Hapax legomenon

In corpus linguistics, a hapax legomenon (/ˈhæpəks

The related terms dis legomenon, tris legomenon, and tetrakis legomenon respectively (/ˈdɪs/, /ˈtrɪs/, /ˈtɛtrəkɪs/) refer to double, triple, or quadruple occurrences, but are far less commonly used.

Hapax legomena are quite common, as predicted by Zipf's law,[4] which states that the frequency of any word in a corpus is inversely proportional to its rank in the frequency table. For large corpora, about 40% to 60% of the words are hapax legomena, and another 10% to 15% are dis legomena.[5] Thus, in the Brown Corpus of American English, about half of the 50,000 distinct words are hapax legomena within that corpus.[6]

Hapax legomenon refers to a word's appearance in a body of text, not to either its origin or its prevalence in speech. It thus differs from a nonce word, which may never be recorded, may find currency and may be widely recorded, or may appear several times in the work which coins it, and so on.

Significance

Hapax legomena in ancient texts are usually difficult to decipher, since it is easier to infer meaning from multiple contexts than from just one. For example, many of the remaining undeciphered Mayan glyphs are hapax legomena, and Biblical (particularly Hebrew; see § Hebrew examples) hapax legomena sometimes pose problems in translation. Hapax legomena also pose challenges in natural language processing.[7]

Some scholars consider Hapax legomena useful in determining the authorship of written works. P. N. Harrison, in The Problem of the Pastoral Epistles (1921)[8] made hapax legomena popular among Bible scholars, when he argued that there are considerably more of them in the three Pastoral Epistles than in other Pauline Epistles. He argued that the number of hapax legomena in a putative author's corpus indicates his or her vocabulary and is characteristic of the author as an individual.

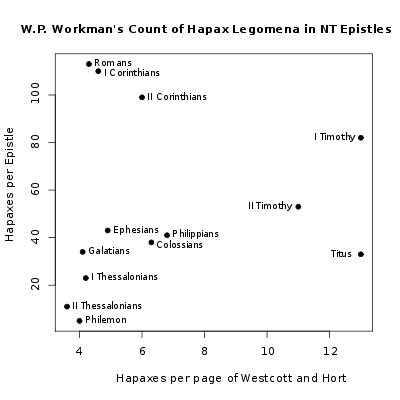

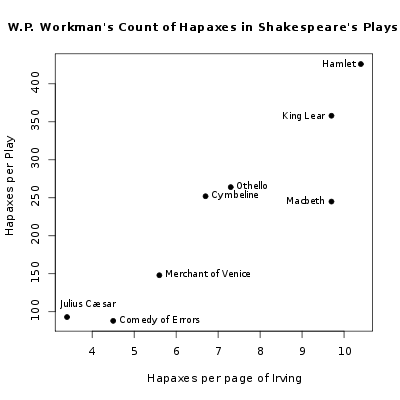

Harrison's theory has faded in significance due to a number of problems raised by other scholars. For example, in 1896, W. P. Workman found the following numbers of hapax legomena in each Pauline Epistle: Rom. 113, I Cor. 110, II Cor. 99, Gal. 34, Eph. 43 Phil. 41, Col. 38, I Thess. 23, II Thess. 11, Philem. 5, I Tim. 82, II Tim. 53, Titus 33. At first glance, the last three totals (for the Pastoral Epistles) are not out of line with the others.[9] To take account of the varying length of the epistles, Workman also calculated the average number of hapax legomena per page of the Greek text, which ranged from 3.6 to 13, as summarized in the diagram on the right.[9] Although the Pastoral Epistles have more hapax legomena per page, Workman found the differences to be moderate in comparison to the variation among other Epistles. This was reinforced when Workman looked at several plays by Shakespeare, which showed similar variations (from 3.4 to 10.4 per page of Irving's one-volume edition), as summarized in the second diagram on the right.[9]

Apart from author identity, there are several other factors that can explain the number of hapax legomena in a work:[10]

- text length: this directly affects the expected number and percentage of hapax legomena; the brevity of the Pastoral Epistles also makes any statistical analysis problematic.

- text topic: if the author writes on different subjects, of course many subject-specific words will occur only in limited contexts.

- text audience: if the author is writing to a peer rather than a student, or their spouse rather than their employer, again quite different vocabulary will appear.

- time: over the course of years, both the language and an author's knowledge and use of language will change.

In the particular case of the Pastoral Epistles, all of these variables are quite different from those in the rest of the Pauline corpus, and hapax legomena are no longer widely accepted as strong indicators of authorship (although the authorship of the Pastorals is subject to debate on other grounds).[11]

There are also subjective questions over whether two forms amount to "the same word": dog vs. dogs, clue vs. clueless, sign vs. signature; many other gray cases also arise. The Jewish Encyclopedia points out that, although there are 1,500 hapaxes in the Hebrew Bible, only about 400 are not obviously related to other attested word forms.[12]

It would not be especially difficult for a forger to construct a work with any percentage of hapax legomena desired. However, it seems unlikely that forgers much before the 20th century would have conceived such a ploy, much less thought it worth the effort.

A final difficulty with the use of hapax legomena for authorship determination is that there is considerable variation among works known to be by a single author, and disparate authors often show similar values. In other words, hapax legomena are not a reliable indicator. Authorship studies now usually use a wide range of measures to look for patterns rather than rely upon single measurements.

Computer science

In the fields of computational linguistics and natural language processing (NLP), esp. corpus linguistics and machine-learned NLP, it is common to disregard hapax legomena (and sometimes other infrequent words), as they are likely to have little value for computational techniques. This disregard has the added benefit of significantly reducing the memory use of an application, since, by Zipf's law, many words are hapax legomena.[13]

Examples

The following are some examples of hapax legomena in languages or corpora.

Arabic examples

- The proper nouns Iram (Q 89:7, Iram of the Pillars), Bābil (Q 2:102, Babylon), Bakka(t) (Q 3:96, Bakkah), Jibt (Q 4:51), Ramaḍān (Q 2:185, Ramadan), ar-Rūm (Q 30:2, Byzantine Empire), Tasnīm (Q 83:27), Qurayš (Q 106:1, Quraysh), Majūs (Q 22:17, Magi), Mārūt (Q 2:102, Harut and Marut), Makka(t) (Q 48:24, Mecca), Nasr (Q 71:23), (Ḏū) an-Nūn (Q 21:87) and Hārūt (Q 2:102, Harut and Marut) occur only once in the Qurʾān.[14]

- zanjabīl (زَنْجَبِيل – ginger) is a Qurʾānic hapax (Q 76:17).

- The epitheton ornans aṣ-ṣamad (الصَّمَد – the One besought) is a Qurʾānic hapax (Q 112:2).

English examples

_-_page_47_-_honorificabilitudinitatibus.jpg)

- Flother, as a synonym for snowflake, is a hapax legomenon of written English found in a manuscript entitled The XI Pains of Hell (circa 1275).[15][16]

- Hebenon, a poison referred to in Shakespeare's 'Hamlet' only once.

- Honorificabilitudinitatibus is a hapax legomenon of Shakespeare's works.

- Manticratic, meaning "of the rule by the prophet's family or clan" was apparently invented by T. E. Lawrence and appears once in "Seven Pillars of Wisdom."

- Nortelrye, a word for "education", occurs only once in Chaucer.

- Sassigassity, perhaps with the meaning of "audacity", occurs only once in Dickens's short story "A Christmas Tree".

- Satyr occurs only once in Shakespeare's writings.[17]

- Slæpwerigne "sleep-weary" occurs exactly once in the old-English corpus, the Exeter Book. There is debate over whether it means "weary with sleep" or "weary for sleep".

- Lewis Carroll's "Jabberwocky" contains multiple words that appear only once in English, and in a similar vein, James Joyce's Finnegans Wake contains several on each page.

German examples

- The name of the 9th-century poem Muspilli is a back-formation from "muspille", Old High German hapax legomenon of unclear meaning only found in this text (see Muspilli#Etymology for discussion).

Ancient Greek examples

- According to classical scholar Clyde Pharr, "the Iliad has 1097 hapax legomena, while the Odyssey has 868".[18]

- panaōrios (παναώριος), ancient Greek for "very untimely", is one of many words that occur only once in the Iliad.[19]

- The Greek New Testament contains 686 local hapax legomena, which are sometimes called "New Testament hapaxes".[20] 62 of these occur in 1 Peter and 54 occur in 2 Peter.[21]

- Epiousios, translated into English as ″daily″ in the Lord's Prayer in Matthew 6:11 and Luke 11:3, occurs nowhere else in all of the known ancient Greek literature, and is thus a hapax legomenon in the strongest sense.

- The word aphedrōn (ἀφεδρών) "latrine" in the Greek New Testament occurs only twice, in Matthew 15:17 and Mark 7:19, but since it is widely considered that the writer of the Gospel of Matthew used the Gospel of Mark as a source, it may be regarded as a hapax legomenon. It was thought to mean "bowel" until an inscription was found in Pergamos.

Hebrew examples

There are about 1,500 Hapax legomena in the Hebrew Bible; however, due to Hebrew roots, suffixes and prefixes, only 400 are "true" hapax legomena. A full list can be seen at the Jewish Encyclopedia entry for "Hapax Legomena."[12]

Some examples include:

- Akut (אקוט – fought), only appears once in the Hebrew Bible, in Psalms 95:10.

- Atzei Gopher (עֲצֵי-גֹפֶר – Gopher wood) is mentioned once in the Bible, in Genesis 6:14, in the instruction to make Noah's ark "of gopher wood". Because of its single appearance, its literal meaning is lost. Gopher is simply a transliteration, although scholars tentatively suggest that the intended wood is cypress.[22]

- Gvina (גבינה – cheese) is a hapax legomenon of Biblical Hebrew, found only in Job 10:10. The word has become extremely common in modern Hebrew.

- Zechuchith (זכוכית) is a hapax legomenon of Biblical Hebrew, found only in Job 28:17. The word derives from the root זכה z-ch-h, meaning clear/transparent and refers to glass or crystal. In Modern Hebrew, it is used for "glass."

- Lilith (לילית) occurs once in the Hebrew Bible, in Isaiah 34:14, which describes the desolation of Edom. It is translated several ways.

Irish examples

The strength of word building in the structure of the Irish language makes it relatively easy to create words ad hoc. A common wordplay game, played at poetry festivals such as the Galway Arts Festival, is to give short orations or recite short poems using as many hapax legomena as possible.

- chomneibi, an adjective of unknown meaning describing a lath, only appears in Triads of Ireland #169.[23]

Italian examples

- Ramogna is mentioned only once in Italian literature, specifically in Dante's Divina Commedia (Purgatorio XI, 25).

- Trasumanar is another hapax legomenon mentioned in the Divina Commedia (Paradiso I, 70, translated as "Passing beyond the human" by Mandelbaum).

- Ultrafilosofia, which means "beyond the philosophy" appears in Leopardi's Zibaldone (Zibaldone 114–115 – June, 7th 1820).

Latin examples

- Deproeliantis, a participle of the word deproelior, which means "to fight fiercely" or "to struggle violently", appears only in line 11 of Horace's Ode 1.9.

- Mactatu, singular ablative of mactatus, meaning "because of the killing". It occurs only in De rerum natura by Lucretius.

- Mnemosynus, presumably meaning a keepsake or aide-memoire, appears only in Poem 12 of Catullus's Carmina.

- Scortillum, a diminutive form meaning "little prostitute", occurs only in Poem 10 of Catullus's Carmina, line 3.

- Terricrepo, an adjective apparently referring to a thunderous oratory method, occurs only in Book 8 of Augustine's Confessions.

- Romanitas, a noun signifying "Romanism" or "the Roman way" or "the Roman manner", appears only in Tertullian's de Pallio.[24][25]

- Arepo is a word only found in the Sator squares.

Russian examples

- Vytol (вытол) is a hapax legomenon of the known corpus of the Medieval Russian birch bark manuscripts. The word occurs in inscription no. 600 from Novgorod, dated ca. 1220–1240, in the context "[the] vytol has been caught" (вытоло изловили). According to Andrey Zaliznyak, the word does not occur anywhere else, and its meaning is not known.[26] Various interpretations, such as a personal name or the social status of a person, have been proposed.[27]

See also

References

- ↑ "hapax legomenon". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ "hapax legomenon". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House.

- ↑ ἅπαξ. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- ↑ Paul Baker, Andrew Hardie, and Tony McEnery, A Glossary of Corpus Linguistics, Edinburgh University Press, 2006, page 81, ISBN 0-7486-2018-4.

- ↑ András Kornai, Mathematical Linguistics, Springer, 2008, page 72, ISBN 1-84628-985-8.

- ↑ Kirsten Malmkjær, The Linguistics Encyclopedia, 2nd ed, Routledge, 2002, ISBN 0-415-22210-9, p. 87.

- ↑ Christopher D. Manning and Hinrich Schütze, Foundations of Statistical Natural Language Processing,MIT Press, 1999, page 22, ISBN 0-262-13360-1.

- ↑ P.N. Harrison. The Problem of the Pastoral Epistles. Oxford University Press, 1921.

- 1 2 3 Workman, "The Hapax Legomena of St. Paul", Expository Times, 7 (1896:418), noted in The Catholic Encyclopedia, s.v. "Epistles to Timothy and Titus".

- ↑ Steven J. DeRose. "A Statistical Analysis of Certain Linguistic Arguments Concerning the Authorship of the Pastoral Epistles." Honors thesis, Brown University, 1982; Terry L. Wilder. "A Brief Defense of the Pastoral Epistles' Authenticity". Midwestern Journal of Theology 2.1 (Fall 2003), 38–4. (on-line)

- ↑ Mark Harding. What are they saying about the Pastoral epistles?, Paulist Press, 2001, page 12. ISBN 0-8091-3975-8, ISBN 978-0-8091-3975-0.

- 1 2 Article on Hapax Legomena in Jewish Encyclopedia. Includes a list of all the Old Testament hapax legomena, by book.

- ↑ D. Jurafsky and J.H. Martin (2009). Speech and Language Processing. Prentice Hall.

- ↑ Orhan Elmaz. "Die Interpretationsgeschichte der koranischen Hapaxlegomena." Doctoral thesis, University of Vienna, 2008, page 29

- ↑ "flother". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ "Historical Thesaurus :: Search". historicalthesaurus.arts.gla.ac.uk. Retrieved 2017-10-28.

- ↑ Hibbard, ed. by G. R. (1998). Hamlet (Reissued as ... pbk. ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 163. ISBN 9780192834164.

- ↑ Pharr, Clyde (1920). Homeric Greek, a book for beginners. D. C. Heath & Co., Publishers. p. xxii.

- ↑ (Il. 24.540)

- ↑ e.g. Richard Bauckham The Jewish world around the New Testament: collected essays I p431 2008: "a New Testament hapax, which occurs 19 times in Hermas. . ."

- ↑ John F. Walvoord and Roy B. Zuck, The Bible Knowledge Commentary: New Testament Edition, David C. Cook, 1983, page 860, ISBN 0-88207-812-7.

- ↑ "Ark, Design and Size" Aid to Bible Understanding, Watchtower Bible and Tract Society, 1971.

- ↑ http://www.smo.uhi.ac.uk/gaeilge/donncha/focal/features/triads/triad169.html

- ↑ Lewis, C.T. & Short, C. (1879) A Latin Dictionary, Oxford University, Clarendon Press, p.1599.

- ↑ http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/tertullian/tertullian.pallio.shtml

- ↑ Andrey Zaliznyak, Новгородская Русь по берестяным грамотам: взгляд из 2012 г. (The Novgorod Rus' according to its birch bark manuscripts: a view from 2012), transcript of a lecture.

- ↑ А. Л. Шилов (A.L. Shilov), ЭТНОНИМЫ И НЕСЛАВЯНСКИЕ АНТРОПОНИМЫ БЕРЕСТЯНЫХ ГРАМОТ (Ethnonyms and non-Slavic anthroponyms in birch bark manuscripts)

External links

| Look up hapax legomenon in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |