Genrikh Yagoda

| Genrikh Grigoryevich Yagoda | |

|---|---|

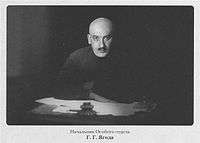

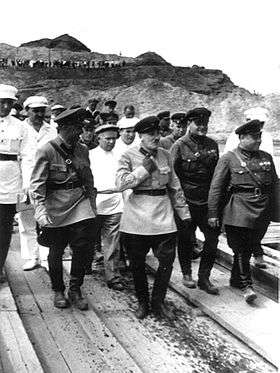

Genrikh Grigoryevich Yagoda at the podium in 1936 | |

| People's Commissar for Internal Affairs (NKVD) | |

|

In office 10 July 1934 – 26 September 1936 | |

| Preceded by | Vyacheslav Menzhinsky |

| Succeeded by | Nikolai Yezhov |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Yenokh Gershevich Iyeguda 7 November 1891 Rybinsk, Russian Empire |

| Died |

15 March 1938 (aged 46) Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Nationality | Soviet |

| Political party | Communist Party of the Soviet Union |

| Spouse(s) | Ida Leonidovna Averbach |

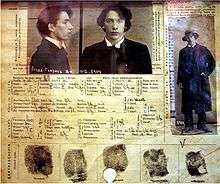

Genrikh Grigoryevich Yagoda (7 November 1891 – 15 March 1938), born Yenokh Gershevich Iyeguda was a secret police official who served as director of the NKVD, the Soviet Union's security and intelligence agency, from 1934 to 1936. Appointed by Joseph Stalin, Yagoda supervised the arrest, show trial, and execution of the Old Bolsheviks Lev Kamenev and Grigory Zinoviev, climactic events of the Great Purge. Yagoda supervised the construction of the White Sea–Baltic Canal with Naftaly Frenkel, using penal labor from the GULAG system, during which many laborers died.

Like many Soviet NKVD officers who conducted political repression, Yagoda himself became ultimately a victim of the Purge. He was demoted from the directorship of the NKVD in favor of Nikolai Yezhov in 1936 and arrested in 1937. Charged with the crimes of wrecking, espionage, Trotskyism and conspiracy, Yagoda was a defendant at the Trial of the Twenty-One, the last of the major Soviet show trials of the 1930s. Following his confession at the trial, Yagoda was found guilty and shot.

Early life

Yagoda was born in Rybinsk into a Jewish family. The son of a jeweller, trained as a statistician, who worked as a chemist's assistant,[1] he claimed that he was an active revolutionary from the age of 14, when he worked as a compositor on an underground printing press in Nizhni-Novgorod, and that at the age of 15 he was a member of a fighting squad in the Sormovo district of Nizhni-Novgorod, during the violent suppression of the 1905 revolution. One of his brothers was killed during the fighting in Sormovo; the other was shot for taking part in a mutiny in a regiment during the war with Germany. He said he joined the Bolsheviks in Nizhni-Novgorod at the age of 16 or 17, and was arrested and sent into exile in 1911.[2] Before his arrest, he married Ida Averbakh, one of whose uncles, Yakov Sverdlov, was a prominent Bolshevik, and another, Zinovy Peshkov, was the adopted son of the writer Maxim Gorky. In 1913, he moved to St Petersburg to work at the Putilov steel works. After the outbreak of war, he joined the army, and was wounded in action.[3]

There is another version of his early career, told in the memoirs of the former NKVD officer Aleksandr M. Orlov, who alleged that Yagoda invented his early revolutionary career and did not join the Bolsheviks until 1917, and that his deputy Mikhail Trilisser was dismissed from the service for trying to expose the lie.[4] It can be assumed that this was gossip put around by Yagoda's successors after his fall from power.

Political career

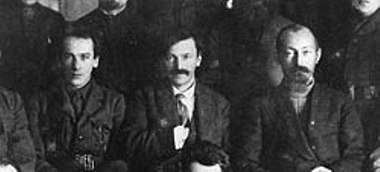

After the October Revolution of 1917, Yagoda rose rapidly through the ranks of the Cheka (the predecessor of the OGPU and NKVD) to become the second deputy of Felix Dzerzhinsky, the head of the Cheka, in September 1923. After Dzerzhinsky's appointment as chairman of the Supreme Council of National Economy in January 1924, Yagoda became the real manager of the State Political Directorate (OGPU), as the deputy chairman Vyacheslav Menzhinsky had little authority because of his serious illness. In 1924, he joined the USSR's head of government, Alexei Rykov on a ship tour of the Volga. An American journalist who was allowed to join them on the trip described Yagoda as "a spare, slightly-tanned, trim looking, youngish officer" adding that it was "difficult to associate terror with the affable and modest person".[5] By contrast, the chemist Vladimir Ipatieff met Yagoda briefly in Moscow in 1918 and thought that "it was unusual for a young men in his early twenties to be so unpleasant. I felt then that it would be unlucky for me or anyone else ever to fall into his hands." When he saw him again in 1927, "his appearance had changed considerably: he had grown fatter and looked much older and very dignified and important."[6]

Though Yagoda appears to have known Joseph Stalin since 1918, when they were both stationed in Tsaritsyn during the civil war, "he was never Stalin's man"[7] When Stalin ordered that the Soviet Union's entire rural population were to be forced onto collective farms, Yagoda is reputed to have sympathised with Bukharin and Rykov, his opponents on the right of the communist party. Nikolai Bukharin claimed in a leaked private conversation in July 1928 that "Yagoda and Trilisser are with us", but once it became apparent that the right was losing the power struggle, Yagoda switched allegiance. In the contemptuous opinion of Bukharin's widow, Anna Larina, Yagoda "traded his personal views for the sake of his career" and degenerated into a "criminal" and a "miserable coward".[8]

Yagoda continued to be effective head of the OGPU until July 1931, when the little known Old Bolshevik Ivan Akulov was appointed First Deputy Chairman, and Yagoda was demoted to the post of Second Deputy. Akulov was dismissed and Yagoda reinstated in October 1932, After Yagoda's fall, one of his former colleagues confessed: "We met Akulov with violent hostility...the entire party organisation in the OGPU was devoted to sabotaging Akulov."[9] Stalin must have agreed to his reinstatement with ill grace, because four years later he accused the OGPU/NKVD of being "four years behind" in rooting out the supposed Trotskyite anti-Soviet conspiracy, although Yagoda had been complicit in the execution of one of Trotsky's sympathisers, Yakov Blumkin, and in sending others to the GULAG, the system of forced labour created under his supervision.

As deputy head of the OGPU, Yagoda organized the building of the White Sea–Baltic Canal using forced labor at breakneck speed between 1931 and 1933 at the cost of huge casualties.[10] For his contribution to the canal's construction he was later awarded the Order of Lenin.[11] The construction of the Moscow-Volga Canal was started under his watch, but only completed after his fall by his successor Nikolai Yezhov.[12]

Yagoda supervised the deportations, confiscations, mass arrests and executions that accompanied the forced collectivisation, and was one of the people responsible for the Holodomor, which resulted in the deaths of at least 7.5 million people.[13][14] In March 1934, he was rewarded by being made a member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

Yagoda had founded a secret poison laboratory of OGPU that was at disposal of Stalin. One of the victims became his own NKVD boss, Vyacheslav Menzhinsky. He was slowly poisoned during two weeks by two assistants of Yagoda[15] Menzhinsky's death was followed one day later by death of Max Peshkov, the son of Maxim Gorky, the doyen of Soviet literature. Yagoda had been cultivating Gorky as a potentially useful contact since 1928, and employed Gorky's secretary, Pyotr Kryuchkov, as a spy. "Whenever Gorky met Stalin or other members of the Politburo, Yagoda would visit Kryuchkov's flat afterward, demanding a full account of what had been said. He took to visiting public baths with Kryuchkov. One day in 1932, Yagoda handed his valuable spy $4,000 to buy a car."[16] He had developed an obsession with Max Peshkov's wife, Timoshka, and visited her daily when she was newly widowed, though her mother denied that they were ever lovers.[17] According to Arkady Vaksberg and other researchers, Yagoda poisoned Maksim Gorky and his son on the orders from Joseph Stalin.[18]

NKVD Chief

On 10 July 1934, two months after Menzhinsky's death, Joseph Stalin appointed Yagoda People's Commissar for Internal Affairs, a position that included the oversight of both the regular and the secret police, the NKVD. Yagoda worked closely with Andrei Vyshinsky in organizing the first Moscow Show Trial, which resulted in the prosecution and subsequent execution of former Soviet politicians Grigory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev in August 1936 as part of Stalin's Great Purge. The Red Army high command was not spared and its ranks were thinned by Yagoda, as a precursor to the later and more extensive purge in the Russian military. More than a quarter of a million people were arrested during the 1934–1935 period; the GULAG system was vastly expanded under his stewardship, and penal labor became a major developmental resource in the Soviet economy.

Stalin became increasingly disillusioned with Yagoda's performance. In the middle of 1936, Stalin received a report from Yagoda detailing the unfavorable public reaction abroad to the show trials and the growing sympathy among the Soviet population for the executed defendants. The report enraged Stalin, interpreting it as Yagoda's advice to stop the show trials and in particular to abandon the planned purge of Mikhail Tukhachevsky, Marshal of the Soviet Union and the former commander in chief of the Red Army. Stalin was already unhappy with Yagoda's services, mostly due to the mismanagement of Kirov's assassination and his failure to fabricate "proofs" of ties between Kamenev and Zinoviev and the Okhrana (the tsarist security organization).[19] As one Soviet official put it, "The Boss forgets nothing."[20]

On 25 September 1936, Stalin sent a telegram (co-signed by Andrei Zhdanov) to the members of the Politburo. The telegram read:

"We consider it absolutely necessary and urgent that Comrade Yezhov be appointed to head the People's Commissariat of Internal Affairs. Yagoda has obviously proved unequal to the task of exposing the Trotskyite-Zinovievite bloc. The GPU was four years late in this matter. All party heads and the most of the NKVD agents in the region are talking about this."[21]

A day later, he was replaced by Yezhov, who managed the main purges during 1937–1938. Yagoda was demoted to the post of People's Commissar for Post and Telegraph.

Arrest, trial, and execution

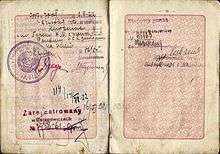

In March 1937, Yagoda was arrested on Stalin's orders. Yezhov announced Yagoda's arrest for diamond smuggling, corruption, and working as a German agent since joining the party in 1917. Yezhov even blamed Yagoda of an attempt to assassinate him by sprinkling mercury around his office. He was accused of poisoning Maxim Gorky and his son. It was discovered that Yagoda's two Moscow apartments and his dacha contained 3,904 pornographic photos, 11 pornographic films, 165 pornographically carved pipes, one dildo, and the two bullets that killed Zinoviev and Kamenev.[22] Yezhov took over the apartments. He had spent four million rubles decorating his three homes, boasting that his garden had "2,000 orchids and roses."[23]

Yagoda was found guilty of treason and conspiracy against the Soviet government at the Trial of the Twenty-One in March 1938. He denied he was a spy, but admitted most other charges.[24] Solzhenitsyn describes Yagoda as expecting clemency from Stalin after the show trial: "Just as though Stalin had been sitting right there in the hall, Yagoda confidently and insistently begged him directly for mercy: 'I appeal to you! For you I built two great canals!' And a witness reports that at just that moment a match flared in the shadows behind a window on the second floor of the hall, apparently behind a muslin curtain, and, while it lasted, the outline of a pipe could be seen."[25] [26]

Yagoda was summarily shot soon after the trial.[27] His wife Ida Averbakh was executed in 1938. His sister, Lilya, was arrested on 7 May 1937, and shot on 16 July.[28] His brother-in-law, Leopold Averbakh, was shot in August. In 1988, on the 50th anniversary of the trial, the Soviet authorities belatedly cleared all of the other 20 defendants of any criminal offence, admitting that the entire trial was built on false confessions. Yagoda was the only defendant not to be posthumously rehabilitated.

Honours and awards

Notes

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Genrikh Yagoda. |

- ↑ Montefiore, Simon Sebag (2004). Stalin, The Court of the Red Tsar. London: Phoenix. p. 98. ISBN 0 75381 766 7.

- ↑ See Yagoda's last plea at his trial in (1938). The Case of the Anti Soviet Bloc of Rights and Trotskyites, Verbatim Report. Moscow: People's Commissariat of Justice of the U.S.S.R. p. 784.

- ↑ Бажанов, Борис; Кривицкий, Вальтер; Орлов, Александр (2014). Ягода. Смерть главного чекиста (сборник). ISBN 978-5-457-26136-5.

- ↑ Orlov, Alexander. The Secret History of Stalin's Crimes.

- ↑ Reswick, William (1952). I Dreamt Revolution. Chicago: Henry Regnery Company. p. 85.

- ↑ Ipatieff, Vladimir (1946). The Life of a Chemist: Memoirs of Vladimir Ipatieff. Stanford, Ca: Stanford University Press.

- ↑ Montefiore, Simon Sebag (2004). Stalin, The Court of the Red Tsar. London: Phoenix. p. 98. ISBN 0 75381 766 7.

- ↑ Larina, Anna (1993). This I Cannot Forget. London: Pandora. pp. 100–101. ISBN 0 04 440887 0.

- ↑ Krivitsly, W.G. (1940). I Was Stalin's Agent. London: The Right Book Club. p. 170.

- ↑ Gulag, The Storm projects - The White Sea Canal, Gulag.eu. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- ↑ "Russia: Canal Heroes", Time Magazine; 14 August 1933. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- ↑ "Russia: Stalin's Mercy"; Time Magazine; 26 July 1937. Retrieved on 28 August 2011.

- ↑ "Seven million died in the 'forgotten' holocaust - Eric Margolis". www.ukemonde.com. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ↑ Agnieszka Bieńczyk-Missala, Sławomir Dębski (2010). Rafał Lemkin - Holodomor: the Ukrainian holocaust. Polski Instytut Spraw Miedzynarodowyc. p. 225

- ↑ The Secret File of Joseph Stalin: A Hidden Life by Roman Brackman, Routledge, 2004, p.204-205

- ↑ McSmith, Andy (2015). Fear and the Muse Kept Watch, The Russian Masters - from Akhmatov and Pasternak to Shostakovich and Eisenstein - Under Stalin. New York: The New Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-59558-056-6.

- ↑ McSmith. Fear and the Muse Kept Watch. p. 92.

- ↑ Arkady Vaksberg, The Murder of Maxim Gorky: A Secret Execution, 2006, Enigma Books, ISBN 1929631626

- ↑ Brackman, Roman., The Secret File of Joseph Stalin: A Hidden Life, London: Frank Cass Publishers (2001), p. 231

- ↑ Barmine, Alexander, One Who Survived, New York: G.P. Putnam (1945), pp. 295-296

- ↑ Medvedev, Roy. Let History Judge, New York (1971), p. 174

- ↑ Montefiore 2007, p. 195.

- ↑ Montefiore 2007, p. 85.

- ↑ Report of Court Proceedings in the Case of the Anti-Soviet 'Bloc of Rights and Trotskyites'. Moscow: People's Commissariat of Justice of the USSR. 1938. p. 573.

- ↑ See Aleksandr I. Solzhenitsyn. The Gulag Archipelago Vol I–II, Harper & Row, 1973, ISBN 0-06-013914-5

- ↑ Solzhenitsyn, Aleksandr I. (30 December 1973). "'The Gulag Archipelago, 1918–1956' Solzhenitsyn on Purge Trials of the 30's". Retrieved 1 April 2018 – via NYTimes.com.

- ↑ "Лаврентия Берию в 1953 году расстрелял лично советский маршал". Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ↑ The final photograph of Lilya Genrikh, taken before her execution is in King, David (2003). Ordinary Citizens, the Victims of Stalin. London: Francis Boutle. p. 142. ISBN 1 903427 150.

Bibliography

- Kotkin, Stephen (2014). Stalin: Volume I: Paradoxes of Power, 1878-1928. Penguin Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-698-17010-0.

- Montefiore, Simon Sebag (2007). Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-42793-9.

- Rayfield, Donald: Stalin und seine Henker. 2004

- Runes, Dagobert D.: Despotism, a pictorial history of tyranny. Philosophical Library 1963

- Н. В. Петров, К. В. Скоркин (N. W. Petrow, K.W. Skorkin): Кто руководил НКВД, 1934–1941 – Справочник. (Wer hatte die Regie im NKWD, 1934 bis 1941 – Verzeichnis); Swenja-Verlag 1999, ISBN 5-7870-0032-3 online

- А.Л. Литвин (A. L. Litwin): От анархо-коммунизма к ГУЛАГу: к биографии Генриха Ягоды (Über den Anarchokommunismus im Gulag: Mit einer Biografie von Genrich Jagoda) in 1917 год в судьбах России и мира. Октябрьская революция. (Das Jahr 1917 und die Schicksale Russlands und der Welt) S. 299–314, Institut für russische Geschichte РАН, Moskau 1998, ISBN 5805500078.