Berthe Morisot

| Berthe Morisot Madame Eugène Manet | |

|---|---|

Berthe Morisot | |

| Born |

Berthe Marie Pauline Morisot January 14, 1841 Bourges, Cher, France |

| Died |

March 2, 1895 (aged 54) Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Known for | Painting |

| Notable work | The Cradle, View of Paris from the Trocadero, After Lunch, Summer's Day |

| Movement | Impressionism |

| Spouse(s) | Eugène Manet |

Berthe Marie Pauline Morisot (French: [mɔʁizo]; January 14, 1841 – March 2, 1895) was a painter and a member of the circle of painters in Paris who became known as the Impressionists. She was described by Gustave Geffroy in 1894 as one of "les trois grandes dames" of Impressionism alongside Marie Bracquemond and Mary Cassatt.[1]

In 1864, she exhibited for the first time in the highly esteemed Salon de Paris. Sponsored by the government, and judged by Academicians, the Salon was the official, annual exhibition of the Académie des beaux-arts in Paris. Her work was selected for exhibition in six subsequent Salons[2] until, in 1874, she joined the "rejected" Impressionists in the first of their own exhibitions, which included Paul Cézanne, Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Alfred Sisley. It was held at the studio of the photographer Nadar.

She was married to Eugène Manet, the brother of her friend and colleague Édouard Manet.

Early life and education

Morisot was born in Bourges, France, into an affluent bourgeois family. Her father, Edmé Tiburce Morisot, was the prefect (senior administrator) of the department of Cher. He also studied architecture at École des Beaux Arts.[3] Her mother, Marie-Joséphine-Cornélie Thomas, was the great-niece of Jean-Honoré Fragonard, one of the most prolific Rococo painters of the ancien régime.[4] She had two older sisters, Yves (1838–1893) and Edma (1839–1921), plus a younger brother, Tiburce, born in 1848. The family moved to Paris in 1852, when Morisot was a child.

It was commonplace for daughters of bourgeois families to receive art education, so Berthe and her sisters Yves and Edma were taught privately by Geoffroy-Alphonse Chocarne and Joseph Guichard. Morisot and her sisters initially started taking lessons so that they could each make a drawing for their father for his birthday.[3] In 1857 Guichard, who ran a school for girls in Rue des Moulins, introduced Berthe and Edma to the Louvre gallery where they could learn by looking, and from 1858 they learned by copying paintings. The Morisots were not only forbidden to work at the museum unchaperoned, but they were also totally barred from formal training.[5] However, the museum served another key purpose, because it enabled them to get acquainted with young male artists, such as Manet and Monet. [6]

He also introduced them to the works of Gavarni.[7] Guichard later became the director of École des Beaux Arts where Morisot's father earned his degree.[3] In 1861 Guichard introduced Berthe to Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, a French painter, who influenced her early landscapes.[8][9]

As art students, Berthe and Edma worked closely together until 1869, when Edma married Adolphe Pontillon, a naval officer, moved to Cherbourg, and had less time to paint. Letters between the sisters show a loving relationship, underscored by Berthe's regret at the distance between them and Edma's withdrawal from painting. Edma wholeheartedly supported Berthe's continued work and their families always remained close. Edma wrote “… I am often with you in thought, dear Berthe. I’m in your studio and I like to slip away, if only for a quarter of an hour, to breathe that atmosphere that we shared for many years…”.[10][11][12]

Her sister Yves married Theodore Gobillard, a tax inspector, in 1866, and was painted by Edgar Degas as Mrs Theodore Gobillard (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York).[10][11][13]

Morisot registered as a copyist at the Louvre where she befriended other artists and teachers including Camille Corot, the pivotal landscape painter of the Barbizon School who also excelled in figure painting. In 1860, under Corot's influence she took up the plein air (outdoors) method of working. By 1863 she was studying under Achille Oudinot, another Barbizon painter. In the winter of 1863–64 she studied sculpture under Aimé Millet, but none of her sculpture is known to survive.[7]

Main periods of Morisot's work

Training, 1857-1870

It is hard to trace the stages of Morisot's training and to tell the exact influence of her teachers because she was never pleased with her work and she destroyed nearly all of the artworks she produced before 1869. Her first teacher, Geoffroy-Alphonse Chocarne, taught her the basics of drawing. After several months, Morisot began to take classes taught by Joseph Guichard. During this period, she found her talents in drawing and drew mostly ancient classical figures. When Morisot expressed her interests in plein-air painting, Guichard sent her to follow Camille Corot and Achille Oudinot. Painting outdoor, she played with the light and time with the use of watercolors which are easy to carry. At that time, Morisot also became interested in pastel. [14]

Watercolorist, 1870-1874

During this period, she practiced watercolors for most of the time. Her choice of colors is rather restrained; however, the delicate repetition of hues renders a balanced effect. Due to specific characteristics of watercolors as a medium, Morisot was able to create a translucent atmosphere and feathery touch, which contribute to the freshness in her paintings. In fact, between 1870-1873, Morisot still found oil painting difficult and she could only apply her watercolor works to the oil paintings. [15]

Impressionism, 1875–1885

During this time, Morisot felt more confident about oil painting, and she would paint in oil, watercolor and pastel at the same time, as Degas did. Morisot painted very quickly but she also prepared a lot in advance. Firstly, she made countless studies of her subject matter. Her subjects were repeatedly drawn from her life so she became quite familiar with them. Morisot did much sketching as preparation, so she could paint "a mouth, eyes, and a nose with a single brushstroke." Secondly, when it became inconvenient to paint outdoors, the very highly finished watercolors done in the preparatory stages allowed her to continue painting indoors later.[16]

Turning, 1885-1887

Since 1885, drawing began to dominate in Morisot's works. Morisot actively experimented with charcoals and color pencils. What seems paradoxical is that her reviving interest in drawing was motivated by her Impressionist friends, who are known for blurring forms. Morisot put her emphasis on the clarification of the form and lines during this period. In addition, she was under the influence of developing technology of photography and Japonisme, shown in her composition without a clear center. [17]

New Painting Way, 1887-1895

Morisot started to use the technique of squaring and the medium of tracing paper to transcribe her drawing to the canvas exactly. By employing this new method, Morisot was able to create brand-new types of compositions where more complicated interaction between figures in the paintings and the numerous adjustments emerged. She stressed the composition and the forms while her impressionist brushstrokes still remained. Her original synthesis of the impressionist touch with broad strokes and light reflections and the graphic approach featured by clear lines made her late works really distinctive.[18]

Style and Technique

Morisot's paintings are commented as full of "feminine charm", which features elegance and lightness. Her brushstrokes are as light as the touch of a petal; therefore, French critics often use the verb "effleurer" (to touch lightly, brush against) to describe her technique. In her early life, Morisot painted in open air as other Impressionists to look for truths in observation.[19] Around 1880 she began painting on unprimed canvases—a technique Manet and Eva Gonzalès also experimented with at the time[20]—and her brushwork became looser. In 1888–89, her brushstrokes transitioned from short, rapid strokes to long, sinuous ones that define form.[21] The outer edges of her paintings were often left unfinished, allowing the canvas to show through and increasing the sense of spontaneity. After 1885, she worked mostly from preliminary drawings before beginning her oil paintings.[22] She also worked in oil paint, watercolors, and pastel simultaneously, and sketched using various drawing media. Morisot’s works are almost always small in scale.

Morisot creates a sense of space and depth through the use of color. Although her color palette was somehow limited, her fellow impressionists regarded her as a "virtuoso colorist".[22] She typically made expansive use of white to create a sense of transparency, whether used as a pure white or mixed with other colors. In her large painting, The Cherry Tree, colors are more vivid but are still used to emphasize form.[22]

Furthermore, it is no wonder that the style and techniques that Morisot applied were greatly inspired by her Impressionist friends. Inspired by Manet's drawings, she kept the use of colors to the minimum when constructing a motif. Responding to the experiments conducted by Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas, Morisot used barely tinted whites to harmonize the paintings. Like Degas, she played with three media simultaneously in one painting: watercolor, pastel, and oil paints. In the second half of her career, she learned from Renoir by mimicking his motifs.[23] She also shared an interest in keeping a balance between the density of figures and the atmospheric traits of light with Renoir in her later works.[24]

Subjects

Morisot painted what she experienced on a daily basis. Most of her paintings include domestic scenes about family, children, ladies, and flowers, depicting what women's life was like in the late nineteenth century. Instead of portraying the public space and the society, Morisot preferred private, intimate scenes.[25] It somehow reflects the cultural restrictions of her class and gender at that time. Like her fellow Impressionist Mary Cassatt, she focused on domestic life and portraits in which she could use family and personal friends as models, including her daughter Julie and sister Edma. The stenographic presentation of her daily life conveys a strong hope to stop the fleeting passage of time.[26] By portraying flowers, she used metaphors to celebrate womanhood.[27] Prior to the 1860s, Morisot painted subjects in line with the Barbizon school before turning to scenes of contemporary femininity.[28] Paintings like The Cradle (1872), in which she depicted current trends for nursery furniture, reflect her sensitivity to fashion and advertising, both of which would have been apparent to her female audience. Her works also include landscapes, garden settings, boating scenes, and theme of boredom or ennui. [29] Later in her career Morisot worked with more ambitious themes, such as nudes.[30] In her late works, she often referred to the past to recall the memory of her earlier life and youth, and her departed companions.[31]

Impressionism

Morisot's first appearance in the Salon de Paris came at the age of twenty-three in 1864, with the acceptance of two landscape paintings. She continued to show regularly in the Salon, to generally favorable reviews, until 1873, the year before the first Impressionist exhibition. She exhibited with the Impressionists from 1874 onwards, only missing the exhibition in 1878 when her daughter was born.[32]

Impressionism’s alleged attachment to brilliant color, sensual surface effects, and fleeting sensory perceptions led a number of critics to assert in retrospect that this style, once primarily the battlefield of insouciant, combative males, was inherently feminine and best suited to women's weaker temperaments, lesser intellectual capabilities, and greater sensibility.[33]

During her 1874 exhibition with the Impressionists, such as Monet and Manet. Le Figaro critic Albert Wolff noted that the Impressionists consisted of "five or six lunatics of which one is a woman...[whose] feminine grace is maintained amid the outpourings of a delirious mind." [34]

Morisot's mature career began in 1872. She found an audience for her work with Durand-Ruel, the private dealer, who bought twenty-two paintings. In 1877, she was described by the critic for Le Temps as the "one real Impressionist in this group."[35] She chose to exhibit under her full maiden name instead of using a pseudonym or her married name.[36] As her skill and style improved, many began to rethink their opinion toward Morisot. In the 1880 exhibition, many reviews judged Morisot among the best, even including Le Figaro critic Albert Wolff.[37]

Personal life

Morisot came from an eminent family, the daughter of a government official and the granddaughter of a famous Rococo artist Jean-Honoré Fragonard[38]. She met her longtime friend and colleague, Édouard Manet, in 1868. By the introduction of Manet, Morisot was married to Édouard's brother, Eugène Manet in 1874. In 1878 she gave birth to her only child, Julie, who posed frequently for her mother and other Impressionist artists, including Renoir and her uncle Édouard. Morisot had a close relationship with Édouard Manet who exert a tremendous influence on her. Correspondence between them shows warm affection, and Manet gave her an easel as a Christmas present. Morisot often posed for Manet and there are several portrait painting of Morisot such as Repose (Portrait of Berthe Morisot) and Berthe Morisot with a Bouquet. [39] Morisot died on March 2, 1895, in Paris, of pneumonia contracted while attending to her daughter Julie's similar illness, and thus orphaning her at the age of 16. She was interred in the Cimetière de Passy.

Works

Selection of Works

- This list is incomplete, you can help by expanding it with certified entries.

This limited selection is based in part on the book Berthe Morisot by Charles F. Stuckey, William P. Scott and Susan G. Lindsay, which is in turn drawn from the 1961 catalogue by Marie-Louise Bataille, Rouaart Denis and Georges Wildenstein. There are variations between the dates of execution, first showing and purchase. Titles may vary between sources.

Early years of Impressionism, 1864-1874

- Étude, 1864, oil on canvas, 60.3 × 73 cm, private collection[40]

- Chaumière en Normandie, 1865, oil on canvas, 46 × 55 cm, private collection[41]

- La Seine en aval du pont d'Iéna, 1866, oil on canvas, 51 × 73 cm, private collection[42]

- La Rivière de Pont Aven à Roz-Bras, 1867, oil on canvas, 55 × 73 cm, private collection - Chicago[43]

- Bateaux à l'aurore, 1869, pastel on paper, 19.7 × 26.7 cm, private collection[44]

- Jeune fille à sa fenêtre, 1869, oil on canvas, 36.8 × 45.4 cm, private collection

- Madame Morisot et sa fille Madame Pontillon (La Lecture), 1869-1870, oil on canvas, 101 × 81.8 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.[45]

- Le Port de Cherbourg, 1871, crayon and watercolour on paper, 15.6 × 20.3 cm, private collection of Paul Mellon, Upperville, Virginia[46]

- Le Port de Cherbourg, 1871, oil on canvas, 41.9 × 55.9 cm, private collection of Paul Mellon, Upperville, Virginia[47]

- Vue de paris de hauteurs du Trocadéro, 1871, oil on canvas, 46.1 × 81.5 cm, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, California[48]

- Femme et enfant au balcon, 1871-72, watercolor, 20.6 × 17.3 cm, Art Institute of Chicago[49][50][51]

- Intérieur, 1871, oil on canvas, 60 × 73 cm, private collection[52]

- Portrait de Madame Pontillon, 1871, pastel on paper, 85.5 × 65.8 cm, Louvre - drawings cabinet[53] gift of Madame Edma Pontillon to the Louvre in 1921, in the collection of the Musée d'Orsay[54]

- L'Entrée du port, 1871,[Note 1] watercolour on paper, 24.9 × 15.1 cm, Musée Léon-Alègre, Bagnols-sur-Cèze - drawings cabinet[55]

- Madame Pontillon et sa fille Jeanne sur un canapé, 1871, watercolour on paper, 25.1 × 25.9 cm, National Gallery of Art,[56]

- Jeune fille sur un banc (Edma Pontillon), 1872, oil on canvas, 33 × 41 cm,[57]

- Cache-cache, 1872, oil on canvas, 33 × 41 cm, Private collection[58]

- Le Berceau, 1872, oil on canvas, 56 × 46 cm Musée d'Orsay, Paris

- La Lecture (Edma lisant), also titled L'Ombrelle verte, 1873, oil on canvas, 45.1 × 72.4 cm, Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio[58]

- Sur la plage des Petites-Dalles, 1873, oil on canvas, 24.1 × 50.2 cm, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Virginia[59]

- Madame Boursier et sa fille, 1873, oil on canvas, 74 × 52 cm, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts[60]

- Le Village de Maurecourt, 1873, pastel on paper, 47 × 71.8 cm, private collection[61]

- Coin de Paris vu de Passy, 1873, pastel on paper, 27 × 34.9 cm, private collection[62]

- Sur la terrasse, 1874, oil on canvas, 45 × 54 cm, Musée du Petit Palais, Paris[63]

- Portrait de Madame Hubbard, 1874, oil on canvas, 50.5 × 81 cm, Ordrupgaard museum de Copenhagen[64]

- Femme et enfant au bord de la mer , 1874, watercolor on paper, 16 × 21.3 cm, private collection[65]

Expertise and innovation 1875-1883

- Percher de blanchisseuses , 1875, Oil on canvas 33 × 40.8 cm, National Gallery of Art,[62]

- Jeune fille au miroir, 1875, oil on canvas, 54 × 45 cm, private collection[66]

- Scène de port dans l'île de Wight, 1875, oil on canvas, 48 × 36 cm private collection[67]

- Scène de port dans l'île de Wight, 1875, oil on canvas, 43 × 64 cm, Newark Museum, Newark, New Jersey[68]

- Eugène Manet à l'île de Wight, 1875, oil on canvas, 38 × 46 cm private collection[69]

- Avant d'un yacht, 1875, watercolour on paper, 20.6 × 26.7 cm, Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts[70]

- Femme à sa toilette, 1875, oil on canvas, 46 × 38 cm private collection[71]

- Femme à sa toilette , 1875-1880, hst, dim; 60.3 × 80.4 cm, Coll. Art Institute of Chicago

- Portrait de femme (Avant le théâtre), 1875, oil on canvas, 57 × 31 cm, Galerie Schröder & Leisewitz, Bremen[70]

- Jeune femme au bal encore intitulé Jeune femme en toilette de bal, 1876, oil on canvas, 86 × 53 cm Musée d'Orsay[72]

- Au Bal ou Jeune fille au bal, 1875, oil on canvas, 62 × 52 cm, Musée Marmottan-Monet, Paris

- Le Corsage noir , 1876, oil on canvas, 73 × 59.8 cm National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin[73]

- Le Psyché, 1876, oil on canvas, 65 × 54 cm, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid[74]

- Rêveuse, 1877, pastel on canvas, 50.2 × 61 cm, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri[75]

- L'Été, encore intitulé Jeune femme près d'une fenêtre 1878, oil on canvas, 76 × 61 cm, Musée Fabre, Montpellier[76]

- Jeune feme assise, 1878-1879, huile sur toile 80 × 100 cm, private collection New York[77]

- Jeune fille de dos à sa toilette, encore intitulé Femme à sa toilette 1879, oil on canvas, 60.3 × 80.4 cm Art Institute of Chicago[78]

- Le Lac du Bois de Boulogne (Jour d'été), 1879, 45.7 × 75.3 cm, National Gallery, London[79]

- Dans le jardin (Dames cueillant des fleurs), 1879, oil on canvas, 61 × 73.5 cm, Nationalmuseum Stockholm[80]

- Jeune femme en toilette de bal (Young Woman in Evening Dress), 1879, oil on canvas, 71 x 54 cm, Musée d’Orsay, Paris[81]

- Hiver, 1880, oil on canvas, 73.5 × 58.5 cm, Dallas Museum of Art[82]

- Deux filles assises près d'une table, 1880, crayon and watercolour on paper 19,6 × 26.6 cm private collection Germany

- Plage à Nice 1881-1882, watercolour on paper 42 × 55 cm, Nationalmuseum Stockholm[83]

- Le Port de Nice, 1881-1882, oil on canvas, 53 × 43 cm private collection[84]

- Le Port de Nice, 1881-1882, oil on canvas, 41 × 55 cm private collection[85]

- Le Port de Nice 1881 (?)third version format 38 × 46 cm conserved at Dallas Museum of Art

- Le Thé, 1882, oil on canvas, 57.5 × 71.5 cm, Fondation Madelon Vaduz, Liechtenstein[86]

- Le Port de Nice, 1881-1882, oil on canvas, 53 × 43 cm private collection[84]

- La Fable, 1883, oil on canvas, 65 × 81 cm private collection[87] · [88]

- Le Jardin (Femmes dans le jardin) (1882-1883) oil on canvas, 99.1 × 127 cm, Sara Lee Corporation, Chicago[89]

- Eugène Manet et sa fille au jardin 1883, oil on canvas, 60 × 73, private collection [90]

- Dans le jardin à Maurecourt, 1883, oil on canvas, 54 × 65 cm, Toledo Museum of Art[91]

- Le Quai de Bougival, 1883, oil on canvas, 55.5 × 46 cm, Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo[92]

- Julie et son bateau (Enfant jouant), 1883, watercolour on paper, 25 × 16 cm, private collection [93]

- La Meule de foin 1883, oil on canvas, 55.3 × 45.7 cm, private collection, New York[94] · [95]

Fully developed 1884-1894

- Dans la véranda, 1884, oil on canvas, 81 × 10 cm, private collection.[96]

- Julie avec sa poupée, 1884, oil on canvas, 82 × 10 cm, private collection.[97]

- Petite fille avec sa poupée (Julie Manet), 1884, pastel on paper, 60 × 46 cm, private collection.[98]

- Sur le lac, 1884, oil on canvas, 65 × 54 cm, private collection.[99]

- The Artist's Daughter, Julie, with her Nanny, c. 1884, oil on canvas, Minneapolis Institute of Art[100][101]

- Autoportrait, 1885, pastel on paper, 47.5 × 37.5 cm, Art Institute of Chicago.[102]

- Autoportrait avec Julie, 1885, oil on canvas, 72 × 91 cm, private collection.[103]

- Jeune femme assise au Bois de Boulogne, 1885, watercolour on paper, 19 × 28 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.[104]

- La Forêt de Compiègne, 1885, oil on canvas, 54.2 × 64.8 cm, Art Institute of Chicago.[105]

- Le Bain (Jeune file se coiffant), 1885-1886, oil on canvas, 81.1 × 72.3 cm, Art Institute of Chicago.[106]

- Dans la salle à manger, 1885-1886, oil on canvas, 61.3 × 50 cm, National Gallery of Art.[107]

- Le Lever, 1886, oil on canvas, 65 × 54 cm, collection Durand-Ruel.[108]

- Intérieur à Jersey (Intérieur de cottage), 1886, oil on canvas, 50 × 60 cm, Musée communal des beaux-arts d'Ixelles.[109]

- Femme s'essuyant, 1886-1887, pastel on paper, 42 × 41 cm, Non localisé.[110]

- Julie avec un chat, 1887, drypoint, 14.5 × 11.3 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington.[111]

- Nu de dos, 1887, charcoal on paper, 57 × 43 cm, private collection.[112]

- Éventail en médaillon, 1887, watercolour on silk fan, private collection.[113]

- Portrait de Paule Gobillard, 1887, coloured pencil on paper, 27.9 × 22.9 cm, Reader's Digest Association, New York.[114]

- Le Lac du Bois de Boulogne, 1887, watercolour on paper, 29.5 × 22.2 cm, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington.[115]

- Fillette lisant (La lecture), 1888, oil on canvas, 74.3 × 92.7 cm, Museum of Fine Arts (St. Petersburg, Florida).[116]

- Berthe Morisot and Julie Manet, c.1888-1890, drypoint, 18.42 x 13.49 cm, Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis.[117]

- La Cueillette des oranges, 1889, pastel, 61 × 46 cm, Musée d'art et d'histoire de Provence, Grasse.[118]

- Sous l'oranger (Julie), 1889, oil on canvas, 54 × 65 cm, private collection.[119]

- L'Île du Bois de Boulogne, 1889, oil on canvas, 68.4 × 54.6 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington.[120]

- Le Flageolet (Julie Manet et Jeanne Gobillard), 1891, oil on canvas, 56 × 87 cm, private collection.[121]

- Le Cerisier 1891, 1891, oil on canvas, 138 × 88.9 cm, private collection, Washington.[122]

- Étude pour Le Cerisier, 1891, pastel on paper, 45.7 × 48.9 cm, The Reader's Digest Association.[123]

- Julie Manet avec son lévrier, 1893, oil on canvas, 73× 80 cm, Musée Marmottan-Monet, Paris.[124]

- Les Enfants de Gabriel Thomas, 1894, oil on canvas, 100 × 80 cm, Musée d'Orsay, Paris.[125]

- La Coiffure, 1894, oil on canvas, 100 × 80 cm, Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes (Buenos Aires).[126]

- Jeune fille aux cheveux noirs, 1894, pencil and watercolour, 23.1 × 16.8 cm, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia.[127]

Gallery

The Artist's Sister at a Window, 1869, National Gallery of Art

The Artist's Sister at a Window, 1869, National Gallery of Art The Harbor at Lorient, 1869, National Gallery of Art

The Harbor at Lorient, 1869, National Gallery of Art On the Balcony, 1872, New York

On the Balcony, 1872, New York Reading, 1873, Cleveland Museum of Art

Reading, 1873, Cleveland Museum of Art Le Berceau (The Cradle), 1872, Musée d'Orsay

Le Berceau (The Cradle), 1872, Musée d'Orsay_-_Berthe_Morisot.jpg) Portrait of Mme Boursier and Her Daughter, c. 1873, Brooklyn Museum

Portrait of Mme Boursier and Her Daughter, c. 1873, Brooklyn Museum Hanging the Laundry out to Dry, 1875, National Gallery of Art

Hanging the Laundry out to Dry, 1875, National Gallery of Art Lady at her Toilette, 1875 The Art Institute of Chicago

Lady at her Toilette, 1875 The Art Institute of Chicago Eugène Manet on the Isle of Wight, 1875, Musée Marmottan Monet

Eugène Manet on the Isle of Wight, 1875, Musée Marmottan Monet The Dining Room, c. 1875 National Gallery of Art

The Dining Room, c. 1875 National Gallery of Art

Winter aka Woman with a Muff, 1880, Dallas Museum of Arts

Winter aka Woman with a Muff, 1880, Dallas Museum of Arts Child among the Hollyhocks, 1881, Wallraf-Richartz Museum

Child among the Hollyhocks, 1881, Wallraf-Richartz Museum The Artists' Daughter Julie With Her Nanny, c.1884, Minneapolis Institute of Art

The Artists' Daughter Julie With Her Nanny, c.1884, Minneapolis Institute of Art The Bath (Girl Arranging Her Hair), 1885–86, Clark Art Institute

The Bath (Girl Arranging Her Hair), 1885–86, Clark Art Institute Julie Manet et son Lévrier Laerte, 1893, Musée Marmottan Monet

Julie Manet et son Lévrier Laerte, 1893, Musée Marmottan Monet

Portraits of Berthe Morisot

Detail from The Balcony by Édouard Manet, with the portrait of Berthe in the foreground. 1868.

Detail from The Balcony by Édouard Manet, with the portrait of Berthe in the foreground. 1868. Berthe Morisot posing for The Rest. 1870. By Édouard Manet.

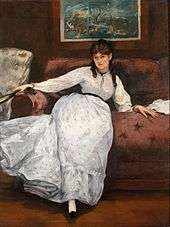

Berthe Morisot posing for The Rest. 1870. By Édouard Manet. Berthe Morisot on a divan couch, 1872, by Édouard Manet.

Berthe Morisot on a divan couch, 1872, by Édouard Manet. Portrait of Berthe Morisot with a Fan, 1874 by Édouard Manet.

Portrait of Berthe Morisot with a Fan, 1874 by Édouard Manet. Portrait of Berthe Morisot, 1876, by Marcellin Desboutin.

Portrait of Berthe Morisot, 1876, by Marcellin Desboutin. Portrait of Berthe Morisot. 1882. By Édouard Manet.

Portrait of Berthe Morisot. 1882. By Édouard Manet. Berthe Morisot au soulier rose. 1872. By Édouard Manet. Hiroshima Museum of Art.

Berthe Morisot au soulier rose. 1872. By Édouard Manet. Hiroshima Museum of Art. Berthe Morisot and her daughter Julie Manet, 1894, by Pierre-Auguste Renoir.

Berthe Morisot and her daughter Julie Manet, 1894, by Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Berthe Morisot, 1892, by Renoir.

Berthe Morisot, 1892, by Renoir.

Exhibitions

- 1864 exhibited two paintings in the Paris Salon, additional years 1865-6, 1868, 1870, 1872-3

- 1874 first Impressionist exhibition, showed twelve works

- 1875 Auction at Hotel Drouot, showed twelve works

- 1880 Paris exhibition, reviews judged her among the best.

- 1883 London exhibition, organized by Paul Durand-Ruel including three works by Morisot

- 1892 first solo-exhibition of forty-three works in Paris by Galerie Boussod et Valadon

Art market

Morisot's work sold comparatively well. She achieved the two highest prices at a Hôtel Drouot auction in 1875, the Interior (Young Woman with Mirror) sold for 480 francs, and her pastel On the Lawn sold for 320 francs.[128][129] Her works averaged 250 francs, the best relative prices at the auction.[130]

In February 2013, Morisot became the highest priced female artist, when After Lunch (1881), a portrait of a young redhead in a straw hat and purple dress, sold for $10.9 million at a Christie's auction. The painting achieved roughly three times its upper estimate,[131][132][132][133] exceeding the $10.7 million for a sculpture by Louise Bourgeois in 2012.[131]

Legacy

She was portrayed by actress Marine Delterme in a 2012 French biographical TV film directed by Caroline Champetier. The character of Beatrice de Clerval in Elizabeth Kostova's The Swan Thieves is largerly based on Morisot.[134]

She was featured as the "A First Impressionist" in an article written by Anne Truitt in the New York Times on June 3, 1990. [135]

From Melissa Burdick Harmon, a editor at Biography magazine, “While some of Morisot's work may seem to us today like sweet depictions of babies in cradles, at the time these images were considered extremely intimate, as objects related to infants belonged exclusively to the world of women.”[136]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The scene L'Entrée du port is often confused with L'Entrée du port de Cherbourg purchased in 1874 by Durand-Ruel, or confused with Le Port de Cherbourg

References

- ↑ Geffroy, Gustave (1894), "Histoire de l'Impressionnisme", Le Vie artistique: 268 .

- ↑ Denvir, 2000, pp. 29-79.

- 1 2 3 Adler, Kathleen (1987). Berthe Morisot. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. p. 9. ISBN 0801420539.

- ↑ Higonnet, p. 5

- ↑ Harmon, Melissa Burdick. "Monet, Renoir, Degas...Morisot the Forgotten Genius of Impressionism." Biography, vol. 5, no. 6, June 2001, p. 98. EBSCOhost,

- ↑ Harmon, Melissa Burdick. "Monet, Renoir, Degas...Morisot the Forgotten Genius of Impressionism." Biography, vol. 5, no. 6, June 2001, p. 98. EBSCOhost,

- 1 2 Higonnet, Anne (1990). Berthe Morisot. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers. pp. 11–25. ISBN 0-06-016232-5.

- ↑ "Emory Libraries Resources Terms of Use - Emory University Libraries". www.oxfordartonline.com. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000059646.

- ↑ "Emory Libraries Resources Terms of Use - Emory University Libraries". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. doi:10.1093/benz/9780199773787.001.0001/acref-9780199773787-e-00126011.

- 1 2 Yves peinte par Degas

- 1 2 (Stuckey et al, p. 16)

- ↑ Women in the Act of Painting, 9 November 2012, Edma and Berthe by Nancy Bea Miller

- ↑ Berthe Morisot by Anne Higonnet, Berthe Morisot, at Google Books. Page 32

- ↑ Berthe Morisot : 1841-1895. Mathieu, Marianne., Musée Marmottan. Paris. ISBN 9780300182019. OCLC 830199379.

- ↑ Berthe Morisot : 1841-1895. Mathieu, Marianne., Musée Marmottan. Paris. ISBN 9780300182019. OCLC 830199379.

- ↑ Berthe Morisot : 1841-1895. Mathieu, Marianne., Musée Marmottan. Paris. ISBN 9780300182019. OCLC 830199379.

- ↑ Berthe Morisot : 1841-1895. Mathieu, Marianne., Musée Marmottan. Paris. ISBN 9780300182019. OCLC 830199379.

- ↑ Berthe Morisot : 1841-1895. Mathieu, Marianne., Musée Marmottan. Paris. ISBN 9780300182019. OCLC 830199379.

- ↑ Dominique., Rey, Jean (2010). Berthe Morisot. Patry, Sylvie., Morisot, Berthe, 1841-1895., Lalaurie, Louise Rogers. Paris: Flammarion. ISBN 9782080301680. OCLC 646401344.

- ↑ National Museum of Women in the Arts: "The Cage", retrieved November 24, 2014.

- ↑ Mongan, Elizabeth (1960). Berthe Morisot, Drawings Pastels, Watercolors. New York: Shorewood Publishing Co. p. 20.

- 1 2 3 Stuckey, Charles F.; Scott, William P. (1987). Berthe Morisot: Impressionist. New York: Hudson Hills Press. pp. 187–207. ISBN 0-933920-03-2.

- ↑ Dominique., Rey, Jean (2010). Berthe Morisot. Patry, Sylvie., Morisot, Berthe, 1841-1895., Lalaurie, Louise Rogers. Paris: Flammarion. ISBN 9782080301680. OCLC 646401344.

- ↑ Berthe Morisot : 1841-1895. Mathieu, Marianne., Musée Marmottan. Paris. ISBN 9780300182019. OCLC 830199379.

- ↑ Dominique., Rey, Jean (2010). Berthe Morisot. Patry, Sylvie., Morisot, Berthe, 1841-1895., Lalaurie, Louise Rogers. Paris: Flammarion. ISBN 9782080301680. OCLC 646401344.

- ↑ Dominique., Rey, Jean (2010). Berthe Morisot. Patry, Sylvie., Morisot, Berthe, 1841-1895., Lalaurie, Louise Rogers. Paris: Flammarion. ISBN 9782080301680. OCLC 646401344.

- ↑ Berthe Morisot : 1841-1895. Mathieu, Marianne., Musée Marmottan. Paris. ISBN 9780300182019. OCLC 830199379.

- ↑ Higonnet, Anne (1990). Berthe Morisot. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc. p. 26. ISBN 0-06-016232-5.

- ↑ Dominique., Rey, Jean (2010). Berthe Morisot. Patry, Sylvie., Morisot, Berthe, 1841-1895., Lalaurie, Louise Rogers. Paris: Flammarion. ISBN 9782080301680. OCLC 646401344.

- ↑ Higonnet, Anne (1990). Berthe Morisot. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc. p. 102. ISBN 0-06-016232-5.

- ↑ Dominique., Rey, Jean (2010). Berthe Morisot. Patry, Sylvie., Morisot, Berthe, 1841-1895., Lalaurie, Louise Rogers. Paris: Flammarion. ISBN 9782080301680. OCLC 646401344.

- ↑ Chadwick, Whitney (2012). Women, Art, and Society (Fifth ed.). London: Thames & Hudson Inc. p. 253. ISBN 978-0-500-20405-4.

- ↑ Lewis, M.T. "Book Reviews: Berthe Morisot." Art Journal, vol. 50, no. 3, Fall91, p. 92. EBSCOhost,

- ↑ Harmon, Melissa Burdick. "Monet, Renoir, Degas...Morisot the Forgotten Genius of Impressionism." Biography, vol. 5, no. 6, June 2001, p. 98. EBSCOhost,

- ↑ Chadwick, Whitney (2012). Women, Art, and Society (5th ed.). London: Thames & Hudson Ltd. p. 234. ISBN 978-0-500-20405-4.

- ↑ Higonnet, Anne (1990). Berthe Morisot. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc. p. 139. ISBN 0-06-016232-5.

- ↑ Higonnet, Anne (1990). Berthe Morisot. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc. p. 158. ISBN 0-06-016232-5.

- ↑ "Berthe Morisot | French painter". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-03-29.

- ↑ Valentinovna),, Brodskai︠a︡, N. V. (Natalʹi︠a︡. Impressionism. New York. ISBN 9781780428017. OCLC 778448857.

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 23)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 24)

- ↑ (Bataille Wildenstein, p. 11)

- ↑ (Bataille Wildenstein, p. 12)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 34)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 35)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 40)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 41)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 45)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 46)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 47)

- ↑ Berthe Morisot, Femme et enfant au balcon (On the Balcony), 1871-72, Art Institute of Chicago

- ↑ (Bataille Wildenstein, p. 260)

- ↑ (Bataille Wildenstein, p. 419)

- ↑ Madame Pontillon, descriptif actuel

- ↑ (Bataille Wildenstein, p. 42)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 53)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 51)

- 1 2 (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 56)

- ↑ (Bataille Wildenstein, p. 28)

- ↑ (Bataille Wildenstein, p. 34)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 61)

- 1 2 (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 63)

- ↑ (Bataille Wildenstein, p. 427)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 64)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 65)

- ↑ (Bataille Wildenstein, p. 61)

- ↑ (Bataille Wildenstein, p. 52)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 69)

- ↑ (Bataille Wildenstein, p. 51)

- 1 2 (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 71)

- ↑ (Bataille Wildenstein, p. 73)

- ↑ (Bataille Wildenstein, p. 81)

- ↑ (Bataille Wildenstein, p. 59)

- ↑ (Bataille Wildenstein, p. 64)

- ↑ (Bataille Wildenstein, p. 434)

- ↑ (Bataille Wildenstein, p. 75)

- ↑ (Bataille Wildenstein, p. 78)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 81)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 82)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 83)

- ↑ Robert Rosenblum, Paintings in the Musée D’Orsay, p. 305, Stewart, Tabori & Chang (1989).

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 85)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 91)

- 1 2 (Bataille Wildenstein, p. 112)

- ↑ (Bataille Wildenstein, p. 113)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 95)

- ↑ (Bataille Wildenstein, p. 138)

- ↑ voir La Fable

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 96)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 97)

- ↑ (Bataille Wildenstein, p. 154)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 101)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 98)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 103)

- ↑ aperçu de la toile Meule de foin

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 104)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 105)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 107)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 109)

- ↑ Minneapolis Institute of Art

- ↑ "The Artist's Daughter, Julie, with her Nanny, Berthe Morisot ^ Minneapolis Institute of Art". collections.artsmia.org. Retrieved 2018-02-17.

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 110)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 111)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 115)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 117)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 120)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 122)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 121)

- ↑ (Bataille Wildenstein, p. 197)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 127)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 128)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 129)

- ↑ (Bataille Wildenstein, p. 750)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 131)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 133)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 134)

- ↑ "Berthe Morisot and Julie Manet, Berthe Morisot ^ Minneapolis Institute of Art". collections.artsmia.org. Retrieved 2018-02-17.

- ↑ (Bataille Wildenstein, p. 542)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 142)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 147)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 152)

- ↑ (Bataille Wildenstein, p. 275)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 155)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 165)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 172)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 173)

- ↑ (Stuckey, Scott Lindsay, p. 174)

- ↑ Chadwick, Whitney (2012). Women, Art, and Society (5th ed.). London: Thames & Hudson Ltd. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-500-20405-4.

- ↑ Higonnet, Anne (1990). Berthe Morisot. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc. p. 124. ISBN 0-06-016232-5.

- ↑ Shennan, Margaret (1996). Berthe Morisot: The First Lady of Impressionism. Stroud: Sutton Publishing Limited. p. 173. ISBN 0-7509-1226 X.

- 1 2 Kelly Crow and Mary M. Lane (February 6, 2013), Christie's Breaks World Record Price for Female Artist Wall Street Journal.

- 1 2 Ellen Gamerman and Mary M. Lane (April 18, 2013), Women on the Verge Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ Katya Kazakina (May 14, 2014), Billionaires Help Christie’s to Record $745 Million Sale Bloomberg.

- ↑ Trisha, Managing Editor (17 Nov 2009). "Sneak peek: Elizabeth Kostova's 'The Swan Thieves'". bookpage.com. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- ↑ Truitt, Anne. "A FIRST IMPRESSIONIST". Retrieved 2018-03-29.

- ↑ Harmon, Melissa Burdick. "Monet, Renoir, Degas...Morisot the Forgotten Genius of Impressionism." Biography, vol. 5, no. 6, June 2001, p. 98. EBSCOhost,

Sources

| Wikisource has the text of a 1920 Encyclopedia Americana article about Berthe Morisot. |

- Denvir, B. (2000). The Chronicle of Impressionism: An Intimate Diary of the Lives and World of the Great Artists. London: Thames & Hudson. OCLC 43339405

- Higonnet, Anne (1995). Berthe Morisot. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20156-6

- Turner, J. (2000). From Monet to Cézanne: late 19th-century French artists. Grove Art. New York: St Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-22971-2

- Manet, Julie, Rosalind de Boland Roberts, and Jane Roberts. Growing Up with the Impressionists: The Diary of Julie Manet. London: Sotheby's Publications, 1987

- Shennan, Margaret (1996). Berthe Morisot: The First Lady of Impressionism. Stroud: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-2339-3

External links

|

| |

|

|

- Works by or about Berthe Morisot at Internet Archive

- Edma Morisot, 1865, Berthe Morisot painting at her easel Private collection.

- Berthe Morisot at the WebMuseum

- Biography of Berthe Morisot

- Works by or about Berthe Morisot in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Berthe Morisot in American public collections, on the French Sculpture Census website