Tel Yokneam (Qamun)

| תֵּל יָקְנְעָם | |

|

Tel Yokneam seen from the Mount Carmel with the modern city of Yokneam Illit on the right and the modern town of Yokneam Moshava on the left. | |

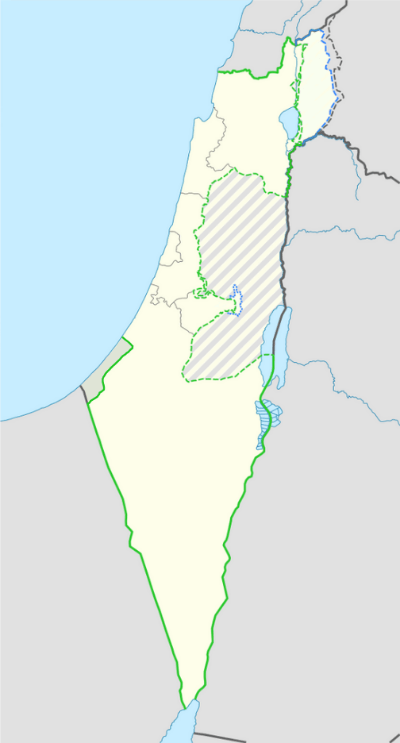

Shown within Israel | |

| Location |

|

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 32°39′51″N 35°06′6.3″E / 32.66417°N 35.101750°ECoordinates: 32°39′51″N 35°06′6.3″E / 32.66417°N 35.101750°E |

Tel Yokneam is a tell located between the modern city of Yokneam Illit and the town of Yokneam Moshava. In Arabic, and for most part of history the place was known as a variation of the name Qamun or Tell Qamun. It is believed to be a corruption Hebrew name.[1] The site spans around 40 dunams,[2] rising steeply to a height of 60 meters.[3]

Yokneam was settled, with short breaks, from the Early Bronze Age, to the Mamluk Sultanate era, i.e, close to 4,000 years.[4] The city is first mentioned in Egyptian scripts as a city conquered by Pharaoh Thutmose III and later in the Hebrew Bible as a city defeated by Israelite leader Joshua, setted by the Israelite Tribe of Levi. It is mentioned twice in Roman scripts and the remains of a church from the Byzantine era is found there. During the Crusader period the settlement was called Caymont and was for a while, the center of a Seignory, the smallest of all in the history of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. In the 13th century the settlement was captured by the Muslim Mamluks. It is possible that during the Ottoman period, a fort was built was built in the site, but this is not fully confirmed.[5]

Etymology

The origin of the name "Yokneam" (Hebrew: Hebrew: יָקְנְעָם) is Hebrew, from the Old Testament. During Canaanite periods it was probably called something like Anaknam, as it appears in the lists of 119 cities conquered by Pharaoh Thutmose III.[6]

Edward Robinson argued in 1856 that Qamun or Kaimôn may be a corruption of the Hebrew name. By his theory, the Yod was dropped, the guttural Koph was retained and the Ayin sound "may well have disappeared through the medium of the Galilean dialect, which confounded Aleph, Heth and Ayin."[1]

The Crusaders transformed its name, so as to read, Cain Mons ("Mount Cain"), recalling the tradition that it was the site of Cain's killing as described in the Book of Genesis' Song of Lamech. Writing in the latter half of the 19th century, Claude R. Conder in Tent Work in Palestine: A Record of Discovery and Adventure notes that a local chapel in Keimun "shows the spot once held to be the site of the death of Cain."[7]

History

Bronze Age

The earliest stratum (layer) reached in the excavations in Tel Yokneam, is from the Middle Bronze Age (2000 BCE – 1550 BCE), although this is probably not the earliest stratum, and potsherds found in the site indicated that the Yokneam was settled already in the Early Bronze Age (3300 BCE – 2000 BCE).[3]

The remains of the settlement from the Middle Bronze Age were found in the edges of the northern part of the tell. What may be the foundation of a stone or dirt wall was found, indicating the settlement may have been fortified. A house, with a system of rooms and a backyard. In the house, an abundance of ceramics indicate that it is from the 17th to 16th centuries BCE. The residents of this house buried the dead, especially the children, under the house floor, in jars. A beetle stamp was found on a bowl with the name of pharaoh Amenemhat III (reign: 1860–1814 BCE).[3]

The city is mentioned as "Ankana'am" in the list of cities that Pharaoh Thutmose III conquered in his campaign in the 15th century BCE[8] Findings from the Late Bronze Age include four stages of construction from the 15th to 13th centuries BCE. The city's houses were found well preserved and within them an abundance of pottery some of it is from either from foreign lands, such as Cyprus, Mycenae. Two Egyptian tools were found, but it was not clear if these are original or locally made copies. Jewelry typical of the Mitanni culture were found. The city was destroyed in a large fire somewhere between the second half of the 13th century BCE to the beginning of the 12th century BCE.[9]

Iron Age

Yokneam mentioned three times in the Hebrew Bible, all in the Book of Joshua. It first appears in a list of thirty one city-states defeated by Joshua and the Israelites.[10] Later, it is mentioned as a city in the territory of the Tribe of Zebulun, settled by members of the Merarites family of the Tribe of Levi.[11]

After the destruction in the end of the Late Bronze Age, the city was rebuilt somewhere between the 12th century BCE to the early 11th century BCE. It seems the reconstruction of the city took place a few decades after the destruction. The Iron Age city has three distinct periods.[12] In the first one, locally made Canaan tools and pottery, characteristic of the Late Bronze Age were the majority of the findings, but some from Phoenician and Philistine origin were also found.[13] One notable structure from that period is nicknamed the "House of Oil", as the tools and olive seeds found in it indicate it was an oil mill. The house is connected to a cave, in which the residents buried their dead.[12] This city was razed in a large fire, which is probably attributed to the conquests of Israelite king David. For a few decades the city was in a very poor until it was rebuilt in the 10th century BCE. In this century a 5m wide fortifications system was built from stones imported from the nearby Mount Carmel. A drainage system was installed to protect the fortifications from rain.[13] The wall reached a height of at least 4 m (13 ft). Yokneam was razed and resettled again in the 9th century BCE.[14] The most probable reason for the destruction is the invasion of Aram-Damascus under King Hazael (reign: 842 BCE–796 BCE). The city was rebuilt during the occupation.[15] The new city had a new double-wall system. Because of the city's location on the border between the Kingdom of Israel and Phoenicia, its fortifications during the Iron Age are much stronger than the ones in nearby Megiddo. The end of this period in the city's history came with the Assyrian invasion under king Tiglath-Pileser III in 732 BCE.[14] After the occupation, only a small settlement remained, and the fortifications were no longer in use. The identity of the residents is unknown, but they lived there between the end of the 8th century BCE and the 7th century BCE.[14]

Persian period

In 539 BCE the Achaemenid Empire under Cyrus the Great conquered the Babylonian Empire and thus took over the Levant, along with Yokneam. Although Yokneam doesn't appear in sources from the Persian period, there was a dense city. A few Phoenician styled buildings, which probably served as warhouses were discovered. The rooms were filled with a lot of pottery, which indicating the city was razed suddenly.[14] Personal names found written on pottery there include names of Hebrew, Persian and Phoenician origin, indicating Yokneam was a cosmopolitan city during the Persian period.[16] The city was settled throughout the entire Persian period, from the late 6th century BCE to the 4th century BCE.[17]

Hellenistic period

Very little findings from the Hellenistic period were found in Yokneam. An Hellenistic square shaped watch-tower was found in the northern part of the tell. The tower has deep foundations and it overlooked the junction of two international routes in the foot of the tell. This site is dated to the 2nd century BCE. Most of the pottery was found in a sewage pit. Among the potsherds were parts of wine jars from the island of Rhodes. The abundance of pottery indicate there was a settlement in that period, but it was not found in the excavations.[17]

Roman and Byzantine city

Only potsherds were found from the Roman settlement were found.[17] Eusebius of Caesarea included biblical Yokneam in his Onomasticon in the 3rd century AD and wrote that at his time it was a village called "Cammona" "situated in the great plain, six Roman miles north of Legio, on the way to Ptolemais".[18][1] The Roman settlement was not found, but pottery from that period suggests there was a settlement there in the 4th century AD.[17] The survey did find a Byzantine church, built between the 4th century and the 7th century AD.[19]

Early Arab period

Although not mentioned in sources, Yokneam at that time was a well planned city, with a street system and symmetrical buildings built on terraces. The buildings from that period were found in the northwestern side of the tell and are dated to the second half of the 9th century and the first half of the 10th century.[17] Ceramics from this period are some of the most luxurious of their time, and they indicate the city was established around the 9th century, probably during the rule of Ahmad ibn Tulun, who united Egypt, Syria and the Levant under his rule in 878. Ceramics from the Umayyad period (661–750) were discovered but a settlement from that period wasn't found. There are no signs of destruction, and it was suggested the city was abandoned in the 9th century for an unknown reason.[20]

Crusader, Ayyubid and Mamluk periods

In 1099, after the First Crusade, the site was included in the newly established Kingdom of Jerusalem. At that period Yokneam was a village owned by the monastery of Mount Tabor, as it appears in a July 1103 list, named Caimun in terra Acon. It was also probably a frankish settlement. Yokneam, known back then as "Caymont" and "Cain Mons", became a center of a lordship. Among the lords of Caymont are "Joscelin" (mentioned between 1139–1145), "Walter" (mentioned in 1152) and "William" (mentioned between 1182–1199).[21][19] Caymont was the smallest of the seignories, its territory didn't exceed more than 50 square km and no other settlements in its territory are known.[20]

Crusader Yokneam was a fortified city with an acropolis on the southern side of the tell, which is the highest. In the acropolis there is a castle with a watchtower.[20] The castle is attributed to king Baldwin I of Jerusalem (reign: 1100–1118). In the lower part of the acropolis, a church is found, which was built on the earlier Byzantine church.[21] A wall surrounded all of the city. Pottery from this period included locally made dishes and tools, but also some imported.[22]

After Saladin defeated the armies of the Crusaders in the battle of Battle of Hattin (1187), Yokneam fell to the hands of the Ayyubids. In 1191 Saladin camped there during his march towards the city of Ascalon.[21] Imad ad-Din Zengi wrote that Saladin planned to destroy the walls of Acre and to fortify Caymont instead,[20] but following the Treaty of Jaffa in 1192, Saladin returned the castle and its territory to the Franks. It was given to Balian of Ibelin, who owned it for one year until his death in 1193. In the mid 13th century there was a dispute between the Hospitallers and the Templars over the ownership of the territory. The dispute was solved in May 1262, with the Templars winning over the territory. Yokneam was likely attacked by Mamluk sultan Baibars somewhere between 1263 and 1266. It was confirmed in 1283 that the territory is under the Muslim hands of Al-Mansur Qalawun.[23][21]

The remains of a Mamluk settlement were found in the area of the church.[22]

Ottoman period

Historical records from the 18th century say that Zahir al-Umar, who ruled over the Galilee in that century, built a fortress in Yokneam. Besides some smoking pipes no other remains of the Ottoman period were found.[5]

Charles William Meredith van de Velde described the place in 1854. He noted the presence of ruins there, including the foundations of a Christian church, and several large vaulted caves. He described the area as a "deserted region. Here are no more armies, no more townspeople or villages; a single herd of goats watched by a few wild Arabs, was all we met."[24]

Claude Reignier Conder described the place in 1878 as a "huge tell" with the remains of a "chapel" and a "small fort" built by Zahir al-Umar. He tells about two legends about this place, a Samaritan legend about Joshua, and a Christian legend, according to which, Lemech, the great grandchild of Cain, murdered his own great grandfather here with an arrow. Condor refers to the name "Cain Mons" as a corruption of the name "Keimûn" (i.e. Caymont).[25]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Robinson, 1856, p. 115.

- ↑ Feig, Nurit (6 December 2016). "Volume 128 Year 2016: Yoqneʽam". Hadashot Arkheologiyot - Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Israel Antiquities Authority.

- 1 2 3 Ben Tor, p.4

- ↑ Ben Tor, p.2

- 1 2 Ben Tor, p.12

- ↑ "Tel Yokneam". BibleWalks.com.

- ↑ Conder, 1878, p. 131

- ↑ Aharoni, Yohanan, Carta's Atlas of The Bible, Jerusalem: Carta, Beit Hadar, 1974, p.33

- ↑ Ben Tor, p.5

- ↑ Book of Joshua, 12:22

- ↑ Book of Joshua, 19:11, 21:34

- 1 2 Ben Tor, p.6

- 1 2 Ben Tor, p.7

- 1 2 3 4 Ben Tor, p.8

- ↑ Ghantous, Hadi (2014). The Elisha-Hazael Paradigm and the Kingdom of Israel: The Politics of God in Ancient Syria-Palestine. Routledge. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-84465-739-1.

- ↑ Prof. Rappoport, Uriel; Dr. Yaron, Shlomit (2004). From Cyrus to Alexander: The Jews Under Persian Rule (in Hebrew). Open University of Israel. p. 188. ISBN 965-06-0764-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ben Tor, p.9

- ↑ Eusebius of Caesarea, Onomasticon, Translated by C. Umhau Wolf (1971), Section K, Josua

- 1 2 J.Boas, Adrian (2017). Crusader Archaeology: The Material Culture of the Latin East. Routledge. p. 114. ISBN 978-1-138-90025-7.

- 1 2 3 4 Ben Tor, p.10

- 1 2 3 4 Pringle, Denys (1998). The churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem : a corpus. Vol.2, L-Z. Cambridge University. pp. 159–160. ISBN 0-521-39037-0.

- 1 2 Ben Tor, p.11

- ↑ Runciman, 1987, p. 86

- ↑ Van de Velde, 1854, vol. 1, p. 331

- ↑ Condor, pp.130–131

Bibliography

- Ben Tor, Amnon; Avissar, Miryam; Bonfil, Ruhamma; Zerzetsky, Anbel; Portugali, Yuval (1987). "A Regional Study of Tel Yoqneʿam and Its Vicinity /מחקר אזורי בתל יקנעם וסביבתו". Qadmoniot: A Journal for the Antiquities of Eretz-Israel and Bible Lands /קדמוניות: כתב-עת לעתיקות ארץ-ישראל וארצות המקרא (in Hebrew). Israel Exploration Society. 78-77: 2–17. JSTOR 23677912.

- Robinson, Edward (1856). Later Biblical Researches in Palestine, and in the Adjacent Regions. Harvard University.

- Schwarz, Joseph; Schwarz, Leeser (1850). A descriptive geography and brief historical sketch of Palestine. Oxford University.

- Velde, van de, Charles William Meredith (1854). Narrative of a journey through Syria and Palestine in 1851 and 1852. 1. William Blackwood and son.

- Runciman, Steven (1987). A history of the crusades. 3. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521347726.

- Conder, C. R. (Claude Reignier) (1878). Tent work in Palestine. A record of discovery and adventure Vol. 1. London R. Bentley & Son.