Cadmium selenide

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Selanylidenecadmium[1] | |

| Other names | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.013.772 |

| EC Number | 215-148-3 |

| 13656 | |

| MeSH | cadmium+selenide |

PubChem CID |

|

| RTECS number | EV2300000 |

| UN number | 2570 |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| CdSe | |

| Molar mass | 191.39 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Black, translucent, adamantine crystals |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 5.81 g cm−3[3] |

| Melting point | 1,240 °C (2,260 °F; 1,510 K)[3] |

| Band gap | 1.74 eV, both for hex. and sphalerite[4] |

Refractive index (nD) |

2.5 |

| Structure | |

| Wurtzite | |

| C6v4-P63mc | |

| Hexagonal | |

| Hazards | |

| GHS pictograms |    |

| GHS signal word | DANGER |

| H301, H312, H331, H373, H410 | |

| P261, P273, P280, P301+310, P311, P501 | |

| US health exposure limits (NIOSH): | |

PEL (Permissible) |

[1910.1027] TWA 0.005 mg/m3 (as Cd)[5] |

REL (Recommended) |

Ca[5] |

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

Ca [9 mg/m3 (as Cd)][5] |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions |

Cadmium oxide, Cadmium sulfide, Cadmium telluride |

Other cations |

Zinc selenide, Mercury(II) selenide |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Cadmium selenide is an inorganic compound with the formula CdSe. It is a black to red-black solid that is classified as a II-VI semiconductor of the n-type. Much of the current research on cadmium selenide is focused on its nanoparticles.

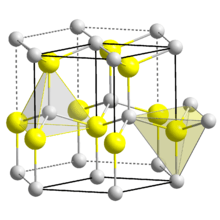

Structure

Three crystalline forms of CdSe are known: wurtzite (hexagonal), sphalerite (cubic) and rock-salt (cubic). The sphalerite CdSe structure is unstable and converts to the wurtzite form upon moderate heating. The transition starts at about 130 °C, and at 700 °C it completes within a day. The rock-salt structure is only observed under high pressure.[6]

Production

The production of cadmium selenide has been carried out in two different ways. The preparation of bulk crystalline CdSe is done by the High-Pressure Vertical Bridgman method or High-Pressure Vertical Zone Melting.[7]

Cadmium selenide may also be produced in the form of nanoparticles. (see applications for explanation) Several methods for the production of CdSe nanoparticles have been developed: arrested precipitation in solution, synthesis in structured media, high temperature pyrolysis, sonochemical, and radiolytic methods are just a few.[8][9]

Production of cadmium selenide by arrested precipitation in solution is performed by introducing alkylcadmium and trioctylphosphine selenide (TOPSe) precursors into a heated solvent under controlled conditions.[10]

- Me2Cd + TOPSe → CdSe + (byproducts)

CdSe nanoparticles can be modified by production of two phase materials with ZnS coatings. The surfaces can be further modified, e.g. with mercaptoacetic acid, to confer solubility. [11]

Synthesis in structured environments refers to the production of cadmium selenide in liquid crystal or surfactant solutions. The addition of surfactants to solutions often results in a phase change in the solution leading to a liquid crystallinity. A liquid crystal is similar to a solid crystal in that the solution has long range translational order. Examples of this ordering are layered alternating sheets of solution and surfactant, micelles, or even a hexagonal arrangement of rods.

High temperature pyrolysis synthesis is usually carried out using an aerosol containing a mixture of volatile cadmium and selenium precursors. The precursor aerosol is then carried through a furnace with an inert gas, such as hydrogen, nitrogen, or argon. In the furnace the precursors react to form CdSe as well as several by-products.[8]

CdSe nanoparticles

CdSe-derived nanoparticles with sizes below 10 nm exhibit a property known as quantum confinement. Quantum confinement results when the electrons in a material are confined to a very small volume. Quantum confinement is size dependent, meaning the properties of CdSe nanoparticles are tunable based on their size.[12] One type of CdSe nanoparticle is a CdSe quantum dot. This discretization of energy states results in electronic transitions that vary by quantum dot size. Larger quantum dots have closer electronic states than smaller quantum dots which means that the energy required to excite an electron from HOMO to the LUMO is lower than the same electronic transition in a smaller quantum dot. This quantum confinement effect can be observed as a red shift in absorbance spectra for nanocrystals with larger diameters.

CdSe quantum dots have been implemented in a wide range of applications including solar cells,[13] light emitting diodes,[14] and biofluorescent tagging. CdSe-based materials also have potential uses in biomedical imaging. Human tissue is permeable to near infra-red light. By injecting appropriately prepared CdSe nanoparticles into injured tissue, it may be possible to image the tissue in those injured areas.[15][16]

CdSe quantum dots are usually composed of a CdSe core and a ligand shell. Ligands play important roles in the stability and solubility of the nanoparticles. During synthesis, ligands stabilize growth to prevent aggregation and precipitation of the nanocrystals. These capping ligands also affect the quantum dot’s electronic and optical properties by passivating surface electronic states.[17] An application that depends on the nature of the surface ligands is the synthesis of CdSe thin films.[18][19] The density of the ligands on the surface and the length of the ligand chain affect the separation between nanocrystal cores which in turn influence stacking and conductivity. Understanding the surface structure of CdSe quantum dots in order to investigate the structure’s unique properties and for further functionalization for greater synthetic variety requires a rigorous description of the ligand exchange chemistry on the quantum dot surface.

A prevailing belief is that trioctylphosphine oxide (TOPO) or trioctylphosphine (TOP), a neutral ligand derived from a common precursor used in the synthesis of CdSe dots, caps the surface of CdSe quantum dots. However, results from recent studies challenge this model. Using NMR, quantum dots have been shown to be nonstoichiometric meaning that the cadmium to selenide ratio is not one to one. CdSe dots have excess cadmium cations on the surface that can form bonds with anionic species such as carboxylate chains.[20] The CdSe quantum dot would be charge unbalanced if TOPO or TOP were indeed the only type of ligand bound to the dot.

The CdSe ligand shell may contain both X type ligands which form covalent bonds with the metal and L type ligands that form dative bonds. It has been shown that these ligands can undergo exchange with other ligands. Examples of X type ligands that have been studied in the context of CdSe nanocrystal surface chemistry are sulfides and thiocyanates. Examples of L type ligands that have been studied are amines and phosphines (ref). A ligand exchange reaction in which tributylphosphine ligands were displaced by primary alkylamine ligands on chloride terminated CdSe dots has been reported.[21] Stoichiometry changes were monitored using proton and phosphorus NMR. Photoluminescence properties were also observed to change with ligand moiety. The amine bound dots had significantly higher photoluminescent quantum yields than the phosphine bound dots.

Applications

CdSe material is transparent to infra-red (IR) light and has seen limited use in photoresistors and in windows for instruments utilizing IR light. The material is also highly luminescent.[22]

Safety information

Cadmium is a toxic heavy metal and appropriate precautions should be taken when handling it and its compounds. Selenides are toxic in large amounts. Cadmium selenide is a known carcinogen to humans and medical attention should be sought if swallowed or if contact with skin or eyes occurs.[23][24]

References

- ↑ "cadmium selenide – PubChem Public Chemical Database". The PubChem Project. USA: Nation Center for Biotechnology Information. Descriptors Computed from Structure.

- 1 2 "cadmium selenide (CHEBI:50834)". Chemical Entities of Biological Interest (ChEBI). UK: European Bioinformatics Institute. IUPAC Names.

- 1 2 Haynes, William M., ed. (2011). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (92nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. 4.54. ISBN 1439855110.

- ↑ Ninomiya, Susumu; Adachi, Sadao (1995). "Optical properties of cubic and hexagonal Cd Se". Journal of Applied Physics. 78 (7): 4681. Bibcode:1995JAP....78.4681N. doi:10.1063/1.359815.

- 1 2 3 "NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards #0087". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ↑ Lev Isaakovich Berger (1996). Semiconductor materials. CRC Press. p. 202. ISBN 0-8493-8912-7.

- ↑ II-VI compound crystal growth, HPVB & HPVZM basics

- 1 2 Didenko, Yt; Suslick, Ks (Sep 2005). "Chemical aerosol flow synthesis of semiconductor nanoparticles". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 127 (35): 12196–7. doi:10.1021/ja054124t. ISSN 0002-7863. PMID 16131177.

- 1 2 Haitao Zhang; Bo Hu; Liangfeng Sun; Robert Hovden; Frank W. Wise; David A. Muller; Richard D. Robinson (Sep 2011). "Surfactant Ligand Removal and Rational Fabrication of Inorganically Connected Quantum Dots". Nano Letters. 11 (12): 5356–5361. Bibcode:2011NanoL..11.5356Z. doi:10.1021/nl202892p. PMID 22011091.

- ↑ Murray, C. B.; Norris, D. J.; Bawendi, M. G. (1993). "Synthesis and characterization of nearly monodisperse CdE (E = sulfur, selenium, tellurium) semiconductor nanocrystallites". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 115 (19): 8706–8715. doi:10.1021/ja00072a025.

- ↑ Somers, Rebecca C.; Bawendi, Moungi G.; Nocera, Daniel G. (2007). "CdSe nanocrystal based chem-/bio- sensors". Chemical Society Reviews. 36 (4): 579–591. doi:10.1039/B517613C.

- ↑ Nanotechnology Structures – Quantum Confinement

- ↑ Robel, I.; Subramanian, V.; Kuno, M.; Kamat, P.V. (2006). "Quantum Dot Solar Cells. Harvesting Light Energy with CdSe Nanocrystals Molecularly Linked to Mesoscopic TiO2 Films". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128 (7): 2385–2393. doi:10.1021/ja056494n.

- ↑ Colvin, V. L.; Schlamp, M. C.; Alivisatos, A. P. (1994). "Light-emitting diodes made from cadmium selenide nanocrystals and a semiconducting polymer". Nature. 370 (6488): 354–357. Bibcode:1994Natur.370..354C. doi:10.1038/370354a0.

- ↑ Chan, W. C.; Nie, S. M. (1998). "Quantum Dot Bioconjugates for Ultrasensitive Nonisotopic Detection". Science. 281 (5385): 2016–8. Bibcode:1998Sci...281.2016C. doi:10.1126/science.281.5385.2016. PMID 9748158.

- ↑ Bruchez, M.; Moronne, M.; Gin, P.; Weiss, S.; Alivisatos, A. P. (1998). "Semiconductor nanocrystals as fluorescent biological labels". Science. 281 (5385): 2013–6. Bibcode:1998Sci...281.2013B. doi:10.1126/science.281.5385.2013. PMID 9748157.

- ↑ Murray, C. B.; Kagan, C. R.; Bawendi, M. G. (2000). "Synthesis and Characterization of Monodisperse Nanocrystals and Close-packed Nanocrystal Assemblies". Annu. Rev. Mater. Sci. 30: 545–610. Bibcode:2000AnRMS..30..545M. doi:10.1146/annurev.matsci.30.1.545.

- ↑ Murray, C. B.; Kagan, C. R.; Bawendi, M. G. (1995). "Self-Organization of CdSe Nanocrystallites into Three-Dimensional Quantum Dot Superlattices". Science. 270 (5240): 1335–1338. Bibcode:1995Sci...270.1335M. doi:10.1126/science.270.5240.1335.

- ↑ Islam, M. A.; Xia, Y. Q.; Telesca, D. A.; Steigerwald, M. L.; Herman, I. P. (2004). "Controlled Electrophoretic Deposition of Smooth and Robust Films of CdSe Nanocrystals". Chem. Mater. 16: 49–54. doi:10.1021/cm0304243.

- ↑ Owen, J. S.; Park, J.; Trudeau, P.E.; Alivisatos, A. P. (2008). "Reaction chemistry and ligand exchange at cadmium-selenide nanocrystal surfaces". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130 (37): 12279–12281. doi:10.1021/ja804414f.

- ↑ Anderson, N. A.; Owen, J. S. (2013). "Soluble, Chloride-Terminated CdSe Nanocrystals: Ligand Exchange Monitored by 1H and 31P NMR Spectroscopy". Chem. Mater. 25: 69–76. doi:10.1021/cm303219a.

- ↑ Efros, Al. L.; Rosen, M. (2000). "The electronic structure of semiconductor nanocrystals". Annual Review of Materials Science. 30: 475–521. Bibcode:2000AnRMS..30..475E. doi:10.1146/annurev.matsci.30.1.475.

- ↑ Additional safety information available at www.msdsonline.com, search 'cadmium selenide' (must register to use).

- ↑ CdSe Material Safety Data Sheet. sttic.com.ru

External links

- National Pollutant Inventory – Cadmium and compounds

- Nanotechnology Structures – Quantum Confinement

- thin-film transistors (TFTs). J. DeBaets et al., "High-voltage polycrystalline CdSe thin-film transistors", IEEE Trans. Electron Devices, vol. ED-37, pp. 636–639, Mar. 1990, doi:10.1109/16.47767.

- T Ohtsuka; J Kawamata; Z Zhu; T Yao (1994). "p-type CdSe grown by molecular beam epitaxy using a nitrogen plasma source". Applied Physics Letters. 65 (4): 466. Bibcode:1994ApPhL..65..466O. doi:10.1063/1.112338.

- Ma, C; Ding, Y; Moore, D; Wang, X; Wang, Zl (Jan 2004). "Single-crystal CdSe nanosaws". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 126 (3): 708–9. doi:10.1021/ja0395644. ISSN 0002-7863. PMID 14733532.

- Califano, Marco; Zunger, Alex; Franceschetti, Alberto (2004). "Direct carrier multiplication due to inverse Auger scattering in CdSe quantum dots". Applied Physics Letters. 84 (13): 2409. Bibcode:2004ApPhL..84.2409C. doi:10.1063/1.1690104.

- Schaller, Richard D.; Petruska, Melissa A.; Klimov, Victor I. (2005). "Effect of electronic structure on carrier multiplication efficiency: Comparative study of PbSe and CdSe nanocrystals". Applied Physics Letters. 87 (25): 253102. Bibcode:2005ApPhL..87y3102S. doi:10.1063/1.2142092.

- Hendry, E.; Koeberg, M; Wang, F; Zhang, H; De Mello Donegá, C; Vanmaekelbergh, D; Bonn, M (2006). "Direct Observation of Electron-to-Hole Energy Transfer in CdSe Quantum Dots" (PDF). Physical Review Letters. 96 (5): 057408. Bibcode:2006PhRvL..96e7408H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.057408. PMID 16486988. *