Bernstein polynomial

In the mathematical field of numerical analysis, a Bernstein polynomial, named after Sergei Natanovich Bernstein, is a polynomial in the Bernstein form, that is a linear combination of Bernstein basis polynomials.

A numerically stable way to evaluate polynomials in Bernstein form is de Casteljau's algorithm.

Polynomials in Bernstein form were first used by Bernstein in a constructive proof for the Stone–Weierstrass approximation theorem. With the advent of computer graphics, Bernstein polynomials, restricted to the interval [0, 1], became important in the form of Bézier curves.

Definition

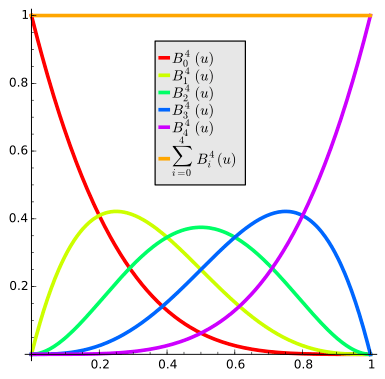

The n + 1 Bernstein basis polynomials of degree n are defined as

where is a binomial coefficient.

The Bernstein basis polynomials of degree n form a basis for the vector space Πn of polynomials of degree at most n.

A linear combination of Bernstein basis polynomials

is called a Bernstein polynomial or polynomial in Bernstein form of degree n.[1]

The coefficients are called Bernstein coefficients or Bézier coefficients.

Example

The first few Bernstein basis polynomials are:

Properties

The Bernstein basis polynomials have the following properties:

- , if or .

- for .

- .

- and where is the Kronecker delta function:

- has a root with multiplicity at point (note: if , there is no root at 0).

- has a root with multiplicity at point (note: if , there is no root at 1).

- The derivative can be written as a combination of two polynomials of lower degree:

- The transformation of the Bernstein Polynomial to monomials is

and by the inverse binomial transformation the reverse transformation is[2]

- The indefinite integral is given by:

- The definite integral is constant for a given

- If

, then

has a unique local maximum on the interval

at

. This maximum takes the value:

- The Bernstein basis polynomials of degree

form a partition of unity:

- By taking the first derivative of

where

, it can be shown that

- The second derivative of

where

can be used to show

- A Bernstein polynomial can always be written as a linear combination of polynomials of higher degree:

Approximating continuous functions

Let ƒ be a continuous function on the interval [0, 1]. Consider the Bernstein polynomial

It can be shown that

uniformly on the interval [0, 1].[3] This is a stronger statement than the proposition that the limit holds for each value of x separately; that would be pointwise convergence rather than uniform convergence. Specifically, the word uniformly signifies that

Bernstein polynomials thus afford one way to prove the Weierstrass approximation theorem that every real-valued continuous function on a real interval [a, b] can be uniformly approximated by polynomial functions over R.[4]

A more general statement for a function with continuous kth derivative is

where additionally

is an eigenvalue of Bn; the corresponding eigenfunction is a polynomial of degree k.

Proof

Suppose K is a random variable distributed as the number of successes in n independent Bernoulli trials with probability x of success on each trial; in other words, K has a binomial distribution with parameters n and x. Then we have the expected value E(K/n) = x.

By the weak law of large numbers of probability theory,

for every δ > 0. Moreover, this relation holds uniformly in x, which can be seen from its proof via Chebyshev's inequality, taking into account that the variance of K/n, equal to x(1-x)/n, is bounded from above by 1/(4n) irrespective of x.

Because ƒ, being continuous on a closed bounded interval, must be uniformly continuous on that interval, one infers a statement of the form

uniformly in x. Taking into account that ƒ is bounded (on the given interval) one gets for the expectation

uniformly in x. To this end one splits the sum for the expectation in two parts. On one part the difference does not exceed ε; this part cannot contribute more than ε. On the other part the difference exceeds ε, but does not exceed 2M, where M is an upper bound for |ƒ(x)|; this part cannot contribute more than 2M times the small probability that the difference exceeds ε.

Finally, one observes that the absolute value of the difference between expectations never exceeds the expectation of the absolute value of the difference, and that E(ƒ(K/n)) is just the Bernstein polynomial Bn(ƒ, x).

See for instance.[5]

See also

Notes

- ↑ G. G. Lorentz (1953) Bernstein Polynomials, University of Toronto Press

- ↑ Mathar, R. J. (2018). "Orthogonal basis function over the unit circle with the minimax property". arXiv:1802.09518. App. B

- ↑ Natanson (1964) p.6

- ↑ Natanson (1964) p.3

- ↑ L. Koralov and Y. Sinai, "Theory of probability and random processes" (second edition), Springer 2007; see page 29, Section "Probabilistic proof of the Weierstrass theorem".

References

- Caglar, Hakan; Akansu, Ali N. (July 1993). "A generalized parametric PR-QMF design technique based on Bernstein polynomial approximation". IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing. 41 (7): 2314–2321. doi:10.1109/78.224242. Zbl 0825.93863.

- Korovkin, P.P. (2001) [1994], "Bernstein polynomials", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- Natanson, I.P. (1964). Constructive function theory. Volume I: Uniform approximation. Translated by Alexis N. Obolensky. New York: Frederick Ungar. MR 0196340. Zbl 0133.31101.

External links

- Bill Casselman, From Bézier to Bernstein, Feature Column from American Mathematical Society

- Kac, M. (1938). "Une remarque sur les polynomes de M. S. Bernstein". Stud. Math. 7: 49–51. doi:10.4064/sm-7-1-49-51.

- Kelisky, Richard Paul; Rivlin, Theodore Joseph (1967). "Iteratives of Bernstein Polynomials". Pac. J. Math. 21 (3): 511. doi:10.2130/pjm.1967.21.511.

- Stark, E. L. (1981). "Bernstein Polynome, 1912-1955". In Butzer, P.L. ISNM60. pp. 443–461. doi:10.1007/978-3-0348-9-369-5_40. ISBN 978-3-0348-9369-5.

- Petrone, Sonia (1999). "Random Bernstein polynomials". Scand. J. Stat. 26 (3): 373–393. doi:10.1111/1467-9469.00155.

- Oruc, Halil; Phillips, Geoerge M. (1999). "A generalization of the Bernstein Polynomials". Proc. Edin. Math. Soc. 42: 403–413. doi:10.1017/S0013091500020332.

- Joy, Kenneth I. (2000). "Bernstein Polynomials" (PDF). from University of California, Davis. Note the error in the summation limits in the first formula on page 9.

- Idrees Bhatti, M.; Bracken, P. (2007). "Solutions of differential equations in a Bernstein Polynomial basis". J. Comp. Appl. Math. 205: 272–280. doi:10.1016/j.cam.2006.05.002.

- Acikgoz, Mehmet; Araci, Serkan (2010). "On the generating function for Bernstein Polynomials". AIP Conf. Proc. 1281: 1141. doi:10.1063/1.3497855.

- Doha, E. H.; Bhrawy, A. H.; Saker, M. A. (2011). "Integrals of Bernstein polynomials: An application for the solution of high even-order differential equations". Appl. Math. Lett. 24: 559–565. doi:10.1016/j.aml.2010.11.013.

- Farouki, Rida T. (2012). "The Bernstein polynomial basis: a centennial retrospective". Comp. Aid. Geom. Des. 29: 379–419. doi:10.1016/j.cagd.2012.03.001.

- Chen, Xiaoyan; Tan, Jieqing; Liu, Zhi; Xie, Jin (2017). "Approximations of functions by a new family of generalized Bernstein operators". J. Math. Ann. Applic. 450: 244–261. doi:10.1016/j.jmaa.2016.12.075.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Bernstein Polynomial". MathWorld.

- This article incorporates material from properties of Bernstein polynomial on PlanetMath, which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License.