Br'er Rabbit

| Brer Rabbit | |

|---|---|

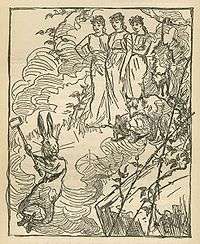

Br'er Rabbit and the Tar-Baby, drawing by E. W. Kemble from "The Tar-Baby", by Joel Chandler Harris, 1904 | |

| First appearance | 19th century |

| Created by | Traditional, Robert Roosevelt, Joel Chandler Harris, Alcée Fortier |

| Voiced by |

Johnny Lee (Song of the South and Mickey Mouse's Birthday Party[1]) James Baskett (The Laughing Place sequence in Song of the South[2]) Art Carney (Walt Disney's Song Parade from Disneyland[3]) Jess Harnell (Splash Mountain and modern Disney appearances) Nick Cannon (2006 adaptation) |

| Information | |

| Aliases | Riley, Compair Lapin |

| Species | Coney |

| Gender | Male |

| Occupation | Trickster |

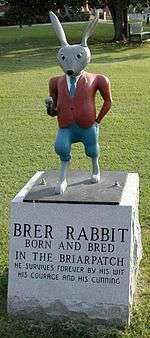

Br'er Rabbit /ˈbrɛər/ (Brother Rabbit), also spelled Bre'r Rabbit or Brer Rabbit or Bruh Rabbit, is a central figure as Uncle Remus tells stories of the Southern United States. Br'er Rabbit is a trickster who succeeds by his wits rather than by brawn, provoking authority figures and bending social mores as he sees fit. The Walt Disney Company later adapted this character for its 1946 animated motion picture Song of the South.

Tar-Baby story

In one tale, Br'er Fox constructs a doll out of a lump of tar and dresses it with some clothes. When Br'er Rabbit comes along he addresses the Tar-Baby amiably, but receives no response. Br'er Rabbit becomes offended by what he perceives as the Tar-Baby's lack of manners, punches it, and in doing so becomes stuck. The more Br'er Rabbit punches and kicks the tar "baby" out of rage, the more he gets stuck. When Br'er Fox reveals himself, the helpless but cunning Br'er Rabbit pleads, "please, Br'er Fox, don't fling me in dat brier-patch," prompting Fox to do exactly that. As rabbits are at home in thickets, the resourceful Br'er Rabbit uses the thorns and briers to escape. The story was originally published in Harper's Weekly by Robert Roosevelt; years later Joel Chandler Harris included his version of the tale in his Uncle Remus stories.

African origins

The Br'er Rabbit stories can be traced back to trickster figures in Africa, particularly the hare that figures prominently in the storytelling traditions in West, Central, and Southern Africa. These tales continue to be part of the traditional folklore of numerous peoples throughout those regions. In the Akan traditions of West Africa, the trickster is usually the spider Anansi, though the plots in his tales are often identical with those of stories of Br'er Rabbit.[4] However, Anansi does encounter a tricky rabbit called "Adanko" (Asante-Twi to mean "Hare") in some stories. The Jamaican character with the same name "Brer Rabbit", is an adaptation of the Ananse stories of the Akan people.[5]

Some scholars have suggested that in his American incarnation, Br'er Rabbit represented the enslaved Africans who used their wits to overcome adversity and to exact revenge on their adversaries, the white slave owners.[6] Though not always successful, the efforts of Br'er Rabbit made him a folk hero. However, the trickster is a multidimensional character. While he can be a hero, his amoral nature and his lack of any positive restraint can make him into a villain as well.[7]

For both Africans and African Americans, the animal trickster represents an extreme form of behavior that people may be forced to adopt in extreme circumstances in order to survive. The trickster is not to be admired in every situation. He is an example of what to do, but also an example of what not to do. The trickster's behavior can be summed up in the common African proverb: "It's trouble that makes the monkey chew on hot peppers." In other words, sometimes people must use extreme measures in extreme circumstances.[8] Several elements in the Brer Rabbit Tar Baby story (e.g., rabbit needing to be taught a lesson, punches and head butting the rabbit does, the stuck rabbit being swung around and around) are reminiscent of those found in a Zimbabwe-Botswana folktale.[9]

Folklorists in the late 19th century first documented evidence that the American versions of the stories originated among enslaved West Africans based on connections between Br'er Rabbit and Leuk, a rabbit trickster in Senegalese folklore.[7][10] The stories of Br'er Rabbit were written down by Robert Roosevelt, an uncle of US President Theodore Roosevelt. Theodore Roosevelt wrote in his autobiography about his aunt from the State of Georgia, that "She knew all the 'Br'er Rabbit' stories, and I was brought up on them. One of my uncles, Robert Roosevelt, was much struck with them, and took them down from her dictation, publishing them in Harper's, where they fell flat. This was a good many years before a genius arose who, in 'Uncle Remus', made the stories immortal."

These stories were popularized for the mainstream audience in the late 19th century by Joel Chandler Harris (1845–1908), who wrote down and published many such stories that had been passed down by oral tradition. Harris also attributed the birth name Riley to Br'er Rabbit. Harris heard these tales in Georgia. Very similar versions of the same stories were recorded independently at the same time by the folklorist Alcée Fortier in southern Louisiana, where the Rabbit character was known as Compair Lapin in Creole. Enid Blyton, the English writer of children's fiction, retold the stories for children.

Cherokee origins

Although Joel Chandler Harris collected materials for his famous series of books featuring the character Br'er Rabbit in the 1870s, the Br'er Rabbit cycle had been recorded earlier among the Cherokees: The "tar baby" story was printed in an 1845 edition of the Cherokee Advocate, the same year Joel Chandler Harris was born.[11]

Rabbit and Hare myths abound among Algonquin Indians in Eastern North America, particularly under the name Nanabozho. The Great Hare is generally worshipped among tribes in eastern Canada.

In "That the People Might Live: Native American Literatures and Native American Community" by Jace Weaver, the origins of Br'er Rabbit and other literature are discussed. To say that a story only originates from one culture and not another can only be true when a group of people exist in complete isolation from others. Although the Cherokee had lived in isolation from Europeans in the remote past, a substantial amount of interaction was to occur among North American tribes, Europeans, and those from the enslaved population during the 18th and 19th centuries. It is impossible to ascertain whether the Cherokee story independently predated the African American story.

In a Cherokee tale about the briar patch, "the fox and the wolf throw the trickster rabbit into a thicket from which the rabbit quickly escapes."[12] There was a "melding of the Cherokee rabbit-trickster ... into the culture of African slaves."[13]

In popular culture

Under Disney

- The 1946 Disney film Song of the South is a frame story based on two Br'er Rabbit stories, "The Laughing Place" and "The Tar Baby". The character of Br'er Rabbit was voiced by Johnny Lee in the film, and was portrayed as more of a "lovable trickster" than previous tales.[14] Disney comics starring that version of Br'er Rabbit have been produced since 1946.[15]

- Splash Mountain, a thrill ride at Magic Kingdom, Disneyland, and Disneyland Tokyo, is based on the above 1946 film's animated segments featuring Br'er Rabbit. Br'er Rabbit also appears at the Walt Disney Parks and Resorts for meet-and-greets, parades and shows. He also has a cameo appearance in Who Framed Roger Rabbit, and appears as one of the guests in House of Mouse. He also appears in the film Mickey's Magical Christmas: Snowed in at the House of Mouse, often seen hopping in the applauding crowd, as well as in the video game Kinect Disneyland Adventures. Starting with the first Splash Mountain Disney park attraction in 1989, Jess Harnell has provided the voice acting for Br'er Rabbit in all his modern Disney appearances since.

- An Uncle Remus and His Tales of Br'er Rabbit newspaper strip ran from October 14, 1946 through December 31, 1972.[16]

Non-Disney

- On April 21, 1972, astronaut John Young became the ninth person to step onto the Moon, and in his first words he stated, "I'm sure glad they got ol' Brer Rabbit, here, back in the briar patch where he belongs."[17]

- In 1975, the stories were retold for an adult audience in the cult animation film Coonskin, directed by Ralph Bakshi.

- In 1984, American composer Van Dyke Parks produced a children's album, Jump!, based on the Brer Rabbit Tales.

- 1998's Star Trek: Insurrection saw the Starship Enterprise enter a region of space called the Briar Patch. At some point during a battle with the Son'a, Commander Riker states that it is "time to use the Briar Patch the way Br'er Rabbit did".

- A direct-to-video film based on the stories, The Adventures of Brer Rabbit, was released in 2006.

See also

References

- ↑ "A Spin Special: Stan Freberg Records". Retrieved 2017-09-21.

- ↑ "The Song of the South Frequently Asked Questions". Retrieved 2017-09-22.

- ↑ "Walt Disney's Song Parade from Disneyland on Golden Records". Retrieved 2017-09-26.

- ↑ Opala, Joseph A. "Gullah Customs and Traditions". The Gullah: Rice, Slavery, and the Sierra Leone-American Connection. Archived from the original on 2006-05-17.

- ↑ "African_Ja_Charact". anansistories.com. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ↑ Levine, Lawrence (1977). Black Culture and Black Consciousness: Afro-American Folk Thought from Slavery to Freedom. Oxford University Press.

- 1 2 Arnold, Albert (1996). Monsters, Tricksters, and Sacred Cows: Animal Tales and American Identities. University of Virginia Press.

- ↑ "Brer Rabbit and Ananse Stories from Africa (article) by Peter E Adotey Addo on AuthorsDen". Authorsden.com. Retrieved July 3, 2010.

- ↑ Smith, Alexander McCall (1989). The Girl Who Married A Lion and Other Tales from Africa. Pantheon Books, NY. pp. 185–89.

- ↑ M'Baye, Babacar (2009). The Trickster Comes West: Pan-African Influence in Early Black Diasporan Narratives. Univ. Press of Mississippi.

- ↑ "Cherokee Tales and Disney Films Explored". Powersource.com. June 15, 1996. Archived from the original on May 24, 2011. Retrieved July 3, 2010.

- ↑ Latin American Indian literatures journal. Dept. of Foreign Languages at Geneva College. 6: 10. 1990. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ That the People Might Live: Native American Literatures and Native American Community, p. 4

- 1 2 Brasch, Walter M. (2000). Brer Rabbit, Uncle Remus, and the 'Cornfield Journalist': The Tale of Joel Chandler Harris. Mercer University Press. pp. 74, 275.

- ↑ "Brer Rabbit - I.N.D.U.C.K.S." coa.inducks.org. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ↑ "Disney’s “Uncle Remus” strips," Hogan's Alley #16, 2009

- ↑ "Back in the Briar Patch". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Br'er Rabbit. |

- Full text of Joel Chandler Harris from Project Gutenberg

- Brer Rabbit Stories at AmericanFolklore.net

- Robert Roosevelt's Brer Rabbit stories

- Theodore Roosevelt autobiography on Brer Rabbit and his Uncle

- Inducks' index of Disney comic stories featuring Br'er Rabbit

- Archived audio recording of an educational ArtsSmarts elementary school recording of "Brother Rabbit and Tar Baby"