Christian Democratic Party (Norway)

Christian Democratic Party Kristelig Folkeparti | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abbreviation | KrF |

| Leader | Knut Arild Hareide |

| Parliamentary leader | Knut Arild Hareide |

| Founded | 4 September 1933 |

| Headquarters |

Øvre Slottsgate 18–20 0154 Oslo |

| Youth wing | Young Christian Democrats |

| Membership |

|

| Ideology |

Christian democracy[2][3] Social conservatism[3][4] Euroscepticism[5][6] |

| Political position |

Centre to centre-right[7][8][9] [10][11][12][13][14][15] |

| European affiliation | European People's Party (observer) |

| International affiliation | Centrist Democrat International |

| Colours | Yellow |

| Storting |

8 / 169 |

| County Councils[16] |

46 / 728 |

| Municipal / City Councils[17] |

621 / 10,781 |

| Sami Parliament |

0 / 39 |

| Website | |

| www.krf.no | |

The Christian Democratic Party (Bokmål: Kristelig Folkeparti, Nynorsk: Kristeleg Folkeparti, KrF), is a Christian democratic[18][19] political party in Norway founded in 1933. The Norwegian name literally translates to Christian People's Party, shortened KrF. The name may also be translated as "The People's Christian Party".

The party follows its European counterparts in many ways, positioning itself as a family-friendly party. While founded on the basis of advocating moral-cultural Christian issues, the party has broadened its political profile over time, although Christian values remains its core distinction. It is considered an overall centrist party, combining socially conservative views with more left-leaning economic positions.[7] The party is an observer member of the European People's Party (EPP).

The Christian Democrats' leader from 1983 to 1995, Kjell Magne Bondevik, was one of the most prominent political figures in modern Norway, serving as Prime Minister from 1997 to 2000 and 2001 to 2005. Under the old leadership of Bondevik and Valgerd Svarstad Haugland, the party was to some extent radicalized and moved towards the left. Due largely to their poor showing in the 2009 elections, the party has seen a conflict between its conservative and liberal wings.[20] The current leader is Knut Arild Hareide, who has led the party into a more liberal direction as part of a "renewal" process,[21][22] and introduced climate change and environmentalism as the party's most important issues.[23]

Political views

In social policy the Christian Democratic Party generally have conservative opinions. On life issues, the party opposes euthanasia, and abortion, though it may support abortion in cases of rape or when the mother's life is at risk. The party supports accessibility to contraception as a way of lowering abortion rates.[24] They also want to ban research on human fetuses, and have expressed skepticism for proposals to liberalise the biotechnology laws in Norway.[25] Bondevik's second government made the biotechnology laws of Norway among the strictest in the World, with support from the Socialist Left Party and the Centre Party, but in 2004 a case regarding a child with thalassemia brought this law under fire.[26][27] On gay rights issues, the party supports possibilities for gay couples to live together, but opposes gay marriage and gay adoption rights. The party maintains neutrality on the issue of gay clergy, calling that an issue for the church.[28]

Since the party was established, a declaration of Christian faith was required for a person to be a representative in the party. Membership had no such requirement. The increase of support from other religions, including Islam, stimulated efforts to abolish this rule.[29] At the 2013 convention the rule was modified. The new rules require that representatives work for Christian values but do not require them to declare a Christian faith.[30] This latter point was considered the "last drop" for some conservative elements of the party, who as a result broke away and founded The Christians Party.[31]

History

The Christian Democratic Party was founded as a reaction to the growing secularism in Norway in the 1930s. Cultural and spiritual values were proposed as an alternative to political parties focusing on material values. The immediate cause of its foundation was the failure of Nils Lavik, a popular figure in the religious community, to be nominated as a candidate for the Liberal Party, for the parliamentary elections in 1933. In reaction to this, Kristelig Folkeparti was set up, with Lavik as their top candidate in the county of Hordaland. He succeeded in being elected to Stortinget, the Norwegian parliament. No other counties were contested. At the next elections, in 1936, the party also ran a common list with the Libral Party in Bergen, and succeeded in electing two representatives from Hordaland with 20.9% of the local votes.[32] In 1945, at the first elections after the Nazi occupation of Norway, the party was organised on a nationwide basis, and won 8 seats.

The Christian Democrats became part of a short-lived non-socialist coalition government along with the Conservative Party, the Liberal Party and the Centre Party in 1963. At the elections of 1965, these four parties won a majority of seats in Stortinget and ruled in a coalition government from 1965 to 1971.

The Christian Democrats opposed Norwegian membership in the European Community ahead of the referendum in 1972. The referendum gave a no-vote, and when the pro-EC Labour government resigned, a coalition government was formed among the anti-EC parties, the Christian Democrats, the Liberal Party and the Centre Party. Lars Korvald became the Christian Democrats' first prime minister for a year, until the elections of 1973 restored the Labour government.

The party's historic membership numbers peaked with 69,000 members in 1980.[33]

The 1981 elections left the non-socialists with a majority in parliament, but negotiations for a coalition government failed because of disagreement over the abortion issue.[34] However, this issue was later toned down, and from 1983 to 1986 and 1989 to 1990, the Christian Democrats were part of coalitions with the Conservative Party and the Centre Party.

In 1997 the Christian Democrats received 13.7% of the votes, and got 25 seats in the Storting. Kjell Magne Bondevik served as prime minister between 1997 and 2000, in coalition with the Liberal Party and the Centre Party, and then between 2001 and 2005 with the Liberal Party and the Conservative Party.

In the 2005 election the Christian Democrats received only 6.8%, and the party became part of the opposition in the Storting. In 2013 the Conservative Party and the Progress Party formed a new government based on a political agreement with the Christian Democrats and the Liberal party with confidence and supply. In the 2017 election the party got only 4.2% and did not sign a new agreement, but got a politically strategic position as the conservative minority government mainly depended on their votes to get a majority.

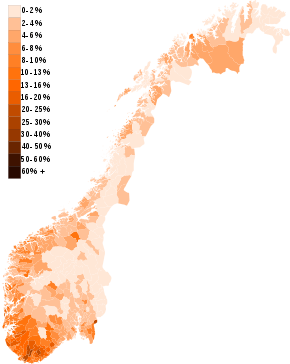

Voter base

Geographically, the Christian Democrats enjoy their strongest support in the so-called Bible Belt, especially in Sørlandet. In the 2005 elections, their best results were in Vest-Agder with 18.9% of the vote, compared to a national average of 6.8%.[35]

As a party centered on Christian values, the party obviously draws support from the Christian population. Their policies supporting Christian values, and opposing same-sex marriage appeal to the more conservative religious base. The main rival in the competition for conservative Christian votes has been the Progress Party,[36] even though it has been claimed that the party has lost some of the more traditionalist and conservative votes to the further-right The Christians, citing an increasing secularisation of the Christian Democratic Party, including the removal of the mandate that party officials must be practicing Christians.[37]

KrF has also sought support among the Muslim minority in Norway, pointing to their restrictive policies on alcohol and pornography, although party's support for Israel concerns some Muslim voters.[38]

Table of parliamentary election results

| Date | Votes | Seats | Size | Notes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | ± pp | # | ± | |||

| 1933 | 10,272 | 0.8 | New | 1 / 150 |

7th | ||

| 1936 | 19,612 | 1.3% | + 0.5 | 2 / 150 |

5th | ||

| 1945 | 117,813 | 7.9% | + 6.6 | 8 / 150 |

6th | ||

| 1949 | 147,068 | 8.4% | + 0.5 | 9 / 150 |

5th | ||

| 1953 | 186,627 | 10.5% | + 2.1 | 14 / 150 |

4th | ||

| 1957 | 183,243 | 10.2% | - 0.3 | 12 / 150 |

5th | ||

| 1961 | 171,451* | 9.6%* | - 0.6 | 15 / 150 |

4th | government 1963 | |

| 1965 | 160,331* | 8.1%* | - 1.5 | 13 / 150 |

5th | government 1965– | |

| 1969 | 169,303* | 9.4%* | + 1.3 | 14 / 150 |

4th | government –1971, 1972–73 | |

| 1973 | 255,456* | 12.3%* | + 2.9 | 20 / 155 |

4th | ||

| 1977 | 224,355* | 12.4%* | + 0.1 | 22 / 155 |

3rd | ||

| 1981 | 219,179* | 9.4%* | - 3.0 | 15 / 155 |

3rd | government 1983– | |

| 1985 | 214,969 | 8.3% | - 1.1 | 16 / 157 |

3rd | government –1986 | |

| 1989 | 224,852 | 8.5% | + 0.2 | 14 / 165 |

5th | government 1989–90 | |

| 1993 | 193,885 | 7.9% | + 0.6 | 13 / 165 |

5th | ||

| 1997 | 353,082 | 13.7% | + 5.8 | 25 / 165 |

3rd | government 1997–2000 | |

| 2001 | 312,839 | 12.4% | - 1.3 | 22 / 165 |

5th | government 2001–05 | |

| 2005 | 178,885 | 6.8% | - 5.6 | 11 / 169 |

5th | ||

| 2009 | 148,748 | 5.5% | - 1.3 | 10 / 169 |

3rd | ||

| 2013 | 158,475 | 5.6% | + 0.1 | 10 / 169 |

4th | ||

| 2017 | 122,688 | 4.2% | - 1.4% | 8 / 169 |

7th | ||

- * The Christian Democratic Party ran on joint lists with other parties in a few constituencies from 1961 to 1981. Vote numbers are from independent Christian Democratic lists only, while vote percentage also includes the Christian Democratic Party's estimated share from joint lists (Statistics Norway estimates).[39]

List of party leaders

- Ingebrigt Bjørø (1933–38)

- Nils Lavik (1938–51)

- Erling Wikborg (1951–55)

- Einar Hareide (1955–67)

- Lars Korvald (1967–75)

- Kåre Kristiansen (1975–77)

- Lars Korvald (1977–79)

- Kåre Kristiansen (1979–83)

- Kjell Magne Bondevik (1983–95)

- Valgerd Svarstad Haugland (1995–2004)

- Dagfinn Høybråten (2004–11)

- Knut Arild Hareide (2011–present)

Further reading

- Madeley, John T.S. (2004). Steven Van Hecke; Emmanuel Gerard, eds. Life at the Northern Margin: Christian Democracy in Scandinavia. Christian Democratic Parties in Europe Since the End of the Cold War. Leuven University Press. pp. 217–241. ISBN 90-5867-377-4.

References

- ↑ "KrF og Venstre mistet over 2.000 medlemmer på ett år". Dagens Næringsliv (in Norwegian). 11 January 2018.

- ↑ Hans Slomp (2011). Europe, A Political Profile: An American Companion to European Politics. ABC-CLIO. p. 425. ISBN 978-0-313-39182-8.

- 1 2 Nordsieck, Wolfram (2017). "Norway". Parties and Elections in Europe. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ↑ "Norway - Political parties". Norwegian Social Science Data Services. Retrieved 27 January 2010.

- ↑ Madeley, John (2013). "Religious Euroscepticism in the Nordic countries: modern or pre-/anti-/post- modern?". In François Foret, Xabier Itçaina. Politics of Religion in Western Europe: Modernities in conflict?. Routledge. p. 152. ISBN 9781136636400.

- ↑ Skinner, Marianne S. (2010). "Political Culture, Values and Economic Utility: A Different Perspective on Norwegian Party-based Euroscepticism". Journal of Contemporary European Research. University of Bath. 6 (3): 299–315.

- 1 2 Allern, Elin Haugsgjerd (2010). Political Parties and Interest Groups in Norway. ECPR Press. pp. 183–186. ISBN 9780955820366.

- ↑ "Sentrum – politikk". Store norske leksikon. 10 October 2013.

- ↑ Van Hecke, Steven; Gerard, Emmanuel (2004). Christian Democratic Parties in Europe Since the End of the Cold War. Leuven University Press. p. 231. ISBN 9789058673770.

- ↑ Love, Juliet; O'Brien, Jillian, eds. (2002). Western Europe 2003. Europa Publications. p. 493. ISBN 9781857431520.

- ↑ Narud, Hanne Marthe; Esaiasson, Peter, eds. (2013). Between-Election Democracy: The Representative Relationship After Election Day. ECPR Press. p. 86. ISBN 9781907301988.

- ↑ Bergqvist, Christina (1999). Equal Democracies?: Gender and Politics in the Nordic Countries. Nordic Council of Ministers. p. 320. ISBN 9788200127994.

- ↑ Müller, Wolfgang C.; Strom, Kaare. Coalition Governments in Western Europe. Oxford University Press. p. 169. ISBN 9780198297611.

- ↑ Kotkas, Toomas; Veitch, Kenneth (2016). Social Rights in the Welfare State: Origins and Transformations. Taylor & Francis. p. 50. ISBN 9781315524320.

- ↑ The Statesman's Yearbook 2017: The Politics, Cultures and Economies of the World. Palgrave Macmillan. 2017. p. 917. ISBN 9781349683987.

- ↑ "Valg 2011: Landsoversikt per parti" (in Norwegian). Ministry of Local Government and Regional Development. Archived from the original on 24 September 2011. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- ↑ "Kristeleg Folkeparti". Valg 2011 (in Norwegian). Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- ↑ Oyvind Osterud (2013). Norway in Transition: Transforming a Stable Democracy. Routledge. pp. 114–. ISBN 978-1-317-97037-8.

- ↑ T. Banchoff (28 June 1999). Legitimacy and the European Union. Taylor & Francis. pp. 126–. ISBN 978-0-415-18188-4. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ↑ Gjerde, Robert (15 February 2010). "Nestleder vil skrote KrFs Israel-politikk". Aftenposten. Stavanger.

- ↑ "Eriksen: – Vi er ein offensiv gjeng". NRK. 30.04.2011. "Den nye leiartrioen skal føre Krf gjennom ei fornyingsfase fram mot stortingsvalet i 2013. Eriksen har leia partiet sitt strategiutval og står bak ei rekkje forslag som vil trekkje KrF i meir liberal retning."

- ↑ "KrF-Hareide: - Ja, jeg har fått meg kjæreste". VG. 26.04.2011.

- ↑ Dropper å gå i regjering – satser på miljø

- ↑ KrF on life protection and abortion Archived 2009-02-26 at the Wayback Machine. (KrF.no) (in Norwegian)

- ↑ KrF on bio- and genetic technology Archived 2009-02-25 at the Wayback Machine. (KrF.no) (in Norwegian)

- ↑ Mehmet gets stem-cell dispensation Aftenposten, December 10, 2004

- ↑ Stillheten etter Mehmet (The quiet after Mehmet) VG, September 1, 2005

- ↑ KrF on gay rights Archived 2009-02-25 at the Wayback Machine. (KrF.no) (in Norwegian)

- ↑ Sporstøl, Ellen (May 2, 2009). "Høybråten ønsker seg muslimer" (in Norwegian). TV2 nyhetene. Archived from the original on March 17, 2014. Retrieved 2009-09-02.

- ↑ Grøttum, Eva-Therese; Johnsen, Nilas. "Nå har KrF droppet kristenkravet". Dagbladet (in Norwegian). 26 April 2013. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ↑ http://snl.no/De_Kristne

- ↑ NORGES OFFISIELLE STATISTIKK IX. 107., "Official statistics IX.107 of Norway"

- ↑ Røed, Lars-Ludvig (7 January 2009). "Lengre mellom partimedlemmene i dag". Aftenposten. Archived from the original on 2010-12-30.

- ↑ National Archival Services of Norway Archived 2007-10-09 at the Wayback Machine. (in Norwegian)

- ↑ "Stortingsvalet 2005. Godkjende røyster, etter parti/valliste og kommune. Prosent" (in Norwegian). Statistisk sentralbyrå. 2005. Retrieved 2009-09-02.

- ↑ Fondenes, Eivind (September 1, 2009). "- Høybråten tjener på homo-motstand". TV2 nyhetene. Retrieved 2009-09-02.

- ↑ Sæle, Finn Jarle. "Hvorfor kristenfolket vinner - om de taper KrF (Why Christian people win - if they lose the Christian Democratic Party)". idag.no. IDAG. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- ↑ Archer, Else Karine (August 14, 2009). "Tror på Allah, stemmesanker for KrF" (in Norwegian). NRK. Retrieved 2009-09-02.

- ↑ http://www.ssb.no/a/histstat/tabeller/25-3.html