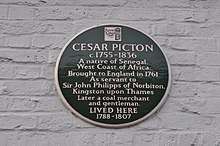

Cesar Picton

Cesar Picton (c. 1755 Senegal? – 1836 Thames Ditton, Surrey) was presumably enslaved in Africa by the time he was about six years old. He was bought and brought to England by an English army officer who had been in Senegal, and in 1761 was "presented" as a servant to Sir John Phillips, a Baronet living in Norbiton near Kingston upon Thames in Surrey. He later became a wealthy coal merchant in Kingston.

Slave to servant

Sir John's journal recorded the arrival of Picton in the household, along with the gift of "a parakeet and a foreign duck". He was rapidly baptised by the Phillips, who were supporters of missionary work – he had quite likely been born into an Islamic family. Initially rigged out as an exotic page-boy, with a velvet turban (cost 10 shillings and sixpence) in the rococo fashion of the day, he became a favourite of the family, especially Lady Phillips. When Picton was about 33, Horace Walpole wrote in a letter of 1788: "I was in Kingston with the sisters of Lord Milford; they have a favourite black, who has been with them a great many years and is remarkably sensible".[1] Lord Milford was the son of the Phillips', who were by then both dead. "Sensible" at this period meant "possessing sensibility", as opposed to the usual modern meaning of calm, down to earth, and the like. He had clearly achieved an unusual status in the household by this stage. Picton took his surname from Picton Castle, Pembrokeshire, the Phillips's country estate in Wales, which was then a significant site for mining coal.[2]

The legal status of slaves imported into England was ambiguous and unclear when Picton arrived, but they were certainly not regarded or treated in the same way as slaves in the British American colonies. The situation was clarified considerably by Somersett's Case of 1772 (when Picton was probably in his late teens), which although the details are unclear when analysed by lawyers, was generally taken to hold than no person could be a slave in England itself (confirming other reported judgements of 1567 and 1702). Many white apprentices and workers of the time would be classified as near-slaves, though in a time-limited way, by modern standards, and by the time of the case most black servants seem already to have been regarded and treated as free, at least by the time they reached adulthood.

Tradesman to gentleman

Following the deaths of Sir John in 1764, and his wife in 1788, and the sale of Norbiton Place by their son, Picton used a legacy of £100 from Lady Phillips to set up in business as a coal merchant in nearby Kingston. The move from servant to tradesman was a common one; Picton was presumably well-known to the owners and upper servants of the many large houses in the area after nearly thirty years at Norbiton. The three unmarried Phillips daughters had moved to nearby Hampton Court on the sale of the house, and since they all later left him legacies (in total by 1820, £250 and £30 a year), they may well have been ready to push their friends to buy coal from him. In the phrase of the day, he had "connections". In addition, it is probably no coincidence that the Phillips's estate at Picton was a centre of coal mining; he may well have sourced his supplies from them, to mutual advantage, and perhaps had already been involved in managing their affairs.

Picton was successful in business and became rich, in great contrast to the majority of black people in Britain at the time who lived in extreme poverty, working in subsistence pay occupations or in ambiguous conditions of enslavement. Later black people to achieve more modest economic success in trades included William Cuffay and William Davidson who earned their money as skilled professional tailor and cabinet-maker respectively.[3] In 1731 the Corporation of London banned the apprenticing of black men, so opportunities for professional success were limited.[4] Other successful black businessmen of the time often worked as publicans and lodging-house keepers and this provides some evidence of their limited upward social mobility.[3] Picton's wealth is well documented and he is often cited as the best-known example of black financial success of the thousands of black persons in Britain at the time.

His original premises at 52 High Street, Kingston Upon Thames backs onto the River Thames and has since been known as Picton House, apart from the four years between 1981 and 1985, when it was headquarters of Amari Plastics Ltd and known as Amari House.[5] The building is mid-ranked in terms of listing at Grade II* and is marked with a blue plaque.[6][7] Picton had lived there for the first years of his business, initially renting, but in 1795 buying it and other property including a wharf onto the Thames for unloading the coal, and a malthouse.

In 1801 Picton was convicted for poaching with an unlicensed gun and fined five pounds.[8] The fine was relatively trivial for Picton and someone of lower social status may have faced execution or transportation to Australia for the same offence. Picton appealed the decision using the services of a London attorney, who challenged the conviction on the grounds that the magistrate's record of the year of the offence was incorrectly recorded. The King's Bench held that this was "surplusage" and not material to the validity of the case, so the conviction was upheld. Picton's race was not mentioned in the judgement nor the report of the appeal that appeared in The Morning Post.[9][10]

In 1807 Picton let his Kingston properties and moved to a rented house in Tolworth, perhaps marking his retirement at 52 from active trade. He was by then described in deeds as a "gentleman" and by 1816 he bought a house with large garden, both dwarfing their neighbour, in central Thames Ditton for an above-average £4,000 (in theory equivalent to £280,991 in 2016, though a house of that size in that location would now cost many times that).[11] He died in 1836 at the age of 81 and is buried in All Saints Church, Kingston upon Thames— he was evidently a very large man as a four-wheeled trolley was needed for the coffin.

Legacy

Picton left a portrait of himself in his will (along with several other paintings), but its whereabouts are not known. It emerged in 2007 that the portrait used as his in a mural of Kingston's history commissioned by the Council was actually of either Olaudah Equiano or, possibly Ignatius Sancho.[12] He is not known to have married, and all his bequests were to friends, including 16 mourning rings. Although Picton lived through the main period of the British abolitionist movement, no involvement by him is known.

A blue plaque commemorating Cesar Picton has been mounted on his former home, Picton House in Thames Ditton.[13] A meeting and reception room, the 'Picton Room', at Kingston University is named in Picton's honour.[14]

Picton is a character in the children's novel Jupiter Williams by S.I. Martin, set in 1800.[15]

During Picton's time in Kingston, the area also gave rise to a significant legal case related to slavery in R[ex] v Inhabitants of Thames Ditton of 1785, where Lord Mansfield (previously the judge in Somersett's Case) held that Charlotte Howe, a former slave, was not entitled to pay for her previous work, in the absence of a specific contract.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Walpole, Horace (1891). Cunningham, Peter, ed. 2451. To the Countess of Ossory, Strawberry Hill, Oct. 19, 1788. The Letters of Horace Walpole, Fourth Earl of Orford IX (London: Richard Bentley ad Son). p. 107.

- ↑ "Archaeology in Wales". Archived from the original Archived 4 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine. on 15 July 2004. Retrieved 25 March 2007.

- 1 2

- Myers, Norma (1996). Reconstructing the Black past: Blacks in Britain, c. 1780–1830, (reprint), Routledge. p. 77. ISBN 0-7146-4575-3, ISBN 978-0-7146-4575-9

- ↑ Crais, Clifton C.; Scully, Pamela (2009). Sara Baartman and the Hottentot Venus: A Ghost Story and a Biography. Princeton University Press. p. 67. ISBN 9780691135809.

- ↑ Our History | Amari Archived 24 August 2015 at the Wayback Machine.. Amari Plastics. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- ↑ Historic England. "Picton House, Kingston upon Thames (Grade II*) (1080069)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ↑ Benge, Howard. Cesar Picton, A Black Merchant In 18th Century Kingston. Archived from the original on 8 January 2007. Retrieved 3 June 2007.

- ↑ East, Edward Hyde (1817). Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Court of King’s Bench 2 (second ed.). p. 198.

- ↑ Chater, Kathleen. Cesar Picton’s Conviction for Poaching. History department, Kingston University. 15 April 2015. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

- ↑ "Law Intelligence". The Morning Post. 4 February 1802. p. 3.(subscription required)

- ↑ Historic England. "Picton House, Thames Ditton (Grade II) (1190732)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- ↑ I came, I saw, I blundered page 1 lead story, The Kingston Informer, 23 March 2007.

- ↑ "Cesar Picton, Slave to Gentleman". Your Local Guardian. 31 March 2012.

- ↑ Africans in Georgian London: Cesar Picton and his World in Film and Records. Kingston University. Retrieved 10 September 2015

- ↑ Martin, S.I. (4 October 2007). Jupiter Williams. Hodder. ISBN 978-0340944066.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cesar Picton. |

- Jane Austen's World feature on Picton