Chieti

| Chieti | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Comune | |||

| Città di Chieti | |||

.jpg) Panorama of Chieti | |||

| |||

| Motto(s): Theate Regia Metropolis utriusque Aprutinae Provinciae Princeps | |||

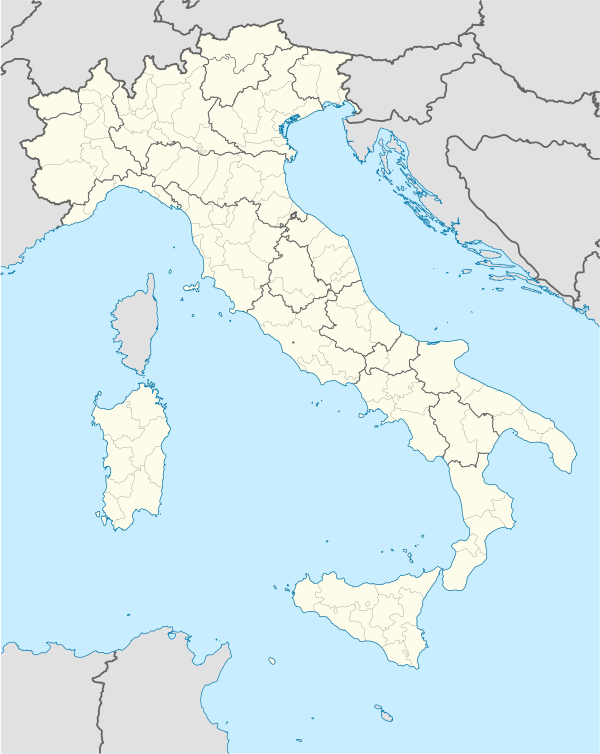

Chieti Location of Chieti in Italy | |||

| Coordinates: 42°21′N 14°10′E / 42.350°N 14.167°ECoordinates: 42°21′N 14°10′E / 42.350°N 14.167°E | |||

| Country | Italy | ||

| Region | Abruzzo | ||

| Province | Chieti (CH) | ||

| Frazioni | Bascelli, Brecciarola, Buonconsiglio-Fontanella, Carabba, Cerratina, Chieti Scalo, Colle dell'ara, Colle Marcone, Crocifisso, De Laurentis Vallelunga, Filippone, Fonte Cruciani, Iachini, La Torre, Madonna del Freddo, Madonna della Vittoria, Madonna delle Piane, San Martino, San Salvatore, Santa Filomena, Selvaiezzi, Tricalle, Vacrone Cascini, Vacrone Colle San Paolo, Vacrone Villa Cisterna, Vallepara, Villa Obletter, Villa Reale | ||

| Government | |||

| • Mayor | Umberto Di Primio (FI) | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 58.55 km2 (22.61 sq mi) | ||

| Elevation | 330 m (1,080 ft) | ||

| Population (31 December 2017)[1] | |||

| • Total | 50,770 | ||

| • Density | 870/km2 (2,200/sq mi) | ||

| Demonym(s) | Teatini | ||

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) | ||

| Postal code | 66100 | ||

| Dialing code | 0871 | ||

| Patron saint | St. Justin of Chieti | ||

| Saint day | May 11 | ||

| Website | Official website | ||

Chieti (Italian: [ˈkjeːti] (![]()

In Italian, the adjectival form is teatino and inhabitants of Chieti are called teatini. The English form of this name is preserved in that of the Theatines, a Catholic religious order.

History

Chieti is amongst the most ancient of Italian cities. According to mythological legends, the city was founded in 1181 BC by the Homeric Greek hero Achilles and was named in honor of his mother, Thetis. It was called Theate (Greek: Θεάτη) (or Teate in Latin). As Theate Marrucinorum, Chieti was the chief town of the warlike Marrucini. According to Strabo, it was founded by the Arcadians as Thegeate (Θηγεάτη).

After the Marrucini were defeated by the Romans, they became loyal allies of the more powerful forces. Their territory was placed under Roman municipal jurisdiction after the Social War. In imperial times, Chieti's population reached 60,000 inhabitants but, after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, it was destroyed by Visigoths and Heruli. Later it was seat of a gastaldate under the Lombard kings. After its destruction by Peppin, it became a fief of the Duchy of Benevento.

Chieti recovered some political and economic importance under the Norman rule of Southern Italy, a role it kept also under the Hohenstaufen, Angevine and Aragonese rulers. After a cultural and architectural flourishing during the 17th century, under the aegis of the Counter-Reformation, Chieti was decimated by fatalities from plague in 1656. In the 18th century, several new academies and schools were developed here, which contributed to the city's artistic heritage. In 1806 Chieti was turned into a fortress by Napoleon's France. In 1860 it became part of the newly created Kingdom of Italy.

During World War II, Chieti was declared an open city (like Rome) and was not bombed by either side. It was the site of an infamous POW Camp for British and Commonwealth officers (PG 21) where its commandante – Barela – was later convicted of war crimes for his treatment of POWs. Imprisonment in wartime Italy was tough enough. At some camps conditions were much harder, and the regime more brutal, than at others.

PG 21 was a very large camp through which many POWs passed, often on their way to other camps such as Veano and Fontanellato. It was overcrowded, with little running water, poor sanitation and, in winter, no heating. Shortage of food and warm clothing prompted debate in the UK House of Commons.

The story of the camp between August 1942 and September 1943 is told in a book published in November 2014 and written by Brian Lett, a former chairman of the Monte San Martino Trust and the author of several books, including S.A.S. in Tuscany. He tells of suffering under a violently pro-Fascist regime. The first Commandant personally beat up one recaptured escapee. A pilot was murdered by an Italian guard following his escape attempt. Tunnels were dug, and the prisoners were even prepared to swim through human sewage to try to get out. Somehow, morale remained remarkably high.

After the war, a number of the camp’s staff were arrested for war crimes, concluding its unhappy history.[2] The city at this time welcomed many refugees from the near towns and villages. Allied forces liberated the city on June 9, 1944, one day after the Germans left the city.

Geography

Chieti is situated a few kilometers away from the Adriatic Sea, and with the Majella and Gran Sasso mountains in the background. It is divided into the old town on the homonymous hill overlooking the Aterno-Pescara and the more recent commercial and industrial area, which is called Chieti Scalo and has developed thanks to the Chieti railway station along the ancient layout of Via Tiburtina, in the valley of the Aterno-Pescara.[3][4]

Architecture

-dome.jpg)

The cathedral dedicated to Saint Justin of Chieti was probably founded in the 8th century and, according to tradition, was re-built by bishop Teodorico I in 840, after the sack by Pepin of Italy. It was again re-built by bishop Attone I in 1069,[5][6] but of that building only parts of the Romanesque crypt remain. The church was beautified in the 14th and 15th centuries thanks to different bishops. The first three floors of the bell tower were erected in 1335 by Bartolomeo di Giacomo and in 1498 Antonio da Lodi built its bellcote and tented roof. The church was decorated again in the 17th century in the Baroque style. The 1703 Apennine earthquakes destroyed the tented roof of the bell tower and damaged the church, whose aspect was changed by the archbishop Francesco Brancia between 1764 and 1770. In the early 20th century the architect Antonio Cirilli consolidated the bell tower and extensively modified the exterior. The crypt hosts the relics of Saint Justin of Chieti.[5][6][7] Close to the cathedral there is the Baroque oratory of the Mount of the Dead Brotherhood, the oldest catholic fraternity of Chieti that was officially acknowledged by Pope Innocent X in 1648.[8]

The Church of Saint Francis, which has the traditional Latin cross plan, was probably founded in 1239 thanks to the nobleman Antonio Gizio, who donated his estate to the project. In the second half of the 14th century a new façade was constructed, but it was rebuilt in the 17th century except the top with a rose window. After years of decay, in 1689 they started an extensive restoration which changed the aspect of this church. At the end of the 19th century the architect Torquato Scaraviglia added an external stairway and another intervention was commissioned by the noblewoman Theresa de Hortalis, but at the moment it is again under restoration due to damage from the 2009 L'Aquila earthquake. The church has an hemispherical dome with trompe-l'œil paintings and ten chapels, whose improvements were financed by some of the most important and ancient families of Chieti.[9][10]

The Baroque Church of Saint Clare was built for the nuns of the Order of Saint Clare between 1644 and 1720.[11]

The Teatro Marrucino (Italian for "Marrucinian Theatre") was built between 1813 and 1818 in the Neoclassical style and in 1872 the Neapolitan artist Giovanni Ponticelli painted the front curtain, representing the triumph over Dalmatae of Gaius Asinius Pollio.[12]

Ancient Roman architecture

There are different Roman sites in Chieti, including three temples, a theatre, an amphitheatre, thermae and underground cisterns.

In the area of La Civitella there are the remains of a Roman theatre, which was probably built in the 1st century CE, a period of prosperity. The building had a diameter of about 80 meters and could host about 5,000 spectators, but today they can see little more than the left wing of its cavea with some corridors.

In 1935 Desiderato Scenna discovered the remains of four ancient Roman temples, the best-preserved one of which was used as a church since the 8th century and renamed after Saint Peter and Saint Paul, whereas another one has been removed to build a post office. The construction of the two twin temples and the smaller one was commissioned by Marcus Vetius Marcellus and his wife Helvidia Priscilla, who were favored by Nero. They do not know what divinities they were dedicated to, even if some scholars proposed that they were consecrated to the Capitoline Triad (Jupiter, Juno and Minerva). The walls are made of bricks, marble slabs, stone slabs and stone tiles, and the plan of the twin temples included a portico and underground spaces.[13][14]

The thermae are connected to an underground cistern, which is a part of a complex Roman water supply system. In addition, underneath the 18th-century Palazzo de' Mayo there is the so-called via tecta, an over 4 meters tall ancient Roman underground street, whose function is still debated.[15][16][17][18]

Climate

Chieti climate is considered genuine Mediterranean. It presents high humidity all year round, with rainy/snowy warm winters and hot and dry summers. Rain is a common event, especially during fall and spring, with accumulations of around 600 to 700 millimetres (24 to 28 in) a year. Snowfall is consistent during winter, with temperatures that often drop below 0 °C (32 °F) during winter nights. Fog is a common event during fall and winter, due to very high humidity in these seasons. Wind from the north-east (from the Adriatic sea) carries cold from Eurasian Steppe, while wind from south-west (from the Tyrrhenian Sea) carries hot from Algerian Desert. Wind is quite present during year.

| Climate data for Chieti, at the University | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 22.1 (71.8) |

26.5 (79.7) |

28.1 (82.6) |

32.0 (89.6) |

35.1 (95.2) |

37.5 (99.5) |

39.7 (103.5) |

41.7 (107.1) |

40.3 (104.5) |

30.2 (86.4) |

27.6 (81.7) |

24.8 (76.6) |

41.7 (107.1) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 12.3 (54.1) |

12.9 (55.2) |

16.0 (60.8) |

20.0 (68) |

24.2 (75.6) |

28.7 (83.7) |

32.1 (89.8) |

31.6 (88.9) |

27.0 (80.6) |

21.1 (70) |

17.4 (63.3) |

13.2 (55.8) |

21.3 (70.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 8.2 (46.8) |

8.6 (47.5) |

11.4 (52.5) |

15.0 (59) |

18.8 (65.8) |

23.0 (73.4) |

26.3 (79.3) |

25.6 (78.1) |

21.8 (71.2) |

16.7 (62.1) |

13.0 (55.4) |

8.8 (47.8) |

16.4 (61.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 4.2 (39.6) |

4.4 (39.9) |

6.8 (44.2) |

10.0 (50) |

13.5 (56.3) |

17.4 (63.3) |

20.5 (68.9) |

19.7 (67.5) |

16.6 (61.9) |

12.3 (54.1) |

8.7 (47.7) |

4.5 (40.1) |

11.5 (52.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −4.9 (23.2) |

−3.9 (25) |

−2.7 (27.1) |

0.9 (33.6) |

6.3 (43.3) |

9.3 (48.7) |

13.4 (56.1) |

11.5 (52.7) |

7.9 (46.2) |

3.1 (37.6) |

0.4 (32.7) |

−5.3 (22.5) |

−5.3 (22.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 53.4 (2.102) |

57.0 (2.244) |

67.0 (2.638) |

52.8 (2.079) |

59.5 (2.343) |

44.3 (1.744) |

45.8 (1.803) |

21.3 (0.839) |

72.5 (2.854) |

67.0 (2.638) |

75.9 (2.988) |

43.6 (1.717) |

660.5 (26.004) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 8.3 | 8.3 | 8.5 | 8.0 | 7.8 | 5.0 | 3.1 | 3.3 | 6.5 | 8.2 | 7.1 | 6.3 | 80.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 76.9 | 73.2 | 70.7 | 70.1 | 66.5 | 64.4 | 60.1 | 63.5 | 70.0 | 78.8 | 78.9 | 75.2 | 70.6 |

| Source: Chieti Meteo[19] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1861 | 19,586 | — |

| 1871 | 24,762 | +26.4% |

| 1881 | 22,248 | −10.2% |

| 1901 | 26,343 | +18.4% |

| 1911 | 26,897 | +2.1% |

| 1921 | 31,381 | +16.7% |

| 1931 | 33,905 | +8.0% |

| 1936 | 30,266 | −10.7% |

| 1951 | 40,534 | +33.9% |

| 1961 | 47,792 | +17.9% |

| 1971 | 51,436 | +7.6% |

| 1981 | 54,927 | +6.8% |

| 1991 | 55,876 | +1.7% |

| 2001 | 52,486 | −6.1% |

| 2011 | 51,484 | −1.9% |

| 2016 | 51,330 | −0.3% |

| Source: ISTAT[20][1] | ||

According to the statistics conducted by Istat, in 2016 people aged 0–19 totaled 15.5% of the population compared to people aged 65 and over who number 25.0%.[21] In 2016 4.6% of the population (2.397 people) consisted of non-Italians with Romanians (677 people), Albanians (505) and Ukrainians (137) that were the largest immigrant groups.[22] According to a study of the Ministry of Economy and Finance, in 2016 the median income for a household in the town was €23,996.[23]

Economy

The agriculture has remained an important economic sector thanks to horticulture, cereal cultivation, olive cultivation, cultivation of tobacco and cultivation of grapes, from which are made well-known wines, such as Montepulciano d'Abruzzo and Trebbiano d'Abruzzo. Financial services, trade and industry are developed, especially in the production of food, chemicals, paper, building material, packaging, engineering industry and metallurgy. In addition, Chieti hosts the seat of the homonymous province, a television station (Rete 8), hospitals, sport venues and different hotels.[24][25]

Education

Chieti has different state and private kindergartens, different state primary and middle schools, a private secondary school (the D.O.G.E. School College) and 7 state secondary schools: Istituto "Luigi di Savoia" (1529 students), Istituto tecnico "Galiani-De Sterlich", Liceo "Isabella Gonzaga", Liceo scientifico "Filippo Masci", Istituto "Umberto Pomilio", Liceo classico "G.B. Vico" and Liceo artistico statale.[26]

The University of Chieti (Università G. d'Annunzio – Chieti e Pescara) is based in Chieti and Pescara and hosts about 35,000 students, covering areas of Architecture, Arts and Philosophy, Economics, Foreign Languages and Literatures, Management, Medicine, Pharmacy, Psychology, Sciences, Social Sciences and Sports Medicine.

Culture

According to some historians, the Good Friday procession, which is considered Italy's oldest religious procession, has taken place in Chieti since 842. From historical documented sources, the origins of its current form date back to the 16th century. It is organized by the Mount of the Dead Brotherhood, an old local fraternity, with different sacred symbols, such as a wooden figure of Christ and a mourning Virgin Mary. Hooded adults and children, a choir and an orchestra playing Miserere by Saverio Selecchy (a local composer of the 18th century) takes part in the event.[27][28][29][30]

The Abruzzese dialect, which is considered by some linguists a separate language, is still spoken in Chieti.[31]

Museums

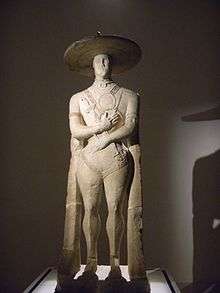

- The National Archaeological Museum of Abruzzo is surrounded by an urban park and is located in the former 19th-century Neoclassical residence of the Frigerj family. The rooms of the museum, which hosts the ancient Warrior of Capestrano, are dedicated to: Italic sculpture, Roman sculpture, a numismatic collection, a collection of antiquities created by Giovanni Pansa, the Vestini, the Peligni, the Marrucini and the Carricini.[32][33]

- The Archaeological Museum La Civitella is close to the Roman amphitheatre and is focused on the Marrucini and the ancient history of Chieti.[34]

- The University Museum of History of Biomedical Sciences is managed by the University of Chieti-Pescara and exposes prehistoric finds, rocks, minerals, a malacological collection, medical devices of the early 20th century and a collection of contemporary art. The museum is located in the former local house of the Opera Nazionale Dopolavoro, an example of fascist architecture.[35]

- The art museum dedicated to Costantino Barbella is located in an 18th-century palace and houses frescoes, sculptures, paintings, and pottery from the 15th to the 20th centuries, including a collection of Maiolica from Castelli.[36]

- The Museo Diocesano Teatino (Italian for "Diocesan Museum of Chieti") is located in the 17th-century Church of Saint Dominic and hosts frescoes from the 14th to the 16th century, wooden statues and paintings.[37]

Transport

The public transport bus service of Chieti is provided by companies Società Unica Abruzzese di Trasporto and La Panoramica, which manages also the Chieti trolleybus system. The territory between Pescara and Chieti is crossed by two motorways, the Autostrada A14 Bologna-Taranto and the Autostrada A25 Roma-Pescara.

Chieti Scalo is crossed by the Rome–Sulmona–Pescara railway and has two train stations, the Chieti railway station and the smaller Chieti–Madonna delle Piane railway station. A railway connecting the old town and Chieti Scalo was closed in 1943.[38]

Chieti is about 12 kilometers from the Abruzzo Airport and 17 kilometers from the Port of Pescara.[4][39]

Notable people

- Herius Asinius - Commander of the Marrucini

- Gaius Asinius Pollio (75 BC / AD 4) – Roman soldier, politician, orator, poet, playwright, literary critic and historian

- Saint Justin of Chieti

- Severino Di Giovanni – Anarchist who exiled himself to Argentina in 1922

- Ferdinando Galiani – Economist

- Sergio Marchionne – Former CEO of Ferrari and Fiat Chrysler Automobiles

- Alessandro Valignano – Jesuit missionary who helped the introduction of Catholicism to the Far East

- Pierluigi Zappacosta – Co-founder of Logitech, Venture Partner with Noventi, President/CEO of Sierra Sciences

- Luciano Odorisio – Actor, movie director

- Costantino Barbella - Sculptor

Gallery

- The Church of Saint Dominic

_-_Interior.jpg) The Church of Saint Clare

The Church of Saint Clare- Corso Marrucino, the main street of the old town, and the dome of the Church of Saint Francis

.jpg) Teatro Marrucino

Teatro Marrucino.jpg) Roman theatre

Roman theatre Roman thermae

Roman thermae Remains of a Roman amphitheater

Remains of a Roman amphitheater%2C_an_ancient_Roman_underground_passage.jpg) Via Tecta, an ancient Roman underground street

Via Tecta, an ancient Roman underground street- A pediment of a temple in the Archaeological Museum La Civitella

The National Archaeological Museum of Abruzzo surrounded by the urban park

The National Archaeological Museum of Abruzzo surrounded by the urban park

See also

References

- 1 2 "Popolazione Chieti 2001-2016" (in Italian). tuttitalia.it. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ↑ An Extraordinary Italian Imprisonment: The Brutal Truth of Campo 21, 1942–3 by Brian Lett QC

- ↑ Chieti at Encyclopædia Britannica

- 1 2 "Localizzazione di Chieti" [Location of Chieti] (in Italian). italapedia.it. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- 1 2 Gasbarri, Camillo. "Description of Chieti cathedral" (in Italian). GUTE&BERG. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- 1 2 "Chiesa Cattedrale di San Giustino" [Cathedral Church of Saint Justin] (in Italian). Comune of Chieti. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ↑ "San Giustino di Chieti" [Saint Justin of Chieti] (in Italian). santiebeati.it. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ↑ Gasbarri, Camillo. "Description of the oratory" (in Italian). GUT&BERG. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ↑ "Chiesa di San Francesco d'Assisi" [Church of Saint Francis of Assisi] (in Italian). Comune of Chieti. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ↑ Gasbarri, Camillo. "Description of Church of Saint Francis" (in Italian). GUT&BERG. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ Gasbarri, Camillo. "Description of Church of Saint Clare" (in Italian). GUTE&BERG. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ↑ "Teatro Marrucino" (in Italian). Comune of Chieti. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ↑ "Tempietti romani" [Roman temples] (PDF) (in Italian). Fondo Ambiente Italiano. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ "Visitando il museo" (PDF) (in Italian). Archaeological museum La Civitella. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ "Chieti" (in Italian). portaleabruzzo.com. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ↑ Orsini, Errico. "Sotterrnaei di Chieti" [Subterranea of Chieti] (in Italian). Centro Appenninico Ricerche Sotterranee. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ↑ Orsini, Errico. "Sotterranei di Chieti" [Subterranea of Chieti] (in Italian). Centro Appenninico Ricerche Sotterranee. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ↑ "Chieti sotterranea" [Subterranea of Chieti] (in Italian). Speleoclub Chieti. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ "Chieti Meteo". Retrieved 2010-08-11.

- ↑ "Censimenti popolazione Chieti 1861-2011" (in Italian). tuttitalia.it. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Popolazione per età, sesso e stato civile 2016" (in Italian). tuttitalia.it. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Cittadini stranieri Chieti 2016" (in Italian). tuttitalia.it. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ↑ Tronca, Filippo (May 5, 2016). "I redditi abruzzesi: prima Pescara, L 'Aquila seconda e sempre più ricca" (in Italian). AbruzzoWeb. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Economia di Chieti" [Economy of Chieti] (in Italian). Italiapedia.it. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Home page" (in Italian). Rete8. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Schools in Chieti" (in Italian). Ministry of Education, Universities and Research. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- ↑ Lebedeva, Anna. "Chieti's Moving Good Friday Easter Procession". italychronicles.com. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ↑ "A brief history of the Procession". Mount of the Dead Brotherhood. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ↑ "Saverio Selecchy" (in Italian). Mount of the Dead Brotherhood. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ↑ "In Italy, Discovering an Ancient Good Friday All-Female Rite with a Fashion Twist About It (and a Message for All Men...)". Irenebrination: Notes on Architecture, Art, Fashion, Fashion Law & Technology. Retrieved 2018-04-01.

- ↑ Abruzzese dialect - by Roberta D’Alessandro (Italian) on YouTube

- ↑ "Villa Frigeri" (in Italian). Comune of Chieti. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ↑ "Description of the museum". Archaeological superintendence of Abruzzo. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ↑ "Description of the museum La Civitella". Archaeological superintendence of Abruzzo. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ↑ "Collezioni" [Collections] (in Italian). University of Chieti-Pescara. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ↑ "C. Barbella Art Museum". Welcome to Italy S.r.l. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ↑ "Diocese Theatin Museum". Welcome to Italy S.r.l. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ↑ "Ferrovia Chieti Stazione - Chieti Citta'" (in Italian). ferrovieabbandonate.it. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Come arrivare a Chieti" [How to get to Chieti] (in Italian). informagiovani-italia.com. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

Sources

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Chieti. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chieti. |

- Site of National Museum Archaeological of Abruzzi Villa Frigerii

- Official site of Biomedical Museum

- Official site of Archaeological Museum "La Civitella"

- Official site of Art Museum "Costantino Barbella"

- Italy's most important Easter Procession in Chieti

- Photo Gallery (in Italian)