''Cassini'' retirement

.jpg)

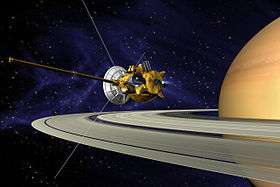

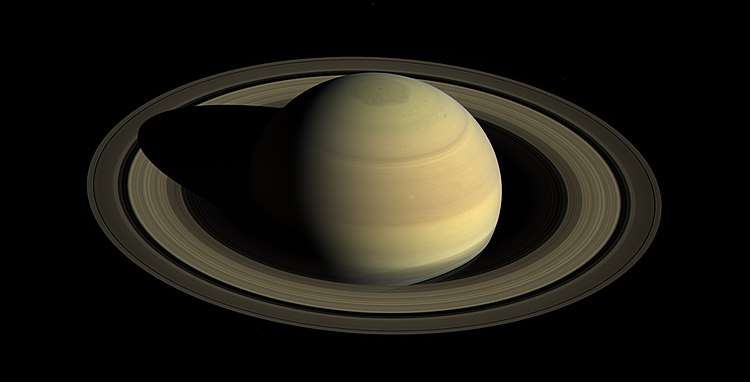

The Cassini space probe was deliberately disposed of via a controlled fall into Saturn's atmosphere on September 15, 2017, ending its nearly two-decade-long mission.[1][2][3][4] This method was chosen to prevent biological contamination of any of the moons of Saturn now thought to offer potentially habitable environments.[5] Factors that influenced the mission end method included the amount of rocket fuel left, the health of the spacecraft, and funding for operations on Earth.[6]

Some possibilities for Cassini's later stages were aerobraking into orbit around Titan,[6] leaving the Saturn system,[6] or making close approaches and/or changing its orbit.[6] For example, it could have collected solar wind data in a heliocentric orbit.[3]

End of mission options

| Color | Meaning[3] |

|---|---|

| Red | Poor |

| Orange | Fair |

| Yellow | Good |

| Green | Excellent |

During planning for its extended missions, various future plans for Cassini were evaluated on the basis of scientific value, cost, and time.[3][7] Some of the options examined included collision with Saturn atmosphere, an icy satellite, or rings; another was departure from Saturn orbit to Jupiter, Uranus, Neptune, or a centaur.[3][8] Other options included leaving it in certain stable orbits around Saturn, or departure to a heliocentric orbit.[3] Each plan required certain amounts of time and changes in velocity.[3] Another possibility was aerobraking into orbit around Titan.[6]

This table is based on page 19 of Cassini Extended Missions (NASA), from 2008.[3]

| Type | Option | Set-up requirements | Execution time | Operability + assurance of EOL |

Velocity change (Δv) required |

Science evaluation ca. 2008 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impact with ... |

Saturn's surface: short-period orbits |

High inclination achievable via any XXM design |

2–10 months total | Short time between last encounter and impact | 5–30 m/s | D-ring option satisfies unachieved AO goals; cheap and easily achievable |

| Saturn's surface: long-period orbits |

Specific orientation and inclination required | 4–22 months to set up long period orbit + 3 years for final orbit |

3 years between last encounter and impact | 5–35 m/s | Operations costs required for 3 years with no science could be applied elsewhere | |

| icy satellite | Can be implemented from any geometry | 0.5–3 months total | Short time between last encounter and impact | 5–15 m/s | Cheap and achievable anywhere/time | |

| main rings | Can be implemented from any geometry | 0.5–3 months total | Short time between last encounter and impact but difficult to prove spacecraft destruction |

5–15 m/s | Cheap and achievable anywhere/time; close-in science before impact | |

| Escape to ... |

giant planet | Specific orbit period, orientation and inclination required + specific departure dates |

1.4–2.4 years to escape + long transfer time: Jupiter 12, Uranus 20, Neptune 40 years |

Planetary impact can only be guaranteed shortly after escape for Jupiter |

5–35 m/s | Giant-planet science unlikely |

| heliocentric orbit | Can be implemented from any geometry | 9–18 months to escape, open-ended Solar orbit | Last encounter goes to escape | 5–30 m/s | Solar wind data only | |

| Centaur | Large target set offers wide range of departures |

1–2 years to escape + 3+ year transfer | Last encounter goes to escape; must maintain teams for 3+ years for centaur science |

5–30 m/s | Multi-year lifetime and funding seems better spent in target-rich Saturnian environment | |

| Stable orbit around ... |

Titan | Specific orientation and orbit period required | 13–24 months + open-ended time in stable orbit | 200 days between last encounter and final orbit | 50 m/s | Limited Saturn / magnetospheric science, but for long period of time |

| Phoebe | Specific orientation and orbit period required | 8+ years + open-ended time in stable orbit | Many months between last encounter and final orbit | 120 m/s | Solar wind data; very rare passages through magnetotail |

Atmospheric entry and destruction

On July 4, 2014, the Cassini science team announced that the proximal orbits of the probe would be named the "Grand Finale".[9] This would be immediately preceded by a gradual shift in inclination to better view Saturn's polar hexagon, and a flyby of Enceladus to more closely study its cryovolcanism.[10] This was followed by a dive into Saturn's atmosphere.[9]

Scientific data was collected using eight of its twelve science instruments. All of the probe's magnetosphere and plasma science instruments, plus the spacecraft's radio science system, and its infrared and ultraviolet spectrometers collected data during the final plunge. The data rates flowing back from Saturn could not support imaging during the final plunge, so all pictures were downlinked prior to the spacecraft disposal.[11] The predicted altitude for loss of signal was approximately 1,500 km (930 mi) above Saturn's cloud tops, when the spacecraft began to tumble and burn up like a meteor.[12]

Cassini's final transmissions were received by the Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex, located in Australia at 18:55:46 AEST. In a bittersweet ending for the scientists involved, some of whom had been involved in the mission for decades,[13][14] data was received for 30 seconds longer than anticipated, and the spacecraft's ultimate demise was predicted to have occurred within 45 seconds after that.[15] Homages were paid on social media.[16] NASA's video garnered an Emmy nomination.

See also

References

- ↑ Brown, Dwayne; Cantillo, Laurie; Dyches, Preston (September 15, 2017). "NASA's Cassini Spacecraft Ends Its Historic Exploration of Saturn". NASA. Retrieved September 15, 2017.

- ↑ Chang, Kenneth (September 14, 2017). "Cassini Vanishes Into Saturn, Its Mission Celebrated and Mourned". The New York Times. Retrieved September 15, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Spilker, Linda (April 1, 2008). "Cassini Extended Missions" (PDF). Lunar and Planetary Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 23, 2008.

- ↑ Mason, Betsy (February 3, 2010). "Cassini Gets Life Extension to Explore Saturn Until 2017". Wired. Archived from the original on February 9, 2010.

- ↑ Blabber, Phillipa; Verrecchia, Angélique (April 3, 2014). "Cassini-Huygens: Preventing Biological Contamination". Space Safety Magazine. Retrieved 2015-08-01.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bailey, Frederick; Rabstejnek, Paul. "Cassini Mission and Results". Oglethorpe University. Archived from the original on February 19, 2008.

- ↑ Pappalardo, Bob; Spilker, Linda (March 15, 2009). "Cassini Proposed Extended-Extended Mission (XXM)" (PDF). Lunar and Planetary Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 18, 2012.

- ↑ Okutsu, Masataka, et al. "Cassini End-of-Life Escape Trajectories to the Outer Planets (AAS 07-258)." ADVANCES IN THE ASTRONAUTICAL SCIENCES 129.1 (2008): 117.

- 1 2 "The Grand Finale Toolkit". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 2017-09-19.

- ↑ "Cassini Names Final Mission Phase Its 'Grand Finale'". Astrobiology Magazine. July 4, 2014. Retrieved 2015-08-01.

- ↑ Cassini conducts last picture show. Jonathan Amos. BBC News. 14 September 2017.

- ↑ Cassini Spacecraft Makes Its Final Approach to Saturn. JPL, NASA News. September 13, 2017.

- ↑ Branson-Potts, Hailey (2017-09-15). "Cassini scientists celebrate the mission's end with a few hundred of their closest friends". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2017-09-16.

- ↑ Chang, Kenneth (2017-09-15). "Cassini Vanishes Into Saturn, Its Mission Celebrated and Mourned". The New York Times. Retrieved 2017-09-16.

- ↑ Netburn, Deborah (2017-09-15). "As NASA's Cassini mission flames out over Saturn, scientists mark bittersweet end of mission". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2017-09-16.

- ↑ Kaplan, Karen (2017-09-15). "Cassini plunges to its death at Saturn, and humanity says goodbye". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2017-09-16.

Further reading

- Ralph Lorenz (2018). NASA/ESA/ASI Cassini-Huygens: 1997 onwards (Cassini orbiter, Huygens probe and future exploration concepts) (Owners' Workshop Manual). Haynes Manuals, UK. ISBN 978-1785211119.

External links

- Cassini-Huygens at ESA

- Cassini-Huygens main page at NASA

- Cassini Mission Homepage by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory

- Cassini-Huygens Mission Profile by NASA's Solar System Exploration

- Grand Finale Overview at NASA

.jpg)

.jpg)