Brooks Sports

|

| |

| Subsidiary of Berkshire Hathaway | |

| Industry | Sports equipment |

| Founded | 1914 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Founder | John Brooks Goldenberg |

| Headquarters | Seattle, Washington, United States |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people | Jim Weber (CEO) |

| Products | Athletic shoes, Clothing |

Number of employees | 1000 |

| Parent | Berkshire Hathaway |

| Website |

www |

Brooks Sports, Inc., also known as Brooks Running, is an American company that designs and markets high-performance men's and women's running shoes, clothing, and accessories. Headquartered in Seattle, Washington, Brooks products are available in 60 countries worldwide. It is a subsidiary of Berkshire Hathaway.[1][2][3]

Brooks, founded in 1914, originally manufactured shoes for a broad range of sports. "White hot" in the mid-70s, the company faltered in the latter part of the decade, and filed for bankruptcy protection in 1981.[1][4] In 2001, the product line was cut by more than 50% to focus the brand solely on running, and its concentration on performance technology was increased. Brooks Running became the top selling brand in the specialty running shoe market in 2011,[5][6] and remained so through 2017 with a 25% market share.[7]

Brooks shoes have been named "Best Running Shoe" by publications including Runner's World[8] and Sports Illustrated.[9] The company has been recognized for environmental sustainability programs and technical innovation.[10][11]

History

Early history: Founding, Bruxshu Gymnasium Shoes, Carmen Manufacturing

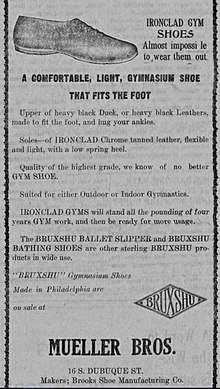

Brooks Sports, Inc. was founded in 1914 by John Brooks Goldenberg, following his purchase of the Quaker Shoe Company, a manufacturer of bathing shoes and ballet slippers.[10] Based in Philadelphia, it operated as a partnership between John Goldenberg and his brother, Michael. By 1920, Quaker Shoes had been renamed Brooks Shoe Manufacturing Co., Inc., and its shoes were sold under the brand name Bruxshu. In addition to bathing shoes and ballet slippers, it sold a gymnasium shoe, Ironclad Gyms. Early advertising emphasized fit, construction, and durability; the Ironclad was "a comfortable, light, gymnasium shoe that fits the foot" with soles made of "chrome tanned leather, flexible and light, with a low spring heel" that would withstand "four years gym work, and then be ready for more usage." [12] The company's innovations included the 1938 introduction of orthopedic shoes for children, Pedicraft,[13] and rubber brakes for roller skates (then known as "quick stops"), patented in 1944.[14]

In 1938, the Goldenbergs bought the Carmen Shoe Manufacturing Company in Hanover, Pennsylvania. Until 1957 a better grade leather was purchased, cut, stitched and fit in Philadelphia, while the same procedure in Hanover used lower grade materials. Both shoes were sold in Philadelphia under the Brooks name, and ranged from inexpensive to high-priced.[15]

In 1956, after a series of operational changes, John notified his brother that he would not renew their partnership agreement, and Michael discussed expanding Carmen with his nephew, John's son Barton. In 1957, following the dissolution of the partnership, the existence of Brooks Shoe Manufacturing Company was terminated, and Michael and Barton each acquired 50% of Carmen. In 1958, Michael purchased Barton's interest in the company, and as the sole owner, he renamed Carmen the Brooks Manufacturing Company.[15]

1970s: Introduction of EVA, the Vanguard, Runner's World #1 running shoe

In 1975, Brooks worked with elite runners, including Marty Liquori, a former Olympian, to design a running shoe. The collaboration produced the Villanova, Brook’s first high-performance running shoe.[16] It was the first running shoe to use EVA, an air-infused foam that was quickly adopted by other athletic brands. Brooks followed the Villanova with The Vantage, a running shoe constructed with a wedge to address overpronation. In 1977, based on newly developed measurements of cushioning, flexibility, and durability, the Vantage was ranked at #1 in the annual Runner's World running guide.[17] Runners embraced Brooks' technology, and the demand "exploded." Towards the end of the decade Brooks was among the top three selling brands in the US.[18]

1980s: Bankruptcy, the Chariot, Brooks for Women

In 1980, as a result of production issues with Brooks' manufacturing facility in Puerto Rico, defective shoes began to arrive at sporting goods stores. Nearly 30 percent of the shoes were returned, and Brooks scrapped 50,000 pairs. The company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, and was purchased at auction by footwear manufacturer Wolverine World Wide in 1981.[4][18]

In 1982, stability became the top priority for runners, and Brooks introduced the Chariot, a medial post shoe that featured an angled wedge of harder-density foam in the midsole. Thicker on the inside of the shoe and tapered toward the outside, the Chariot represented a “sea change” in running-shoe design.[17] In 1987, with Brooks for Women, it launched an anatomically adjusted line of shoes designed for women.[10]

1990s: The Beast, Adrenaline, ownership changes, apparel, Run Happy

In 1992, Brooks launched the Beast, a motion control shoe that integrated diagonal rollbar technology. In 1994, the Adrenaline GTS—an abbreviation for go-to shoe—was released. With a firmer midsole density, the Adrenaline GTS was built on a semi-curve, an accommodation for runners with a high arch and wide forefoot. The Beast became a best seller, and the Adrenaline GTS went on to become one of the best-selling running shoes of all time.[5][19]

Wolverine moved Brooks away from the niche running market to a generalist athletic brand. The "class to mass" strategy was unsuccessful, and Brooks was sold to Norwegian private equity company The Rokke Group for $21 million in 1993. Brooks moved to Rokke's Seattle location following its acquisition. In 1998, Rokke sold a majority interest in Brooks to J.H. Whitney & Co., a Connecticut private equity firm.[20]

Brooks introduced a full-line of technical running and fitness apparel for women and men in the spring of 1997. It also expanded into the walking category with the introduction of performance walking shoes.[21]

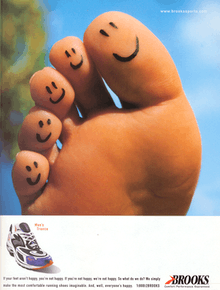

Brooks' Run Happy tag line first appeared in print advertising in 1999.[4] Rather than depicting running as a grueling pursuit, as competitive brands did, Run Happy was based on the idea that runners love running, and suggested that Brooks products allowed "runners to have the running experience they were looking for."[22][16]

2000s: Jim Weber, Berkshire Hathaway, BioMoGo

In 2001, Jim Weber, a former Brooks board member, was named president and CEO of the company. At the time, the company's market share was low, and bankruptcy had again become a concern. Weber cut lower-priced footwear from the Brooks product line, added an on-site lab and staff engineers, and focused the company on technical-performance running shoes.[23] As the brand was rebuilt, its annual revenue fell to $20 million. Three years later, it was $69 million.[20]

Brooks was acquired by Russell Athletic in 2004. In 2006, Russell was purchased by Fruit of the Loom and Brooks became a subsidiary of Fruit of the Loom's parent company, Berkshire Hathaway. It became an independent subsidiary of Berkshire Hathaway in 2011.[20]

In the mid-2000s, Brooks introduced High Performance Green Rubber, a material it developed for outsoles that used sand rather than petrolium.[24] It subsequently developed BioMoGo, the first biodegradable mid-sole for running shoes.[11] It used a non-toxic, natural additive that increased the rate of biodegradation by encouraging microbes in the soil to break the material down into nutrients that could be used by plants and animals, biodegrading approximately 20 times faster than traditional soles. By using BioMoGo, Brooks estimated that it would cut more than 30 million pounds of landfill waste over a 20-year period. The BioMoGo technology was open source.[25]

2010s: DNA, $500 million milestone, Brooks Heritage, 2017 awards, FitStation

Brooks DNA (and later Super DNA) was released in 2013. It provided customized cushioning, and adapted to the user's gender, weight and pace. Engineered from non-Newtonian liquid, it was another of Brooks' technological "firsts."[26]

In 2011, Brooks became the leading running shoe in the specialty market. On its 100-year anniversary, with a 29% market share, Brooks revenue hit $500 million. Weber stated that based on the company's year-over-year growth, investments from Berkshire Hathaway and the support of its CEO, Warren Buffett,[20] Brooks would become a billion dollar brand.[1][2]

The Brooks Heritage Collection was launched in 2016, returning the Vanguard, the Chariot, and the Beast to the market. Only the technology was updated; the details of the original shoes, including the colorways, were replicated.[27]

Brooks introduced the first customized performance running shoe based on personal biomechanics in the United States in December 2017. An instore station that combines 3D foot scanning with gait analysis and pressure mapping, it was developed in partnership with HP and Superfeet.[28]

In 2017, Brooks shoes were named Best Running Shoe (The Glycerine and the Launch, Sports Illustrated);[8][29] Editor's Top Choice (The Adrenaline GTS 18, Runner's World);[9] and Ten Best Running Shoes (The Levitate, Men's Fitness).[30]

Sustainability and social responsibility

The Brooks Running Responsibly Program measures sustainability based on five criteria: community, fair labor, product design and materials, manufacturing, and footprint.[24] In 2014, the company partnered with Bluesign Technologies (stylized as bluesign technologies) to evaluate, manage, and eliminate priority chemicals used in the process of manufacturing apparel. Manufacturers that become Bluesign system partners are required to establish management systems for improving resource productivity, consumer safety, water emissions, air emissions, and occupational health and safety. Brooks is also a member of the Sustainable Apparel Coalition, a global trade organization that works to reduce the environmental and social impact of apparel and footwear products.[31] Wherever possible, Brooks uses recycled materials, including in its shoeboxes, laces fabrics, hangtags and packaging. With the exception of the Brooks Heritage collection, its products are vegan.[24][32]

Built in 2014, the Brooks headquarters meet the environmental standards of Seattle's "Deep Green" pilot program. The building captures and reuses at least 50 percent of storm water on the site and uses 75 percent less energy than a typical commercial building in the city.[6] As of 2016, it was "one of the greenest buildings in the world."[33]

Brooks provides paid time annually to employees to volunteer for community organizations. Among other causes, Brooks employees have supported ConservationNEXT's Seattle Backyard Collective, Habitat for Humanity, Northwest Harvest, the Seattle Ronald McDonald House and the 2018 Special Olympic Games. "Run B'Cause" product donation grants are given annually to organizations who support a "healthier, Run Happier world."[34][35]

It was announced in June 2017 that Brooks Running would partner with the 2018 Special Olympics USA Games to create limited-edition co-branded running shoes and apparel, with a portion of the proceeds benefiting the games, and provide free running shoes to athletes participating in the Special Olympics Healthy Athletes Fit Feet program, which offers athletes free podiatric screenings.[35]

Sponsorship

Team sponsorships

- Hansons-Brooks

- Brooks Beasts Track Club

- Brooks Mavericks

Sponsored athletes (partial list)

References

- 1 2 3 Tracy, Abigail (April 24, 2014). "How Brooks Reinvented Its Brand". Inc. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- 1 2 Thomas, Lauren (October 30, 2017). "Brooks Running sees double-digit sales growth despite unpredictability of sports retail". CNBC. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ↑ Koopmans, Kelley (February 23, 2017). "How Brooks Running came back from the edge". KOMO News. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- 1 2 3 Garnick, Coral (June 19, 2014). "Brooks Sports running strong at 100". Seattle Times. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- 1 2 Karlson, Dana (January 21, 2015). "Brooks Sprints Into 2015, Holds Top Spot with Runners". Footwear News. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- 1 2 Max, Sarah (July 29, 2014). "Brooks Sports Moves New Home Closer to Trails". New York Times. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- ↑ Wahba, Phil (February 1, 2018). "A Kindred Sole". Fortune (Print edition): 30. ISSN 0015-8259.

- 1 2 Editors (April 4, 2017). "Best Women's Running Shoes". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- 1 2 Editors (November 17, 2017). "Best Winter Running Shoes". Runner's World. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- 1 2 3 FN Staff (May 12, 2014). "Milestone: Brooks Looks Back at 100 Years". Footwear News. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- 1 2 Schwartz, Ariel (June 29, 2009). "Brooks Designs a Sustainable Running Shoe From the Bottom Up". Fast Company. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ↑ "Ironclad Gym Advertisement" (PDF). Daily Iowan. February 25, 1920. p. 5. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- ↑ "Column". Frederick News. September 29, 1966. p. 14. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ↑ "US patent US2343007". US Patent Office (Via Google), 1944. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- 1 2 "United Shoe Workers of America vs. Brooks vs. Brooks Manufacturing Co". justia.com. US District Court for Eastern Pennsylvania. May 2, 1960. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- 1 2 Terjesen, S. and, Argue, E. (2001). "Run Happy: Entrepreneurship at Brooks". International Journal of Sports Management and Marketing. 7 (1/2): 133–139. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- 1 2 Beverly, Jonathan (November 18, 2016). "50 Years of (Mostly) Fantastic Footwear Innovation". Runners World. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- 1 2 Gupta, Hamanee (June 21, 1994). "If the Shoe Fits: Firm Seeks Bigger Foothold In Market". Seattle Times. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- ↑ RW staff (September 10, 2013). "Wayback Wonders". Runner's World. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Cunningham, Lawrence A. (October 21, 2014). Berkshire Beyond Buffett: The Enduring Value of Values. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 154, 155. ISBN 9780231170048. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- ↑ "Apparel World: Companies". Apparel International: The Journal of the Clothing and Footwear Institute. 28. 1997.

- ↑ Elliot, Stuart (January 27, 2014). "New Running Shoe Line Says, 'Come Fly With Me'". New York Times. Retrieved December 23, 2017.

- ↑ Wahba, Bill (October 21, 2014). "How Buffett's Brooks Running plans to become a $1 billion brand". Fortune. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- 1 2 3 Orlovi, Orlovic (June 27, 2016). "URBANMEISTERS SELECTS THEIR FAVORITE BRAND". Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ↑ Staff (June 10, 2009). "Brooks' BioMoGo Midsoles – a lighter impact". Alternative Consumer. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ↑ Jones, Riley (June 4, 2013). "Know Your Tech: Brooks DNA". Complex. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ↑ Forester, Pete (October 21, 2016). "The Heritage Sneaker Brand You Need on Your Radar". Esquire. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ↑ Ritterbeck, Molly (December 5, 2017). "First Look: FitStation Powered by HP and Brooks Run Signature". Runner's World. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ↑ SI Staff (March 14, 2017). "The Best Men's Running Shoes 2017". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ↑ Staff (September 21, 2017). "The 10 Best Running Shoes". Men's Fitness. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ↑ "Members". appparelcoalition.org. Sustainable Apparel Coalition. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ↑ "CASE STUDY: HOW BROOKS SPORTS INC. IS REDUCING ITS FOOTPRINT ONE SHOE BOX AT A TIME". Outdoor Industry Organization. June 3, 2012. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ↑ Levy, Nat (September 15, 2016). "Brooks Running's headquarters is officially one of the greenest buildings in the world". Geek Wire. Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- ↑ "2016 Responsibility Report" (PDF). brooksrunning.com. Brooks Running. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- 1 2 Staff (June 17, 2017). "Brooks Announces Partnership with Special Olympics". Running Competitor. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Brooks Sports. |