Butovo firing range

| Бутовский полигон | |

Wayside cross in Butovo | |

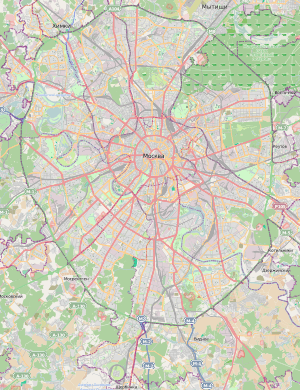

Moscow and vicinity | |

| Details | |

|---|---|

| Established | August 1937 |

| Country | Russian Federation |

| Coordinates | 55°31′51.96″N 37°35′40.92″E / 55.5311000°N 37.5947000°E |

| Owned by | Russian Orthodox Church |

The Butovo Firing Range or Butovo Shooting Range, (Russian: Бутовский полигон) is a former private estate near the village of Drozhzhino (Russian: Дрожжино) in the Yuzhnoye Butovo District south of Moscow that was seized by the Soviets after the 1917 revolution and thereafter used by secret police as an agricultural colony, shooting range, and from 1938 to 1953, as a site for executions and mass graves of persons deemed "enemies of the people." The exact number of victims executed remains unknown, as only fragmentary data has been declassified by NKVD's successor services.[1] However, between 1937 and 1938, the height of Josef Stalin's Great Terror, 20,761 prisoners[2] were transported to the site and executed, typically by gunshot to the back of the head.[3] Notable victims included Béla Kun, Gustav Klutsis, Seraphim Chichagov, as well as over 1000 members of the Russian Orthodox clergy.[4] The Russian Orthodox Church took over the ownership of the lot in 1995 and erected a large Russian Revival memorial church. The mass grave may be visited on weekends.

History

First mentioned in historical texts in 1568 as owned by a local boyar Fyodor Drozhin, the area was occupied by the small settlement of Kosmodemyanskoye Drozhino (named after Saints Cosmas and Damian) until the 19th century. In 1889 the estate's owner, N.M. Solovov, turned it into a large stud farm with stables and a racetrack. His descendant, I.I. Zimin, donated the farm to the state in the aftermath of the October Revolution in exchange for the right to flee the country. The farm then became the property of the Red Army.[5]

In the 1920s, the Red Army ceded the site, now officially named Butovo, to the OGPU, the Soviet secret police, as an agricultural colony. After the OGPU was incorporated into the Security and Intelligence Agency (NKVD) in 1934, a portion of the property was encircled by a high fence and transformed into a small firing range. The remaining grounds were occupied by a sovkhoz (Soviet state farm), and the Kommunarka, which contained the dacha of the NKVD’s director, Genrikh Yagoda.

Great Purges

On July 31, 1937, the NKVD issued Decree No. 00447 "On the operation of repressing former kulaks, criminals and other anti-Soviet elements." [6] The political repression that followed resulted in large death sentence and execution quotas. Local cemeteries in Moscow were unable to accommodate the sheer volume of purge victims executed in area prisons. To address the issue, the NKVD allocated two new special facilities - Butovo and Kommunarka - to serve as a combination of execution site and mass grave.[7]

The first 91 victims were transported to Butovo from Moscow prisons on August 8, 1937.[2] Over the next 14 months, 20,761 were executed and buried at the site, with another 10,000 to 14,000 shot and buried at the nearby Kommunarka Firing Range.[8] On average, 50 persons were executed per day during the purge. Some days saw no executions, while on others hundreds were shot.[2] Records indicate the busiest day was February 28,1938 when 562 people were executed.[9]

Execution Process

Victims were rounded up as soon as sentences were handed down by non-judicial organs; committees of three “troikas”, or two persons “dvoika” or the military tribunal of the Supreme Court.[8] They were then transported to Butovo in trucks marked “Bread” or "Meat" to disguise operations from area residents. Some prisoners would be immediately killed upon arrival when their truck was flooded with carbon monoxide, and the bodies then disposed of in nearby ditches.[10][11] Most were led to a long barrack, ostensibly for a medical exam,[12] where there was a roll call and reconciliation of people with file dossiers including photos. (These same photos from NKVD files would later serve as memorials to victims). Only after the paperwork was complete would they pronounce the death sentence. After sunrise, NKVD officers, often drunk off the bucket of vodka provided to them,[2] would escort prisoners away from the barracks and shoot them at close range to the back of the head, often with a Nagan revolver pistol.[7] Many died without understanding what crimes they had been accused of. Those shot were immediately or a short time afterwards dumped into one of 13 ditches, totaling 900 meters in length. The width of each ditch was 4-5 meters, and the depth approximately 4 meters.[13] Executions and burials were made without notice to relatives and without church or civil funeral services. Relatives of those who were shot only began to receive certificates indicating the exact date and cause of death in 1989.

Victims

Victims came from all parts of Soviet society. They were workers , peasants, priests , kulaks, former White Guards and other "anti-Soviet elements," pre-revolutionary Russian elite, Bolshevik old guard, generals, sportsmen, aviators and artists, “dangerous social elements” such as tramps, beggars, thieves, petty criminals, and those guilty of “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda."[8] They were overwhelmingly male (95.86%) and most were between 25 and 50 years old when they died. Among those executed, 18 persons were older than 75 and 10 were children 15 years old and younger.[14] The youngest person executed was 13-year-old Misha Shamonin, an orphan street boy, for the theft of two loaves of bread.[15] More than 60 different nationalities are also represented among the victims including French, Americans, Italians, Chinese, and Japanese.[16] Nearly 1000 Russian Orthodox clergy were executed at Butovo, as well as Lutheran, Protestant, and Catholics clergy (mostly from Poland or Austria).[8]

The last 52 victims of Stalin’s purges were executed at Butovo on October 19, 1938.[2] Afterwards, the landfill continued to be used for the burial of those who were shot in Moscow prisons. During World War II, a German prisoner of war camp was established near the site. Prisoners were used as forced labor to build the Warsaw Highway; those who were too ill or exhausted to work were shot and thrown into the ditches.[17] The commandant's office was located just 100 meters from the funerary ditches, and later became a retreat for senior NKVD officers often visited by Lavrenty Beria.[18] Nevertheless, executions continued at nearby locations such as Sukhanovka and Kommunarka until at least 1941[8] and likely onto 1953. In particular, the Kommunarka witnessed executions of high profile political and public figures from Lithuania , Latvia , Estonia , and Comintern leaders from Germany , Romania , France , Turkey , Bulgaria , Finland , Hungary. Mongolia’s top leadership, including former Prime Minister A. Amar and 28 associates, were executed at Kommunarka on July 27, 1941.[19]

Notable deaths

Among those killed and buried at Butovo were Soviet military commander Hayk Bzhishkyan; Tsarist statesman Vladimir Dzhunkovsky; Bolshevik revolutionary and politician Nikolai Krylenko; the former leader of Hungary Béla Kun, during its brief Communist regime; the painter Aleksandr Drevin, film actress Marija Leiko, and photographer Gustav Klutsis who were all Latvian; Orthodox bishop Seraphim Chichagov, and Prince Dmitry Shakhovskoy. former President of the State Duma F. Golovin, Nikolai Danilevsky, the first Russian aviator; Otto Shmidt, an arctic explorer; Mikhail Khitrovo-Kramskoi, a composer; five tsarist generals and representatives of Russian noble families such as the Rostopchins, the Tuchkovs, the Gagarins, the Obolenskys, the Olsufiyevs, and the Bibikovs.[20]

German Communist Party (KPD) members were also among the victims, for example, Hermann Taubenberger and Walter Haenisch. Over two hundred were shot with the explicit approval of KPD leaders Wilhelm Pieck and Walter Ulbricht, having been betrayed to the NKVD, it is said, by Herbert Wehner, then still a member of the KPD Politburo.[21]

- Victims of the Stalinist Purges who died at Butovo

Seraphin (Chichagov), before being sentenced to death and shot.

Seraphin (Chichagov), before being sentenced to death and shot. Béla Kun after arrest by NKVD 1937

Béla Kun after arrest by NKVD 1937 Jukums Vācietis: Latvian Soviet military commander

Jukums Vācietis: Latvian Soviet military commander Mural displaying images of victims at Butovo

Mural displaying images of victims at Butovo

Legacy

The Butovo Firing Range was heavily guarded by Soviet and later Russian secret police until 1995. On June 7, 1993 a small group of activists, officials, and some relatives of those who died at Butovo, visited the site. In October of that same year a plaque was inaugurated that read “In this zone of the Butovo shooting range, several thousand people were, in 1937-1938, shot in secret and buried."[22] A year later, Russian Orthodox Church interest in the site was piqued when archivists discovered that a senior figure of the church, Seraphim, the Metropolitan of Leningrad, was killed there. In 1995, Russian security agencies transferred both Butovo and Kommunarka to the Orthodox Church for “use without time limit”[22] A small wooden church, the Church of the New Martyrs and Confessors of Russia, was inaugurated on June 16, 1996. The Church of the Resurrection, a larger white stone structure, was completed in 2007.[23]

On October 30, 2007 Russian President Vladimir Putin commemorated the 70th anniversary of the repressions by visiting the Butovo Firing Range.[2] There, Putin attributed the deaths of so many to the “excesses of the political conflict.” Critics have pointed out this statement signaled the failure of Putin, and perhaps Russian society as a whole, to come to grips with the fact that the victims of Butovo were killed not because they were political opponents of Stalin, but simply because of their backgrounds, nationalities, or that they simply were caught up in the purge mechanism that sought to repress or eliminate large swaths of potential dissenters to Stalin’s rule.

In September 2017, a new memorial, “Garden of Memory”, was opened. The monument consists of two granite slabs on which are engraved the names of 20,762 people who died at Butovo. The monument measures 984 ft. long, and 6.5 ft. tall.[7]

See also

References

- ↑ Бутовский полигон. 1937—1938. Книга памяти жертв политических репрессий (in Russian). 1–7. Moscow: Memorial. 1997–2003.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Christensen, Karin Hyldal (2017-10-02). The Making of the New Martyrs of Russia: Soviet Repression in Orthodox Memory. Routledge. ISBN 9781351850353.

- ↑ Snyder, Timothy (2012-10-02). Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. Basic Books. p. 83. ISBN 9780465032976.

- ↑ Kenworthy, Scott Mark (2010-10-08). The Heart of Russia: Trinity-Sergius, Monasticism, and Society after 1825. Oxford University Press. p. 364. ISBN 9780199379415.

- ↑ "Butovo Polygon – Smoke of the Fatherland". blogs.carleton.edu. Retrieved 2018-08-17.

- ↑ Khlevniuk, Oleg V.; Nordlander, David J. (2004). The History of the Gulag: From Collectivization to the Great Terror. Yale University Press. p. 145. ISBN 0300092849.

- 1 2 Stala, Krzysztof; Willert, Trine Stauning (2012-01-01). Rethinking the Space for Religion: New Actors in Central and Southeast Europe on Religion, Authenticity and Belonging. Nordic Academic Press. p. 215. ISBN 9789187121852.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Schlögel, Karl (2014-01-08). Moscow, 1937. John Wiley & Sons. p. 118. ISBN 9780745683621.

- ↑ Vladimir Kuzmin (31 October 2007). Поминальная молитва; Владимир Путин посетил Бутовский полигон, где похоронены жертвы массовых расстрелов. Rossiyskaya Gazeta (in Russian) (4506). Retrieved 2011-10-18.

- ↑ Timothy J. Colton. Moscow: Governing the Socialist Metropolis. Belknap Press, 1998. ISBN 0-674-58749-9 p. 286

- ↑ Yevgenia Albats, KGB: The State Within a State. 1995, page 101. According to Yevgenia Albats, "Owning to the shortage of executioners, ... Chekists used trucks camouflaged as bread vans for mobile death chambers. Yes, the very same machinery made notorious by the Nazis - yes, these trucks were originally a Soviet invention, in use years before the ovens of the Auschwitz were built"

- ↑ Robbins, Richard G. (2018-02-16). Overtaken by the Night: One Russian's Journey through Peace, War, Revolution, and Terror. University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 9780822983224.

- ↑ "Бутовский полигон" (in Russian). Retrieved 2018-08-17.

- ↑ GOLOVKOVA, Lidija. 1997-2004, Butovskij Polygon. 1937-1938: kniga Pamjati žertv politiceskih repressij, [“Butovo’s Shooting range, 1937-1938: Book of memory of the victims of political repression”],. p. 302.

- ↑ Hades, Lena (2016-03-25). "Stalin's Great Purge: Boy Executed For Two Loaves Of Bread". Huffington Post. Retrieved 2018-08-17.

- ↑ Braithwaite, Rodric (2010-12-09). Moscow 1941: A City & Its People at War. Profile Books. p. 48. ISBN 1847650627.

- ↑ Оберемко, Валентина. "Двуликое Бутово.Когда-то этот район был шикарной «Рублёвкой»". www.aif.ru. Retrieved 2018-08-17.

- ↑ "Бутовский полигон" (in Russian). Retrieved 2018-08-17.

- ↑ "Спецобъект "Монастырь"". Известия (in Russian). 2007-10-11. Retrieved 2018-08-17.

- ↑ "Mass Grave in Moscow Suburbs is Among Russia's Holiest Sites". Retrieved 2018-08-17.

- ↑

- 1 2 Dwyer, Philip; Ryan, Lyndall (2012-04-01). Theatres Of Violence: Massacre, Mass Killing and Atrocity throughout History. Berghahn Books. p. 192. ISBN 9780857453006.

- ↑ Kishkovsky, Sophia. "Former Killing Ground Becomes Shrine to Stalin's Victims". Retrieved 2018-08-17.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Butovo firing range. |