Choking

| Choking | |

|---|---|

| |

| A demonstration of abdominal thrusts on a person showing signs of choking | |

| Specialty | Emergency medicine |

Choking (also known as foreign body airway obstruction) is a life-threatening medical emergency characterized by the blockage of air passage into the lungs secondary to the inhalation or ingestion of food or another object.[1] Choking is caused by a mechanical obstruction of the airway that prevents normal breathing. This obstruction can be partial (allowing some air passage into the lungs) or complete (no air passage into the lungs). The disruption of normal breathing by choking deprives oxygen delivery to the body, resulting in asphyxia. Although oxygen stored in the blood and lungs can keep a person alive for several minutes after breathing stops,[2] this sequence of events is potentially fatal. Choking was the fourth most common cause of unintentional injury-related death in the US in 2011.[3]

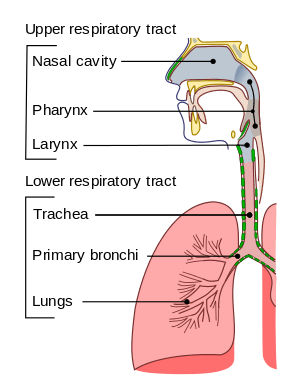

According to the National Safety Council, deaths from choking most often occur in the very young (children under 1 years old) and in the elderly (adults over 75 years).[1] Obstruction of the airway can occur at the level of the pharynx or the trachea. Foods that can adapt their shape to that of the pharynx (such as bananas, marshmallows, or gelatinous candies) can be a danger not just for children but for persons of any age.[4]

Choking is one type of airway obstruction, which includes any blockage of the air-conducting passages, including blockage due to tumors, swelling of the airway tissues, and compression of the laryngopharynx, larynx or vertebrate trachea in strangulation.

Symptoms and signs

- Difficulty or inability to speak or cry out

- Inability or difficulty in breathing . Labored breathing, including gasping or wheezing may be present

- Violent and largely involuntary coughing, gurgling, or vomiting noises may be present

- More serious choking victims will have a limited (if any) ability to produce these symptoms since they require at least some air movement.

- The person may begin clutching of the throat or mouth, or attempting to induce vomiting by putting fingers down the throat

- The person's face turns blue (cyanosis) from lack of oxygen, if breathing is not restored.

- The person may become unconscious, if breathing is not restored.

Complications

- Brain damage typically occurs if the body is deprived of air for three minutes.

- Death will usually occur if breathing is not restored in six to eight minutes.

Cause

Choking is caused by an object from outside the body, also called a foreign body, blocking the airway.[5] The object can block the upper or lower airway passages.[6] The airway obstruction is usually partial but can also be complete.[6]

Among children, the most common causes of choking are food, coins, toys, and balloons.[5] In one study, peanuts were the most common object found in the airway of children evaluated for suspected foreign body aspiration.[7] Foods that pose a high risk of choking include hot dogs, hard candy, nuts, seeds, whole grapes, raw carrots, apples, popcorn, peanut butter, marshmallows, chewing gum, and sausages.[5] The most common cause of choking death in children is latex balloons.[5] Small, round non-food objects such as balls, marbles, toys, and toy parts are also associated with a high risk of choking death because of their potential to completely block a child's airway.[5]

Children younger than age three are especially at risk of choking because they explore the environment by putting objects in their mouth.[5] Also, young children are still developing the ability to chew food completely.[5] Molar teeth, which come in around 1.5 years of age, are necessary for grinding food.[5] Even after molar teeth are present, children continue developing the ability to chew food completely and swallow throughout early childhood.[5] In addition, a child's airway is smaller in diameter than an adult's airway, which means that smaller objects can cause an airway obstruction in children. Infants and young children generate a less forceful cough than adults, so coughing may not be as effective in relieving an airway obstruction.[5] Finally, children with neuromuscular disorders, developmental delay, traumatic brain injury, and other conditions that affect swallowing are at an increased risk of choking.[5]

In adults, choking often involves food blocking the airway.[8] Risk factors include using alcohol or sedatives, undergoing a procedure involving the oral cavity or pharynx, wearing oral appliances, or having a medical condition that causes difficulty swallowing or impairs the cough reflex.[8] Conditions that can cause difficulty swallowing and/or impaired coughing include neurologic conditions such as strokes, Alzheimer disease, or Parkinson disease.[9] In older adults, risk factors also include living alone, wearing dentures, and having difficulty swallowing.[8]

Children and adults with neurologic, cognitive, or psychiatric disorders may experience a delay in diagnosis because there may not be a known history of a foreign body entering the airway.[8]

Prevention

Providers such as pediatricians and dentists can provide information to parents and caregivers about what food and toys are appropriate by age to prevent choking.[5] The American Academy of Pediatricians recommends waiting until 6 months of age before introducing solid foods to infants.[10] Caregivers can supervise children while eating or playing.[11] Also, caregivers can avoid giving children younger than 5 foods that pose a high risk of choking such as hot dog pieces, cheese sticks, cheese chunks, hard candy, nuts, grapes, marshmallows, or popcorn.[11] Parents, teachers, child care providers, and other caregivers for children get training in choking first aid and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).[5]

In the US, manufacturers of children's toys and products must follow requirements to prevent choking and include appropriate warning labels.[5] However, toys that are resold may not be marked with warning labels.[5] Caregivers can try to prevent choking by considering the features of a toy (such as size, shape, consistency, small parts) before giving it to a child.[5] Children's products that are found to pose a choking risk can be recalled.[5]

Treatment

Choking is treated with a number of different procedures, with both basic techniques available for first aiders and more advanced techniques available for health professionals.

Basic treatment

Basic treatment of choking includes a number of non-invasive techniques to help remove foreign bodies from the airways. Most modern protocols, including those of the American Heart Association and the American Red Cross, recommend several stages, designed to apply increasingly more pressure. For the conscious choking victim, most protocols recommend encouraging the victim to cough, followed by hard back slaps and if none of these things work; abdominal thrusts (Heimlich maneuver) or chest thrusts. Once the choking victims loses consciousness, initiating CPR is recommended.[12]

Cough

If the choking individual is conscious and coughing, the American Red Cross recommends encouraging the individual to continue coughing. The American Red Cross recommends that if the person choking is unable to cough or if coughing is not effective, to move onto other methods, detailed below.[13]

Back Blows (or Slaps)

The Mayo Clinic recommends the use of back blows to aid in the rescue of choking victims. Back blows are performed by leaning the choking victim forward, then delivering blows with the heel of the hand onto the victim's back, in between their shoulder blades.[14] If back blows are performed, they must be performed with the head lower than the chest (i.e., bend the person over when you slap them hard between the shoulder blades with the heel of the palm); otherwise, the blow may drive the object deeper into the person's throat.

Abdominal Thrusts (Heimlich Maneuver)

Abdominal thrusts are performed with the rescuer standing behind the person choking and exerting inward and upward pressure with their hands on the choking person's abdomen. This method of dislodging an airway obstruction was discovered by Dr. Henry Heimlich in 1974 and, when used alone (without back blows) to assist a choking victim, is referred to as "The Heimlich Maneuver." The purpose of abdominal thrusts is to create pressure that will expel any object lodged in the airway upwards to relive the obstruction. The Heimlich Maneuver specifically excludes back blows; its inventor, Dr. Henry Heimlich, believed that back blows were likely to cause an airway obstruction to become more deeply lodged in the victim's airway. So, while abdominal thrusts are part of other choking victim protocols, the Heimlich Maneuver uses only abdominal thrusts to attempt to dislodge airway obstructions.

"Five and Five" Technique

The American Red Cross recommends a strategy of alternating five back blows and five abdominal thrusts for conscious choking victims until the object blocking the airway is dislodged. Chest thrusts are advised for pregnant or obese victims. If the person choking becomes unconscious, basic CPR is recommended.[13] Although the Red Cross does not specifically refer to its choking victim protocol as the "Five and Five Technique," it is important to recognize that the Red Cross protocol differs from the Heimlich Maneuver since it includes administering back blows to the victim, contrary to Dr. Heimlich's procedure which specifically omits back blows.

Finger Sweep

If the choking victim becomes unconscious, the American Medical Association advocates sweeping the fingers across the back of the throat to attempt to dislodge airway obstructions,[15] However, many modern protocols recommend against the use of the finger sweep. Red Cross procedures specifically direct rescuers not to perform a finger sweep unless an object can be clearly seen in the victim's mouth due to the risk of driving the obstruction deeper into the victim's airway. Other protocols suggest that if the patient is conscious they will be able to remove the foreign object themselves, or if they are unconscious, the rescuer should simply place them in the recovery position as this allows (to a certain extent) the drainage of fluids out of the mouth instead of down the trachea due to gravity. There is also a risk of causing further damage (for instance inducing vomiting) by using a finger sweep technique. There are no studies that have examined the usefulness of the finger sweep technique when there is no visible object in the airway. Recommendations for the use of the finger sweep have been based on anecdotal evidence.[12]

Self-treatment

The Heimlich Maneuver (abdominal thrusts) can be performed or can be self-administered. Self-administration of this maneuver requires positioning of one's own abdomen over a chair, railing, or countertop and driving the abdomen upon the object with sharp, upward thrust. This serves as a substitute for thrusts made with the hands by another person. One study showed that these self-administered abdominal thrusts were just as effective as those performed by another person, although obese individuals were not included in the study.[16] Self-assist choking devices are another self-treatment option. This device is used to produce the inward and upward force of traditional abdominal thrusts. Multiple sources of evidence suggest, that one of promising approaches for self treatment during choking could be by applying the head-down (inversed) position.[12]

Special treatment populations

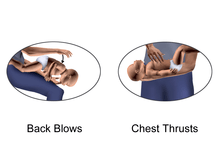

Infants (Less than 1 year)

For children less than 1 year, the American Heart Association recommends performing cycles of 5 back blows (or slaps) followed by 5 chest compressions.[17] These cycles of 5 back blows then 5 chest compressions are repeated until the object comes out of the infant's airway or until the infant becomes unresponsive.[17] If the infant becomes unresponsive, the American Heart Association recommends starting CPR.[17] The reason that abdominal thrusts are not recommended in children less than 1 year is because they can cause liver damage.[17]

Pregnant or Obese Persons

The American Heart Association recommends chest thrusts rather than abdominal thrusts for pregnant or obese persons who are choking.[12] Chest thrusts are performed in a similar to the abdominal thrusts, but with a change in hand placement of the rescuer. The hands are placed on the lower part of the choking victim's chest, at the base of the breastbone or sternum, rather than over the middle of the abdomen, as in traditional abdominal thrusts. Strong inward thrusts are then applied.[14]

Advanced treatment

There are many advanced medical treatments to relieve choking or airway obstruction. These include inspection of the airway with a laryngoscope or bronchoscope and removal of the object under direct vision. Severe cases where there is an inability to remove the object may require cricothyrotomy (emergency tracheostomy). Cricothyrotomy involves making an incision in a patient's neck and inserting a tube into the trachea in order to bypass the upper airways.[18] The procedure is usually only performed when other methods have failed. In many cases, an emergency tracheostomy can save a patient's life, but if performed incorrectly, it may end the patient’s life.

Epidemiology

Choking is the fourth most common cause of unintentional injury-related death in the US.[3] Many episodes are not reported because they are brief and resolve without seeking medical attention.[5] Among reported events, the majority of episodes (80%) occur among children younger than age 15, with fewer episodes (20%) among age 15 and older.[3] The death rate from choking is low at most ages but increases starting around age 74.[3] Choking due to a foreign object resulted in 162,000 deaths (2.5 per 100,000) in 2013, compared to 140,000 deaths (2.9 per 100,000) in 1990.[19]

Notable cases

- The former President of the United States, George W. Bush, survived choking on a pretzel on January 13, 2002, an event that received major media coverage.[20]

- Jimmie Foxx, a famous Major League Baseball player, died by choking on a bone.[21]

- Tennessee Williams, the playwright, reportedly died after choking on a bottle cap.[22]

- Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother notably experienced three major choking incidents where a fish bone became lodged in her throat: initially on 21 November 1982, when she was taken from Royal Lodge to the King Edward VII Hospital for an operation at 3am;[23] secondly in August 1986 at Balmoral, when she was taken to the Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, though no operation was needed;[23] and in May 1993, when she was admitted to the Aberdeen Infirmary once again for an operation under general anaesthetic.[24]

- Air Marshal Subroto Mukerjee, the first Chief of the Air Staff of the Indian Air Force (IAF), died on 8 November 1960 at Tokyo by choking on a piece of food lodged in his windpipe.[25]

- Dr Henry Heimlich, the inventor of the Heimlich maneuver (abdominal thrust technique) saved a fellow retirement home resident from choking in late May 2016, at the age of 96.[26]

- Praful Bidwai, an Indian journalist and activist, died by choking on food on 23 June 2015 at a conference in Amsterdam.[27]

- American rapper Prodigy of Mobb Deep died by accidental choking.[28]

See also

References

- 1 2 Council., National Safety. Injury facts. National Safety Council. Research and Statistics Department. (2015 ed.). Itasca, IL. ISBN 9780879123345. OCLC 910514461.

- ↑ Ross, Darrell Lee; Chan, Theodore C (2006). Sudden Deaths in Custody. ISBN 978-1-59745-015-7.

- 1 2 3 4 "Injury Facts 2015 Edition" (PDF). National Safety Council. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ↑ Sayadi, Roya (May 2010). Swallow Safely: How Swallowing Problems Threaten the Elderly and Others (First ed.). Natick, MA: Inside/Outside Press. pp. 46–47. ISBN 9780981960128.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Committee on Injury, Violence (2010-03-01). "Prevention of Choking Among Children". Pediatrics. 125 (3): 601–607. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-2862. ISSN 0031-4005. PMID 20176668.

- 1 2 Dominic Lucia; Jared Glenn (2008). CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment: Emergency Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-184061-3.

- ↑ Yadav, S. P.; Singh, J.; Aggarwal, N.; Goel, A. (September 2007). "Airway foreign bodies in children: experience of 132 cases". Singapore Medical Journal. 48 (9): 850–853. ISSN 0037-5675. PMID 17728968.

- 1 2 3 4 Warshawsky, Martin (31 December 2015). "Foreign Body Aspiration". Medscape. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ↑ Boyd, Michael; Chatterjee, Arjun; Chiles, Caroline; Chin, Robert. "Tracheobronchial Foreign Body Aspiration in Adults". Southern Medical Journal. 102 (2): 171–174. doi:10.1097/smj.0b013e318193c9c8.

- ↑ "Infant Food and Feeding". www.aap.org. Retrieved 2017-12-15.

- 1 2 "Choking Prevention for Babies". Safe Kids Worldwide. Retrieved 2017-12-15.

- 1 2 3 4 "Part 5: Adult Basic Life Support and Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Quality – ECC Guidelines". eccguidelines.heart.org. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- 1 2 "STEP 3: Be Informed - Conscious Choking | Be Red Cross Ready". www.redcross.org. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- 1 2 "Choking: First aid". Mayo Clinic. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ↑ American Medical Association (2009-05-05). American Medical Association Handbook of First Aid and Emergency Care. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-0712-7.

- ↑ Pavitt MJ, Swanton LL, Hind M; et al. (12 April 2017). "Choking on a foreign body: a physiological study of the effectiveness of abdominal thrust manoeuvres to increase thoracic pressure". Thorax: 576–578. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-209540.

- 1 2 3 4 Wilkins, Lippincott Williams & (2010-11-02). "Editorial Board". Circulation. 122 (18 suppl 3): S639–S639. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181fdf7aa. ISSN 0009-7322.

- ↑ "What is a trahceostomy?". Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ↑ GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators (17 December 2014). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385: 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- ↑ "Bush makes light of pretzel scare". BBC News. 2002-01-14. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- ↑ "Jimmie Foxx Obituary". Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- ↑ "Biography of Tennessee Williams". IMDB. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- 1 2 Vickers, Hugo (2005). Elizabeth, the Queen Mother. London: Hutchinson. p. 449. ISBN 0-09-180010-2.

- ↑ "Queen Mother recovers after operation". BBC News. 1999-01-25. Retrieved 2009-08-22.

- ↑ "The Saga of a Soaring Legend". www.indianairforce.nic.in. IAF. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ↑ Walters, Joanna (2016-05-27). "Dr Henry Heimlich uses Heimlich manoeuvre for first time at 96". the Guardian. Retrieved 2016-06-07.

- ↑ Praful Bidwai#cite note-4

- ↑ {{Cite web|url=https://www.nydailynews.com/entertainment/mobb-deep-rapper-prodigy-died-accidental-choking-article-1.3382073%7Ctitle=Mobb Deep rapper Prodigy died of accidental choking

External links

| Classification |

|---|