Chang and Eng Bunker

| Chang and Eng Bunker | |

|---|---|

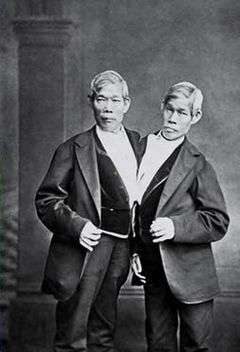

Eng (viewer's left) and Chang in later years | |

| Born |

May 11, 1811 Samut Songkhram, Thailand |

| Died |

(aged 62) Mount Airy, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Cause of death |

Chang: cerebral blood clot Eng: fright? See § Autopsy |

| Resting place |

White Plains Baptist Church 36°27′13″N 80°37′44″W / 36.4536°N 80.6288°W[1] |

| Nationality | Siamese and American |

| Years active | 1829–1870 |

| Known for | Exhibitions as curiosities, known as the "Siamese twins" |

| Spouse(s) |

Chang: Adelaide Yates Eng: Sarah Yates (both m. 1843–1874) |

| Children |

Chang: 11 Eng: 10 |

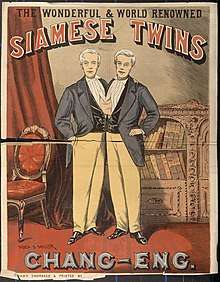

Chang and Eng Bunker (May 11, 1811 – January 17, 1874) were Siamese-American conjoined twin brothers, popularly known as the "Siamese twins", the name they used to promote themselves. Their fame propelled the expression to become a synonym for conjoined twins in general.

Born in today's Thailand with Chinese heritage, the brothers were brought to the United States in 1829. Within three years they left the control of their managers, who they thought were cheating them, and toured on their own. Many physicians studied them as they became known to American and European audiences in "freak shows". Newspapers and the public were sympathetic to them but not immune to racial prejudice. In early exhibitions, they appeared exotic and displayed their athleticism; later on, in a more dignified parlor setting, they would hold conversations in English.

After a decade of financial success, the twins quit touring in 1839 and settled near Mount Airy in rural North Carolina. Integrating into the community, they became U.S. citizens, married local sisters, and bought slaves. They fathered 21 children, several of whom would accompany them once they resumed touring a decade later. The families lived in two separate houses, alternating three-day stays. The twins became well-off businessmen; after the Civil War they lost the part of their wealth in slaves. An autopsy after their death at the age of 62 revealed that their livers were fused in the ligament connecting their sternums.

Many works have fictionalized the Bunkers' lives or use them to symbolize cooperation or discord, such as representing the Union and Confederacy during the Civil War. Novelist Darin Strauss wrote, "No definitive history of the twins' life exists; their conjoined history was a confusion of legend, sideshow hyperbole, and editorial invention even while they lived."[2]

Life in Siam (1811–1829)

Chang and Eng[nb 1] were born in 1811 in Siam (now called Thailand); their mother reportedly said their birth was no more difficult than their siblings'.[3] Their exact date of birth and details of their early lives are unknown; the earliest report on the twins assigns the birth month of May 1811.[4][nb 2] Their birth village is called Meklong; a statue in the province of Samut Songkhram commemorates the twins' birthplace.[5]

Their father, Ti-eye, was a fisherman of Chinese descent. He died when the twins were young, possibly in a smallpox epidemic in 1819. Their mother, Nok, raised ducks with her children's help.[6] Her ethnic origin is unclear; varying accounts suggest that she was Siamese, Chinese, part-Chinese and part-Siamese, or part-Chinese and part-Malay.[7][nb 3] Chang and Eng believed in Siamese Buddhism, and despite being joined at the sternum were lively children, running and playing with others.[8] Their mother raised them like her other children, in a "matter-of-fact" way that did not put special attention on their being conjoined.[9]

The "discovery" of the brothers is credited to the British merchant Robert Hunter.[10] Hunter was a trusted trade associate of the Siamese government and traveled with considerable freedom. In 1824, Hunter reportedly first met the twins while he was on a fishing boat in the Menam River and the twins were swimming at dusk. He mistook them for a "strange animal", but after meeting them he saw economic opportunity in bringing them to the West.[11][nb 4] He went to tell a story that the king of Siam had ordered the brothers' death and forbidden him to transport them out of the country; regardless of the story's veracity, it took five years for Hunter to bring them away.[12] Hunter and American sea captain Abel Coffin departed to the United States with the twins in summer 1829, and a contract Hunter and Coffin signed with the brothers stipulated that their tour would last for five years.[13] A rumor later circulated that the twins' mother had sold them into slavery, a charge which greatly upset them.[14] Christian missionaries contacted her in 1845, four years before she died. She had believed that her conjoined sons were dead, having not seen them for fifteen years, but was informed that they were alive and recently married.[15][nb 5]

Travel and touring (1829–1839)

Chang and Eng were 17 years old when they traveled to the United States with Hunter, Coffin, a crew of eighteen men, and a Siamese translator.[17] They arrived in Boston on August 16, 1829, and the next day the Boston Patriot confirmed Coffin and Hunter's ambitions: the twins "will probably be exhibited to the public".[18] They were soon inspected by physicians, many of whom employed physiognomy and phrenology and judged them to be Chinese, and their arrival was excitedly reported with varying degrees of racial stereotypes and falsehoods.[19]

After leaving the United States, they toured major cities in England, and by the time they returned to New York in March 1831, the twins had gained some skill in English reading, writing, and speaking. Newspapers reported that they had earned great profits, and their promotional materials began to describe their customers as dignified—though their act of exhibition could seem crude—to help bring more moneyed visitors.[20]

When touring in cities, the twins stayed at a hotel for several days, sometimes for more than a week, and charged audiences to attend their "freak show". In small towns, their manager would send flyers ahead of their arrival, and they would remain at a lodge or inn for just one or two nights.[21] Their first manager, James W. Hale, introduced the twins as the "Siamese Youths", a name they preferred to "boys." The usual admission price was 25 cents, equivalent to $6 in 2017, and pamphlets and drawings featuring the brothers were also usually for sale. In early performances, the twins performed physical feats, running and doing somersaults. An emphasis was placed on their exoticness: they wore pigtails and dressed in "Oriental" clothing. They occasionally exhibited swimming, playing checkers, and doing parlor tricks.[22]

Conflicts on tour

In the summer of 1831, Hale took the twins on a retreat in Lynnfield, Massachusetts. While hunting game, they were approached by over a dozen local men and thought they were being taunted and harassed, going on to strike a man named Elbridge Gerry with the butt of their gun. Gerry retaliated, throwing a heavy stone at one twin's head, drawing blood. The twins fired at Gerry, though their gun was blank. The men ran off. The following day, one of the men pressed charges, alleging that the twins were at fault. A special court was convened, and the brothers were arrested for disturbing the peace and paid bond for good behavior.[23]

The Salem Mercury portrayed the twins as the victims of the Lynnfield incident; other papers followed suit. Two weeks after the event, Gerry published a letter titled "To the Public", saying that the twins had provoked the violence. Hale became mad that the twins had gotten into a situation where their public image could be slandered. He resigned as their manager in September 1831 and was replaced by a friend, Charles Harris.[24] Hale counseled Harris on such matters as how to avoid paying the Virginia exhibition tax through careful marketing: he would call the twins' tour a "business", not a "show". In the public eye, Abel Coffin, the man who first brought them to the United States, continued to serve as a father figure to the twins.[25]

The twins were involved in another conflict soon later, during a performance in Alabama. A surgeon in attendance rose to ask to conduct a close examination of the ligature connecting the twins. They refused, having not permitted close inspections for more than two years. Rising in anger—"you are all a set of impostors and pickpockets," the doctor said—disorder erupted as guests threw objects across the room. The twins fled and later, as they were probably the first ones to disturb the peace, paid a good-behavior bond ordered by a magistrate.[26]

Relations between the twins and the Coffins strained beginning in January 1831, when Abel's wife Susan Coffin refused requests from the twins on several issues. Later in the year, Chang and Eng started asking Harris to send letters pleading their cases. In one instance, Mrs. Coffin refused the twins an additional $3 per week to feed their horse, an act the twins compared to clipping a bird's wings and saying, "Now you may fly if you wish." Harris first maintained a distinction between his and the twins' point of view but eventually wrote using their voice and had them sign their names "Chang Eng".[27]

Abel Coffin left for Asia in late 1831 and planned to return by January 1832.[28] After January passed the twins' relations with Mrs. Coffin broke down completely. They regularly asked about when Abel Coffin would get back once; they hoped to be free from commitment to the Coffins on their 21st birthday (in May 1832) as Abel had once promised. They also worried that, should Coffin never return, they would remain in permanent limbo between freedom and contract. They began to think that Mrs. Coffin was "deceitful and greedy" as they learned of the Coffins' management practices. Mrs. Coffin had encouraged them to perform when they were sick. During one voyage, the Coffins had paid full fare for themselves but booked the twins into steerage, listing them as servants, and lied to the twins when they were questioned. The twins learned that Mrs. Coffin was willing to pay a higher wage for one attendant than for the one the twins preferred. They came to believe that Mrs. Coffin "had misled me".[29]

Independent travel

Abel Coffin returned to Massachusetts in July 1832 and discovered that the twins were missing. He accused Hale of "exciting his subjects to rebellion" (Hale had not) and eventually tracked down the brothers in Bath, New York. Hale later said that Coffin said he had met the twins "whoring, gaming, and drinking" and "gave Chang Eng 'the damndest thrashing they ever had in their lives.'" Coffin simply wrote to his wife as follows: "We have had much talk; they seem to feel themselves quite free from me."[30]

The twins did not immediately announce that they were in business on their own nor alter their public persona.[31] Their relationship had once been essentially indentured servitude; with freedom, they hired staff and were in command of their act.[32] They were now exclusively referred to by their stage name, the "Siamese twins", and changed parts of their performance, such as by wearing American clothes, speaking English with the audience, and presenting themselves no longer as "boys" but men. They answered audience questions sitting in a formal, parlor setting. In their free time, they hunted game.[33]

They did not perform on their sightseeing trip across Western Europe in 1835–36 visiting Paris; Antwerp, Belgium; The Hague and Amsterdam, and other cities. In 1836, Hale published a pamphlet titled A Few Particulars concerning Chang-Eng, the United Siamese Brothers, Published under Their Own Direction. Among other particulars positioning the twins as upper-class—such as explaining that Chinese were elites in Siam—it reported that a representative of United States president Andrew Jackson had visited the twins' mother.[34]

Settled and later life (1839–1874)

Traphill

The final setting for the Chang and Eng's on-and-off 1829–1839 tour was held in Jefferson, North Carolina, on July 3 and 4, 1839. According to a family friend, moving to Wilkes County, in the northwest of the state, allowed them to "engage in chasing stag and catching trout ... to enjoy the recreation which they had desired to find far away from the hurrying crowds."[35] In October 1839, they purchased 150 acres (61 ha) for $300, equivalent to $6,894 in 2017, near the rural community of Traphill, in mountainous northeast Wilkes County. The tract runs along Little Sandy Creek, near the Roaring River.[36]

They soon became well acquainted with members of elite Wilkes society, including James Calloway and Robert C. Martin, physicians; Abner Carmichael, the county sheriff; and James W. Gwyn Jr., the county's superior court clerk. Former manager Charles Harris relocated with them, becoming postmaster of Traphill.[37][nb 6] The month they bought the land, the twins and Irish-born Harris became naturalized citizens. Gwyn administered their oath of allegiance; despite a federal law from 1790 restricting naturalization to "free white persons," citizenship was a matter generally governed by local attitudes.[38][nb 7][nb 8]

A home on the Traphill land was constructed in 1840.[39] The brothers bought foodstuffs from Wilkes slaveholders and traded dry goods with their neighbors. They also bought slaves and hired several women as housekeepers; the twins' first slave was named "Aunt" Grace Gates.[40] Prosperous from their time touring, they displayed their wealth through elegant house decoration; by the early 1840s, their property was the third-most valuable in the county at $1,000, equivalent to $24,513 in 2017.[41] They planned to stop exhibiting for good, content to live in Traphill. The Whig Party newspaper Carolina Watchman of Salisbury called them "genuine Whigs," and the Boston Transcript reported that they were "happy as lords."[42]

Raleigh Register

April 13, 1853[43]

In 1840, a profile of the twins in the Tennessee Mirror made clear the twins' intentions to marry. Many newspapers regularly joked about such an act, discouraging marriage not just with objections over the twins' deformity but because of their race.[44] Nevertheless, on April 13, 1843, Baptist preacher Colby Sparks officiated the weddings between Eng and Sarah Yates, and between Chang and Adelaide Yates. Though national (mainly Northern) newspapers generally condemned the marriages, there was probably little local reaction except purported vandalism of Sarah and Adelaide's parent's house the night before the wedding.[45][nb 9] The Bunkers featured their marriages prominently when they would go on tour in later life.[46]

By the late 1840s, the twins spoke English fluently, had voted, and had filed criminal charges against several white people.[47] They had also adopted the English-language surname Bunker, in honor of a woman whom they met in New York and admired.[48] Continued newspaper coverage as visitors flocked to their Traphill home established them as national celebrities. They felt themselves to be Americans.[47] The Bunkers carved a unique place in Americans' perception of race—they were considered nonwhite but afforded many of the privileges of whiteness as Southern slaveholders with property rights.[49]

Mount Airy

On March 1, 1845, the Bunkers bought a plot of 650 acres (260 ha) in Surry County. They had a home built—at first just for part-time use—about 5 miles (8 km) south of Mount Airy, along Stewart's Creek.[39] The twins amassed great wealth during the late 1840s and 1850s and lived in luxury as plantation owners. In 1850, it was estimated that they had invested $10,000 in property in North Carolina, equivalent to $294,160 in 2017. A merchant in New York managed another $60,000 for importing, equivalent to $1,764,960 in 2017, and they lived off the interest.[50]

They split their time between Mount Airy and Traphill because their families had grown large; by 1847 Adelaide had delivered four children and Sarah three.[39] They maintained the Traphill residence through 1853, though later their time was divided solely between two homes around Mount Airy.[51] In their living arrangement for the next decades, the twins alternated which house they used three days at a time; the twin who owned the current house was allowed to choose whatever they wanted to do while the other twin kept silent.[52]

In 1850, ten of their eighteen slaves were under the age of seven, some owned just to be sold later for profit, and some grew up to work the fields. The Bunker plantations produced wheat, rye, corn, oats, and potatoes, and raised cows, sheep, and pigs. That they did not grow tobacco—unlike many North Carolina farms—may suggest that their plantation was run primarily to feed the Bunker family and its slaves.[53] The press characterized the Bunkers' treatment of slaves as particularly harsh, though the twins decried charges of cruelty and said that their wives supervised the slaves and raised money for their education.[54][nb 10]

Despite being generally part of the region's aristocracy, some of their practices set them apart. They were occasionally seen performing manual labor. Their method of chopping wood was particularly effective: they wielded the ax with all four hands for more force or rapidly took turns swinging. They continued recreational hunting, and they took up fishing, drinking, and several sports.[55]

Return to touring

.jpg)

Partial retirement ended up not suiting the Bunkers, and they sought to resume touring for what they called financial reasons: they needed to earn more money to support their then seven children. They traveled to New York City in 1849 with daughters Katherine and Josephine, both aged five, but the brief tour petered out due to poor management, and they returned to North Carolina. Advertisements read, "The Living Siamese Twins Chang-Eng and Their Children."[56]

They conducted a successful year-long tour in 1853, again bringing two children (Christopher and Katherine). They again justified the tour by saying their motivation was to raise money to support their (by this point, 11) children's education.[56] On this tour, viewings were sort of levees and were not elaborate, as the twins and their children usually sat, spoke, and mingled with the audience. They wore American suits and spoke in English about their marriages and families and also showed off their wit and political knowledge.[57] They appeared educated and polite, according to biographer Joseph Andrew Orser, and "the Bunkers might have appeared as a distinguished southern family on display except for the fact that no family of distinction would exhibit itself to the public."[58]

In early October 1860 they signed with famed showman P. T. Barnum for a month and exhibited in Barnum's American Museum in New York City. They performed alongside Zip the Pinhead and for several distinguished guests, including the Prince of Wales; in 1868, they briefly toured with him in England.[59] Contrary to popular belief, the Bunkers' careers were not created by Barnum, their competitor in the entertainment business: the twins had already become world-famous from their tours.[60]

They departed New York City on November 12, took steamships, and crossed Panama by train to arrive in San Francisco on December 6.[61] California politics was figuring out how to deal with an influx of Chinese immigrants, putting the arrival of the twins (and two of Eng's sons, Patrick and Montgomery) in the spotlight. As usual, the Bunkers were favorably received by audiences with whom they spoke, though reports of performances in the state took various perspectives on their race and nationality. Newspapers called them "yellow" but also the "greatest of living curiosities" who had "made much noise in the world, and are certainly worth seeing."[62] They left California on February 11, 1861, by which time seven states had seceded from the United States, triggering the American Civil War. The Bunkers likely returned to their Mount Airy homes by mid-April—after gunfire had begun in South Carolina but before North Carolina's secession on May 20.[63]

Civil War metaphor

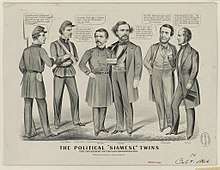

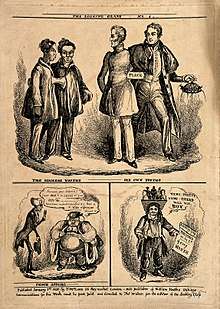

This cartoon objects to the 1864 Democratic ticket that combined two men with differing views: George Pendleton opposed the Civil War; George McClellan did not support a ceasefire.[64]

Throughout the Civil War, the twins' conjoined state served in several metaphors.[63] In July 1860, the Louisville Journal chided divisions in the Democratic Party by making the twins out to be rival factions within the party, split on the extent to which slavery should be federally protected. The Bunker brothers, however, were long-time supporters of the Whig Party, and a neighbor wrote to The Fayetteville Observer that they "are not now and never have been Democrats [and] they say they never expect to be Democrats." The neighbor said that both twins supported the Tennessean John Bell of the Constitutional Union Party in the 1860 presidential election, a candidate popular in northwestern North Carolina, whose platform included both preservation of the Union and slavery.[65]

More prominently, many newspapers fictitiously wrote that Chang and Eng were at odds with each other on the issue of secession, personifying fears of sectional violence.[66][nb 11] The New-York Tribune ran a colorful allegory that claimed to be an account of a dispute between the twins while they were at Barnum's American Museum. It said that Chang, the quarrelsome one, wanted the ligament connecting them to be painted black (signifying the key issue of slavery) but Eng did not. Chang said that his "union" with Eng was to be "dissolved", and a "Dr. Lincoln" [President Lincoln] reasoned that a separation surgery would be "dangerous for both parties."[67]

According to Orser, "The united brothers had become symbols the American union and the promise it offered to its citizens."[68] Orser adds that reports of conflict between the Bunkers carried some truth: the brothers had legally separated their property, land and slaves, and had created separate wills, formalizing the manner had lived in since marriage.[69]

Final years

By the time the Civil War ended in 1865, the twins' finances had taken a hit (they had lent money that was repaid in worthless Confederate currency) and their slaves were emancipated, so they decided to resume touring. Northern audiences at this point were not so receptive to the twins—they had been Confederate slaveholders—so during tours they presented themselves sympathetically as old men with many children who only reluctantly supported their state over country, and who each had a son hurt in the war (serving in the Confederate States Army), one injured and one captured.[71] Newspapers disparagingly wrote that the twins had lost "a considerable number of slaves of about the same color of themselves" and that they were taking advantage of their audience.[70]

They made a trip to Britain in 1868–69 and saw physicians and chatted as an exhibit; their last visit there had been over thirty years before. Along came Chang's daughter Nannie, who had never before been far from home, and Eng's daughter Kate, both in their twenties. The trip led them from North Carolina to Baltimore and New York, then across the Atlantic to Liverpool and into rural Scotland, later seeing Manchester.[72] In 1870, Chang, Eng, and two sons went to Germany and Russia; they wanted to further explore Europe but returned home to avoid the developing Franco-Prussian War. On the ship back home, Chang's right side (near Eng) became paralyzed after he suffered a stroke, and they effectively retired as Eng cared for Chang. The Bunker estate in 1870 was worth a total $30,000—two-thirds belonging to Chang—equivalent to $580,579 in 2017.[73]

Family

.jpg)

Sarah Yates Bunker was born on December 18, 1822, the fourth child and second daughter of David and Nancy Yates.[74] Sometimes called "Mrs. Eng," she was seen as the simpler sister and, uneducated, lived frugally and was a capable chef. She was described as the "more portly, fair one."[75] Both sisters outlived their husbands; Sarah died at age 69 on April 29, 1892.[76]

Adelaide Yates Bunker, or "Mrs. Chang," was born on October 11, 1823.[74] Taller and thinner than her older sister, she "excelled in personal beauty" and was seen as having a more refined taste. It was said that both Chang and Eng favored Sarah; however, according to a contemporary newspaper, "To any but an oriental taste, [Adelaide] was much the prettiest, being, in fact, a handsome and showy brunette."[75] She died at age 93 on May 21, 1917.[76]

Chang's and Eng's first children were born within six days of each other. Sarah gave birth to Katherine Marcellus on February 10, 1844, and Adelaide to Josephine Virginia on February 16. One set of cousins was born eight days apart: Chang's son Christopher and Eng's daughter Julia. Chang and Adelaide had ten children; Eng and Sarah had eleven. Altogether, there were twelve daughters and nine sons. Two were deaf, and two died from burns before age three. None were twins.[77]

The twins occasionally attended church with their wives.[78] For some time in the 1850s, the family moved to Mount Airy for the children to be formally educated by two clergymen. Later, a schoolhouse was built on the Mount Airy property and they hired a tutor.[79]

Today, direct descendants of Chang and Eng's 21 children number over 1,500.[80] Much of the extended family still lives in western North Carolina (some say they "look real Bunkery" i.e., Asian), and they have hosted annual get-togethers since the 1980s, usually on the last Saturday of June.[81] Chang's descendants include grandson Caleb V. Haynes, an Air Force major general and his son Vance Haynes, an archaeologist;[82] great-granddaughter Alex Sink, former Chief Financial Officer of Florida and the Democratic nominee for Governor of Florida in 2010;[83] and great-great-granddaughter Caroline Shaw, a composer and the 2013 Pulitzer Prize for Music recipient.[84] Eng's descendants include grandson George F. Ashby, president of the Union Pacific Railroad in the 1940s.[85] The Bunker pedigree contains eleven sets of twins, none conjoined; the first set of twins, Eng's great-grandsons, were also named Chang and Eng.[86]

Medical condition and death

At birth, Chang and Eng were healthy xiphopagus twins connected by a flexible circular band of flesh at the sternum, about 5 inches (130 mm) long with a maximum circumference of 9 inches (230 mm).[87] Their livers were connected through the band, and only at the middle of the ligament did they share sensation.[88][nb 12]

Most physicians who met the twins recommended against surgery for separation; it would have been a fatal procedure.[86] Contemporary medical literature suggests that the twins could have been separated.[89] The surgeon who performed their autopsy, William Pancoast of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania's Jefferson Medical College, believed that the twins should have been separated even considering the chance of one twin's death because of the possibility of "improper relations between the wives and the brothers" and said that he would have performed the operation himself given the chance.[90]

While Eng enjoyed good health toward the end of his life, most of Chang's right side became paralyzed in 1870 after his stroke, and eventually his right leg needed to be kept in a sling. The rest of his life, Chang—becoming a heavy drinker—remained in poor health.[91] Chang contracted bronchitis in January 1874, and the family physician recommended that he stayed indoors and warm. On January 15, the Bunkers traveled through cold weather to Eng's house. Chang seemed to have recovered somewhat by the next day but at night was unable to breathe comfortably. On Chang's urging they slept sitting upright on a chair in front of the fireplace. Eng was healthy physically yet weary from spending the past week with Chang seriously ill, so he asked to move to their bed after hours of drifting in and out of sleep.[52]

The story of their death goes that early in the morning of January 17, one of Eng's sons checked on the sleeping twins. "Uncle Chang is dead," the boy said to Eng, who responded, "Then I am going!" The family doctor was quickly sent for but soon Eng died, just over two hours after his brother's death.[92] As of 2012, the Bunkers have the longest lifespan (62 years) of conjoined twins in history.[93] Eng was remembered as a caring supporter of his brother, especially during their final years, when Chang developed illnesses. After their death, their good friend Jesse Franklin Graves recalled, "[Eng's] kindness was received with the warmest appreciation by Chang, whose disposition was very different from the morose, ill nature so falsely ascribed to him [by the press]."[94]

Autopsy

Robert Bogdan

Freak Show (1990)[95]

The New York Herald ran a front-page story about the Bunker's deaths which attracted public demand for an autopsy and the attention of William Pancoast, who successfully petitioned for the opportunity to study the twins. It was rumored that Pancoast and other physicians had offered money to Chang and Eng's widows to inspect the twins, but more likely the doctors pressured the sisters' into giving up the bodies by framing it as their "duty to science and humanity". The bodies were preserved for two weeks by the cold weather, and then an express train delivered the bodies to the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, where the autopsy was performed and where preliminary findings were presented on February 18 while the autopsy was in progress.[96]

The twins' autopsy report said that Chang had most likely died of a cerebral blood clot; the cause of Eng's death was left unclear. Pancoast and colleague Harrison Allen attributed it to shock—that is, Eng "died of fright" upon seeing his dead brother—based on the fact that Eng's bladder had distended with urine and his right testicle had retracted. Alternate theories were suggested by people who worked on the autopsy, most prominently that Eng had died of blood loss as his circulatory system pumped blood through the connecting band into his dead brother's body and received none in return. "In the end," wrote academic Cynthia Wu in 2012, "that Eng died of fright prevails not only in the medical record but also in the popular-cultural imagination."[97]

Legacy

The Bunker brothers coined the term "Siamese twins", and their fame made it a synonym for conjoined twins in colloquial use, even referring those before the Bunkers' lifetime. The phrase "like the Siamese twins" (or variations) was used as early as October 1829 to describe other conjoined twins. Decades later use of the standalone "Siamese twins"—which modern researches see as outmoded, preferring "conjoined twins"—became widespread.[98] Thus Chang and Eng have often been retrospectively referred to as the "original Siamese twins".[2]

Before the Bunkers' bodies were returned to North Carolina for burial (in 1917 they were moved to the cemetery at White Plains Baptist Church outside Mount Airy), doctors took photographs of the connecting tissue and hired sculptor John Casani to make a plaster cast of the twins. The Bunkers' fused livers are preserved in fluid and displayed in a clear jar along with the death cast in Philadelphia's Mütter Museum as a permanent exhibition.[99] The Circus World Museum houses life-size figures of the twins.[76] The Southern Historical Collection of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill keeps the Bunkers' personal papers.[100]

In fiction

Many anonymous promotional pamphlets were printed depicting the Bunkers in artwork and literature, comprising early fiction pieces on the "Siamese twins"; the twins were used more metaphorically in later works.[101] Mentioned in his novels The Confidence-Man and Billy Budd, Herman Melville alludes to the Bunkers in Moby-Dick.[102] The anti-socialist political cartoonist Thomas Nast in 1874 drew "The American Twins"—a worker wears an apron ("Labor") next to a businessman with a sack of money ("Capital") joined at the chests with a band labeled "The Real Union".[103] Before the United States entered World War II, in his 1941 cartoon "The Great U.S. Sideshow" Dr. Seuss used a "Siamese Beard" to attach a man with an America First shirt to Nazi Germany.[104]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Mark Twain referenced conjoined twins in several ways such as by wearing a pink sash connecting him to another man onstage at a New Year's Eve party; in "Personal Habits of the Siamese Twins" (1869), republished as "The Siamese Twins" in his 1875 collection Sketches New and Old, Twain provides an account of the Bunkers' lives, including both true and outlandish anecdotes. The satirical work with Twain's typical deadpan humor jokes about, among other things, the twins' different attitudes and their romantic pursuit of the same woman.[105]

The musical Chang & Eng, directed by Ekachai Uekrongtham, has themes of open-mindedness and interdependence and opened in Singapore in 1997.[76] The debut novel of author Darin Strauss, Chang & Eng (2000), is a fictionalized account of the Bunker brothers' lives based on some historical context.[106] Chang narrates Mark Slouka's first novel God's Fool (2002), with a hindsight in which he knows the importance of future events.[107] The play I Dream of Chang and Eng by playwright Philip Kan Gotanda, a "reimagining" of the twins' lives which departs somewhat from truthfulness, was workshopped and performed at UC Berkeley in 2011.[108] Chang and Eng (played by Danial Son and Yusaku Komori) are featured in the musical biopic The Greatest Showman (2017) about the early years of the Barnum & Bailey Circus.[109]

See also

Notes and references

- Explanatory notes

- ↑ Their parents named them In and Chun (or Jun), which contrary to popular belief during their lifetime do not mean "left" and right", and they were known locally as the "Chinese twins". Western pronunciations made the English-language spellings "Chang" and "Eng". Huang 2018, pp. 27–28.

- ↑ The earliest report of their birth date is in the Boston Patriot and Mercantile Advertiser published August 17, 1829. Other reports give dates in late 1811 or early 1812. Records from Siamese royalty lead to the year 1812. An attempt to locate a specific date of birth is likely futile, as no birth records of the twins exist. Orser 2014, pp. 11, 208. Whatever the real date may be, May 11, 1811, is the generally accepted one Orser 2014, p. 194.

- ↑ There are several narratives relating to Chang and Eng's siblings. Their mother had several other children, though stories attributing to her multiple sets of twins or triplets are probably misguided Orser 2014, p. 11.

- ↑ In his November 1829 account of the discovery, John Collins Warren writes, "They were naked from the hips upwards, were very thin in their persons, and it being dusk, he mistook them for some strange animal". Orser 2014, p. 13.

- ↑ Their mother said that she had a "strong desire to see them again". Despite the missionaries' claim that they would return, evidence does not suggest that their mother was reached again. Orser 2014, p. 108.

- ↑ In October 1839 Harris wed Frances "Fannie" Baugus, daughter of Robert Baugus, who had helped the twins with living arrangements when they first arrived in Wilkes. In November 1840, Fanny's older brother Samuel married Letha Yates, daughter of David and Nancy Yates and older sister to the twins' future wives. Thus Chang and Eng would become related to Harris by marriage Orser 2014, pp. 85–86, 88.

- ↑ According to Orser, "The twins were applying in a county that had very few immigrants and no other Asians, in a region whose color line was drawn decisively between white and black, in a court where they had been neighbors with the man administering the oaths [Gwyn]." Orser 2014, p. 82.

- ↑ On race, Wu concludes Chapter 1, "Labor and Ownership in the American South" thusly (paraphrased): The Bunkers were Asian Americans; however, they could circumvent many de jure and de facto restrictions on others like them. They were nonwhite and interacted with other nonwhites mostly as slaveholders. "These tensions on interconnectedness and partition, on multiple levels, constitute the numerous contradictions the Bunkers present to the complicated landscape of American culture." Wu 2012, pp. 34–35.

- ↑ Orser notes that the narrative about protesters smashing the twins' windows because of their marriage was most likely introduced in Kay Hunter's 1964 popular biography Duet for a Lifetime; she "did not disclose her sources for this specific detail". Orser 2014, p. 95.

- ↑ For instance, the Greensborough Patriot wrote: "In driving a horse or chastising their negroes, both of them [the Bunkers] use the lash without mercy. A gentleman who purchased a black man, a short time ago, from them, informed the writer he was 'the worst whipped negro' he ever saw." Chang and Eng replied quickly: "That portion of said piece relating to the inhuman manner in which we had chastized a negro man which we afterwards sold is a sheer fabrication and infamous falsehood." Orser 2014, p. 127.

- ↑ For instance, the St. Louis Republican fictitiously (it included the caveat the it "does not vouch for its truth") wrote that disagreements between the Bunker brothers had escalated to their killing each other's children. Orser 2014, p. 149.

- ↑ An 1829 description reads, "Deviations from the usual forms of nature are almost always universally offensive; but, in this case, neither the personal appearance of the boys, nor the explanation of the phenomenon by which they are united, is calculated to raise an unpleasant emotion." Quigley 2012, p. 23.

- References

- ↑ "The Grave of Chang and Eng Bunker". Atlas Obscura. Archived from the original on July 19, 2018. Retrieved July 18, 2018.

- 1 2 Quigley 2012, p. 22.

- ↑ Dreger 2005, p. 19; Wu 2012, p. 3 (birth).

- ↑ Orser 2014, p. 11.

- ↑ Quigley 2012, pp. 22, 39.

- ↑ Orser 2014, p. 11; Huang 2018, p. 26 (names), 36 (help).

- ↑ Orser 2014, p. 15.

- ↑ Orser 2014, p. 108 (religion); Dreger 2005, p. 19 (activity).

- ↑ Dreger 2005, p. 19.

- ↑ Orser 2014, pp. 9, 12; Wu 2012, p. 4.

- ↑ Orser 2014, pp. 13–14, 246; Spencer 2003, p. 2: new creature.

- ↑ Orser 2014, p. 13.

- ↑ Orser 2014, p. 9 (travel), 48 (contract): Hunter and Coffin said the contract for $3,000. Chang and Eng said it was $500.

- ↑ Orser 2014, pp. 37, 39–40, 48.

- ↑ Orser 2014, p. 108.

- ↑ Orser 2014, p. 42.

- ↑ Orser 2014, p. 9.

- ↑ Wu 2012, p. 1.

- ↑ Orser 2014, pp. 20–21, 23–25.

- ↑ Orser 2014, pp. 41–42.

- ↑ Orser 2014, pp. 38 (travel custom); Bogdan 1990, p. 12, 30–31 ("freak show").

- ↑ Orser 2014, pp. 14, 42, 61, 73; Bogdan 1990, p. 115.

- ↑ Orser 2014, pp. 45–46: The bond was $200, equivalent to $4,596 in 2017.

- ↑ Orser 2014, pp. 46–47, 50–51, 53.

- ↑ Orser 2014, pp. 54–55.

- ↑ Orser 2014, pp. 61–62: The bond was $350, equivalent to $8,043 in 2017.

- ↑ Orser 2014, pp. 63–64.

- ↑ Orser 2014, pp. 64, 66.

- ↑ Orser 2014, pp. 55, 64–67.

- ↑ Orser 2014, p. 68.

- ↑ Orser 2014, pp. 68–69.

- ↑ Wu 2012, p. 4.

- ↑ Orser 2014, pp. 61, 70–71, 73.

- ↑ Orser 2014, p. 73–74.

- ↑ Orser 2014, p. 78.

- ↑ Orser 2014, pp. 76, 81–83.

- ↑ Orser 2014, pp. 79–81.

- ↑ Orser 2014, pp. 81–82.

- 1 2 3 Orser 2014, p. 109.

- ↑ Orser 2014, p. 84; Huang 2018, p. 239 (Gates).

- ↑ Orser 2014, p. 84.

- ↑ Orser 2014, pp. 85, 221.

- ↑ Orser 2014, p. 105.

- ↑ Orser 2014, pp. 89–93.

- ↑ Orser 2014, pp. 94–101; Wu 2012, p. 4.

- ↑ Bogdan 1990, p. 204.

- 1 2 Orser 2014, pp. 105–106.

- ↑ Orser 2014, p. 112.

- ↑ Orser 2014, p. 132; Wu 2012, p. 35.

- ↑ Orser 2014, pp. 110–112.

- ↑ Orser 2014, p. 110.

- 1 2 Wu 2012, p. 40.

- ↑ Orser 2014, p. 126.

- ↑ Orser 2014, p. 127.

- ↑ Orser 2014, pp. 113–114.

- 1 2 Orser 2014, p. 137.

- ↑ Orser 2014, p. 140; Bogdan 1990, pp. 115–116.

- ↑ Orser 2014, p. 118.

- ↑ Orser 2014, p. 141; Wu 2012, p. 16.

- ↑ Wu 2012, pp. 1, 16–17.

- ↑ Orser 2014, p. 141.

- ↑ Orser 2014, pp. 144–145.

- 1 2 Orser 2014, pp. 145–146.

- ↑ Orser 2014, pp. 154–156.

- ↑ Orser 2014, pp. 147–148.

- ↑ Orser 2014, pp. 149–150.

- ↑ Orser 2014, p. 148.

- ↑ Orser 2014, p. 151.

- ↑ Orser 2014, p. 150; Wu 2012, p. 179, note 37.

- 1 2 Orser 2014, p. 161.

- ↑ Orser 2014, pp. 158–161, 167 (for parenthetical); Wu 2012, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Orser 2014, pp. 162–165.

- ↑ Orser 2014, p. 171.

- 1 2 Orser 2014, p. 88.

- 1 2 Orser 2014, pp. 112–113, 227.

- 1 2 3 4 Quigley 2012, p. 39.

- ↑ Orser 2014, pp. 135–136.

- ↑ Orser 2014, p. 133.

- ↑ Orser 2014, p. 138.

- ↑ Newman 2006, p. 1.

- ↑ Wu 2012, p. 146; Orser 2014.

- ↑ Patterson, Michael Robert (July 9, 2002). "Major General Caleb Vance Haynes". arlingtoncemetary.net. Archived from the original on July 19, 2018. Retrieved July 18, 2018.

- ↑ Wu 2012, p. 151.

- ↑ Medetti, Stefania (November 1, 2013). "Caroline Shaw, the Pulitzer girl". Vogue Italia. Archived from the original on July 19, 2018. Retrieved July 18, 2018.

- ↑ Klein, Maury (2006) [1989]. Union Pacific: Volume II, 1894-1969. Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press. p. 437. ISBN 978-0-8166-4460-5.

- 1 2 Newman 2006, p. 2.

- ↑ Dreger 2005, p. 19; Wu 2012, p. 55 ("xiphopagic" is a synonym).

- ↑ Quigley 2012, p. 23.

- ↑ Quigley 2012, p. 5; Spencer 2003, p. 58; Wu 2012, p. 53.

- ↑ Wu 2012, pp. 40 (college), 53–54.

- ↑ Orser 2014, pp. 171–174.

- ↑ Wu 2012, p. 40; Orser 2014, p. 175.

- ↑ Wu 2012, p. 5.

- ↑ Dreger 2005, p. 22.

- ↑ Bogdan 1990, p. 296, note 1.

- ↑ Wu 2012, pp. 40–42; Orser 2014, p. 185–186.

- ↑ Wu 2012, pp. 54–56.

- ↑ Dreger 2005, p. 22; Orser 2014, p. 22; Wu 2012, p. 1.

- ↑ Wu 2012, p. 58; Quigley 2012, p. 39; Orser 2014, p. 193 (for parenthetical).

- ↑ Quigley 2012, p. 40.

- ↑ Wu 2012, p. 85.

- ↑ Wu 2012, pp. 85–86.

- ↑ Wu 2012, pp. 93–94.

- ↑ Wu 2012, pp. 96–97.

- ↑ Wu 2012, pp. 86–87.

- ↑ Santella, Andrew (June 4, 2000). "The Siamese Twins". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 8, 2018. Retrieved July 18, 2018.

- ↑ Hall, Emily (May 26, 2002). "Books in Brief: Fiction and Poetry (God's Fool)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 19, 2018. Retrieved July 18, 2018.

- ↑ Jones, Chad (March 3, 2011). "Philip Kan Gotanda's 'I Dream of Chang and Eng'". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on July 3, 2018. Retrieved July 18, 2018.

- ↑ Vognar, Chris (December 15, 2017). "'Greatest Showman' P.T. Barnum was also a master racial mythmaker". The Dallas Morning News. Archived from the original on July 19, 2018. Retrieved July 18, 2018.

- Bibliography

- Bogdan, Robert (1990), Freak Show: Presenting Human Oddities for Amusement and Profit, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-06312-6

- Dreger, Alice Domurat (2005), One of Us: Conjoined Twins and the Future of Normal, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-01825-9

- Huang, Yunte (2018), Inseparable: The Original Siamese Twins and their Rendezvous with American History, W. W. Norton & Company, ISBN 978-0-87140-447-3

- Newman, Cathy (June 2006). "Together Forever". National Geographic. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on March 6, 2012.

- Orser, Joseph Andrew (2014), The Lives of Chang & Eng: Siam's Twins in Nineteenth-Century America, University of North Carolina Press, ISBN 978-1-4696-1830-2

- Quigley, Christine (2012), "Bunker, Chang and Eng", Conjoined Twins: An Historical, Biological and Ethical Issues Encyclopedia, McFarland & Company, pp. 22–40, ISBN 978-1-4766-0323-0

- Spencer, Rowena (2003), Conjoined Twins: Developmental Malformations and Clinical Implications, Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 978-0-8018-7070-5

- Wu, Cynthia (2012), Chang and Eng Reconnected, Temple University Press, ISBN 978-1-4399-0869-3

Further reading

- Dreger, Alice Domurat (March 1998). "The limits of individuality: Ritual and sacrifice in the lives and medical treatment of conjoined twins". Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Biological and Biomedical Sciences. 29 (1): 1–29. doi:10.1016/S1369-8486(98)00002-8.

- Martin, Holly E. (December 2011). "Chang and Eng Bunker, 'The Original Siamese Twins': Living, Dying, and Continuing under the Spectator's Gaze". The Journal of American Culture. 34 (4): 372–390. doi:10.1111/j.1542-734X.2011.00787.x.

- Miller, Candice (June 1, 2018). "Who Were the Original Siamese Twins?". The New York Times Sunday Book Review.

- Mitchell, Sarah (December 2003). "Exhibiting monstrosity: Chang and Eng, the 'original' Siamese twins". Endeavour. 27 (4): 150–154. doi:10.1016/j.endeavour.2003.10.001.

- Schuknecht, Harold F. (December 1979). "The Siamese Twins, Eng and Chang: Their Lives and Their Hearing Losses". Archives of Otolaryngology. 105 (12): 737–740. doi:10.1001/archotol.1979.00790240051012.

External links

- The Chang and Eng Bunker Project at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

- Bunkers Digital Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (View digitized collection)

- Chang and Eng Bunker Papers at the Southern Historical Collection

- Chang and Eng Exhibit (photographs with commentary) at the City University of New York