Blaenavon

Blaenavon

| |

|---|---|

Blaenavon | |

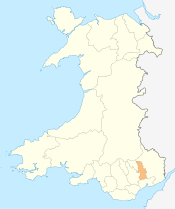

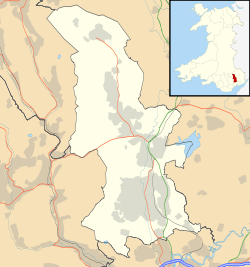

Blaenavon Blaenavon shown within Torfaen | |

| Area | 17.83 km2 (6.88 sq mi) [1] |

| Population | 6,055 (2011)[2] |

| • Density | 340/km2 (880/sq mi) |

| GSS code | W04000760 |

| OS grid reference | SO 255 095 |

| Community |

|

| Principal area | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Country | Wales |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | PONTYPOOL |

| Postcode district | NP4 |

| Dialling code | 01495 |

| Police | Gwent |

| Fire | South Wales |

| Ambulance | Welsh |

| EU Parliament | Wales |

| UK Parliament | |

| Welsh Assembly | |

Blaenavon (Welsh: Blaenafon) is a town and community in south eastern Wales, lying at the source of the Afon Lwyd north of Pontypool, within the boundaries of the historic county of Monmouthshire and the preserved county of Gwent. The town lies high on a hillside and has a population of 6,055. Blaenavon literally means "front of the river" or loosely "river's source" in the Welsh language. Parts of the town and surrounding country form the Blaenavon Industrial Landscape, inscribed as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 2000.

Blaenavon is a community represented by Blaenavon Town Council and electoral ward of Torfaen County Borough Council.

History

Blaenavon grew around an ironworks opened in 1788 by the West Midlands Industrialist, Thomas Hill (1736-1824), and his partners, Thomas Hopkins(d.1793) and Benjamin Pratt (1742-1794). The Three partners seized the opportunity to invest in the Blaenavon site, which they knew was rich in mineral resources. The businessmen invested some £40,000 into the iron works project and erected three blast furnaces. They combined their vast experience and founded a hugely successful iron works. Thomas Hopkins, through operating the Cannock Wood Forge in Rugeley, Staffordshire, was in contact with skilled and experienced ironworkers. He managed to persuade many of them to migrate to Blaenavon to help establish the new iron works. It is likely that the iron masters provided incentives to convince these workers and their families to relocate. Comfortable accommodation, for example, was provided for them at Stack Square, in the immediate vicinity of the works. It was absolutely essential that these skilled workers were brought to Blaenavon because they were required not only to help build and start the works but also to train new workers in the art of iron-making. It would have been useless to have an impressive iron works with no-one skilled enough to make the iron. In 1793, Thomas Hopkins died leaving his 25% share in the Company to his son Samuel Hopkins (1761-1815) .Benjamin Pratt died suddenly in May 1794, bequeathing all of his capital to his friend and colleague Thomas Hill. Thomas Hill continued to run the Blaenavon enterprise with his 32 year old nephew, Samuel Hopkins, who became residential manager of the ironworks.

Archdeacon William Coxe, in his Historical Tour of Monmouthshire tells us that in 1798 Hopkins was building ‘a comfortable and elegant mansion’ for himself. When the young Hopkins arrived in Blaenavon his first concern was to ensure that he had a fine home, but at the same time some of the poorer Blaenavon residents did not even have adequate housing. Hopkins had even ordered that the arches of a local viaduct be bricked up to provide make-shift accommodation for the surplus workforce. Hopkins’s Mansion, known as Ty-Mawr or Blaenavon House, was an expensive and elaborate home, a visible contrast to the homes inhabited by the workers. The 3 storey classically Georgian Mansion stood in an expansive parkland setting. Despite his ‘extravagance’ Samuel Hopkins was a very popular man in Blaenavon, who was seen as a father-figure by many of the local people. The historian Lewis Browning claimed that Hopkins made the effort to learn the name of every worker and treated the people of Blaenavon with respect. Samuel Hopkins and his uncle, Thomas Hill, both staunch Anglicans, took religious leadership in the community and were responsible for the creation of St. Peter’s Church in 1804. The gifting of the church to the parish was the earliest example of an industrialist family establishing an Anglican church in south Wales. Following Hopkins death in 1815, his sister Sarah Hopkins of Rugeley, who had inherited much money from her late brother, erected a school for the children of Blaenavon in his memory. The Blaenavon Endowed School was completed in 1816 initially had one hundred and twenty pupils and the first headmaster was Mr. John Caldwell. The educational initiative promoted by the Hopkins siblings provides one of the earliest examples of an industrialist family taking a leading role in the education of their workers’ children in Wales. In 1836 Robert William Kennard JP DL (1800–1870) formed the Blaenavon Coal and Iron Company in 1836, which subsequently bought the Blaenavon Ironworks.[4] There he employed his son, the noted civil engineer Thomas Kennard, and his cousin and the later photographer George Swan Nottage. Thomas Kennard took up residency at Ty-Mawr and set about extending it in 1836. Ty-Mawr remained in the ownership of The Blaenavon Coal and Iron Company and following the death of Kennard, was used by the Directors of the Blaenavon Company as a hunting lodge until 1924, when it became a hospital supported by the subscriptions of local people (an early form of NHS).

When the Hospital closed it became a nursing home and in 1995 a Grade 2 Listed Building. Left empty following its closure in 2006, badly vandalised and stripped of its lead work, slate Roof and original interiors, the building was placed on the At Risk register. The House was sold in 2017 and is currently undergoing restoration as a family home once again.

The Blaenavon Coal and Iron Company developed the Big Pit coalworks with adjoining steel works particularly rail manufacture, part of which since 1988 is the museum.[3][4] The steel-making and coal mining industries followed, boosting the town's population to over 20,000 at one time before 1890.[5] Following twenty years after the closure of the ironworks in 1900 the population has declined gradually at each ten-year census, including rapidly after closure of the coal mine in 1980; it had however already fallen to 8,451 in 1961. Part of this decline was not emigration but a decrease in birth rate.[6]

Features

Attractions in the town include the Big Pit National Coal Museum (an Anchor Point of ERIH, The European Route of Industrial Heritage), Blaenavon Ironworks,[7] the Pontypool and Blaenavon Railway, Blaenavon World Heritage Centre, Blaenavon Male Voice Choir, Blaenavon Town Band and many historical walks through Blaenavon's mountains.

The Pontypool and Blaenavon Railway is a scenic attraction rich in geological and historical interest. Blaenavon lost both of its passenger railway stations — Blaenavon High Level station closed in 1941; the last train from Blaenavon (Low Level) (namely to Newport via Pontypool Crane Street) ran in April 1962. Contrary to an oral tradition, the lower line had already been closed for more than a year before the anti-subsidy Beeching Axe took place. The lower lines passenger service was among many in Gwent (Monmouthshire) were Ministry of Transport de-classified papers reveal were axed due to rail congestion in the Newport area following the newly opened Llanwern steelworks.

Blaenavon Golf Club (now defunct) was founded in 1906. The club closed in 1937.[8]

Government, publishers and mainly Welsh writers sought in 2003 to attract more visitors by introducing Blaenavon as Wales' second "book town" (the first being Hay-on-Wye on the English border). However the project did not succeed.[9] This can be attributed to a combination of the town's remote location and the established competition from Hay. Many thriving community groups serve and improve the town, including Future Blaenavon, which has helped to create a community garden at the bottom of the town.

Time Team dig

The Channel 4 archaeology television programme Time Team came to Blaenavon during its February 2001 series to find "The Lost Viaduct" – "the world's first railway viaduct". This had been built in 1790, to be used by horse-drawn wagons to carry coal from the mines. The viaduct, estimated as about 40 metres long and 10 metres high about 25 years after being built, disappeared. No records exist of its demolition and the archaeologists found in the final day of the modestly funded excavation to uncover the top of the viaduct, the arched roof of which, under 12–15 metres of rubble and earth, was seemingly intact. For reasons of safety and preservation they dug no further.

Notable people

Notable Broadway and film actor E. E. Clive, award-winning mystery writer Dorothy Simpson, and international rugby union players Mark Taylor (Wales), Ken Jones (Wales and British Lions and also Olympic athlete), John Perkins (Wales), Chris Huish (Wales) Terry Cobner (Wales and British Lions) were all born in Blaenavon. Nicklaus Thomas-Symonds, elected MP for Torfaen in 2015, was brought up in the town.

Gallery of Blaenavon photos

Big Pit National Coal Museum

Big Pit National Coal Museum Rail manufactured in Blaenavon, seen in Sweden

Rail manufactured in Blaenavon, seen in Sweden Horeb Baptist church

Horeb Baptist church Blaenavon War Memorial and Workmen's Hall

Blaenavon War Memorial and Workmen's Hall- The Church in Wales church of St Peter

The Church in Wales church of St Paul

The Church in Wales church of St Paul

See also

References

- ↑ "2011 Census:Quick Statistics:Population Density for Blaenavon". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- ↑ "2011 Census:Key Statistics:Key Figures for Blaenavon". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ↑ Ironworks photo at geograph

- ↑ McCrum, Kirstie (7 September 2013). "Going Underground; Big Pit: National Coal Museum Is Celebrating Its 30th Anniversary as a Tourist Attraction and Museum". Western Mail. Retrieved 14 June 2016 – via Questia. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Workmen's Hall photo at geograph

- ↑ http://www.visionofbritain.org.uk/unit/10045757/cube/TOT_POP

- ↑ Blaenavon Ironworks

- ↑ “Blaenavon Golf Club”, “Golf’s Missing Links”.

- ↑ the Book Guide: Blaenafon - The Booktown Experiment Fails, 17 March 2006 Archived 23 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine.. Accessed 2 November 2012

- ↑ "Town Twinning". Torfaen County Borough Council. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Blaenavon. |

- Old photos of Blaenavon

- Welsh Coal Mines - all the pits, all the histories

- Blaenavon Town Council

- Time Team - The Lost Viaduct

- Aerial photograph of Blaenavon in 1999

- Blaenavon Local History Society website