Robert Hunter (trader)

Robert Hunter was a British trader and diplomat in Siam during the reign of King Rama III. Hunter settled in Bangkok in 1824 and served as an intermediary between Westerners and the court until his departure from the country in 1844 over a trade dispute with the king.

Settlement in Siam

Hunter began his commercial career trading in India before moving to Singapore. While Hunter was living in Singapore, the East India Company sent its first diplomatic mission to the Kingdom of Siam, but failed to secure a treaty with King Rama II for trading rights. In July 1824, Rama III succeeded to the throne in Bangkok, and Hunter arrived in August, bearing gifts for the new king. After speaking with the Phra Klang (Minister of the Treasury), Hunter was granted the right to trade with foreigners on behalf of the king and was permitted to live in Bangkok. The king ordered a three-storey construction erected for Hunter's business and residence.

Role in diplomacy

Westerners came to refer to the building as the British factory;[1] in absence of a British embassy or formal Anglo-Siamese diplomatic relations, Hunter personally managed the exchange of goods and visitors between Singapore – the nearest British entrepôt – and Bangkok.

Hunter's privileged position at court enabled him to guide diplomatic and Christian missions entering the country. Most notably, he aided Henry Burney's successful treaty mission in 1826. The governor of Singapore later praised Hunter for a history of "infinite service in our negotiation with [Rama III]".[2] Hunter was also lauded in Siam, receiving the fourth-highest title in the kingdom, Luang Awutwiset, in 1831.[3] In 1842 he helped negotiate for the restoration of the Sultan of Kedah after 20 years of Siamese occupation.[4]

"Discovery" of Siamese twins

Hunter is credited with bringing the original Siamese twins to global attention. In 1824, he was sailing up the Menam River at dusk when he saw a "strange animal" – in actuality the shirtless twins bathing.[5] Recognizing the potential profit in exhibiting them publicly, Hunter sought permission from the king to bring them to the West,[6] Five years later, he had secured permission from the king to do so. (He later claimed that Rama had originally ordered for the brothers to be executed and forbade him to transport them out of the country.) Hunter's partner in this business venture was American sea captain Abel Coffin. Coffin and Hunter sailed to Boston with the twins in the summer of 1829.[7] They signed a contract with the brothers for a five-year tour, and the value of the contract is disputed. Hunter and Coffin said it was for $3,000, but Chang and Eng said it was for $500.[8]

Origins of trading conflict with Rama III

Hunter partnered in trade with another British merchant, James Hayes. The Burney Treaty granted more trading privileges for all British merchants in Singapore, but Hunter & Hayes dominated the market.[9]

As trade increased through the 1830s, Siam’s nobles began to deal with foreign merchants more independently of Hunter. He decided to compensate for his falling profits by trading in opium – which was strictly forbidden in the kingdom at the time.[10] The king lacked definitive proof of Hunter's opium smuggling, however, and Siam did not have the naval means to disrupt shipments at sea. Goods laid in port, however, could be easily seized.[11]

In 1839, Hunter & Hayes complained of suffering great losses over the unexpected monopolization of teak[12] and then even greater loss at the monopolization of sugar in 1842.[13] Whereas he had once been partners with the king's court in trade, he had grown to be a rival.[14]

Express incident

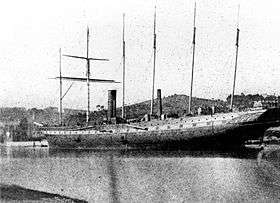

The climax of the conflict between Hunter and Rama III was over the sale of a steamship.

Apprehensive of British intentions in the region after the First Opium War, the king had ordered from Hunter & Hayes a large supply of guns and a steamship to use in case British gunships attacked Siam. The hostilities in China ended with the Treaty of Nanking in 1842, and the British did not proceed to attack Siam. Therefore, the king no longer wanted a steamship by the time Express arrived in Bangkok on 11 January 1844.

The sale of the ship was fraught with disagreement. It is unclear whether the king refused to pay the previously agreed price, or if Hunter attempted to extort from him quadruple the value of the vessel;[15] but tensions in the negotiations reached a boiling point when Hunter threatened to sell Express to Siam’s enemy, the Vietnamese in nearby Cochinchina.[16] The king was outraged by the threat and ordered Hunter to leave Siam immediately. On 24 February, Hunter departed Bangkok on Express, bound for Singapore.[17]

.jpg)

Upon landing in Singapore, Hunter lodged a complaint with the governor. Unsatisfied with his response, Hunter steamed Express to Calcutta, the headquarters of the East India Company, to petition for redress of his grievances with the king. He claimed that Rama III had violated articles of the Burney Treaty of 1826, and he recommended the establishment of a British consul in Bangkok, appearance of gunships in the area and a renegotiation of the import duty. The Governor-General of India took no action, however, agreeing with the judgments of his subordinates that any violations on the king's part owed to personal dispute with Hunter and were not instances of systematic breach.[18] (The later Bowring Treaty of 1855 significantly liberalized trade between the British and Siam, notably allowing for the duty-free importation of opium.)

Hunter eventually made good on his threat and sold Express to the Vietnamese for a price of 53,000 Spanish dollars.

Christopher Harvey, an assistant of Hunter & Hayes, continued the business in Bangkok after Hunter’s departure in February.[19] Hunter returned to Bangkok only months later to collect his outstanding debts. (The king neither barred him from entering the country nor helped him to collect.) He dissolved his enterprise and departed Siam on 29 December 1844.[20]

Hunter returned to his native Scotland and died at his residence in Lilybank, Glasgow on 7 September 1847.[21]

Notes

- ↑ Moore, "Early British Merchant", pp. 21–23

- ↑ W.J. Butterworth to W. Edwards, 13 February 1845, in Burney Papers, Vol. 4, Pt. 2, p. 161

- ↑ Farrington, Early Missionaries, p. 159 n. 6

- ↑ Singhs, "Opening of Siam", p. 782

- ↑ In his November 1829 account of the discovery, John Collins Warren wrote: "They were naked from the hips upwards, were very thin in their persons, and it being dusk, he mistook them for some strange animal". Orser 2014, p. 13.

- ↑ Orser, Lives of Chang & Eng, pp. 13–14

- ↑ Orser, Lives of Chang & Eng, p. 9

- ↑ Orser, Lives of Chang & Eng, p. 48

- ↑ SarDesai, British Trade, p. 80

- ↑ Vella, Siam Under Rama III, pp. 128–9

- ↑ SarDesai, British Trade, p. 81

- ↑ Christopher Harvey to Lord Ellenborough, 28 May 1843, in Burney Papers, Vol. 4, Pt. 2, p. 81–3

- ↑ Robert Hunter to Lord Ellenborough, 24 April 1844, in Burney Papers, Vol. 4, Pt. 2, p. 130–1

- ↑ G. Broadfoot to F. Currie Esq., 2 July 1844, in Burney Papers, Vol. 4, Pt. 2, p. 141

- ↑ SarDesai, British Trade, p. 85 n. 59

- ↑ W.J. Butterworth to W. Edwards Esq., 13 February 1845, in Burney Papers, Vol. 4, Pt. 2, p. 165

- ↑ Bradley, Journal of Bradley, p. 92

- ↑ Singhs, "Opening of Siam", pp. 783–4

- ↑ Wilson, "State and Society, Part 1", p. 188

- ↑ Singhs, "Opening of Siam", p. 784

- ↑ Singapore Free Press, 16 November 1848

References

- The Burney Papers Vol. 4; Pt. 1 to 2. Bangkok: Vajiranana National Library. 1913. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- Bradley, Dan Beach (1936). Feltus, George Haws, ed. Abstract of the journal of Rev. Dan Beach Bradley, M.D., medical missionary in Siam, 1835-1873. Cleveland, OH: Pilgrim Church.

- Farrington, Anthony, ed. (2001). Early Missionaries in Bangkok: The Journals of Tomlin, Gutzlaff and Abeel 1828–1832. Bangkok: White Lotus Press. ISBN 9789747534832.

- Moore, R. Adey (1915). "An Early British Merchant in Bangkok" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. 11 (2): 21–39.

- Orser, Joseph Andrew (2014). The Lives of Chang & Eng: Siam's Twins in Nineteenth-Century America. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-4696-1830-2.

- SarDesai, D.R. (1977). British Trade and Expansion in Southeast Asia: 1830–1914. New Delhi: Allied Publishers.

- "Untitled". The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser. Singapore. 16 November 1848. p. 3. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- Singh, S.B.; Singh, S.P. (1997). "The Opening of Siam (Thailand)". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 58: 779–786. JSTOR 44144022.

- Vella, Walter F. (1957). Siam Under Rama III, 1824–51. Locust Valley, NY: J.J. Augustin.

- Wilson, Constance M. (1970). State and Society in the Reign of Mongkut, 1851–1868: Thailand on the Eve of Modernization, parts 1–2 (PhD). Cornell University.