Black mamba

| Black mamba snake | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Serpentes |

| Family: | Elapidae |

| Genus: | Dendroaspis |

| Species: | D. polylepis |

| Binomial name | |

| Dendroaspis polylepis | |

| |

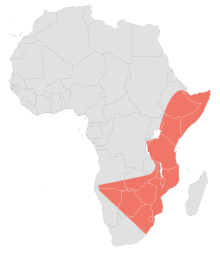

| Distribution range of black mamba | |

| Synonyms[3] | |

|

List

| |

The black mamba (Dendroaspis polylepis) is an extremely venomous snake of the family Elapidae, and native to parts of sub-Saharan Africa. First described by Albert Günther in 1864, it is the longest species of venomous snake indigenous to the African continent; mature specimens generally exceed 2 meters (6.6 ft) and commonly attain 3 meters (10 ft). Specimens of 4.3 to 4.5 meters (14.1 to 14.8 ft) have been reported. Its skin colour varies from grey to dark brown. Juvenile black mambas tend to be paler than adults and darken with age.

The black mamba inhabits savannah, woodlands, rocky slopes and, in some regions, dense forest. The black mamba is both terrestrial and arboreal. It is diurnal and is known to prey on hyrax, bushbabies and other small mammals, as well as birds. Over suitable surfaces, it is possibly the fastest species of snake, capable of at least 11 km/h (6.8 mph) over short distances. Adult mambas have few natural predators.

In a threat display, the mamba usually opens its inky-black mouth, spreads its narrow neck-flap and sometimes hisses. It is capable of striking at considerable range and may occasionally deliver a series of bites in rapid succession. Its venom is primarily composed of potent neurotoxins that may cause a fast onset of symptoms. Despite its reputation as formidable and highly aggressive, it usually attempts to flee from humans unless threatened or cornered. The black mamba is rated as least concern on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)'s Red List of Endangered species.

Taxonomy

Although the black mamba had been known to missionaries[4] and residents,[5] before 1860, the first formal description was made by German-British zoologist Albert Günther in 1864.[2][3] A single specimen was one of many snake species collected by Dr John Kirk, a naturalist who accompanied Dr David Livingstone on the Second Zambesi expedition.[6] The specific epithet polylepis is derived from the Ancient Greek poly (πολύ) meaning "many" and lepis (λεπίς) meaning "scale".[7] The term "mamba" is derived from the Zulu word "imamba".[8] A local Ngindo name in Tanzania is ndemalunyayo "grass-cutter" as it supposedly clips grass.[9]

In 1873, German naturalist Wilhelm Peters described Dendraspis Antinorii from a specimen in the museum of Genoa, which had been killed by Orazio Antinori in what is now northern Eritrea.[10] This was subsequently regarded as a subspecies,[3] and is no longer held to be distinct.[2] In 1896, Belgian-British zoologist George Albert Boulenger combined the species (Dendroaspis polylepis) as a whole with the eastern green mamba (Dendroaspis angusticeps),[11] a lumping diagnosis that remained in force until 1946, when South African herpetologist Vivian FitzSimons split them again into separate species.[12]

The black mamba is an elapid snake within the genus Dendroaspis. A 2016 genetic analysis showed that the black and eastern green mambas were each others' closest relatives, and more distantly related to Jameson's mamba.[13]

Description

The black mamba is a long, slender, cylindrical snake with a "coffin-shaped" head and a somewhat pronounced brow ridge and a medium-sized eye.[14][15] The adult snake's length typically ranges from 2–3 m (6 ft 7 in–9 ft 10 in) but specimens have grown to lengths of 4.3 to 4.5 m (14.1 to 14.8 ft).[12][15] It is the second longest venomous snake species, exceeded in length only by the king cobra.[16] The black mamba is a proteroglyphous snake, with fangs up to 6.5 mm (0.26 in) in length.[17] located at the front of the maxilla.[16] The tail of the species is long and thin, and is 17–25% of its body length.[14] Black mambas weigh about 1.6 kg (3.5 lb) on average.[18]

Specimens vary considerably in color; some may be olive, yellowish-brown, khaki or gunmetal, but are rarely black. Some individuals may a have a purplish glow to their scales. Occasionally they may display dark mottling towards the posterior, which may appear in the form of diagonal crossbands. They have greyish-white underbellies while the inside of the mouth is dark bluish-grey to nearly black. Mamba eyes are greyish brown to shades of black while the pupil is surrounded by silvery white or yellow color. Juvenile snakes are lighter in color than adults, typically grey or olive green in appearance, and get darker as they age.[17][12][14]

Scalation

The head, body and tail scalation of the black mamba:[15]

|

|

Distribution and habitat

_juvenile_(under_2m...)_on_top_of_a_tree_..._(30397328144).jpg)

The black mamba has a wide range within sub-Saharan Africa. Specifically, it has been observed in north east Democratic Republic of the Congo, south western Sudan to Ethiopia, Eritrea, Somalia, Kenya, eastern Uganda, Tanzania, Burundi, Rwanda, south to Mozambique, Swaziland, Malawi, Zambia, Zimbabwe and Botswana to KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa, and Namibia; then northeast across Angola to south eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo.[17][19]

The black mamba's distribution contains gaps within the Central African Republic, Chad, Nigeria and Mali. These gaps may lead physicians to misidentify black mamba bites and administer an inappropriate antivenom. In 1954 the black mamba was recorded in, in the Dakar region of Senegal. However, this observation, and a subsequent observation that identified a second specimen in the region in 1956, has not been confirmed and thus the snake's distribution in this area is inconclusive.[19]

The black mamba prefers moderately dry environments such as light woodland and scrub, rocky outcrops, and semi-arid savannah.[19] It also inhabits moist savanna and lowland forests.[15] It is not commonly found at altitudes above 1,000 metres (3,300 ft), although its distribution does include 1,800 metres (5,900 ft) in Kenya and 1,650 metres (5,410 ft) in Zambia.[19] It is rated as a species of least concern on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)'s Red List of Endangered species, based on its huge range across sub-Saharan Africa and no documented decline.[1]

Behaviour and ecology

The black mamba is both terrestrial and arboreal. It moves on the ground with its head and neck raised and typically uses termite mounds, abandoned burrows, rock crevices, tree cracks as shelter. It may share its lair with other snake species like the Egyptian cobra. Black mambas are diurnal and in South Africa, they are recorded to bask from 7–10 am and again from 2–4 pm. They may return to the same basking site daily.[15][14]

The black mamba is graceful but skittish and often unpredictable. It is agile and can move quickly.[17][15] When it senses a perceived threat, it retreats into brush or a hole.[15] In the wild, a black mamba seldom tolerates humans approaching more closely than about 40 meters.[15] When confronted it is likely to gape in a threat display, exposing its black mouth and flicking its tongue.[17] It also is likely to form a narrow hood by spreading its neck-flap. The threat display may be accompanied by hissing.[18][17][15]

During the threat display, any sudden movement by the intruder may provoke the mamba into a series of rapid strikes leading to severe envenomation.[15] Also, the size of the black mamba, plus its ability to raise its head well off the ground, enable it to launch as much as 40% of its body length upwards, so mamba bites in humans may occur on the upper body.[17][15] The black mamba's reputation for being ready to attack is exaggerated and usually is provoked by perceived threats, such as blocking its movements and ability to retreat, accidentally or otherwise.[17] The black mamba's reputed speed has also been exaggerated. It can slither at no more than 16 km/h (9.9 mph).[14]

Reproduction and lifespan

Black mambas breed from April to June.[12] During the mating season rival males may compete by wrestling. Opponents attempt to subdue each other by intertwining their bodies and wrestling with their necks. Some observers have mistaken this for courtship.[15][14] During mating, the male will slither over the dorsal side of the female while flicking his tongue. The female will signal she is ready to mate by lifting her tail and staying still. The male will then coil around the posterior end of the female and align this tail with hers ventrolaterally. Intermission may last longer than two hours and the pair would stay motionless apart from occasional spasms from the male.[12]

The black mamba is oviparous; the female laying 6–17 eggs in a clutch.[15] The eggs are oval-shaped and enlongated, measuring 60–80 mm (2.4–3.1 in) long and 30–36 mm (1.2–1.4 in) in diameter. When hatched, the young range from 40–60 cm (16–24 in) in length. They may grow quickly, reaching 2 m (6 ft 7 in) after their first year. Like the adults, juvenile mambas can be deadly.[15][17] The black mamba is recorded to live up to 11 years, possibly longer.[18]

Feeding

The black mamba usually goes hunting from a permanent lair, to which it will regularly return if there is no disturbance. It mostly preys on birds, particularly nestlings and feldglings, and small mammals like rodents, bats, hyraxes and bushbabies. They generally prefer warm-blooded prey but will consume other snakes. The black mamba does not typically hold onto prey after biting, instead releasing its quarry and waiting for it to succumb to paralysis and die. It has a potent digestive system and has been recorded to fully digest prey between eight and ten hours.[15][17][12][14]

There are few predators of adult mambas, aside from birds of prey. Young snakes have been recorded as prey of the Cape file snake.[12] Mongooses, which have some immunity to the venom, and are often quick enough to evade a bite, will sometimes tackle a black mamba for prey.[20][21]

Venom

The black mamba is popularly regarded as the most dangerous and feared snake in Africa.[22] However, attacks on humans by black mambas are rare, as they usually try to avoid confrontation, and their occurrence in highly populated areas is not very common compared with some other species.[23] Additionally, the ocellated carpet viper is responsible for more human fatalities due to snakebite than all other African species combined.[24] A survey of snakebites in South Africa from 1957 to 1963 recorded over 900 venomous snakebites, but only seven of these were confirmed black mamba bites, at a time when effective antivenom was not widely available. Out of more than 900 bites, only 21 ended in fatalities, including all seven black mamba bites.[25]

In 2015, the proteome (complete protein profile) was assessed and published, revealing 41 distinct proteins and one nucleoside.[26]

The black mamba's venom is composed of neurotoxins (dendrotoxin) and cardiotoxins as well as other toxins such as fasciculins.[27][28] In an experiment, the most abundant toxin found in black mamba venom was observed to be able to kill a mouse in as little as 4.5 minutes.[22] Based on the murine median lethal dose (LD50) values, the black mamba's toxicity from all published sources is as follows:

- (SC) subcutaneous (most applicable to real bites): 0.32 mg/kg,[29][30][31][32] 0.28 mg/kg.[29][24]

- (IV) intravenous: 0.25 mg/kg,[30][31] 0.011 mg/kg.[33]

- (IP) intraperitoneal: 0.30 mg/kg (average),[34] 0.941 mg/kg.[30]

This venom is extremely toxic. A bite from a black mamba can deliver about 100–120 mg of venom on average and the maximum dose recorded is 400 mg.[27] It is reported that before antivenom was widely available, the mortality rate from a bite was nearly 100%.[18] The bite of a black mamba can potentially cause collapse in humans within 45 minutes, or less.[35] Without effective antivenom therapy, death typically occurs in 7–15 hours.[27]

A bite from a black mamba causes initial neurological and neuromuscular symptoms that may commonly include headache and a metallic taste in the mouth, which may be accompanied by a triad of paresthesias, profuse perspiration and salivation.[36] Other symptoms may include ptosis and gradual bulbar palsy.[36] Localised pain or numbness around the bite site is common but not typically severe;[37] therefore, application of a tourniquet proximal to the bite site is feasible and may assist in slowing the onset of prominent neurotoxicity.[36] Without appropriate treatment, symptoms typically progress to more severe reactions such as tachydysrhythmias and neurogenic shock, leading to death by asphyxiation, cardiovascular collapse, or respiratory failure.[27][28][36]

Pharmaceutical applications

Peptides in black mamba venom have been found to be effective analgesics. These peptides, part of the 'three-finger' family of snake venom toxins (mambalgins), act as inhibitors for acid-sensing ion channels in the central and peripheral nervous system, causing a pain-inihibiting effect. While this effect can be as strong as that of morphine, mambalgins do not have a resistance to naloxone, suffer less from induced tolerance, and cause no respiratory distress.[38]

Reported bite cases

Danie Pienaar, now head of South African National Parks Scientific Services,[39] survived the bite of a black mamba without antivenom in 1998. Although no antivenom was administered, Pienaar was in a serious condition, despite the hospital physicians having declared it a "moderate" black mamba envenomation. At one point, Pienaar lapsed into a coma and his prognosis was declared "poor". Upon arrival at hospital Pienaar was immediately intubated, given supportive drug therapy, put on mechanical ventilation and placed on life support for three days, until the toxins were flushed out of his system. He was released from hospital on the fifth day. Pienaar believes he survived for several reasons. In an article in Kruger Park Times he said "Firstly, it was not my time to go." The article went on to state, "The fact that he stayed calm and moved slowly definitely helped. The tourniquet was also essential."[40]

In another case, 28-year-old British student Nathan Layton was bitten by a black mamba and died in March 2008. The black mamba had been found near a classroom at the Southern African Wildlife College in Hoedspruit, where Layton was training to be a safari guide. Layton was bitten by the snake on his index finger while it was being put into a jar, but he didn't realize he'd been bitten. He thought the snake had only brushed his hand. Approximately 30 minutes after being bitten Layton complained of blurred vision. He collapsed and died of a heart attack, nearly an hour after being bitten. Attempts to revive him failed, and he was pronounced dead at the scene.[41][42]

Treatment

Standard first aid treatment for any suspected bite from a poisonous snake is for a pressure bandage to the bite site, the victim to move as little as possible, and to be conveyed to a hospital or clinic, where they should be monitored for at least 24 hours. Tetanus toxoid is given, though the mainstay of treatment is the administration of the appropriate anitvenom.[43] Presently, there is a polyvalent antivenom produced by the South African Institute for Medical Research to treat black mamba bites from many localities,[44] and a new antivenom is currently being developed by the Universidad de Costa Rica's Instituto Clodomiro Picado.[45]

References

- 1 2 Spawls, Stephen (2010). "Dendroaspis polylepis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2010: e.T177584A7461853. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2010-4.RLTS.T177584A7461853.en. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Dendroaspis polylepis". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- 1 2 3 Uetz, Peter; Hallermann, Jakob. "Dendroaspis polylepis Günther, 1864". Reptile Database. Zoological Museum Hamburg. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ↑ Mason, G.H. (1862). Zululand, a mission tour in South Afrika [Africa]. London: J.A.Nisbet. p. 183.

- ↑ Hawes, William (1859). "On the Cape Colony, its products and resources". Journal of the Society of Arts. 7: 244–257 [252].

- ↑ Günther, Albert (1864). "Report on a collection of reptiles and fishes made by Dr. Kirk in the Zambesi and Nyassa Regions". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London: 303–14 [310].

- ↑ Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1980). A Greek-English Lexicon (Abridged ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. pp. 410, 575. ISBN 978-0-19-910207-5.

- ↑ "Definition of mamba in English". Oxford Dictionaries. OED. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- ↑ Loveridge, Arthur (1951). "On reptiles and amphibians for Tanganyika Territory collected by C.J. P. Ionides". Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard College. 106: 175–204 [201].

- ↑ Peters, Wilhem Carl Hartwig (1873). "Über zwei Giftschlangen aus Afrika und über neue oder weniger bekannte Gattungen und Arten von Batrachiern". Monatsberichte der Königlichen Preussische Akademie des Wissenschaften zu Berlin. Jahre 1873 (1874): 411–18.

- ↑ Boulenger, George Albert (1896). Catalogue of the snakes in the British Museum (Natural History). London, United Kingdom: Printed by order of the Trustees British Museum (Natural History). Department of Zoology. p. 437.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Haagner, G.V.; Morgan, D.R. (1993). "The maintenance and propagation of the Black mamba Dendroaspis polylepis at the Manyeleti Reptile Centre, Eastern Transvaal". International Zoo Yearbook. 32 (1): 191–196. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1090.1993.tb03534.x.

- ↑ Figueroa, A.; McKelvy, A. D.; Grismer, L. L.; Bell, C. D.; Lailvaux, S. P. (2016). A species-level phylogeny of extant snakes with description of a new colubrid subfamily and genus. PLoS ONE. 11. pp. e0161070. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0161070. ISBN 9780643106741. PMC 5014348. PMID 27603205.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Spawls, Stephen; Howell, Kim; Drewes, Robert; Ashe, James (2017). A Field Guide to the Reptiles of East Africa (2nd ed.). Bloomsbury. pp. 1201–1202. ISBN 978-1-4729-3561-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Marais, Johan (2004). A complete guide to the snakes of southern Africa (New ed.). Cape Town: Struik. pp. 95–97. ISBN 978-1-86872-932-6.

- 1 2 Mattison, Chris (1987). Snakes of the World. New York: Facts on File, Inc. pp. 84, 120. ISBN 978-0-8160-1082-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 FitzSimons, Vivian F.M. (1970). A Field Guide to the Snakes of Southern Africa (Second ed.). HarperCollins. pp. 167–169. ISBN 978-0-00-212146-0.

- 1 2 3 4 "Black mamba". National Geographic Society. 2010-09-10. Retrieved 2010-03-12.

- 1 2 3 4 Håkansson, Thomas; Madsen, Thomas (1983). "On the Distribution of the Black Mamba (Dendroaspis polylepis) in West Africa". Journal of Herpetology. 17 (2): 186–189. doi:10.2307/1563464. JSTOR 1563464.

- ↑ "Watch a Mongoose Swing From a Deadly Snaked". National Geographic Society. 2017-10-03. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ↑ "Mongoose Vs. Snake - Nat Geo Wild". Nat Geo Wild. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- 1 2 Strydom, Daniel (1971-11-12). "Snake Venom Toxins" (PDF). The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 247 (12): 4029–42. PMID 5033401. Retrieved 2010-04-24.

- ↑ The new encyclopedia of Reptiles (Serpent). Time Book Ltd. 2002.

- 1 2 JERRY G. WALLS, "The World's Deadliest Snakes", Reptiles

- ↑ O'Shea, M. (2005). Venomous Snakes of the World. United Kingdom: New Holland Publishers. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-691-12436-0.

... in common with other snakes they prefer to avoid contact; ... from 1957 to 1963 ... including all seven black mamba bites - a 100 per cent fatality rate

- ↑ Laustsen, Andreas Hougaard; Lomonte, Bruno; Lohse, Brian; Fernandez, Julian; Maria Gutierrez, Jose (2015). "Unveiling the nature of black mamba (Dendroaspis polylepis) venom through venomics and antivenom immunoprofiling: Identification of key toxin targets for antivenom development". Journal of Proteomics. 119: 126–142. doi:10.1016/j.jprot.2015.02.002. PMID 25688917.

- 1 2 3 4 Branch, Bill (1988). Field Guide to the Snakes and Other Reptiles of Southern Africa. London: New Holland. p. 95. ISBN 978-1-85368-112-7.

- 1 2 Müller, G.J.; Modler, H.; Wium, C.A.; Veale, D.J.H.; Marks, C. J. (October 2012). "Snake bite in southern Africa: diagnosis and management". CME. 30 (10): 362–381. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- 1 2 Spawls, S.; Branch, B. (1995). The dangerous snakes of Africa: natural history, species directory, venoms, and snakebite. Dubai: Oriental Press: Ralph Curtis-Books. pp. 49–51. ISBN 978-0-88359-029-4.

- 1 2 3 Fry, Bryan, Deputy Director, Australian Venom Research Unit, University of Melbourne (March 9, 2002). "Snakes Venom LD50 – list of the available data and sorted by route of injection ". venomdoc.com. (archived) Retrieved October 14, 2013.

- 1 2 Sherman A. Minton, (May 1, 1974) Venom diseases, Page 116

- ↑ Philip Wexler, 2005, Encyclopedia of toxicology, Page 59

- ↑ Thomas J. Haley, William O. Berndt, 2002, Toxicology, Page 446

- ↑ Scott A Weinstein, David A. Warrell, Julian White and Daniel E Keyler (Jul 1, 2011) " Bites from Non-Venomous Snakes: A Critical Analysis of Risk and Management of "Colubrid" Snake Bites (page 246)

- ↑ Visser, J; Chapman, DS (1978). Snakes and Snakebite: Venomous snakes and management of snake bite in Southern Africa. Purnell. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-86843-011-9.

- 1 2 3 4 S.B. Dreyer; J.S. Dreyer (November 2013). "Snake Bite: A review of Current Literature". East and Central African Journal of Surgery. 18 (3): 45–52. ISSN 2073-9990. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ↑ Závada J.; Valenta J.; Kopecký O.; Stach Z.; Leden P. "Black Mamba Dendroaspis Polylepis Bite: A Case Report". Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care, First Faculty of Medicine, Charles University in Prague and General University Hospital in Prague, Prague, Czech Republic. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ↑ Diochot, Sylvie; Baron, Anne; Salinas, Miguel; Douguet, Dominique; Scarzello, Sabine; Dabert-Gay, Anne-Sophie; Debayle, Delphine; Friend, Valérie; Alloui, Abdelkrim (2012-10-25). "Black mamba venom peptides target acid-sensing ion channels to abolish pain". Nature. 490 (7421): 552–555. doi:10.1038/nature11494. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 23034652.

- ↑ "Scientists gather in Kruger National Park for Savanna Science Network Meeting". South African Tourism. 5 March 2013. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ↑ "Surviving a Black Mamba bite". Siyabona Africa - Kruger National Park. Siyabona Africa. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ↑ "British trainee safari guide killed by bite from a black mamba snake he thought had just brushed his hand". UK Daily Mail. 2011-12-13. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ↑ "Black mamba snake bite killed British student Nathan Layton". Mirror News. 2011-12-13. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ↑ Gutiérrez, José María; Calvete, Juan J.; Habib, Abdulrazaq G.; Harrison, Robert A.; Williams, David J.; Warrell, David A. (2017). "Snakebite envenoming". Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 3 (3): 17063. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2017.63. PMID 28905944.

- ↑ Davidson, Terence. "IMMEDIATE FIRST AID". University of California, San Diego. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

- ↑ Sánchez, Andrés; et al. (2017). "Expanding the neutralization scope of the EchiTAb-plus-ICP antivenom to include venoms of elapids from Southern Africa". Toxicon. 125: 59–64. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2016.11.259. PMID 27890775. Retrieved 2016-11-24.

Further reading

- Thorpe, Roger S.; Wolfgang Wüster, Anita Malhotra (1996). Venomous Snakes: Ecology, Evolution, and Snakebite. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-854986-4

- McDiarmid, Roy W.; Jonathan A. Campbell; T'Shaka A. Tourè (1999). Snake Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, Volume 1. Washington, District of Columbia: Herpetologists' League. ISBN 978-1-893777-01-9

- Dobiey, Maik; Vogel, Gernot (2007). Terralog: Venomous Snakes of Africa (Terralog Vol. 15). Aqualog Verlag GmbH.; 1st edition. ISBN 978-3-939759-04-1

- Mackessy, Stephen P. (2009). Handbook of Venoms and Toxins of Reptiles. CRC Press; 1st edition. ISBN 978-0-8493-9165-1

- Greene, Harry W.; Fogden, Michael; Fogden, Patricia (2000). Snakes: The Evolution of Mystery in Nature. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-22487-2

- Spawls, Stephen; Ashe, James; Howell, Kim; Drewes, Robert C. (2001). Field Guide to the Reptiles of East Africa: All the Reptiles of Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-12-656470-9

- Broadley, D.G.; Doria, C.T.; Wigge, J. (2003). Snakes of Zambia: An Atlas and Field Guide. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Edition Chimaira. ISBN 978-3-930612-42-0

- Engelmann, Wolf-Eberhard (1981). Snakes: Biology, Behavior, and Relationship to Man. Leipzig; English version NY, US: Leipzig Publishing; English version published by Exeter Books (1982). ISBN 0-89673-110-3

- Minton, Sherman A. (1969). Venomous Reptiles. US: New York Simon Schuster Trade. ISBN 978-0-684-71845-3

- FitzSimons, Vivian FM (1970). A field guide to the snakes of Southern Africa. Canada: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-212146-8

- Department of the Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery (2013). Venomous Snakes of the World: A Manual for Use by U.S. Amphibious Forces. Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 978-1-62087-623-7

- Branch, Bill (2005). Photographic Guide to Snakes Other Reptiles and Amphibians of East Africa. Sanibel Island, Florida: Ralph Curtis Books. ISBN 978-0-88359-059-1

- Mara, Wil; Collins, Joseph T; Minton, SA (1993). Venomous Snakes of the World. TFH Publications Inc. ISBN 978-0-86622-522-9

- Stocker, Kurt F. (1990). Medical Use of Snake Venom Proteins. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-5846-3

- Mebs, Dietrich (2002). Venomous and Poisonous Animals: A Handbook for Biologists, Toxicologists and Toxinologists, Physicians and Pharmacists. Medpharm. ISBN 978-0-8493-1264-9

- White, Julian; Meier, Jurg (1995). Handbook of Clinical Toxicology of Animal Venoms and Poisons. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-4489-3

- Vitt, Laurie J; Caldwell, Janalee P. (2013). Herpetology, Fourth Edition: An Introductory Biology of Amphibians and Reptiles. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-386919-7

- Tu, Anthony T. (1991). Handbook of Natural Toxins, Vol. 5: Reptile Venoms and Toxins. Marcel Dekker. ISBN 978-0-8247-8376-1

- Mattison, Chris (1995). The Encyclopedia of Snakes. Facts on File; 1st U.S. edition. ISBN 978-0-8160-3072-9

- Coborn, John (1991). The Atlas of Snakes of the World. TFH Publications. ISBN 978-0-86622-749-0

External links

![]()

| Wikispecies has information related to Dendroaspis polylepis |