Chalcedony

| Chalcedony | |

|---|---|

| |

| General | |

| Category | Oxide minerals, quartz group |

| Formula (repeating unit) |

Silica (silicon dioxide, SiO 2) |

| Crystal system | Trigonal or monoclinic |

| Identification | |

| Formula mass | 60 g/mol |

| Color | Various |

| Cleavage | Absent |

| Fracture | Uneven, splintery, conchoidal |

| Mohs scale hardness | 6 - 7 |

| Luster | Waxy, vitreous, dull, greasy, silky |

| Streak | White |

| Diaphaneity | Translucent |

| Specific gravity | 2.59 - 2.61 |

| References | [1] |

Chalcedony ( /kælˈsɛdəni/) is a cryptocrystalline form of silica, composed of very fine intergrowths of quartz and moganite.[2] These are both silica minerals, but they differ in that quartz has a trigonal crystal structure, while moganite is monoclinic. Chalcedony's standard chemical structure (based on the chemical structure of quartz) is SiO2 (silicon dioxide).

Chalcedony has a waxy luster, and may be semitransparent or translucent. It can assume a wide range of colors, but those most commonly seen are white to gray, grayish-blue or a shade of brown ranging from pale to nearly black. The color of chalcedony sold commercially is often enhanced by dyeing or heating.[3]

The name chalcedony comes from the Latin chalcedonius (alternatively spelled calchedonius). The name appears in Pliny the Elder's Naturalis Historia as a term for a translucid kind of Jaspis.[4] The name is probably derived from the town Chalcedon in Asia Minor.[5] The Greek word khalkedon (χαλκηδών) also appears in the Book of Revelation (Apc 21,19). It is a hapax legomenon found nowhere else, so it is hard to tell whether the precious gem mentioned in the Bible is the same mineral known by this name today.[6]

Varieties

Chalcedony occurs in a wide range of varieties. Many semi-precious gemstones are in fact forms of chalcedony. The more notable varieties of chalcedony are as follows:

Agate

Agate is a variety of chalcedony characterized by either transparency or color patterns, such as multi-colored curved or angular banding. Opaque varieties are sometimes referred to as jasper.[3] Fire agate shows iridescent phenomena on a brown background; iris agate shows exceptional iridescence when light (especially pinpointed light) is shone through the stone. Landscape agate is chalcedony with a number of different mineral impurities making the stone resemble landscapes.[7]

Aventurine

Aventurine is a form of quartz, characterised by its translucency and the presence of platy mineral inclusions that give a shimmering or glistening effect termed aventurescence. Chrome-bearing fuchsite (a variety of muscovite mica) is the classic inclusion, and gives a silvery green or blue sheen. Oranges and browns are attributed to hematite or goethite.

Carnelian

.jpg)

Carnelian (also spelled cornelian) is a clear-to-translucent reddish-brown variety of chalcedony. Its hue may vary from a pale orange, to an intense almost-black coloration. Similar to carnelian is sard, which is brown rather than red.

Chrysoprase

Chrysoprase (also spelled chrysophrase) is a green variety of chalcedony, which has been colored by nickel oxide. (The darker varieties of chrysoprase are also referred to as prase. However, the term prase is also used to describe green quartz, and to a certain extent is a color-descriptor, rather than a rigorously defined mineral variety.)

Blue-colored chalcedony is sometimes referred to as "blue chrysoprase" if the color is sufficiently rich, though it derives its color from the presence of copper and is largely unrelated to nickel-bearing chrysoprase.

Heliotrope

Heliotrope is a green variety of chalcedony, containing red inclusions of iron oxide that resemble drops of blood, giving heliotrope its alternative name of bloodstone. In a similar variety, the spots are yellow instead, known as plasma.

Moss agate

Moss agate contains green filament-like inclusions, giving it the superficial appearance of moss or blue cheese. There is also tree agate which is similar to moss agate except it is solid white with green filaments whereas moss agate usually has a transparent background, so the "moss" appears in 3D. It is not a true form of agate, as it lacks agate's defining feature of concentric banding.

Mtorolite

Mtorolite is a green variety of chalcedony, which has been colored by chromium. Also known as chrome chalcedony, it is principally found in Zimbabwe.

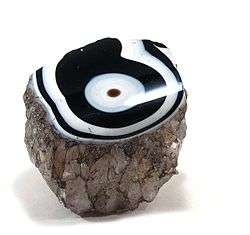

Onyx

Onyx is a variant of agate with black and white banding. Similarly, agate with brown, orange, red and white banding is known as sardonyx.

Aquaprase

Aquaprase is a blue-green variety of Chalcedony, originally confused for a chrysoprase. It is found in an undisclosed region of Africa.

History

As early as the Bronze Age chalcedony was in use in the Mediterranean region; for example, on Minoan Crete at the Palace of Knossos, chalcedony seals have been recovered dating to circa 1800 BC.[8] People living along the Central Asian trade routes used various forms of chalcedony, including carnelian, to carve intaglios, ring bezels (the upper faceted portion of a gem projecting from the ring setting), and beads that show strong Greco-Roman influence.

Fine examples of first century objects made from chalcedony, possibly Kushan, were found in recent years at Tillya-tepe in north-western Afghanistan.[9] Hot wax would not stick to it so it was often used to make seal impressions. The term chalcedony is derived from the name of the ancient Greek town Chalkedon in Asia Minor, in modern English usually spelled Chalcedon, today the Kadıköy district of Istanbul.

According to tradition, at least three varieties of chalcedony were used in the Jewish High Priest's Breastplate. (Jewish tradition states that Moses' brother Aaron wore the Breastplate, with inscribed gems representing the twelve tribes of Israel). The Breastplate supposedly included jasper, chrysoprase and sardonyx, and there is some debate as to whether other agates were also used.

In the 19th century, Idar-Oberstein, Germany, became the world's largest chalcedony processing center, working mostly on agates. Most of these agates were from Latin America, in particular Brazil. Originally the agate carving industry around Idar and Oberstein was driven by local deposits that were mined in the 15th century.[10] Several factors contributed to the re-emergence of Idar-Oberstein as agate center of the world: ships brought agate nodules back as ballast, thus providing extremely cheap transport. In addition, cheap labor and a superior knowledge of chemistry allowed them to dye the agates in any color with processes that were kept secret. Each mill in Idar-Oberstein had four or five grindstones. These were of red sandstone, obtained from Zweibrücken; and two men ordinarily worked together at the same stone.[10]

Geochemistry

Structure

Chalcedony was once thought to be a fibrous variety of cryptocrystalline quartz.[11] More recently however, it has been shown to also contain a monoclinic polymorph of quartz, known as moganite.[2] The fraction, by mass, of moganite within a typical chalcedony sample may vary from less than 5% to over 20%.[12] The existence of moganite was once regarded as dubious, but it is now officially recognised by the International Mineralogical Association.[13][14]

Solubility

Chalcedony is more soluble than quartz under low-temperature conditions, despite the two minerals being chemically identical. This is thought to be because chalcedony is extremely finely grained (cryptocrystalline), and so has a very high surface area to volume ratio. It has also been suggested that the higher solubility is due to the moganite component.[12]

Solubility of quartz and chalcedony in pure water

This table gives equilibrium concentrations of total dissolved silicon as calculated by PHREEQC (PH REdox EQuilibrium (in C language, USGS)) using the llnl.dat database.

| Temperature | Quartz solubility (mg/L) | Chalcedony solubility (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.01 °C | 0.68 | 1.34 |

| 25.0 °C | 2.64 | 4.92 |

| 50.0 °C | 6.95 | 12.35 |

| 75.0 °C | 14.21 | 24.23 |

| 100.0 °C | 24.59 | 40.44 |

See also

References

- ↑ Duda, Rudolf; Rejl, Lubos (1990). Minerals of the World. Arch Cape Press.

- 1 2 Heaney, Peter J. (1994). "Structure and Chemistry of the low-pressure silica polymorphs". In Heaney, P. J.; Prewitt, C. T.; Gibbs, G. V. Silica: Physical Behavior, geochemistry and materials applications. Reviews in Mineralogy. 29. pp. 1–40.

- 1 2 "Chalcedony Gemological Information". International Gem Society (IGS). Archived from the original on 7 February 2015. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ↑ Pliny the Elder. "chapter 7". Naturalis Historiae. Book 37. p. 115.

- ↑ Zwierlein-Diehl, Erika (2007). Antike Gemmen und ihr Nachleben. Berlin: Verlag Walter de Gruyter. S. 307. According to the OED a connection with the town of Chalcedon is "very doubtful":Harper, Douglas. "Chalcedony". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ↑ James Orr, ed. (1915). "Chalkēdōn". The International Standard Bible Encyclopaedia. The Howard-Severance company. p. 2859.

- ↑ CIBJO member laboratories (May 2009). "Retailers' Reference Guide: Diamonds, Cemstones, Pearls and Precious Metals". Bern, Switzerland: CIBJO (The World Jewellery Federation, international federation of all national trade organizations and gemological laboratories).

- ↑ Hogan, C. Michael (2007). "Knossos fieldnotes". Modern Antiquarian. Archived from the original on 2016-04-09.

- ↑ Section 12 of the translation of Weilue - a 3rd-century Chinese text by John Hill under "carnelian" and note 12.12 (17)A. Also see Afghanistan's exhibition:Intaglio with depiction of a griffin, Chalcedony, 4th century BC, Afghanistan Archived February 25, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Streeter, Edwin (1898). Precious Stones and Gems. p. 237.

- ↑ "Chalcedony mineral information and data". www.mindat.org. Archived from the original on 2006-08-21.

- 1 2 Heaney, Peter J.; Post, Jeffrey E. (24 January 1992). "The Widespread Distribution of a Novel Silica Polymorph in Microcrystalline Quartz Varieties". Science. New Series. 255 (5043): 441–443. doi:10.1126/science.255.5043.4. JSTOR 2876012. PMID 17842895.

- ↑ Origlieri, Marcus (January 1994). "Moganite: a New Mineral -- Not!". Lithosphere. Archived from the original on March 9, 2008.

- ↑ Nickel, Ernest H.; Nichols, Monte C. (16 May 2008). "IMA/CNMNC List of Mineral Names" (PDF). Materials Data. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-05-30. Retrieved 2008-06-29. >

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Chalcedony. |

- Mindat: mineralogical data Chalcedony

- USGS: US Chalcedony locations