255-) K

- "Fios Fath an aon Sceil" (perfect narrative of the unique story) (Kennedy 1866, pp. 266-)

- "Eachtra air an sgolóig agus air an ngruagach ruadh (Adventure of the Sgolog and the Red Gruagach)" (Ó Briain 1889, Gaelic Journal 4, pp. 7–9; 26–28; 35–37[lower-alpha 4] J

- "The Weaver's Son and the Giant of the White Hill", (Curtin 1890, pp. 64–77). Here the "sword of sharpness".[25]

- "The Thirteenth Son of the King of Erin", (Curtin 1890, pp. 157–174)

- "Morraha; Brian More, son of the high-king of Erin, from the Well of Enchantments of Binn Edin" (Larminie 1893, pp. 10–30) L

- "Simon and Margaret" (Larminie 1893, pp. 130–138)

- "Beauty of the World" (Larminie 1893, pp. 155–167)

- "The King who had Twelve Sons" (Larminie 1893, pp. 196–210)

- "Cud, Cad, and Micad", (Curtin 1894, pp. 198–222).[26]

- "Coldfeet and Queen of Lonesome Island", (Curtin 1894, pp. 242–261)

- "Art and Balor Beimnech", (Curtin 1894, pp. 312–334). C1

- "Smallhead and the King's Sons" (Jacobs 1894, pp. 80–96 (No.XXXIX); Curtin, contrib. "Hero Tales of Ireland" (New York Sun))

- "The Shining Sword and the Knowledge of the Cause of the One Story about Women" (O'Foharta 1897, pp. 477–92 (ZCP 1))

- "The Snow, Crow, and the Blood" (MacManus 1900, pp. 151–174). This tale closely parallels another collected by Hyde entitled "Mac Riġ Eireann (The King of Ireland's Son)",[27] but in Hyde's version the hero's party obtains "the sword of the three edges" (cloiḋeaṁ na tri faoḃar).

- an untitled tale of Finn's three sons by the Queen of Italy collected at Glenties in Donegal, (Andrews 1919, pp. 91-)

- "An Claidheamh Soluis" (Ó Ceocháin 1927 (Béaloideas I, i (1927), pp. 277–282))

Scottish Gaelic folktales

The publication of tales from the Highlands (Campbell 1860, Popular Tales of the West Highlands) predate the Irish tales becoming available in print. The magic sword sometimes appearing under variant names such as the "White Glave of Light" (Scottish Gaelic: an claidheamh geal soluis).

- "The Young King of Esaidh Ruadh" (Campbell 1860, vol. I, pp.1-, No. 1;)

- "Widow's Son" (Campbell 1860, vol. I, pp.47-, No.2, 2nd variant;)

- "Tale of Conal Crovi" (Campbell 1860, vol. I, pp.125-, No.6; )

- "Tale of Connal" (Campbell 1860, vol. I, p.143-, No.7;)

- "Maol a Chliobain" (Campbell 1860, vol. I, pp.251-, No.17;)

- "The Widow and her Daughters" (Campbell 1860, vol. II, pp.265-, No.41, 2nd variant;)

- "Mac Iain Direach" (Campbell 1860, vol. II, pp.328-, No.46; )

- "An Sionnach, the Fox" (Campbell 1860, vol. II, pp.353-, No.46, 4th variant;)

- "The History of Kitty Ill-Pretts" (Bruford & MacDonald 1994, pp. 185–190, No. 21 )

Mythological interpretations

As a mythological sword

The assertion has been made that Claidheamh Soluis is "a symbol of Ireland attributed in oral tradition to Cúchulainn" (Mackillop[28]), although none of the tales liste above name Cuchulainn as protagonist. T. F. O'Rahilly only went as far as to suggests that the "sword of light" in folk tales was a vestige of divine weapons and heroic weapons, such as Cúchulainn's Cruaidín Catutchenn.[29] This sword (aka "Socht's sword") is said to have "shone at night like a candle" according to a version of Echtrae Cormaic ("Adventures of Cormac mac Airt").[30]

O'Rahilly's schema, roughly speaking, the primeval divine weapon was a fiery and bright lightning weapon, most often conceived of as a throwing spear; in later traditions, the wielder would change from god to hero, and spear tending to be replaced by sword. From the heroic cycles, some prominent are Fergus Mac Roigh's sword Caladbolg and Mac Cecht's spear. But Caladbolg does not manifest as a blazing sword, and the latter which does emit fier sparks is a spear, thus failing to fit the profile of a sword which shines. One example which does fit, is Cúchulainn's sword Cruaidín which was aforementioned. And the legacy of these mythological and heroic weapons survive in the "sword of light" in folklore.[31]

In some circles, the Claidheamh Soluis has been literally been asserted to be the sword of Nuada Airgetlám, one of The Four Treasures of the Tuatha Dé Danann. This notion has become popular in Japan, where this information was disseminated by the fantasy related mythology reference written by Nobuaki Takerube[32] and derivative literature.[lower-alpha 5]

Connection to other swords

Unsurprisingly, some have seen parallels with this to Excalibur, due to some of the descriptions regarding how it shone. When Excalibur was first drawn, in the first battle testing King Arthur's sovereignty, its blade blinded his enemies. Thomas Malory[33] writes: "thenne he drewe his swerd Excalibur, but it was so breyght in his enemyes eyen that it gaf light lyke thirty torchys." Other commentators have equated the Sword of Light to the Grail sword.[34]

Popular culture

Fiction

In fiction, Nuada's sword is to referred to as the Claímh Solais, the sword of light (Book of Conquests (1978), The Silver Arm (1981), and Érinsaga (1985) by artist Jim Fitzpatrick), where it is described as a "rune-engraven" sword.[35]

According Takerube's reference book, Nuadha wore a shining sword called the Claimh Solais (phonetisized Klau-Solas)—fiery sword, sword of light. The Claimh Solais was a magic sword "engraven with spells", and reputedly an Undefeatable Sword such that once unsheathed, no one could escape its blows. And also, it was one of the Four Treasures of Erin brought from the mystical Isle of Findias in the North".[36][37]

See also

References

Explanatory notes

- ↑ The "secret about women" being found also in the Latin G text (Arthur and Gorlagon) his assumption is it was also found in their common ancestor y'.

- ↑ Kennedy's title is identical to a phrase within O'Foharta's title, but Kennedy's translation is inaccurate according to Kittredge.[16]

- ↑ Cf. "Fios-fáh-an-oyn-scéil (the knowledge of the motive of the unique(?) tale)" given in Ó Ceocháin 1928, An Claiḋeaṁ Soluis: agus Fios-fáṫa-'n-aoin-scéil, summary in English, p. 281.

- ↑ In Irish; this is another version of Curtin's " Sculloge's son from Muskerry"[24]

- ↑ Takerube listed Jim Fitzpatrick among his references

Citations

- ↑ Mackillop 1998

- ↑ O'Rahilly 1946, EIHM, p.68; Kennedy

- ↑ Puhvel 1972, p. 214, note27

- ↑ Campbell 1860, I, 24, "The sword of light is common in Gaelic stories;.." etc.

- ↑ "the Divine Hero overcomes his father the Otherworld-god with that god's own weapon, the thunderbolt, known variously in story-telling by names such as the Gaí Bulga (Cú Chulainn's weapon), the Caladbolg (Arthur's Escalibur), or the Claidheamh Soluis of our halfpenny postage-stamps." G.M., review of O'Rahilly 1946(EIHM), in: Studies, an Irish Quarterly Review; Vol. 35, No. 139 (Sep. 1946), pp. 420-422 JSTOR p.421

- ↑ Puhvel (1972), pp. 210, 214–215.

- ↑ Ó hÓgáin (1991), p. 206.

- ↑ Kittredge 1903: Kittredge refers to Morraha, ed. Larminie as I or the Irish folktale version of "the werewolf story" (Arthur and Gorlagon).

- ↑ Campbell 1860, vol. I, 251 (#17)

- ↑ Puhvel 1972, p. 214 : "These are the 'swords of light' or 'glaives of light', usually in the possession of some giant or supernatural 'hag'".

- ↑ Macalister, R.A.S. (2014) [1935], Ancient Ireland: A Study in the Lessons of Archaeology and History, Routledge, p. 75 (original printing: London, Methuen & Co., Ltd., 1935 :"The 'sword of light'.. which made the giants of the fairytales invincible.. is always defeated in the end; the hero, the little man, always succeeds in stealing.. and cutting of its lawful owner's head".

- ↑ Campbell 1860, vol. 1, pp.1-, (No.1)

- ↑ Campbell 1860, vol. II,265 (NO.41)

- ↑ O'Foharta (1897), pp. 477–92.

- ↑ Summary of I in: Kittredge 1903, pp. 217–8

- ↑ Kittredge 1903, p. 218, note 2

- ↑ Larminie (1893), pp. 10–30.

- ↑ Kittredge (1903), p. 163.

- ↑ Kittredge 1903, pp. 163–7 and passim.

- ↑ Day, Mildred Leake (2005), Latin Arthurian Literature, Brewer, p. 42

- ↑ Kittredge (1903), p. 166.

- ↑ Kittredge (1903), pp. 166, 168, 214.

- ↑ Kittredge 1903, pp. 222–230 and seq.

- ↑ Duncan, Leland L. (1894) "Review of The Gaelic Journal Vol. IV \", Folklore 5 (2), pp. 155–157

- ↑ Also see notice in A.C.L. Brown, "Bleeding Lance", PMLA 25, p. 20

- ↑ An Irish text "Cod, Cead agus Mícead was given in An Seaḃac (1932), "Ḋá Scéal ó Ḋuiḃneaċaiḃ", Béaloideas Iml. 3, pp. 381–400. Where it is noted that the storyteller of Curtin's version was found and its Irish version transcribed by Seán Mac Giollarnáth.

- ↑ in Hyde, Douglas (1890), Beside the Fire (Internet Archive), London: David Nutt , pp.18-47. Taken down from Seáġan O Cuineagáin (John Cunningham), village of Baile-an-phuill (Ballinphil), Co. Roscommon, half mile from Mayo. This tale is also closely summarized and analyzed for folk motives by Mackillop 1998, under "King of Ireland's Son"

- ↑ Mackillop 1998, Dict. Celtic Mythol.

- ↑ O'Rahilly 1946, EIHM, p. 68, "Cúchulainn possessed not only the spear of Bulga, but also a sword, known as in Cruaidín Catutchenn, which shone at night like a torch. In folk tales the lightning-sword has survived as "the sword of light" (an cloidheamh solais), possessed by a giant and won from him by a hero."

- ↑ p. 218, in: Stokes, Whitley, ed. tr., Scél na Fír Flatha, Echtra Chormaic i Tír Tairngiri ocus Cert Claidib Chormaic (the Irish Ordeals, Cormac's Adventure in the Land of Promise, and the Decision as to Cormac's Sword ), in Irische Texte III, 1 (Leipzig 1891) pp. 183–229.

- ↑ Puhvel (1972), p. 214.

- ↑ Takerube & Kaiheitai 1990, p. 58

- ↑ Book I, 19, from The Works of Sir Thomas Malory, ed. Vinaver, Eugène, 3rd ed. Field, Rev. P. J. C. (1990). 3 vol. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-812344-2, ISBN 0-19-812345-0, ISBN 0-19-812346-9. (This is taken from the Winchester Manuscript).

- ↑ Nitze, Wm. A. (1909), "The Fisher King in the Grail Romances", PMLA, 24 (3): 406, JSTOR 456840

- ↑ FitzPatrick, Jim (2015) [1978]. "The Book of Conquests". Jim FitzPatrick Gallery. Retrieved January 2016.

Then the second mighty battle-frenzy shook Nuada and again the guise of the Sun-God was his. From the red jewel set in his horned helmet came a dazzling glow of living fire which pulsed and shimmered. In his hand the rune-engraven Claímh Solais, sword of light, turned from dull silver to blood-crimson till it, too, pulsed in time with the jewel

Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ↑ Takerube's book lists Jim Fitzpatrick among its sources.

- ↑ Takerube & Kaiheitai 1990, p. 58; Japanese: 「クラウ・ソラス(Claimh Solais - 炎の剣、光の剣)」と呼ばれる輝く剣を身につけていました。クラウ・ソラスは呪文が刻んである魔剣で、一度鞘から抜かれたら、その一撃から逃れられる者はいない不敗の剣であるとも伝えられています。そしてまた、北方にある神秘島のフィンジアス(Findias)市からもたらされた、エリン四至宝のうちの一つでした。

Bibliography

- Dictionaries

- Mackillop, James (1998), Dictionary of Celtic Mythology, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-280120-1

- Takerube, Nobuaki; Kaiheitai (1990), Koku no kamigami, Truth In Fantasy, 6, Shin kigensha, ISBN 4-915146-24-3 (Japanese: 健部伸明と怪兵隊『虚空の神々』新紀元社)

- Gaelic texts, some with translations

- Kennedy, Patrick, ed. (1866), Legendary Fictions of the Irish Celts, London: Macmillan and Co.

- Campbell, J. F. (1860), Popular Tales of the West Highlands, Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas Vol. I Vol. II)

- Hyde, Douglas (1899), G. Dottin (French tr.), "An Sgeulidhe Gaodhalach XXIX" [The Irish Story XXIX], Annales de Bretagne, 15: 268–291 (Gallica)

- MacInnes, Duncan (1890), Folk and Hero Tales, Alfred Trübner Nutt (notes), Publications of the Folk-lore society, pp. 95–125

- Ó Briain, Pádruig (1889), "Eachtra air an sgolóig agus air an ngruagach ruadh" [Adventure of the Sgolog and the Red Gruagach], Gaelic Journal, 4: 7–9, 26–28, 35–37

- Ó Ceocháin, Domhnall (June 1927), "An Claidheamh Soluis", Béaloideas, 1 (1): 277–

- Ó Ceocháin, Domhnall (June 1928), "An Claiḋeaṁ Soluis: agus Fios-fáṫa-'n-aoin-scéil", Béaloideas, 1 (3): 276–282

- O'Foharta, D. (1897), "An Cloidheamh Soluis Agus Fios Fáth an Aon Sgeil ar na Mnáibh (The Shining Sword and the Knowledge of the Cause of the One Story about Women)", Zeitschrift für celtische Philologie, 1: 477–92

- Translations or tales collected in English

- Andrews, Elizabeth, ed. (1919) [1913], Ulster Folklore, New York: E.P. Dutton (London edition, Elliot Stock, 1913)

- Bruford, Alan J.; MacDonald, Donald A . (1994), Scottish Traditional Tales, Edinburgh: Polygon, pp. 185–190

- Campbell, J. F. (1891), The Celtic Dragon Myth – via Forgotten Books

- Curtin, Jeremiah, ed. (1890), Myths and Folk-Lore of Ireland, Boston: Little, Brown

- Curtin, Jeremiah, ed. (1894), Hero-tales of Ireland, Boston: Macmillan and Company, pp. 198–222, 242–261, 312–334

- Jacobs, Joseph, ed. (1894), More Celtic Fairy Tales, pp. 80–96, 135–155, archived from the original on 2015-10-08

More_Celtic_Fairy_Tales - Larminie, William (1893), West Irish Folk-Tales and Romances, London: Elliot Stock

- Critical studies

- Kittredge, G. L. (1903), Arthur and Gorlagon, Studies and Notes in Philology and Literature, 8, Harvard University, pp. 150–275

- Loomis, Roger Sherman (1997), Celtic Myth and Arthurian Romance, Chicago: Academy Chicago Publishers, pp. 18ff

- Ó hÓgáin, Dáithí (1991), "'Has the Time Come?' (MLSIT 8009): The Barbarossa Legend in Ireland and Its Historical Background", Béaloideas, Iml. 59: 197–207, JSTOR 20522387

- O'Rahilly, T. F. (1946), Early Irish History and Mythology (snippet), Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies

- Puhvel, Martin (1972), "The Deicidal Otherworld Weapon in Celtic and Germanic Mythic Tradition", Folklore, 83 (2): 210–219, JSTOR 1259546

- Popularized versions

- MacManus, Seumas (1900), Donegal Fairy Stories, New York: McClure, Phillips & Co, pp. 157–174