Capture of the ''Esmeralda''

| Capture of the Esmeralda | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Peruvian War of Independence | |||||||

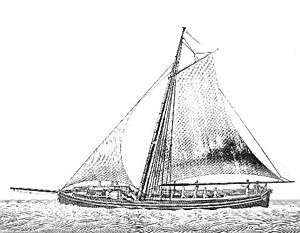

.jpg) Capture of the Esmeralda in the bay of Callao, L, Colet, Club Naval, Valparaíso. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Thomas Cochrane (WIA) |

Antonio Vacaro Juan Francisco Sánchez Luis Coig (POW-WIA) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

240 sailors & marines 14 boats |

harbor batteries 1 frigate 2 brigs 1 pailebot 14 to 24 gunboats some armed merchants | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 11 killed & 22 wounded |

1 frigate captured 3 gunboats captured various killed, wounded & prisoners | ||||||

The capture of the frigate Esmeralda was a naval action waged on the night of 5 and 6 November 1820, during a Ceasefire. [1] A division of boats with sailors and marines of the First Chilean Navy Squadron, commanded by Thomas Cochrane, stealthily advanced towards Callao and captured this ship through a boarding attack,[Note 1] being the main objective of the naval operation. It was the flagship of the Spanish fleet[2] and was protected by a strong military defense that the royalists had organized in the port.

Both Chilean[3] and Spanish[4] historiography considers that with this naval action the importance or maritime influence of the Spanish Navy in the Pacific diminished until arrives of Naval Division of Asia . The British historians Brian Vale[5] and David J. Cubitt[6] follow the same line of opinion when affirming that it lost unquestionably the control of the sea before the Chilean Navy.

Background

On 20 August 1820, the Liberating Expedition commanded by General José de San Martín sailed from Valparaíso to Peru. This force was escorted by the Chilean Navy,[Note 2] under the command of Vice Admiral Cochrane.

Since the beginning of the campaign, San Martín and Cochrane had differences regarding the military strategy that they should carry out in Peru.[8] The first wanted to avoid direct fighting, win over the population and press with indirect actions to Lima. The second wanted to give a decisive blow to the royalists, thus satisfying the need to fight that had the army and the navy. Finally, the thought of the first was the one that prevailed.

The expeditionary force arrived on 7 September in Paracas, near Pisco.[9] In the place, San Martin established his headquarters to put pressure on the royalists.[8] The Viceroy Juaquin de la Pezuela entered into negotiations with San Martin, based on the new peninsular political situation with the proclamation of the Spanish Constitution of 1812.[8] However, the negotiations that took place between the end of September and the beginning of October did not prosper.[10]

At the beginning of October, San Martin sent a division of the army to the Peruvian highlands to revolutionize the territory, giving the command of this force to General Juan Antonio Álvarez de Arenales.

On 9 October 1820, there was the lifting of the garrison of Guayaquil, which culminated in the proclamation of the independence of the place. This fact had material and moral consequences in favor of the revolutionary cause in Peru.[11]

On October 26, the expeditionary force left Pisco to the north, arriving on the 29th in front of the Callao.[12] The next day, San Martin went to Ancón to carry out military operations on land.[13] For its part, Cochrane occupied the island of San Lorenzo[14] and stayed in front of the port to establish a rigorous blockade with some of its ships.[13]

Blockade of Callao

Inactivity of the Spanish Navy

Since the arrival in September of the liberating expedition to the Peruvian coast, the Spanish Navy had not carried out any action of medium efficiency to reject or at least harass the revolutionaries, granting them an expeditious control of the sea.[15][16] This was due to the invariable defensive policy of the Viceroy Pezuela and the incompetence of the Commanding General of Navy Antonio Vacaro.[16][17]

The Spanish fleet, based in Callao, was mainly formed by the frigates Prueba, Venganza and Esmeralda, and also had several other militarily armed ships.[11] The first two frigates, commanded by Captain José Villegas, left the port on 10 October to the Peruvian south with the sole purpose of embarking troops,[18] leaving the third frigate and the other ships under the impressive defense of the port that consisted of a floating palisade that housed them inside, gunboats and batteries.[16][19] Vacaro made this third naval unit the flagship of the squadron under his command.[2]

This was the situation of the Spanish fleet at the time when Cochrane had established the blockade of Callao on 30 October, having at his disposal the frigates O'Higgins and Lautaro, and the corvette Independencia.[20]

The Cochrane plan

The blockade was maintained without difficulty by the Chilean fleet, since the Spanish fleet remained totally on the defensive. However, this situation of total inactivity bothered Cochrane due to its adventurous nature, which led him to the need to undertake some naval action.[20]

To break the monotony of the blockade, he planned to inflict a great blow on the realists in their strong defenses, similar to the capture of the defensive system of Valdivia.[20] On the basis of his own information and that of a subordinate,[21] he decided to undertake a surprise blow that consisted essentially of entering the port at night with several boats and seizing the Esmeralda by means of a boarding attack.[22][23] As a complement to his bold and ambitious plan, he intended to capture or burn the other ships.[23][24][25]

Cochrane began in those days the preparations for the attack that personally would direct, reason why it designated the crew and the officials who would participate.[26][27] For three days, the crew was trained to row silently and climb the sides of the ships, without informing them of their plan.[28] On November 1 he had given instructions for the attack on his immediate subordinates.[29] On the night of 4 November, when he had already chosen all the personnel that would accompany him in the attack, he practiced a reconnaissance in the bay, which in turn was an essay of the operation that he had decided to execute in twenty-four hours later.[26]

At dawn on 5 November, final preparations were made for the attack and a proclamation from Cochrane was read to encourage the crew.[28]

Opposing forces

Chilean Navy

Cochrane gathered 240 men for the attack, of which 160 were chosen sailors and 80 were marines.[26] It occupied 92 men of O'Higgins, 99 of Lautaro and 49 of Independencia.[28]

As for the nationality of the crew of the navy chosen for the attack, the Chilean historian Lopez Urrutia, and also Cubitt, give some figures:[Note 3]

| Name of the ship | Number of men | Chileans | Foreigners |

|---|---|---|---|

| O'Higgins | 92 | ? | ? |

| Lautaro | 99 | 43 relative | 56 relative |

| Independecia | 49 | 15 | 34 |

| Total crew | 240 | ? | ? |

| Total of officers | 32 | 5 | 27 |

They embarked on 14 boats[26] with oars, belonging to the mentioned ships, and they were divided into two groups:[25][28]

- The first group, formed by seven boats of O'Higgins, commanded by Captain Thomas Crosbie.

- The second group, formed by the same number of boats from Lautaro and Independencia, commanded by Captain Martin Guise.

Cochrane joined the first group to direct the attack,[28] leaving Captain Robert Foster in charge of all the ships.[20]

For the attack, they were armed with pistols, but also with boarding axes, daggers or machetes, and short pikes that would be essential for success.[23] His clothes would be a white jacket with a blue ribbon on his arm to recognize himself.[23] In the event that clothing is not visible in the dark, the words "Glory" and "Victory" will be used as a signal.[32]

The oars of the boats were wrapped in canvas to not produce the slightest noise when moving in the water.[23]

Spanish Navy and defense of the port

The Spanish Navy stationed in Callao, under the command of Vacaro, consisted of:[19][33]

On the frigate, in addition to the sailors, were on board a couple of troops of the Real Carlos battalion and army gunners.[35] Cubitt gives the exact number of the manning of the ship, there were 313 between officers and men.[34]

There were also 14[40] to 24[21] gunboats and an undetermined number of armed merchant ships.[15][21][33]

In addition to the naval squadron, there was the artillery of the fortresses and batteries of the port in charge of Brigadier Juan Francisco Sánchez,[26] which consisted of:[40]

- Fortresses of Real Felipe, San Rafael and San Miguel.

- Batteries of the Arsenal and San Juaquín.

The defensive formation of the realists consisted of a floating trench formed by trunks linked by chains that barely left an opening for the entry or exit of the ships of the roadstead.[33] This floating chain was guarded by the gunboats, and behind this chain were anchored the Esmeralda, Maipú (these two at the northern end of the roadstead) Pezuela and Aránzazu, forming these ships the head of the line.[19] In his rear were the armed merchant ships.[33] All this defensive disposition of the squadron was also protected by the batteries of the port.[40] It was an imposing defensive disposition.[40]

Battle

On the afternoon of 5 November, Cochrane ordered to the Lautaro and Independencia to leave the port to the high seas, leaving the O'Higgins near the island of San Lorenzo, and on one of its hidden sides the boats with their crew destined for the attack.[23] With this movement he succeeded in deceiving the royalists, making the surveillance of the port drowsy.[23]

At 10 o'clock at night, the boats separated from the O'Higgins, initiating the approach movement towards the entrance of the floating chain that protected the Spanish ships.[41] The boats advanced in two parallel columns according to the groups that formed Crosbie and Guise.[23]

The Chilean force sailed to reach the coast at the height of the battery of San Juaquín, which defended the northern end of the port, then entered between the fortress of San Miguel and the anchorage of neutral ships to hide their advance.[33] The anchorage of the neutrals was very close to the opening of the floating chain.[33] When passing through that place, they ran into the frigates USS Macedonian and HMS Hyperion,[41] which were the closest to the entrance of the realistic defense.[33] The Americans, seeing them, wished them good luck in the attack, while the British, very imprudent, began to demand the "who lives" of each of the Chilean ships, which fortunately were not heard by the royalists in the port.[41] All this silent movement carried out until now to approach the roadstead had lasted two hours.[42]

At midnight, the boats arrived at the entrance of the floating chain and saw a gunboat guarding the place, with a lieutenant and 14 men on board, so they approached stealthily and surprised her, managing to capture her with her crew and prevent them from giving the alert.[30][41] Once this obstacle was overcome, they entered the interior of the chain, and at approximately 12:30 a.m. on 6 November, they docked at the Esmeralda and boarded it from different sides simultaneously.[30] Crosbie's column, at whose head was Cochrane, attacked quickly to starboard, while Guise's column to port.[42] At that time, Coig was in the camera talking to some officers and the crew was sleeping, many of them on the deck.[27][42] Only the guards were alert to any eventuality.[Note 4]

The sleepy crew, newly aware of the surprise attack, went to take up arms to counter attack, but as Cochrane later stated: "the Chilean machetes did not give them much time to organize and recover their spirit".[44] But in spite of the surprise, they gave some resistance in the places that were attacked, giving rise to a bloody fight with sharp weapons and firearms. However, the impetus of the Chilean attack was irresistible and soon occupied some sectors such as the quarterdeck, the frigate's quarters and the stern.[45]

The royalists were pushed to the forecastle, and there they withstood the attack bravely until the forces of Crosbie and Guise united and charged resolutely upon the position.[46] Some of the attackers, who, according to the instructions, had occupied the ladders and climbed to the top in the first moments of the boarding, contributed with the victory by his shots from the height.[44] Having occupied the bow, Guise cleaned the lower deck of the troops that were firing upwards through the hatches.[46] Shortly before 1 a.m. the attackers were in possession of the ship,[47] with the realistic crew that survived surrendered.[46] During the fight, Cochrane received a blow at the beginning and in the final stage a shot that pierced his thigh, which is why he had to sit on the deck and try to direct the attack as best he could.[48]

It should be noted that the shots during the fight in the Esmeralda alerted the other ships, gunboats and batteries of the port in the middle of the darkness of the night.[49] Also the presence of some fugitive crew members of the frigate who threw themselves into the sea to save themselves and who informed that it had been captured.[49]

When the fight ended in the Esmeralda, Cochrane tried to put into practice the complement of his plan, but without success.[Note 5] This was due to the fact that several members of the crew, in the midst of the joy of victory, began to loot the ship and got drunk with the alcohol they found.[50] Indeed, when some officers urged them to embark on the boats to continue the attack on the other Spanish ships, they flatly refused, saying that they had done enough.[46] The few sailors that the officers managed to embark[51] attacked Maipú and Pezuela, but were rejected because these ships were already prepared and had the support of several gunboats directed by the same Vacaro, who was patrolling the bay at the time of the attack. However, the Spanish boss could not do anything to try to recover his flagship.[52]

Finally, Cochrane ordered Guise to take the Esmeralda out of the bay, beginning to move outward along with all the boats and 2 captured gunboats; the one that observed at the entrance of the floating chain and another that had approached the frigate during the climax of the fight.[52] The batteries of the port, observing that and understanding the situation, began to discharge all their artillery fire to prevent its removal.[53] The ships and gunboats also fired at him. Several shots hit him, one entered through one of the stern windows and damaged the quarterdeck, which caused the death of some men and wounded Coig, who was imprisoned there since the attackers took that sector during boarding.[53]

In these circumstances, the neutral ships USS Macedonian and HMS Hyperion began to move away from the bay to get out of reach of the batteries due to the danger of the shots.[52] At the same time, they placed certain lamps in their rigging that were the signals agreed with the port authorities so that, in case of confrontations, they were not attacked.[53] Cochrane realized this and, understanding its meaning, ordered to place identical lamps in the Esmeralda.[53] This fact caused confusion in the batteries that could not determine which of the three ships with lights was the captured frigate, showing reticence to direct their shots to the foreign ships, so that at approximately 1:15 a.m. they began to decrease.[54]

The Esmeralda followed the path to leave the port and around 2:30 a.m. anchored out of range of batteries near the O'Higgins.[55] With it came all the smaller boats, towing the two captured gunboats. A little known fact referred by an eyewitness of the attacking forces states that one of the boats of the O'Higgins had gone astray, and that during the rest of the night the batteries continued to open fire, without understanding the reason.[56] The doubts disappeared when the sun appeared and the missing boat was seen leaving the port, towing a large gunboat that had captured, so he quickly received help from his comrades to leave the place.[56]

Aftermath

Analysis

The Chilean historian Barros Arana indicates in his book written in 1894 that this fact has been mentioned in numerous written works, citing some, considering it therefore as the battle of the Spanish American wars of independence that has been narrated in a greater amount of times.[57] The Spanish historian Fernández Duro compares this naval action with the capture of the Hermione, in Puerto Cabello, in 1799, but affirming that he surpasses it in daring.[37]

Notes

- ↑ In naval terms, this naval tactic is called a "cutting out operation".

- ↑ The squadron was formed by the frigate O'Higgins (flagship), ship of the line San Martín, frigate Lautaro, corvette Independencia, the brigs Galvarino, Pueyrredón and Araucano, and schooner Moctezuma.[7]

- ↑ With respect to the 27 foreign officers, Cubitt indicates that they were all British or North American,[30] and López Urrutia simply understands that they were all foreigners.[28] Of the 5 remaining officers, Cubitt is silent,[30] but López Urrutia clarifies that they were Chilean.[28] With respect to the foreign crew, neither Lopez Urrutia[28] nor Cubitt (except the officers)[30] specifies the nationality of the crew, although it is very probable that most of them are British or North American or that all have been of those nationalities. This could be due to the fact that both components were among the majority of the foreigners of the Chilean Navy. As for the 92 crew members of O'Higgins, López Urrutia[28] and Cubitt[30] are silent about their nationality, but the Chilean historian Luis Uribe, based on the official part of Cochrane, indicates the presence of Chilean and foreign components.[31] With respect to the 99 members of Lautaro, López Urrutia[28] indicates that half of them were Chilean and Cubitt[30] indicates that almost half (43) were Chilean.

- ↑ There are historiographical differences with respect to the moment in which the realists noticed the surprise attack. The Chilean historian Barros Arana,[43] the British historian Brian Vale[27] and the Spanish historian Fernandez Duro[40] indicate that they realized the surprise when this stratagem had already been completed with the boarding of the Esmeralda. The British historian J. Cubitt[30] and the Peruvian historian Sotelo[33] indicate that the Chilean boats were sighted during their approach to the ship, but equally surprised by their proximity and fast boarding.

- ↑ Cochrane had planned to use the captured frigate as a platform from which to attack other vessels in the harbor. Some of the junior officers had orders to attack Maipú and Pezuela, and other officers were ordered to throw adrift the other heavy ships and merchant ships that were nearby.[46]

References

- ↑ On November 5 they were in ceasefire for a exchange of prisoners with General Jose de San Martin. Gaspar Pérez Turrado (1996). Page 167

- 1 2 Fernández Duro 1903, p. 295.

- ↑ Vázquez de Acuña 2003, p. 164.

- ↑ Fernández Duro 1903, p. 297.

- ↑ Vale 2008, pp. 115–116.

- ↑ Cubitt 1974, p. 309.

- ↑ López Urrutia 2008, p. 143.

- 1 2 3 Vázquez de Acuña 2003, p. 159.

- ↑ López Urrutia 2008, p. 144.

- ↑ Vázquez de Acuña 2003, p. 160.

- 1 2 Barros Arana 1894, p. 98.

- ↑ Barros Arana 1894, pp. 87–88.

- 1 2 Barros Arana 1894, p. 89.

- ↑ Fernández Duro 1903, p. 296.

- 1 2 López Urrutia 2008, p. 145.

- 1 2 3 Vázquez de Acuña 2003, p. 161.

- ↑ Fernández Duro 1903, pp. 294–295.

- ↑ Ortiz Sotelo 2015, p. 372.

- 1 2 3 Fernández Duro 1903, pp. 297–298.

- 1 2 3 4 López Urrutia 2008, p. 147.

- 1 2 3 Cubitt 1974, p. 300.

- 1 2 Vale 2008, p. 111.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Barros Arana 1894, p. 100.

- ↑ López Urrutia 2008, pp. 149–150.

- 1 2 Cubitt 1974, p. 301.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Barros Arana 1894, p. 99.

- 1 2 3 Vale 2008, p. 112.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 López Urrutia 2008, p. 148.

- ↑ López Urrutia 2008, p. 149.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Cubitt 1974, p. 302.

- ↑ Uribe 1892, p. 216.

- ↑ Ureta Muñoz 1993, p. 3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Ortiz Sotelo 2015, p. 373.

- 1 2 Cubitt 1974, p. 293.

- ↑ Ortiz Sotelo 2015, p. 374.

- ↑ Ortiz Sotelo 2015, p. 419.

- 1 2 Fernández Duro 1903, p. 299.

- 1 2 Ortiz Sotelo 2015, p. 421.

- 1 2 Ortiz Sotelo 2015, p. 434.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fernández Duro 1903, p. 298.

- 1 2 3 4 López Urrutia 2008, p. 150.

- 1 2 3 Barros Arana 1894, p. 101.

- ↑ Barros Arana 1894, pp. 101-102.

- 1 2 Barros Arana 1894, p. 102.

- ↑ Vale 2008, pp. 112–113.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Vale 2008, p. 113.

- ↑ Cubitt 1974, p. 304.

- ↑ López Urrutia 2008, p. 151.

- 1 2 Barros Arana 1894, p. 103.

- ↑ Barros Arana 1894, p. 104.

- ↑ Cubitt 1974, pp. 304–305.

- 1 2 3 López Urrutia 2008, p. 152.

- 1 2 3 4 Cubitt 1974, p. 305.

- ↑ Cubitt 1974, pp. 305–306.

- ↑ Cubitt 1974, p. 306.

- 1 2 López Urrutia 2008, pp. 153–154.

- ↑ Barros Arana 1894, pp. 104–105.

Bibliography

- Barros Arana, Diego (1894). Historia General de Chile (in Spanish). XIII. Santiago, Chile: Imprenta Cervantes.

- López Urrutia, Carlos (2007). Historia de la Marina de Chile (in Spanish). Segunda Edición. Santiago, Chile: El Ciprés Editores. ISBN 978-0-6151-8574-3.

- Fernández Duro, Cesáreo (1903). Armada Española desde la unión de los reinos de Castilla y Aragón (in Spanish). IX. Madrid, España: Instituto de Historia y Cultura Naval.

- Vale, Brian (2008). Cochrane in the Pacific: Fortune and Freedom in Spanish America. London, England: I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-446-6.

- Vázquez de Acuña, Isidoro (2003). Estertores Navales Realistas (in Spanish). Santiago, Chile: Anales del Instituto de Chile.

- Cubitt, David John (1974). Lord Cochrane and the Chilean Navy, 1818-1823. Edinburgh, Scotland: University of Edinburgh Ph D Thesis.

- Ortiz Sotelo, Jorge (2015). La Real Armada en el Pacífico Sur (in Spanish). Capitulo 9 y Anexo 2. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas, Bonilla Artigas Editores. ISBN 978-607-8348-61-9.

- Ureta Muñoz, Jorge (1993). "Captura de la fragata española "Esmeralda" en el Callao, bajo la perspectiva de las operaciones especiales" (PDF) (in Spanish). Viña del Mar, Chile: Revista de Marina de la Armada de Chile.

External links

- Captura de la "Esmeralda" - 5 y 6 de noviembre de 1820 – Official site of the Chilean Navy. (in Spanish)