Castra Albana

| Castra Albana | |

|---|---|

|

The central arch of the porta Praetoria of the castra | |

| Founded during the reign of | Septimius Severus |

| Place in the Roman world | |

| Province | Italia |

| Structure | |

| — stone structure — | |

| Size and area | 437 m × 239 m (9.5 ha) |

| Stationed military units | |

| — Legions — | |

| Legio II Parthica | |

| Location | |

| Town | Albano Laziale |

| County | Roma |

| State | Lazio |

| Country | Italy |

The Castra Albana [ˈkastra alˈbaːna] was a permanent legionary fortress of the Legio II Parthica, founded by the Emperor Septimius Severus (193-211) on the modern site of Albano Laziale. Today, the ruins of the structures inside the castra, such as the so-called Baths of Caracalla and the Amphitheatre represent one of the largest collections of Roman archaeological remains in Latium, outside of Rome.

History

The origin of the name

The fortress of Legio II Parthica was named Albana making reference to the legendary capital of the Latin League, Alba Longa, founded by Ascanius, the son of Aeneas, thirty years after the foundation of Lavinium, "Near a mountain and a lake, sitting in the space between the two[1] The most common location suggested for this ancient mothercity of Rome today is the south side of Lake Albano, between Colle dei Cappuccini in the comune of Albano Laziale and the Convent of St Mary ad Nives of Palazzolo in Rocca di Papa.[2]

Related names in the area included Lacus Albanus, Mons Albanus, aqua Albana (perhaps an aqueduct on the south side of the lake), the rivus Albanus (probably the modern marana delle Pietrare near Marino) and "Albani Longani Bovillenses", the official name of the inhabitants of the municipium of Bovillae (located on the Appian Way near the modern village of Frattocchie),[3] The adjective Albanus was also used as a poetic synonym for Romanus.

It is no coincidence, therefore, that the legio II Parthica came to be known as legio Albana and its legionaries as Albani,[4] even though the whole legion did not remain at the Castra Albana, but had other encampments in Mesopotamia.

Republican Era to Domitian

In the Republican period, the area of the later castra was occupied only by some fortifications which were razed to the ground in the time of Severus during the construction of the encampment; remains have been found at various points in central Albano Laziale. Several suburban villas of Roman nobiles have been found in the general area, including the villas of Publius Clodius Pulcher (near Ercolano in Castel Gandolfo),[5] and perhaps of Pompey the Great (in the Villa Doria)[6][7] and an anonymous villa discovered near the railway station.[8]

The great abundance of villas and farms in the area must result from the ease of direct communication with Rome thanks to the Appian Way, built in 312 BC by the Censor Appius Claudius Caecus to connect the city of Rome with Capua,[9] in Campania. In 293 BC the road was paved in saxum quadratum up to Bovillae.[9] Later it was extended to Benevento and then to the Greek port of Brindisi.[9]

In the eighteenth century, Giovanni Antonio Ricci suggested the existence of a municipium which he called "Alba Media" on the site of Albano.,[10] but this theory conflated the evidence from another localities of the same name: Alba Pompeia (modern Alba) and Alba Fucens. Ricci was thoroughly confuted in the following centuries,[11] and it is now established that until the time of Domitian, the stretch of the Appian Way between Bovillae and Aricia (modern Frattocchie in Marino and Ariccia) was completely free of buildings, as shown by Tacitus Histories 4.2 on the Year of the Four Emperors (69) and the final phase of the civil war between Vitellius and Vespasian, which states that the army of Vitellius was camped partially at Bovillae and partially at Aricia, indicating that there was nothing in between the two centres[12] which were themselves in decline.

Domitian, second son of Vespasian became Emperor in 81 and immediately dedicated himself to an ambitious project: the construction of an imposing Imperial villa in the Alban Hills to replace the villa previously used by various Emperors (dating to Tiberius), which is probably the same as the villa attributed to Pompey the Great and located in the Villa Doria, now a part of the imperial patrimony.[13] The new villa, the Villa of Domitian was a true palace, located inside the modern Villa Barberini, near Castel Gandolfo, in the extraterritorial zone of the Papal Palace of Castel Gandolfo,[14] on an estate containing a series of villas, already Imperial property for various reasons, with an area of 13 or 14 square kilometres, abutting Lake Albano and perhaps also Lake Nemi.[15] The villa was frequently used by Domitian, but it later fell into disuse, on account of the construction of the more famous Villa of Hadrian at Tivoli by Hadrian (117-136), who also began a policy of selling surplus Imperial property, including some of the villas on the edge of "Albanum Caesarum".[13]

Septimius Severus to Philip the Arab

The Villa of Domitian at Castel Gandolfo was probably garrisoned by a detachment of the Praetorian Guard when the Emperor was in residence,[16][17] although documents, archaeology, and epigraphy provide no explicit testimony of this residence.[18] The archaeologist Giuseppe Lugli has, moreover, confuted all attempts to move the date of the castra structure which is now visible in the historic centre of Albano back. These attempts included the aforementioned Giovanni Antonio Ricci, who dated the encampment to the Second Punic War (219 BC-202 BC),[19] the Jesuit priest Giuseppe Rocco Volpi who thought it dated to Augustus and Tocco who decided that it was the acropolis of Alba Longa.[18]

The date universally considered correct for the castra is starting in the reign of Septimius Severus (193-211), who came to the throne after the Year of the Five Emperors and a violent civil war and thought it best to temporarily dissolve the Praetorian Guard and bring the Legio II Parthica near Rome for his personal and political security.[20] This legion had been created in 197 for the (successful) campaign against Parthia which ended in 198 with the sack of Ctesiphon (near modern Baghdad, Iraq).

The site chosen for the foundation of the castra, which might seem unsuitable due to the steep slope of the terrain, was actually an excellent position with a panoramic view - ideal for the point of observation of the Ager Romanus which the camp was to be.[4]

An incident related to the castra occurred in the Principate of Caracalla (211-217), who came to power after assassinating his brother and co-emperor, Geta. This fratricide angered the Legio Parthica, which insisted that it had sworn fialty to both the sons of Septimius Severus and refused to accept Caracalla as sole emperor.[21] He went in person to Castra Albana and after a long meeting with the legionaries he convinced them to remain loyal, by promising to increase their stipend by fifty percent[22] and to improve the camp by having the imposing Baths of Caracalla erected.[4]

The documentary evidence shows the last trace of the legion's presence at Castra Albana in 226 AD, although the legion had been active in campaigns abroad from 208-11 AD (in Britain) and afterwards under Caracalla against the Germanic tribe of the Alamanni in 213. Next, the legion was again sent to Parthia and their commander Macrinus was responsible for Caracalla's murder in that region in 217. In the following year, however, the II Parthica, stationed in Apamea (Syria), abandoned Macrinus and sided with Elagabalus; the Second supported Elagabalus' rise to purple, defeating Macrinus in the Battle of Antioch.

The legion is mentioned in the ancient literary sources again in the 3rd century in the reign of Alexander Severus (222-235), Maximinus Thrax (235-238), Philip the Arab (244-249).[23]

The construction of the Roman Amphitheatre of Albano Laziale can be dated to the middle of this century and could mark the end of the period of highest prosperity for the Legio II Parthica although it may no longer have been there.[24]

Decline of the castra after Constantine

Legio II Parthica is mentioned for the last time at the beginning of the 5th century, near the camp of Cepha (modern Hasankeyf, Turkey). Thereafter it disappears from history. But even at the beginning of the 4th century, the legion had abandoned Castra Albana to settle in the strategic city of Bezabde (modern Cizre, Turkey) on the river Tigris, at the ever troubled eastern border of the Roman Empire.

In the Liber Pontificalis it is stated that the Emperor Constantine I (306-337) founded the Cathedral of San Giovanni Battista at Albano Laziale during the pontificate of Pope Silvester I (314-335), providing the cathedral with decorations and substantial property in the Alban Hills,[25] including the sceneca deserta vel domos civitatis (the abandoned tents or the houses of the city).[26] It can thus be deduced that modern Albano Laziale was born on the remains of the castra, which explains the fact that the historic centre of Albano Laziale is literally founded atop the ancient encampment, whose remains are generally found only 50-200 centimetres below the modern ground level.

Description

Archaeological remains

Circuit wall

Like all Roman castra, the Castra Albana followed a strict civic design, forming a large fortified rectangle with four gates (praetoria, decumana, principalis sinistra and principalis dextra), with rounded corners reinforced by circular turrets (an unusual feature, but similar to the castra of Hadrian's Wall in Britain).[27] The construction technique is Opus quadratum - one of its latest appearances in the Ager Romanus[28] (it was supplanted by Opus latericium). The construction material is Peperino, extracted in situ from the volcanic soil on which the castra was built, which would have saved time and money.[29] The construction was made difficult by the position of the encampment on an 11 degree slope, a situation which required a technical solution - a differing placement of blocks depending on the slope at different points on the wall.[30] The perimeter of the wall circuit is 1334 metres; the northwest side measures 434 metres, while the parallel southeast side measures 437 metres and of the short sides, the northeast measures 224 metres, while the southwest measures 239 metres.[31] The total area, therefore, is around 95,000 square metres.

Northeast side

At the end of the northeastern side of the circuit wall, probable traces of a circular turret were found within the building of the Society of the Sacred Heart near San Paolo until the building's complete destruction by Allied aerial bombardment during the Second World War. Today, this is the site of an episcopal seminary and a centre for vocational training. The circular room inside the convent, described before the war, had a diameter of 3.63 metres and was covered by a low dome of very poor workmanship, probably a modern repair.

Going along the Roman wall, it is better preserved stretch for about fifty metres, because it serves as the boundary wall between the property of the episcopal seminary and the Missionaries of the Precious Blood, which govern the church of San Paulo.[32] This stretch was built with very great care, because it had to function as the external retaining wall as well, to a depth of four metres.[32] For this reason it is also very monumental and robust.[33] No trace remains of the porta decumana which must have been around the middle of this stretch and was probably accessed by a staircase of a ramp.[32]

Past the Via San Francesco d'Assisi, on which the Medieval gate of the Cappuchins opened until the second half of the Nineteenth century,[32] the wall follows the Via Tacito, on the property of the Daughters of Immaculate Mary. At the corner of their property, the rounded corner of the ancient wall is still visible, but the circular turret is not, though the need for the wall to bear its weight is reflected in the stronger structure of the wall.[34]

Southeast side

This is the best preserved side, including the remains of a rectangular guard tower and of the porta principalis sinistra as well as a long stretch of wall, preserved for 142 metres on the Via Castro Partico.[33]

Turning onto the Via Castro Partico, still on the property of the Daughters of Immaculate Mary, sixty metres from the rounded corner,[34] the wall contains a rectangular guard tower, currently put to use as a farmhouse. The internal space measures 5.90 x 3.85 metres and the walls are 0.90 metres thick (except the exterior wall which is inexplicably only 0.59 metres thick). The entrance is still that used in antiquity, facing the inside of the castra and is 1.78 metres wide.[34] The wall then continues on the property of the modern Liceo classico statale Ugo Foscolo and around two hundred metres further on,[35] the remains of the porta principalis sinistra are found - the only one of the two portae principales which can still be seen.

The gate, considered one of the most beautiful remnants of the castra by the archaeologist Giuseppe Lugli,[35] consisted of a single archway where the ashlar blocks meter with the horizontal ones of the wall. It is 3.85 metres wide and no traces of guard towers have been found on either side.[35] Along from the gate, next to the old civic hospital building (now the municipal police station) traces of the wall can no longer be made out.[35] Nor do any traces remain of the rounded corner fortified with a circular tower, which must have been located at the end of the modern Via San Francesco d'Assisi.

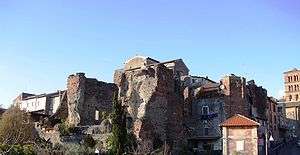

Southwest side

Some remains of the wall on this side were found in 1913, during the construction of the modern piazza Giosuè Carducci (Italian pronunciation: [dʒoˈzwɛ karˈduttʃi]), and more have been incorporated into the foundations of modern houses.[36] The most substantial remains on this side, however, are those of the porta praetoria, right in front of the Palazzo Savelli. Located at the midpoint of the wall, the gate was incorporated into a later building, preventing the "liberation" of Roman monument, until the devastating Anglo-American aerial bombardment of 1 February 1944.[37] The central archway measure around 3 x 5 metres with a height of 14 metres[36][37] while the two side archways were a little over 1 x 5 metres. The two side chambers each measure 5.40 x 5 metres.[36][37]

Further to the north, the wall is visible for stretches on local land, facing Via San Pancrazio. On the same street, the well-conserved remains of a circular guard tower can be accessed, 3.40 metres below the modern ground level of the Via Alcide de Gasperi.[27] The construction poses a problem: the vault of the single room is only 1.60 metres above the level of the intervallum and even allowing for the existence of a second story (per Giuseppe Lugli), the tower would not have reached a plausible height to be a guard tower.[27] The conclusion is that this was a special construction, perhaps only for symmetry with the now-destroyed tower of the southeast corner.[27] At any rate, it has a diameter of 1.2 metres, a height of 2.10 metres and its walls are 0.90 metres thick.[27]

Northwest side

The greater part of the wall of this side, after the aforementioned circular tower is buried under modern houses. Presumably, the porta principalis dextra was located on the location of a courtyard off the Via Don Giovanni Minzoni.[38] The wall then proceeded along the line of the facades of the houses on the south side of the modern Via San Gaspare del Bufalo, passing the sixteenth century Trident of the streets, and ending at the modern piazza San Paolo, where some remains were found during some hydraulic work in 1904, arranged in horizontal layers to deal with the steep slope of the terrain.[38] There the wall meets the corner described above in the section on the northeast side.

Road network

The road system of a Roman castra was extremely organised and regular and consisted of a basic system of two perpendicular main streets with smaller streets running parallel to them. The main streets were the via praetoria (Headquarters Street) and the via principalis (Parade Ground Street). The former ran the whole length of the castra, connecting the porta praetoria (Headquarters Gate) with the porta decumana (Tenth Gate), passing through the praetorium (Headquarters), while the via principalis crossed the camp in the other direction, connecting the two portae principales (Parade Ground Gates), distinguished as sinistra (Left) and dextra (Right).

At Albano, stretches of both of these streets have been excavated - only a short stretch of the via praetoria, near the homonymous gate on the modern Alcide De Gasperi Street, while two stretches of the via principalis survive: one near the porta principalis sinistra and the other on San Francesco d'Assisi Street, which was discovered during the archaeological excavations of 1915-1916, 1.10 metres below the modern ground level. This stretch is very important because so much of crepido (sidewalk) facing the gutter was found.[39] In the 1980s some excavations carried out by the Museo civico of Albano Laziale and the Ramacci company on the site of a demolished seminary on Castro Pretorio Street discovered the intersection between the via principalis and one of roads running parallel to the via praetoria. This street had been blocked with peperino pilasters in the Medieval period - a sign of the contraction of the inhabited area at the time.[40]

It has also been possible to identify the location of another street within the castra: the via quintana (Fifth Street), which connected the rectangular guard towers. Given the location of one of these towers in Castro Partico Street, the remains of a perpendicular street were found on the part of the via principalis in San Francesco d'Asisi Street, a little past Liceo classico statale Ugo Foscolo.

Pretty abundant remains of the circumductio, the street which encircled the walls on the outside, and of the intervallum, the street which ran around the inside of the walls.

With respect to the circumductio, portions have been discovered along the north east side under the modern Tacito Street;[34] along the southwest side near the aforementioned rectangular guard tower on Castro Partico Street,[34] 1.5 metres below ground level at a spot 18 metres from the porta principalis sinistra, and a little further along in the public carpark; along the southeast side 0.5 metres below San Pancrazio Street;[27] and along the northwest side in the piazza della Rotonda, on San Gaspare del Bufalo Street and in the piazza San Paolo.[41] A terrace from the intervallum remains on the northeast side, as well as a good stretch near the porta praetoria and at the end of Aurelio Saffi Street on the southeast side, and also some bits on the northwest side.[38]

Outside the castra, under the modern Giacomo Matteotti Road, many remains of the foundations of the Appian Way have been found.[42] There are also some remains at the end of Risorgimento Ave[43] and Europe Ave.[42]

The porta praetoria is six metres above the Appian Way and twenty metres away from it.[43] It is unknown how this gap was bridged - presumably there was a stairway for pedestrians as well as one or two paths for vehicular traffic which descended from the gate to the regina viarum (Queen of Roads). Part of such a stairway, running in a north-south direction, was thought to have been discovered in the 1980s under Palazzo Savelli, during the construction of public toilets.[43]

Internal buildings

The "Round Building"

The "Round Building", today known as the Santa Maria della Rotonda is the best preserved Roman structure in Albano. The circular interior has a circumference of 49.10 metres[44] and mimicks the Pantheon in Rome on a reduced scale. However, the building is not contemporary with the castra, but earlier, dating to the time of Domitian. It was probably a nymphaeum of the Villa of Domitian.[45][46] Later it was restored and incorporated into the Severan complex and used as a public baths or cult site. The first theory would explain the paviment of white and black mosaic tesserae with mythological figures, today located in the portico of the church.[47] The second theory is supported by a peperino pagan altar and by some tombs found during archaeological excavations in 1935-38.[48] After the Severan period, the structure was used as a granary or cult building, before conversion to a Christian building around the eighth century.[49]

The "thermae parvae"

Some individual ruins in the ground near the piazza della Rotonda and Don Giovanni Minzoni Street have been called "thermae parvae" (Small Baths) in some reconstructions of the castra, to distinguish them from the "thermae magnae" (Large Baths), the Baths of Caracalla.[50] These remains are under some houses on Don Giovanni Minzoni Street and are made up of two corridors, about a metre deep, one 2.70 metres long and the other 3.29 metres, with a series of niches along the walls. The construction was entirely carried out in opus reticulatum using peperino in the Severan period - it was the last building to use this technique in the Ager Romanus.[51] These corridors are probably the cryptoportici of the bath, connected to other bathing rooms located in Piazza della Rotonda,[52] near the modern Palazzo Vescovile.

Soldiers' lodgings

Not much remains of the buildings within the castra - some terraces, probably part of a barracks or soldiers' lodgings, have been found in the retentura (the part of the castra located between the praetorium and the porta decumana), inside the property of the episcopal seminary and the property of the Daughters of Immaculate Mary on San Fracesco d'Assisi Street. These ruins consist of five walls of the substructure arranged on different levels. On the second level, traces of a partition wall were found, which created rooms about 6 metres wide.[53]

During the archaeological excavations of 1915-1916, they found walls of 4.50 x 4.50 metre rooms in various constructive techniques on top of older walls dating back to the 1st century BC, all along San Francesco d'Assisi Street from the rectangular tower to the porta principalis sinistra.[39]

Further, indecipherable patterns of parallel walls were found in 1914 near the northwest side, in the Piazza della Rotonda. They are not aligned with the grid of the castra and a bulla from the time of Hadrian, which suggests that these buildings predated the castra and were razed to the ground during its construction.[39] "An intricate pattern of walls"[41] was found under the Piazza della Rotonda, where the excavators of 1915-1916 found the remains of the rooms mixed with blocks of peperino fallen from the nearby wall of the northwest side. Other rooms were identified in the Piazza San Paolo from the same period.[41] In general, the lodgings were built in opus latericium, interspersed with blocks of peperino from the end of the second century.[41] In the 1980s, further remains of lodgings were identified, as well as a building with a portico on Castro Pretorio Street.

"The Cisternoni"

The very large cistern of the castra is found under the property of the episcopal seminary, with access from the piazza San Paolo and San Francesco d'Assisi Street. It is known to the Albanese as the Cisternoni (giant cisterns). The long sides measure 45.50 and 47.90 metres, while the short sides are 29.62 and 31.90 metres long, for a surface area of 1436.50 square metres and a capacity of 10,132 cubic metres of water.[40] The structure, with five aisles, was carved into the bedrock as far as possible to a depth of between three and four metres; the height of the vaults is around 6.5 metres, with significant variation.[54] On account of some ornamental elements discovered in 1830 and 1884 it is believed that at least the front of the monumental structure was ornate.[40] Until the 1920s only a single supply tunnel of the cistern was known, which is located on the northeastern side. But the archaeologist Giuseppe Lugli discovered a second, more ancient tunnel on the same side, which served the cistern through a complex system until it broke.[40] The water came to the Cisternoni from the Malafitto and Palazzolo springs, near Lake Albano. The cistern was still used by the Comune of Albano in 1884, but for hygiene reasons it was restricted to use for irrigation in 1912.[54]

Other cisterns, drains, and sewers

One particular cistern of an elongated shape (around 30 metres long and 4.16 metres wide)[39] with a barrel vault was discovered under Aurelio Saffi Street. It was probably part of a larger, no longer identifiable cistern.[40] A decent stretch of the supply tunnel of the cistern survives as well, pointing to the northeast.[39]

The sewage network of the castra must have been extensive and would have followed the slope of the hill, discharging into the main sewer running under the intervallum in Alcide De Gasperi Street. The first stretch of this main sewer - 0.9 metres wide - was discovered in 1915-6 at the intersection of Alcide De Gasperi Street and San Francesco d'Assisi Street.

"Praetorium"

Unfortunately, nothing can be discerned of the praetorium, the main building of the castra. All that is known is that, since it must have been found at the intersection of the via praetoria and the via principalis, it must be under a block of houses at the end of Aurelio Saffi Street.[44]

Roman Amphitheatre

The Roman Amphitheatre of Albano Laziale is one of the most unusual monuments of the castra. For a long time it was believed to have been part of the Villa of Domitian, but the archaeologist Giuseppe Lugli dated it to the middle of the third century AD - well after the construction of the castra and even of the baths.[24] The building, with a maximum length of 113 metres,[55] could fit 14,850 seats and contain up to 16,000 people.[56] Today, the southern half of the amphitheatre is visible, while the northern part is buried under the retaining walls of San Francesco d'Assisi St and Anfiteatro Romano Street. Among the other remains, partially carved from the living rock and partially built of opus quadratum, are the pulvinar (the Imperial box),[57] some very unusual and "bizarre"[58] substructural archways, and vomitoria (access corridors).[55][59]

With respect to the wider complex, remains have been found of a paved street which probably followed the course of the modernday Anfiteatro Romano Street to link up with the Appian Way and followed the modern "galleria di sopra" in the other direction to the Villa of Domitian.[58] Future excavations might also clarify whether a connection with the porta decumana of the castra also existed.

Baths of Caracalla

The Baths of Caracalla or of Cellomaio are even today the most conspicuous evidence of the castra’s period of greatest splendour. Built by the Emperor Caracalla for the use of the legion in the period after the construction of the castra but before the construction of the amphitheatre, they later contained an entire Medieval neighbourhood. The best conserved part of the baths is a rectangular hall, 37 x 12 metres which is home to the Church of San Pietro.[60]

Underneath the sacristry of the church and near Cellomaio Street, a black and white mosaic floor from the baths was found.[60] Other notable remains were found in the garden of the Sisters of Jesus and Mary, which is probably planted over the hypocaust system which was used to heat the water.[60]

The building structure is made up of a core of peperino gravel cement, broken up by stretches of brickwork and faced with mattone bricks.[60]

Necropolis of Selvotta

The first discoveries near Selvotta, a place on the borders between Albano Laziale and Ariccia, were made in 1866 by a farmer called Lorenzo Fortunato and were analysed by the young Russian archaeologist Nicola Wendt.[61] The German archaeologist Wilhelm Henzen was the first to suggest that the frequent references to the Legio II Parthica found in the inscriptions discovered at Selvotta would have to indicate a necropolis of the legion, located a short distance from the castra.[61] A campaign of excavation and surveying in the area was carried out by Henzen, Hermann Dessau, and Rodolfo Lanciani at the end of the nineteenth century. Further campaigns were carried out by Giuseppe Lugli in 1908, 1910, 1913, 1945, and 1960-2 and by Maria Marchetti Longhi in 1916.[62]

In the 1960s about fifty tombs were discovered, of which two thirds had mortuary inscriptions. All were made in the same way, with the graves dug into the living rock and covered by a monolithic block of peperino in the form of a roof or a lid.[63] In the excavations of 1960-2 two unusual graves were found: a cippus grave with a broken column, characteristic of eastern tombs and a tomb with a cremation - the only one in the necropolis.[62] Wives and children were buried alongside the soldiers and there was no order to the arrangement of the tombs, although they were often grouped together.[62] From analysis of the grave inscriptions it is clear that the greater part of the soldiers bore the praenomen Aurelius and therefore it is deduced that they served in the time of the legion's greatest prosperity, during the reigns of Caracalla (211-217) and Elgabalus (218-222).[64] The women, on the other hand, have Italic names.[64]

Epigraphic documentation

There is little epigraphic testimony of the Legio II Parthica and a large amount of what there is was discovered around the necropolis in Selvotta. This large concentration of inscriptions (CIL XIV, 3367, CIL XIV, 3368, CIL XIV, 3369, CIL XIV, 3370, CIL XIV, 3371, CIL XIV, 3372, CIL XIV, 3373, CIL XIV, 3374, CIL XIV, 3375, CIL XIV, 3376, CIL XIV, 3377, CIL XIV, 3400 and many others)[62] permitted archaeologists from Wilhelm Henzen onwards to identify Castra Albana with the modern Albano Laziale for certain.[65]

Among the inscriptions referring to the legion and the castra, the most notable is CIL XIV, 2255,[4] while CIL XIV, 2257 is a prediction of the "eternal victory" of Elgabalus, in which the legion is called "Antoniana" after the full name of the reigning emperior. The same phenomenon is seen also in the reign of Septimius Severus or Alexander Severus, when the legion was called "Severiana" (CIL XIV, 2274, CIL XIV, 2276, CIL XIV, 2285, CIL XIV, 2290, CIL XIV, 2291, CIL XIV, 2293, CIL XIV, 2294, CIL XIV, 2296), and under Philip the Arab when the legion was called "Philippiana" (CIL XIV, 2258).[23]

In CIL XIV, 2255 a temple consecrated to Minerva is mentioned and a shrine to Jupiter appears in CIL XIV, 2253 and CIL XIV, 2254, while there is an altar dedicated to the Sun and the Moon in CIL XIV, 2256. The last epigraphic evidence regarding the Legio II Parthica at Albano is a series of little terracotta bricks which report the names of fome legionaries (CIL XIV, 2267, CIL XIV, 2268, CIL XIV, 2293) - the oldest of these dates to 226, the latest was reused in the foundations of Albano Cathedral in the reign of Constantine.[66]

Only three mentions of the Legio II Parthica have been found in Italia outside of the area of Albano. The first of these is a tile dedicated by the legion to the goddess (CIL XIV, 4090), which was found near the temple of Diana Aricina on Lake Nemi, in the nearby community of Nemi in 1884. The other two (CIL V, 865, CIL V, 866) were found near Aquileia in the Regio X Venetia et Histria. In the east, inscriptions relating to the legion are found in Mesopotamia and Syria.[23]

Notes

- ↑ "Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities 1.66". Retrieved 2009-07-21.

- ↑ Chiarucci, Pino. "La civiltà laziale e gli insediamenti albani in particolare": 39.

- ↑ Torquati, Girolamo. Studi storico-archeologici sulla città e sul territorio di Marino ordinati in tre volumi per Girolamo Torquati. p. vol. 1 cap. 20 p. 180. .

- 1 2 3 4 Lugli, Giuseppe (1969). Studi e ricerche su Albano archeologica 1914-1967, Second Edition. Albano Laziale. p. 265.

- ↑ Lugli, Giuseppe (1915). Le antiche ville dei Colli Albani prima dell'occupazione domizianea. Roma: Loescher. pp. 15–32.

- ↑ Lugli, Giuseppe (1915). Le antiche ville dei Colli Albani prima dell'occupazione domizianea. Roma: Loescher. pp. 33–47.

- ↑ Coarelli, Filippo (1981). Guide archeologhe Laterza - Dintorni di Roma, First Edition. Roma-Bari: Casa editrice Giuseppe Laterza & figli. p. 83.

- ↑ Lugli, Giuseppe (1915). Le antiche ville dei Colli Albani prima dell'occupazione domizianea. Roma: Loescher. pp. 54–55.

- 1 2 3 Coarelli, Filippo (1981). Guide archeologhe Laterza - Dintorni di Roma, First Edition. Roma-Bari: Casa editrice Giuseppe Laterza & figli. p. 10.

- ↑ Ricci, Giovanni Antonio (1787). Memorie Storiche dell' antichissima Città di Alba-Longa. Rome: Giovanni Zempel. p. 2.100.

- ↑ Emanuele Lucidi, part 1, chapter 3, page 23

- ↑ Emanuele Lucidi, part 1, chapter 3, page 29

- 1 2 Lugli, Giuseppe (1915). Le antiche ville dei Colli Albani prima dell'occupazione domizianea. Roma: Loescher. pp. 57–69.

- ↑ Lugli, Giuseppe (1920). La villa di Domiziano sui Colli Albani - parte II. Roma: Maglione & Strini. pp. 57–68.

- ↑ Lugli, Giuseppe (1918). La villa di Domiziano sui Colli Albani - parte I. Roma: Maglione & Strini. p. 6.

- ↑ Nibby, Antonio (1848). Analisi storico-topografico-antiquaria della carta de' dintorni di Roma, Second Edition. Roma: Tipografia delle Belle Arti. p. 1.95.

- ↑ Giorni, Francesco (1842). Storia di Albano. tip. Puccinelli. p. 68.

- 1 2 Lugli, Giuseppe (1919). "Castra Albana - parte I: un accampamento fortificato al XV miglio della via Appia". Ausonia. 9: 257.

- ↑ Ricci, Giovanni Antonio (1787). Memorie storiche dell'antichissima città di Alba Longa e dell'Albano moderno. Roma: Giovanni Zempel. p. 2.1.105.

- ↑ Lugli, Giuseppe (1919). "Castra Albana - parte I: un accampamento fortificato al XV miglio della via Appia". Ausonia. 9: 258.

- ↑ Lugli, Giuseppe (1965). "La legione II partica e il suo sepolcreto nell'Agro Albano". Gli Archeologi italiani in onore di Amedeo Maiuri: a cura del Centro studi Ciociaria. Napoli: Di Mauro. p. 222.

- ↑ Historia Augusta: Caracalla 2.7-8

- 1 2 3 Lugli, Giuseppe (1919). "Castra Albana - parte I: un accampamento fortificato al XV miglio della via Appia". Ausonia. 9: 263.

- 1 2 Lugli, Giuseppe (1921). "Castra Albana - parte II: l'anfiteatro dopo i recenti scavi". Ausonia. 10: 253.

- ↑ Liber Pontificalis 34.30

- ↑ Lugli, Giuseppe (1919). "Castra Albana - parte I: un accampamento fortificato al XV miglio della via Appia". Ausonia. 9: 265.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Lugli, Giuseppe (1919). "Castra Albana - parte I: un accampamento fortificato al XV miglio della via Appia". Ausonia. 9: 227.

- ↑ Lugli, Giuseppe (1919). "Castra Albana - parte I: un accampamento fortificato al XV miglio della via Appia". Ausonia. 9: 217.

- ↑ Lugli, Giuseppe (1919). "Castra Albana - parte I: un accampamento fortificato al XV miglio della via Appia". Ausonia. 9: 215.

- ↑ Lugli, Giuseppe (1919). "Castra Albana - parte I: un accampamento fortificato al XV miglio della via Appia". Ausonia. 9: 213.

- ↑ Lugli, Giuseppe (1919). "Castra Albana - parte I: un accampamento fortificato al XV miglio della via Appia". Ausonia. 9: 214.

- 1 2 3 4 Lugli, Giuseppe (1919). "Castra Albana - parte I: un accampamento fortificato al XV miglio della via Appia". Ausonia. 9: 220.

- 1 2 Chiarucci, Pino (1988). Albano Laziale, Second Edition. Albano Laziale: Museo Civico di Albano Laziale. p. 34.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lugli, Giuseppe (1919). "Castra Albana - parte I: un accampamento fortificato al XV miglio della via Appia". Ausonia. 9: 221.

- 1 2 3 4 Lugli, Giuseppe (1919). "Castra Albana - parte I: un accampamento fortificato al XV miglio della via Appia". Ausonia. 9: 222.

- 1 2 3 Lugli, Giuseppe (1919). "Castra Albana - parte I: un accampamento fortificato al XV miglio della via Appia". Ausonia. 9: 223–225.

- 1 2 3 Chiarucci, Pino (1988). Albano Laziale, Second Edition. Albano Laziale: Museo Civico di Albano Laziale. p. 31.

- 1 2 3 Lugli, Giuseppe (1919). "Castra Albana - parte I: un accampamento fortificato al XV miglio della via Appia". Ausonia. 9: 228.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lugli, Giuseppe (1919). "Castra Albana - parte I: un accampamento fortificato al XV miglio della via Appia". Ausonia. 9: 234.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Chiarucci, Pino (1988). Albano Laziale, Second Edition. Albano Laziale: Museo Civico di Albano Laziale. p. 35.

- 1 2 3 4 Lugli, Giuseppe (1919). "Castra Albana - parte I: un accampamento fortificato al XV miglio della via Appia". Ausonia. 9: 236.

- 1 2 Pino Chiarucci, Le origini del cristianesimo e le catacombe di San Senatore, p. 5.

- 1 2 3 Chiarucci, Pino (1988). Albano Laziale, Second Edition. Albano Laziale: Museo Civico di Albano Laziale. p. 38.

- 1 2 Lugli, Giuseppe (1919). "Castra Albana - parte I: un accampamento fortificato al XV miglio della via Appia". Ausonia. 9: 237.

- ↑ Lugli, Giuseppe (1919). "Castra Albana - parte I: un accampamento fortificato al XV miglio della via Appia". Ausonia. 9: 244–245.

- ↑ Galieti, Alberto (1948). Contributi alla storia della diocesi suburbicaria di Albano Laziale. p. 29.

- ↑ Coarelli, Filippo (1981). Guide archeologhe Laterza - Dintorni di Roma, First Edition. Roma-Bari: Casa editrice Giuseppe Laterza & figli. p. 88.

- ↑ Galieti, Alberto (1948). Contributi alla storia della diocesi suburbicaria di Albano Laziale. pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Galieti, Alberto (1948). Contributi alla storia della diocesi suburbicaria di Albano Laziale. p. 34.

- ↑ Pino Chiarucci, L'esercito romano, p. 52.

- ↑ Lugli, Giuseppe (1919). "Castra Albana - parte I: un accampamento fortificato al XV miglio della via Appia". Ausonia. 9: 233–234.

- ↑ Lugli, Giuseppe (1919). "Castra Albana - parte I: un accampamento fortificato al XV miglio della via Appia". Ausonia. 9: 235.

- ↑ Lugli, Giuseppe (1919). "Castra Albana - parte I: un accampamento fortificato al XV miglio della via Appia". Ausonia. 9: 230.

- 1 2 Lugli, Giuseppe (1919). "Castra Albana - parte I: un accampamento fortificato al XV miglio della via Appia". Ausonia. 9: 250–256. .

- 1 2 Coarelli, Filippo (1981). Guide archeologhe Laterza - Dintorni di Roma, First Edition. Roma-Bari: Casa editrice Giuseppe Laterza & figli. p. 90. .

- ↑ Lugli, Giuseppe (1921). "Castra Albana - parte II: l'anfiteatro dopo i recenti scavi". Ausonia. 10: 245–246. .

- ↑ Lugli, Giuseppe (1921). "Castra Albana - parte II: l'anfiteatro dopo i recenti scavi". Ausonia. 10: 242. .

- 1 2 Lugli, Giuseppe (1921). "Castra Albana - parte II: l'anfiteatro dopo i recenti scavi". Ausonia. 10: 228–229. .

- ↑ Lugli, Giuseppe (1921). "Castra Albana - parte II: l'anfiteatro dopo i recenti scavi". Ausonia. 10: 221–222. .

- 1 2 3 4 Chiarucci, Pino (1988). Albano Laziale, Second Edition. Albano Laziale: Museo Civico di Albano Laziale. p. 39. .

- 1 2 Lugli, Giuseppe (1965). "La Legione II Partica e il suo sepolcreto nell'agro Albano". Gli archeologi italiani in onore di Amedeo Maiuri. Napoli: Di Mauro Editore. pp. 1–2.

- 1 2 3 4 Lugli, Giuseppe (1965). "La Legione II Partica e il suo sepolcreto nell'agro Albano". Gli archeologi italiani in onore di Amedeo Maiuri. Napoli: Di Mauro Editore. pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Lugli, Giuseppe (1965). "La Legione II Partica e il suo sepolcreto nell'agro Albano". Gli archeologi italiani in onore di Amedeo Maiuri. Napoli: Di Mauro Editore. p. 5.

- 1 2 Lugli, Giuseppe (1965). "La Legione II Partica e il suo sepolcreto nell'agro Albano". Gli archeologi italiani in onore di Amedeo Maiuri. Napoli: Di Mauro Editore. p. 8.

- ↑ Lugli, Giuseppe (1919). "Castra Albana - parte I: un accampamento fortificato al XV miglio della via Appia". Ausonia. 9: 259. .

- ↑ Lugli, Giuseppe (1919). "Castra Albana - parte I: un accampamento fortificato al XV miglio della via Appia". Ausonia. 9: 264. .