Cattle in religion and mythology

Due to the multiple benefits from cattle, there are varying beliefs about cattle in societies and religions. In some regions, especially Nepal and most states of India, the slaughter of cattle is prohibited and their meat may be taboo.

Cattle are considered sacred in world religions such as Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, and others. Religions in ancient Egypt, ancient Greece, ancient Israel, ancient Rome, and ancient Germany held similar beliefs.

In Indian religions

Sri Lanka is the first country in South Asia to completely legislate on harm inflicted against cattle. Sri Lanka currently bans the sale of cattle for meat throughout all of the island, following a legislative measure that united the two main ethnic groups on the island (Tamils and Sinhalese)[1], whereas legislation against cattle slaughter is in place throughout most states of India except Kerala, West Bengal, and parts of the North-East.[2]

Hinduism

Majority of scholars explain the veneration for cows among Hindus in economic terms, which includes the importance of dairy in the diet, use of cow dung as fuel and fertilizer, and the importance that cattle have historically played in agriculture.[3] Ancient texts such as Rig Veda, Puranas highlight the importance of the cattle.[3] The scope, extent and status of cows throughout during ancient India is a subject of debate. According to D. N. Jha, cattle including cows were neither inviolable nor revered in the ancient times as they were later.[4] A Gryhasutra recommends that beef be eaten by the mourners, after a funeral ceremony as a ritual rite of passage.[5] In contrast, according to Marvin Harris, the Vedic literature is contradictory, with some suggesting ritual slaughter and meat consumption, while others suggesting a taboo on meat eating.[6]

The Chandogya Upanishad (~ 800 BCE) mentions the ethical value of Ahimsa, or non-violence towards all beings.[7][8] By mid 1st millennium BCE, all three major Indian religions – Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism – were championing non-violence as an ethical value, and something that impacted one's rebirth. According to Harris, by about 200 CE, food and feasting on animal slaughter were widely considered as a form of violence against life forms, and became a religious and social taboo.[6][9]

Milk cows are called aghnya "that which may not be slaughtered" in Rigveda. Yaska, the early commentator of the Rigveda, gives nine names for cow, the first being "aghnya".[10]

According to Nanditha Krishna, the cow veneration in ancient India during the Vedic era, the religious texts written during this period called for non-violence towards all bipeds and quadrupeds, and often equated killing of a cow with the killing of a human being especially a Brahmin.[11] Nanditha Krishna stated that the hymn 10.87.16 of the Hindu scripture Rigveda (~1200–1500 BCE) condemns all killings of men, cattle, and horses, and prays to god Agni to punish those who kill.[12][13]

Many ancient and medieval Hindu texts debate the rationale for a voluntary stop to cow slaughter and the pursuit of vegetarianism as a part of a general abstention from violence against others and all killing of animals.[14][15] According to Harris, the literature relating to cow veneration became common in 1st millennium CE, and by about 1000 CE vegetarianism, along with a taboo against beef, became a well accepted mainstream Hindu tradition.[6] This practice was inspired by the beliefs in Hinduism that a soul is present in all living beings, life in all its forms is interconnected, and non-violence towards all creatures is the highest ethical value.[6][9] Vegetarianism is a part of the Hindu culture. The god Krishna and his Yadav kinsmen are associated with cows, adding to its endearment.[6][9]

According to Ludwig Alsdorf, "Indian vegetarianism is unequivocally based on ahimsa (non-violence)" as evidenced by ancient smritis and other ancient texts of Hinduism. He adds that the endearment and respect for cattle in Hinduism is more than a commitment to vegetarianism and has become integral to its theology.[16] The respect for cattle is widespread but not universal. According to Christopher Fuller, animal sacrifices have been rare among the Hindus outside a few eastern states.[16][17] To the majority of modern Indians, states Alsdorf, respect for cattle and disrespect for slaughter is a part of their ethos and there is "no ahimsa without renunciation of meat consumption".[16]

The interdiction of the meat of the bounteous cow as food was regarded as the first step to total vegetarianism.[18]

- Puranas

The earth-goddess Prithvi was, in the form of a cow, successively milked of beneficent substances for the benefit of humans, by deities starting with the first sovereign: Prithu milked the cow to generate crops for humans to end a famine.[19]

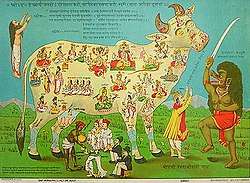

Kamadhenu, the miraculous "cow of plenty" and the "mother of cows" in certain versions of the Hindu mythology, is believed to represent the generic sacred cow, regarded as the source of all prosperity.[20] In the 19th-century, a form of Kamadhenu was depicted in poster-art that depicted all major gods and goddesses in it.[21][22]

Historical significance

The reverence for the cow played a role in the Indian Rebellion of 1857 against the British East India Company. Hindu and Muslim sepoys in the army of the East India Company came to believe that their paper cartridges, which held a measured amount of gunpowder, were greased with cow and pig fat. The consumption of swine is forbidden in Islam and Judaism. Because loading the gun required biting off the end of the paper cartridge, they concluded that the British were forcing them to break edicts of their religion.[24]

A historical survey of major communal riots in India between 1717 and 1977 revealed that 22 out of 167 incidents of rioting between Hindus and Muslims were attributable directly to cow slaughter.[25][26]

In Gandhi's teachings

The cow protection was a symbol of animal rights and of non-violence against all life forms for Gandhi. He venerated cows, and suggested ending cow slaughter to be the first step to stopping violence against all animals.[27] He said: "I worship it and I shall defend its worship against the whole world", and stated that "The central fact of Hinduism is cow protection."[27]

Jainism

Jainism is against violence to all living beings, including cattle. According to the Jaina sutras, humans must avoid all killing and slaughter because all living beings are fond of life, they suffer, they feel pain, they like to live, and long to live. All beings should help each other live and prosper, according to Jainism, not kill and slaughter each other.[28][29]

In the Jain religious tradition, neither monks nor laypersons should cause others or allow others to work in a slaughterhouse.[30] Jains believe that vegetarian sources can provide adequate nutrition, without creating suffering for animals such as cattle.[30] According to some Jain scholars, slaughtering cattle increases ecological burden from human food demands since the production of meat entails intensified grain demands, and reducing cattle slaughter by 50 percent would free up enough land and ecological resources to solve all malnutrition and hunger worldwide. The Jain community leaders, states Christopher Chapple, has actively campaigned to stop all forms of animal slaughter including cattle.[31]

Buddhism

The texts of Buddhism state ahimsa to be one of five ethical precepts, which requires a practicing Buddhist to "refrain from killing living beings".[32] Slaughtering cow has been a taboo, with some texts suggest taking care of a cow is a means of taking care of "all living beings". Cattle is seen in Buddhism as a form of reborn human beings in the endless rebirth cycles in samsara, protecting animal life and being kind to cattle and other animals is good karma.[32][33] Not only do Buddhist texts state that killing or eating meat is wrong, it urges Buddhist laypersons to not operate slaughterhouses, nor trade in meat.[34][35][36] Indian Buddhist texts encourage a plant-based diet.[9][6]

According to Saddhatissa, in the Brahmanadhammika Sutta, the Buddha "describes the ideal mode of life of Brahmins in the Golden Age" before him as follows:[37]

Like mother (they thought), father, brother or any other kind of kin,

cows are our kin most excellent from whom come many remedies.

Givers of good and strength, of good complexion and the happiness of health,

having seen the truth of this cattle they never killed.

Those brahmins then by Dharma did what should be done, not what should not,

and so aware they graceful were, well-built, fair-skinned, of high renown.

While in the world this lore was found these people happily prospered.

Saving animals from slaughter for meat, is believed in Buddhism to be a way to acquire merit for better rebirth.[33] According to Richard Gombrich, there has been a gap between Buddhist precepts and practice. Vegetarianism is admired, states Gombrich, but often it is not practiced. Nevertheless, adds Gombrich, there is a general belief among Theravada Buddhists that eating beef is worse than other meat and the ownership of cattle slaughterhouses by Buddhists is relatively rare.[40][note 1]

Zoroastrianism

The term geush urva means "the spirit of the cow" and is interpreted as the soul of the earth. In the Ahunavaiti Gatha, Zarathustra (or Zoroaster) accuses some of his co-religionists of abusing the cow.[42] Ahura Mazda tells Zarathustra to protect the cow.[42]

The lands of Zarathustra and the Vedic priests were those of cattle breeders.[43] The 9th chapter of the Vendidad of the Avesta expounds the purificatory power of gōmēz – cow urine.[44] It is declared to be a panacea for all bodily and moral evils,[44] understood as which it features prominently in the 9-night purification ritual Barashnûm.

Judaism

According to the Hebrew Bible, an unblemished red cow was an important part of ancient Jewish rituals. The cow was sacrificed and burned in a precise ritual, and the ashes were added to water used in the ritual purification of a person who had come in to contact with a human corpse. The ritual is described in the Book of Numbers in Chapter 19, verses 1–14.[45]

Observant Jews study this passage every year in early summer as part of the weekly Torah portion called Chukat. A contemporary Jewish organization called the Temple Institute is trying to revive this ancient religious observance.[46]

Traditional Judaism considers beef kosher and permissible as food,[47] as long as the cow is slaughtered in a religious ritual called shechita, and the meat is not served in a meal that includes any dairy foods.[48]

Some Jews committed to Jewish vegetarianism believe that eating beef is prohibited.[49]

Islam

Islam allows the slaughter of cows and consumption of beef, as long as the cow is slaughtered in a religious ritual called dhabīḥah or zabiha similar to the Jewish shechita.

Although slaughter of cattle plays a role in a major Muslim holiday, Eid al-Adha, many rulers of the Mughal Empire had imposed a ban on the slaughter of cows owing to the large Hindu and Jain populations living under their rule.[50]

The second and longest surah of the Quran is named Al-Baqara ("The Cow"). Out of the 286 verses of the surah, 7 mention cows (Al Baqarah 67–73).[51][52] The name of the surah derives from this passage in which Moses orders his people to sacrifice a cow in order to resurrect a man murdered by an unknown person.[53] Per the passage, the "Children of Israel" quibbled over what kind of cow was meant when the sacrifice was ordered.[54] Classical Sunni and Shia commentators recount several variants of this tale. Per some of the commentators though any cow would have been acceptable but after they "created hardships for themselves" and the cow was finally specified, it was necessary to obtain it any cost.[55]

Ancient Egypt

The ancient Egyptians sacrificed animals but not the cow, because it was sacred to goddess Hathor, and due to the contemporary Greek myth of Io, who had the form of a cow.[56]

In Egyptian mythology, Hesat was the manifestation of Hathor, the divine sky-cow, in earthly form. Like Hathor, she was seen as the wife of Ra. In hieroglyphs, she is depicted as a cow with a headdress.

Ancient Europe

- In Celtic mythology, the cattle goddess was known as Damona in Celtic Gaul and Boann in Celtic Ireland.

- In Greek mythology, the Cattle of Helios pastured on the island of Thrinacia, which is believed to be modern Sicily. Helios, the sun god, is said to have had seven herds of oxen and seven flocks of sheep, each numbering fifty head. A hecatomb was a sacrifice to the gods Apollo, Athena, and Hera, of 100 cattle (hekaton = one hundred).

- In Norse mythology, the primeval cow Auðumbla suckled the ancestor of the Frost Giants, Ymir, and licked Odin's grandfather, Búri, out of the ice.

- Among the Visigoths, the oxen pulling the wagon with the corpse of Saint Emilian lead to the correct burial site (San Millán de la Cogolla, La Rioja).

Modern day

Today, in Hindu-majority countries like India and Nepal, bovine milk holds a key part of religious rituals. For some, it is customary to boil milk on a stove or lead a cow through the house as part of a housewarming ceremony. In honor of their exalted status, cows often roam free, even along (and in) busy streets in major cities such as Delhi. In some places, it is considered good luck to give one a snack or fruit before breakfast.

In India

Constitution of India mandates the protection of cows in India.[3] The slaughter of cattle is allowed with restrictions (like a 'fit-for-slaughter' certificate which may be issued depending on factors like age and gender of cattle, continued economic viability, etc.), but only for bulls and buffaloes and not cows in fourteen states. It is completely banned in six states with pending litigation in the supreme court to overturn the ban, while there is no restriction in many states.[57] This has created communal disharmony in India and frequently leads to unwanted incidents.

Gopastami, a holiday celebrated by the Hindus once a year, is one of the few instances where cows receive prayers in modern-day India.[58] While the cow is still respected and honored by most of the Indian population, there has been controversy over the treatment of the cows during the holiday. Because cow slaughtering is only legal in two Indian states, cows must be transported around the country in rather poor conditions, usually train or by foot.[59] This lack of sacredness toward the cows alarms many animal activists and some dedicated Hindus.

In Nepal

In Nepal, the cow is the national animal. Cows give milk from which the people produce dahi (yogurt), ghee, butter, etc. In Nepal, a Hindu-majority country, slaughtering of cows and bulls is completely banned.[60] Cows are considered like the Goddess Lakshmi (goddess of wealth and prosperity). The Nepalese have a festival called Tihar (Diwali) during which, on one day called Gaipuja, they perform prayers for cows.

According to a Lodi News-Sentinel news story written in the 1960s, in then contemporary Nepal an individual could serve three months in jail for killing a pedestrian, but one year for injuring a cow, and life imprisonment for killing a cow.[61]

Cows roam freely and are sacred. Buffalo slaughtering was done in Nepal at specific Hindu events, such as at the Gadhimai festival, last held in 2014.[62][63] In 2015, Nepal's temple trust on announced to cancel all future animal sacrifice at the country's Gadhimai festival.[64]

In Myanmar

The beef taboo is fairly widespread in Myanmar, particularly in the Buddhist community. In Myanmar, beef is typically obtained from cattle that are slaughtered at the end of their working lives (16 years of age) or from sick animals.[65] Cattle is rarely raised for meat; 58% of cattle in the country is used for draught animal power (DAP).[65] Few people eat beef, and there is a general dislike of beef (especially among the Bamar and Burmese Chinese),[66][67] although it is more commonly eaten in regional cuisines, particularly those of ethnic minorities like the Kachin.[68] Buddhists, when giving up meat during the Buddhist (Vassa) or Uposatha days, will forego beef first.[69] Almost all butchers are Muslim because of the Buddhist doctrine of ahimsa (no harm).[70]

During the country's last dynasty, the Konbaung dynasty, habitual consumption of beef was punishable by public flogging.[71]

In 1885, Ledi Sayadaw, a prominent Buddhist monk wrote the Nwa-myitta-sa (နွားမေတ္တာစာ), a poetic prose letter that argued that Burmese Buddhists should not kill cattle and eat beef, because Burmese farmers depended on them as beasts of burden to maintain their livelihoods, that the marketing of beef for human consumption threatened the extinction of buffalo and cattle, and that the practice and was ecologically unsound.[72] He subsequently led successful beef boycotts during the colonial era, despite the presence of beef eating among locals, and influenced a generation of Burmese nationalists in adopting this stance.[72]

On 29 August 1961, the Burmese Parliament passed the State Religion Promotion Act of 1961, which explicitly banned the slaughtering of cattle nationwide (beef became known as todo tha (တိုးတိုးသား); lit. hush hush meat).[73] Religious groups, such as Muslims, were required to apply for exemption licences to slaughter cattle on religious holidays. This ban was repealed a year later, after Ne Win led a coup d'état and declared martial law in the country.

In Sri Lanka

In Sri Lanka, in May 2013, 30-year-old Buddhist monk Bowatte Indrarathana Thera of the Sri Sugatha Purana Vihara self immolated to protest the government allowing religious minorities to slaughter cows.[74]

China

A beef taboo in Ancient China, known as niú jiè (牛戒), was historically a dietary restriction, particularly among the Han Chinese, as oxen and buffalo (bovines) are useful in farming and are respected.[75] During the Zhou Dynasty, they were not often eaten, even by emperors.[76] Some emperors banned killing cows.[77][78] Beef is not recommended in Chinese medicine, as it is considered a hot food and is thought to disrupt the body's internal balance.[79]

In written sources (including anecdotes and Daoist liturgical texts), this taboo first appeared in the 9th to 12th centuries (Tang-Song transition, with the advent of pork meat.[80]) By the 16th to 17th centuries, the beef taboo had become well accepted in the framework of Chinese morality and was found in morality books (善書), with several books dedicated exclusively to this taboo.[80] The beef taboo came from a Chinese perspective that relates the respect for animal life and vegetarianism (ideas shared by Buddhism, Confucianism, and Daoism, and state protection for draught animals.[80]) In Chinese society, only ethnic and religious groups not fully assimilated (such as the Muslim Huis and the Miao) and foreigners consumed this meat.[80] This taboo, among Han Chinese, led Chinese Muslims to create a niche for themselves as butchers who specialized in slaughtering oxen and buffalo.[81]

Occasionally, some cows seen weeping before slaughter are often released to temples nearby.[82]

Japan

Historically, there was a beef taboo in Ancient Japan, as a means of protecting the livestock population and due to Buddhist influence.[83] Meat-eating had long been taboo in Japan, beginning with a decree in 675 that banned the consumption of cattle, horses, dogs, monkeys, and chickens, influenced by the Buddhist prohibition of killing.[84] In 1612, the shogun declared a decree that specifically banned the killing of cattle.[84]

This official prohibition was in place until 1872, when it was officially proclaimed that Emperor Meiji consumed beef and mutton, which transformed the country's dietary considerations as a means of modernizing the country, particularly with regard to consumption of beef.[84] With contact from Europeans, beef increasingly became popular, even though it had previously been considered barbaric.[83]

Indonesia

In Kudus, Indonesia, Muslims still maintain the tradition of not slaughtering or eating cows, out of respect for their ancestors, who were Hindus, allegedly imitating Sunan Kudus who also did as such.

Leather

In religiously diverse countries, leather vendors are typically careful to clarify the kinds of leather used in their products. For example, leather shoes will bear a label identifying the animal from which the leather was taken. In this way, a Muslim would not accidentally purchase pigskin leather,[85] and a Hindu could avoid cow leather. Many Hindus who are vegetarians will not use any kind of leather.

Judaism forbids the wearing of shoes made with leather on Yom Kippur, Tisha B'Av, and during mourning.[86]

Jainism prohibits the use of leather because it is obtained by killing animals.

See also

- 1966 anti-cow slaughter agitation

- Ahir

- Apis

- Bat (goddess)

- Bull (mythology)

- Bull of Heaven

- Etiquette of Indian dining

- Food and drink prohibitions

- Gangotri (cow)

- Golden calf

- Kamadhenu

- Khnum

- Minotaur

- Nandi (bull)

- Naqada III

- Panchamrita

- Red heifer

- Sacred bull

- Shambo

- Táin Bó Cúailnge

- Tarvos Trigaranus

- Zebu, the common breed of cow from India

Notes

References

- ↑ LTD, Lankacom PVT. "The Island". www.island.lk. Retrieved 2018-08-24.

- ↑ "The states where cow slaughter is legal in India". The Indian Express. 2015-10-08. Retrieved 2018-08-24.

- 1 2 3 Animals and Society: An Introduction to Human-animal Studies, Margo DeMello, p.314, Columbia University Press, 2012

- ↑ Jha, Dwijendra Narayan. The Myth of the Holy Cow. London/New York: Verso 2002

- ↑ Achaya, K. T. (2002). A Historical Dictionary of Indian Food. Oxford University Press. pp. 16–17. ISBN 0-19-565868-X.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Marvin Harris (1990), India's sacred cow, Anthropology: contemporary perspectives, 6th edition, Editors: Phillip Whitten & David Hunter, Scott Foresman, ISBN 0-673-52074-9, pages 201–204

- ↑ Christopher Chapple (1993). Nonviolence to Animals, Earth, and Self in Asian Traditions. State University of New York Press. pp. 10–18. ISBN 978-0-7914-1497-2.

- ↑ Tähtinen, Unto (1976), Ahimsa. Non-Violence in Indian Tradition, London: Rider, ISBN 978-0091233402, pp. 1-6, 107-109.

- 1 2 3 4 Lisa Kemmerer (2011). Animals and World Religions. Oxford University Press. pp. 59–68 (Hinduism), pp. 100–110 (Buddhism). ISBN 978-0-19-979076-0.

- ↑ V.M. Apte, Religion and Philosophy, The Vedic Age

- ↑ Krishna, Nanditha (2014), Sacred Animals of India, Penguin Books Limited, pp. 80, 101–108, ISBN 978-81-8475-182-6

- ↑ Krishna, Nanditha (2014), Sacred Animals of India, Penguin Books Limited, pp. 15, 33, ISBN 978-81-8475-182-6

- ↑ ऋग्वेद: सूक्तं १०.८७, Wikisource, Quote: "यः पौरुषेयेण क्रविषा समङ्क्ते यो अश्व्येन पशुना यातुधानः । यो अघ्न्याया भरति क्षीरमग्ने तेषां शीर्षाणि हरसापि वृश्च ॥१६॥"

- ↑ Ludwig Alsdorf (2010). The History of Vegetarianism and Cow-Veneration in India. Routledge. pp. 32–44 with footnotes. ISBN 978-1-135-16641-0.

- ↑ John R. McLane (2015). Indian Nationalism and the Early Congress. Princeton University Press. pp. 271–280 with footnotes. ISBN 978-1-4008-7023-3.

- 1 2 3 Alsdorf, Ludwig (2010). The History of Vegetarianism and Cow-Veneration in India. Routledge. pp. 2–4. ISBN 978-11351-66-410.

- ↑ Christopher John Fuller (2004). The Camphor Flame: Popular Hinduism and Society in India. Princeton University Press. pp. 46, 83–85, 141. ISBN 0-691-12048-X.

- ↑ (Achaya 2002, p. 55)

- ↑ "milking of the Earth". Texts.00.gs. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ↑ Biardeau, Madeleine (1993). "Kamadhenu: The Mythical Cow, Symbol of Prosperity". In Yves Bonnefoy. Asian mythologies. University of Chicago Press. p. 99. ISBN 0-226-06456-5.

- ↑ Smith, Frederick M. (2006). The self possessed: Deity and spirit possession in South Asian literature and civilization. Columbia University Press. pp. 404, pp. 402–3 (Plates 5 and 6 for the two representations of Kamadhenu). ISBN 978-0-231-13748-5.

- ↑ R. Venugopalam (2003). "Animal Deities". Rituals and Culture of India. B. Jain Publishers. pp. 119–120. ISBN 81-8056-373-1.

- ↑ Raminder Kaur; William Mazzarella (2009). Censorship in South Asia: Cultural Regulation from Sedition to Seduction. Indiana University Press. pp. 36–38. ISBN 0-253-22093-9.

- ↑ W. and R. Chambers (1891). Chambers's Encyclopaedia: A Dictionary of Universal Knowledge for the People. 8. p. 719.

- ↑ Banu, Zenab. "Appendix IV". Politics of Communalism. pp. 175–193.

- ↑ "Report of the National Commission on Cattle – Chapter II (10 A. Cow Protection in pre-Independence India)". DAHD. Retrieved 2013-11-08.

- 1 2 "Compilation of Gandhi's views on Cow Protection". Dahd.nic.in. 7 July 1927. Archived from the original on 25 November 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ↑ Susan J. Armstrong; Richard G. Botzler (2016). The Animal Ethics Reader. Taylor & Francis. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-317-42197-9.

- ↑ Paul Dundas (2003). The Jains. Routledge. pp. 160–162. ISBN 978-04152-66-055.

- 1 2 Lisa Kemmerer; Anthony J. Nocella (2011). Call to Compassion: Reflections on Animal Advocacy from the World's Religions. New York: Booklight. pp. 57–60. ISBN 978-1-59056-281-9.

- ↑ Christopher Chapple (2002). Jainism and ecology: nonviolence in the web of life. Harvard Divinity School. pp. 7–14. ISBN 978-0-945454-33-5.

- 1 2 Lisa Kemmerer (2011). Animals and World Religions. Oxford University Press. pp. 100–101, 110. ISBN 978-0-19-979076-0.

- 1 2 McFarlane, Stewart (2001), Peter Harvey, ed., Buddhism, Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 187–191, ISBN 978-1-4411-4726-4

- ↑ Harvey, Peter (2013). An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practices (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 83, 273–274. ISBN 978-05216-767-48.

- ↑ Thich Nhat Hanh (2015). The Heart of the Buddha's Teaching: Transforming Suffering into Peace, Joy, and Liberation. Potter. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-101-90573-9.

- ↑ Martine Batchelor (2014). The Spirit of the Buddha. Yale University Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-300-17500-4. ; Quote: These five trades, O monks, should not be taken up by a lay follower: trading with weapons, trading in living beings, trading in meat, trading in intoxicants, trading in poison."

- 1 2 H. Saddhatissa (2013). The Sutta-Nipata: A New Translation from the Pali Canon. Routledge. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-136-77293-1.

- ↑ R Ganguli (1931), Cattle and Cattle-rearing in Ancient India, Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Vol. 12, No. 3 (1931), pp. 216–230

- ↑ How Brahmins Lived by the Dharma, Early Buddhist texts, translations, and parallels, Sutta Central

- 1 2 Richard Gombrich (2012). Buddhist Precept & Practice. Routledge. pp. 303–307. ISBN 978-1-136-15623-6.

- ↑ Matthew J. Walton (2016). Buddhism, Politics and Political Thought in Myanmar. Cambridge University Press. pp. 34–35. ISBN 978-1-107-15569-5.

- 1 2 Clark, P. 13 Zoroastrianism

- ↑ Vogelsang, P. 63 The Afghans

- 1 2 P. 72 Some Aspects of Ancient Indian Culture by D. R. Bhandarkar

- ↑ Carmichael, Calum (2012). The Book of Numbers: A Critique of Genesis. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. pp. 103–121. ISBN 9780300179187.

- ↑ "Apocalypse Cow". The New York Times. March 30, 1997. Retrieved December 21, 2013.

- ↑ Hersh, June (2011). The Kosher Carnivore: The Ultimate Meat and Poultry Cookbook. Macmillan Publishers. pp. 19–21. ISBN 9781429987783.

- ↑ Goldman, Ari L. (2007). Being Jewish: The Spiritual and Cultural Practice of Judaism Today. Simon & Schuster. p. 234. ISBN 9781416536024.

- ↑ "Rabbinic Statement". Jewish Veg. Retrieved 2017-10-16.

- ↑ Nussbaum, Martha Craven. The Clash Within: Democracy, Religious Violence, and India's Future. p. 224.

- ↑ Diane Morgan (2010). "Essential Islam: A Comprehensive Guide to Belief and Practice". ABC-CLIO. p. 27. ISBN 9780313360251.

- ↑ Thomas Hughes (1995) [first published in 1885]. "Dictionary of Islam". Asian Educational Services. p. 364. ISBN 9788120606722.

- ↑ Avinoam Shalem (2013). "Constructing the Image of Muhammad in Europe". Walter de Gruyter. p. 127. ISBN 9783110300864.

- ↑ Rosalind Ward Gwynne (2014). "Logic, Rhetoric and Legal Reasoning in the Qur'an: God's Arguments". Routledge. p. 38. ISBN 9781134344994.

- ↑ Mahmoud M. Ayoub (1984). "The Qur'an and Its Interpreters, Volume 1". SUNY Press. p. 117. ISBN 9780873957274.

- ↑ Analysis and summary of Herodotus, with a synchronistical table of principal events; tables of weights, measures, money, and distances; an outline of the history and geography; and the dates completed from Gaisford, Baehr, etc., by J. Talboys Wheeler, p. 57

- ↑ "ANNEX II (8)". Dahd.nic.in. 30 August 1976. Archived from the original on 9 November 2014. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ↑ Tadeusz, Margul (1968). "Present Day Worship Of The Cow In India". ATLA Religion Database with ATLASerials. Numen. 15 (1): 63–80.

- ↑ Agoramoorthy, Govindasamy (2012). "The significance of cows in Indian society between sacredness and economy" (PDF). Anthropological Notebooks. pp. 8–9. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ↑ 4 held for violating ban on cow slaughter, The Himalayan Times

- ↑ "Injured cow in Nepal is serious matter". Yahoo! News. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- ↑ Jolly, Joanna (24 November 2009). "Devotees flock to Nepal animal sacrifice festival". BBC. Retrieved 24 November 2009.

- ↑ "Over 20,000 buffaloes slaughtered in Gadhimai festival". NepalNews.com. 25 November 2009. Retrieved 25 November 2009.

- ↑ Ram Chandra, Shah. "Gadhimai Temple Trust Chairman, Mr Ram Chandra Shah, on the decision to stop holding animal sacrifices during the Gadhimai festival:" (PDF). Humane Society International. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- 1 2 Devendra,, C.; Devendra, C.; Thomas, D.; Jabbar, M.A.; Kudo, H.; Thomas, D.; Jabbar, M.A.; Kudo, H. Improvement of livestock production in crop-animal systems in rainfed agro-ecological zones of South-East Asia. ILRI. p. 33.

- ↑ Gesteland, Richard R.; Georg F. Seyk (2002). Marketing across cultures in Asia. Copenhagen Business School Press DK. p. 156. ISBN 978-87-630-0094-9.

- ↑ U Khin Win (1991). A century of rice improvement in Burma. International Rice Research Institute. pp. 27, 44. ISBN 978-971-22-0024-3.

- ↑ Meyer, Arthur L.; Jon M. Vann (2003). The Appetizer Atlas: A World of Small Bites. John Wiley and Sons. p. 276. ISBN 978-0-471-41102-4.

- ↑ Simoons, Frederick J. (1994). Eat not this flesh: food avoidances from prehistory to the present. Univ of Wisconsin Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-299-14254-4.

- ↑ Spiro, Melford (1982). Buddhism and society: a great tradition and its Burmese vicissitudes. University of California Press. p. 46. ISBN 0-520-04672-2.

- ↑ Hardiman, John Percy (1900). Gazetteer of Upper Burma and the Shan States. 2. Government of Burma. pp. 93–94.

- 1 2 Charney, Michael (2007). "Demographic Growth, Agricultural Expansion and Livestock in the Lower Chindwin in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries". In Greg Bankoff, P. Boomgaard. A history of natural resources in Asia: the wealth of nature. MacMillan. pp. 236–40. ISBN 978-1-4039-7736-6.

- ↑ King, Winston L. (2001). In the hope of Nibbana: the ethics of Theravada Buddhism. 2. Pariyatti. p. 295. ISBN 978-1-928706-08-3.

- ↑ Fervour that ended in a fatal fire

- ↑ Katz, Paul R. (2008). Divine justice: religion and the development of Chinese legal culture. Academia Sinica on East Asia. Taylor & Francis US. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-415-44345-6.

- ↑ Classic of Rites

- ↑ 民間私營養牛業(附私營牧駝業) Archived 13 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ http://www.eywedu.com/Huizuyanjiu/hzyj2007/hzyj20070208.html

- ↑ Hutton, Wendy (2007). Singapore food. Marshall Cavendish. p. 144. ISBN 978-981-261-321-9.

- 1 2 3 4 Sterckx, Roel (2005). Of tripod and palate: food, politics and religion in traditional China – Chapter 11, The Beef Taboo and the Sacrificial Structure of Late Imperial Chinese Society, Vincent Goossaert. Macmillan. pp. 237–248. ISBN 978-1-4039-6337-6.

- ↑ Elverskog, Johan (2010). Buddhism and Islam on the Silk Road. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-8122-4237-9.

- ↑ 慈雲閣——看靈牛遊地獄 Archived 5 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Cwiertka, Katarzyna Joanna (2006). Modern Japanese cuisine: food, power, and national identity. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-298-0.

- 1 2 3 Lien, Marianne E.; Brigitte Nerlich (2004). The politics of food. Berg. pp. 125–127. ISBN 978-1-85973-853-5.

- ↑ "Global Business Strategies: Text and Cases" by U.C. Mathur, p.219

- ↑ "Wearing Shoes – Mourning Observances of Shiva and Sheloshim". Chabad.org. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

Bibliography

- Achaya, K. T. (2002), A Historical Dictionary of Indian Food, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-565868-X

- Sethna, K. D. (1980), The Problem of Aryan Origins (published 1992), ISBN 81-85179-67-0

- Shaffer, Jim G. (1995), "Cultural tradition and Palaeoethnicity in South Asian Archaeology", in Erdosy, George, The Indo-Aryans of Ancient South Asia, ISBN 3-11-014447-6

- Shaffer, Jim G. (1999), "Migration, Philology and South Asian Archaeology", in Bronkhorst, Johannes; Deshpande, Madhav, The Indo-Aryans of Ancient South Asia, ISBN 1-888789-04-2

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sacred cows. |

- Sacredness of native Cow breeds of India

- Save Mother Cow

- Photo essay examining the changing place of the Holy Cow in India

- Cows in Hinduism

- Sacredness of cow in Rigveda and the words of Gandhi, from Hinduism Today

- Gau-Mata and her secret meanings

- Why Hindus Consider Cow as Sacred Mother

- Milk in a vegetarian diet, from Sanatan Society, a Hindu association

- Sacred No Longer: The suffering of cattle for the Indian leather trade, from Advocates for Animals

- Rise In Animal Slaughter in India, by Tony Mathews

- "Pamela Anderson Lee Exposes Animal Cruelty in the International Leather Trade", from PETA

- Deonar Abattoir: Report on the Failure of Government and of Management to Meet Humane, Hygiene, Religious, and Legal Standards for Slaughter and Animal Handling, from PETA

- People for Animals, an Indian animal rights organisation

- India cow report, by Balabhadra das, ISCOWP

- Hinduism: Why do Hindus regard the cow as sacred?

- Jainism & Status of Cows in India:- By Mr. Anil Kumar Jain

- Elephant who cried after being freed from abusive owners will remain free

.jpg)