Bemidbar (parsha)

Bemidbar, BeMidbar, or B'midbar (בְּמִדְבַּר — Hebrew for "in the desert of" [Sinai], the fifth overall and first distinctive word in the parashah), often called Bamidbar or Bamidbor (בַּמִדְבָּר — Hebrew for "in the desert"), is the 34th weekly Torah portion (פָּרָשָׁה, parashah) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the first in the Book of Numbers. The parashah tells of the census and the priests' duties. It constitutes Numbers 1:1–4:20. The parashah is made up of 7,393 Hebrew letters, 1,823 Hebrew words, and 159 verses, and can occupy about 263 lines in a Torah Scroll (סֵפֶר תּוֹרָה, Sefer Torah).[1] Jews generally read it in May or early June.[2]

Readings

In traditional Sabbath Torah reading, the parashah is divided into seven readings, or עליות, aliyot.[3]

| Rank by Population | Tribe | Population | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Judah | 74,600 | 12.4 |

| 2 | Dan | 62,700 | 10.4 |

| 3 | Simeon | 59,300 | 9.8 |

| 4 | Zebulun | 57,400 | 9.5 |

| 5 | Issachar | 54,400 | 9.0 |

| 6 | Naphtali | 53,400 | 8.8 |

| 7 | Reuben | 46,500 | 7.7 |

| 8 | Gad | 45,650 | 7.5 |

| 9 | Asher | 41,500 | 6.9 |

| 10 | Ephraim | 40,500 | 6.7 |

| 11 | Benjamin | 35,400 | 5.9 |

| 12 | Manasseh | 32,200 | 5.3 |

| TOTAL | 603,550 | 100.0 |

First reading — Numbers 1:1–19

In the first reading (עליה, aliyah), in the wilderness, in the second month of the second year following the Exodus from Egypt, God directed Moses to take a census of the Israelite men age 20 years and up, "all those in Israel who are able to bear arms."[4] In verses 5 to 15 the heads of each of the tribes or army divisions are named.

Second reading — Numbers 1:20–54

In the second reading (עליה, aliyah), the census showed the following populations by tribe:[5]

- Reuben: 46,500

- Simeon: 59,300

- Gad: 45,650

- Judah: 74,600

- Issachar: 54,400

- Zebulun: 57,400

- Ephraim: 40,500

- Manasseh: 32,200

- Benjamin: 35,400

- Dan: 62,700

- Asher: 41,500

- Naphtali: 53,400

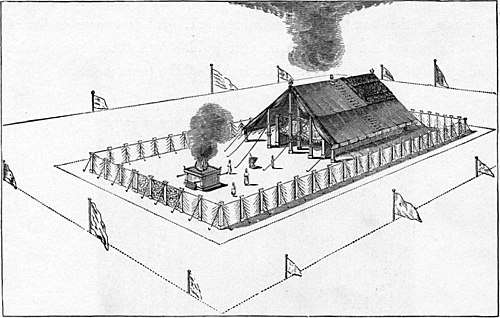

totaling 603,550 in all. God told Moses not to enroll the Levites, but to put them in charge of carrying, assembling, tending to, and guarding the Tabernacle and its furnishings.[6] Any outsider who encroached on the Tabernacle was to be put to death.[7]

| North | ||||||

| Asher | DAN | Naphtali | ||||

| Benjamin | Merari | Issachar | ||||

| West | EPHRAIM | Gershon | THE TABERNACLE | Priests | JUDAH | East |

| Manasseh | Kohath | Zebulun | ||||

| Gad | REUBEN | Simeon | ||||

| South |

Third reading — Numbers 2:1–34

In the third reading (עליה, aliyah), God told Moses that the Israelites were to encamp by tribe as follows:[8]

- around the Tabernacle: Levi

- on the front, or east side: Judah, Issachar, and Zebulun

- on the south: Reuben, Simeon, and Gad

- on the west: Ephraim, Manasseh, and Benjamin

- on the north: Dan, Asher, and Naphtali.

Fourth reading — Numbers 3:1–13

In the fourth reading (עליה, aliyah), God instructed Moses to place the Levites in attendance upon Aaron to serve him and the priests.[9] God took the Levites in place of all the firstborn among the Israelites, whom God consecrated when God smote the firstborn in Egypt.[10]

Fifth reading — Numbers 3:14–39

In the fifth reading (עליה, aliyah), God then told Moses to record by ancestral house and by clan the Levite men from the age of one month up, and he did so.[11] The Levites divided by their ancestral houses, based on the sons of Levi: Gershon, Kohath, and Merari.[12]

| Rank by Population | Division | Population | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kohathites | 8,600 | 38.6 |

| 2 | Gershonites | 7,500 | 33.6 |

| 3 | Merarites | 6,200 | 27.8 |

| Total | 22,300 | 100.0 |

- The Gershonites, numbered 7,500, camped behind the Tabernacle, to the west, and had charge of the Tabernacle, the tent, its covering, the screen for the entrance of the tent, the hangings of the enclosure, the screen for the entrance of the enclosure that surrounded the Tabernacle, and the altar.[13]

- The Kohathites, numbered 8,600, camped along the south side of the Tabernacle, and had charge of the ark, the table, the lampstand, the altars, the sacred utensils, and the screen.[14]

- The Merarites, numbered 6,200, camped along the north side of the Tabernacle, and had charge of the planks of the Tabernacle, its bars, posts, sockets, and furnishings, and the posts around the enclosure and their sockets, pegs, and cords.[15]

- Moses, Aaron, and Aaron's sons (who were also descended from Kohath[16]) camped in front of the Tabernacle, on the east.[17]

The total number of the Levites came to 22,000.[18]

Sixth reading — Numbers 3:40–51

In the sixth reading (עליה, aliyah), God instructed Moses to record every firstborn male of the Israelites aged one month old and upwards, and they came to 22,273.[19] God told Moses to take the 22,000 Levites for God in exchange for all the firstborn among the Israelites, and the Levites' cattle in exchange for the Israelites' cattle.[20] To redeem the 273 Israelite firstborn over and above the number of the Levites, God instructed Moses to take five shekels a head and to give the money to the priests.[21]

Seventh reading — Numbers 4:1–20

In the seventh reading (עליה, aliyah), God then directed Moses and Aaron to take a separate census of the Kohathites between the ages of 30 and 50, who were to perform tasks for the Tent of Meeting.[22] The Kohathites had responsibility for the most sacred objects.[23] The parsha does not state the number of working age Kohathites who were counted.

At the breaking of camp, Aaron and his sons were to take down the Ark, the table of display, the lampstand, and the service vessels, and cover them all with cloths and skins.[24] Only when Aaron and his sons had finished covering the sacred objects would the Kohathites come and lift them.[25] Aaron's son Eleazar had responsibility for the lighting oil, the aromatic incense, the regular meal offering, the anointing oil, and all the consecrated things in the Tabernacle.[26] God charged Moses and Aaron to take care not to let the Kohathites die because they went inside and witnessed the dismantling of the sanctuary.[27]

Readings according to the triennial cycle

Jews who read the Torah according to the triennial cycle of Torah reading read the parashah according to the following schedule:[28]

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016–2017, 2019–2020 ... | 2017–2018, 2020–2021 ... | 2018–2019, 2021–2022 ... | |

| Reading | 1:1–54 | 2:1–3:13 | 3:14–4:20 |

| 1 | 1:1–4 | 2:1–9 | 3:14–20 |

| 2 | 1:5–16 | 2:10–16 | 3:21–26 |

| 3 | 1:17–19 | 2:17–24 | 3:27–39 |

| 4 | 1:20–27 | 2:25–31 | 3:40–43 |

| 5 | 1:28–35 | 2:32–34 | 3:44–51 |

| 6 | 1:36–43 | 3:1–4 | 4:1–10 |

| 7 | 1:44–54 | 3:5–13 | 4:11–20 |

| Maftir | 1:52–54 | 3:11–13 | 4:17–20 |

In inner-biblical interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these Biblical sources:[29]

Numbers chapter 1–2

Three times in this parashah the Torah lists the tribes, and each time the Torah lists the tribes in a different order:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Numbers 1:1–5 | Reuben | Simeon | Judah | Issachar | Zebulun | Ephraim | Manasseh | Benjamin | Dan | Asher | Gad | Naphtali |

| Numbers 1:20–43 | Reuben | Simeon | Gad | Judah | Issachar | Zebulun | Ephraim | Manasseh | Benjamin | Dan | Asher | Naphtali |

| Numbers 2:3–31 | Judah | Issachar | Zebulun | Reuben | Simeon | Gad | Ephraim | Manasseh | Benjamin | Dan | Asher | Naphtali |

Numbers chapters 3–4

Numbers 3:5–4:20 refers to duties of the Levites. Deuteronomy 33:10 reports that Levites taught the law.[30] Deuteronomy 17:9–10 reports that they served as judges.[31] And Deuteronomy 10:8 reports that they blessed God's name. 1 Chronicles 23:3–5 reports that of 38,000 Levite men age 30 and up, 24,000 were in charge of the work of the Temple in Jerusalem, 6,000 were officers and magistrates, 4,000 were gatekeepers, and 4,000 praised God with instruments and song. 1 Chronicles 15:16 reports that King David installed Levites as singers with musical instruments, harps, lyres, and cymbals, and 1 Chronicles 16:4 reports that David appointed Levites to minister before the Ark, to invoke, to praise, and to extol God. And 2 Chronicles 5:12 reports at the inauguration of Solomon's Temple, Levites sang dressed in fine linen, holding cymbals, harps, and lyres, to the east of the altar, and with them 120 priests blew trumpets. 2 Chronicles 20:19 reports that Levites of the sons of Kohath and of the sons of Korah extolled God in song. Eleven Psalms identify themselves as of the Korahites.[32]

In classical rabbinic interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these rabbinic sources from the era of the Mishnah and the Talmud:[33]

Numbers chapter 1

The Rabbis discussed why, in the words of Numbers 1:1, God spoke to Moses "in wilderness." Rava taught that when people open themselves to everyone like a wilderness, God gives them the Torah.[34] Similarly, a Midrash taught that those who do not throw themselves open to all like a wilderness cannot acquire wisdom and Torah. The Sages inferred from Numbers 1:1 that the Torah was given to the accompaniment of fire, water, and wilderness. And the giving of the Torah was marked by these three features to show that as these are free to all people, so are the words of the Torah; as Isaiah 55:1 states, "everyone who thirsts, come for water."[35] Another Midrash taught that if the Torah had been given to the Israelites in the land of Israel, the tribe in whose territory it was given would have said that it had a prior claim to the Torah, so God gave it in the wilderness, so that all should have an equal claim to it. Another Midrash taught that as people neither sow nor till the wilderness, so those who accept the yoke of the Torah are relieved of the yoke of earning a living; and as the wilderness does not yield any taxes from crops, so scholars are free in this world. And another Midrash taught that the Torah was given in the wilderness because they preserve the Torah who keep themselves separate like a wilderness.[36]

The Gemara noted that Numbers 1:1 happened in "the second month, in the second year," while Numbers 9:1 happened "in the first month of the second year," and asked why the Torah presented the chapters beginning at Numbers 1 before Numbers 9, out of chronological order. Rav Menasia bar Tahlifa said in Rav's name that this proved that there is no chronological order in the Torah.[37]

Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak noted that both Numbers 1:1 and Numbers 9:1 begin, "And the Lord spoke to Moses in the wilderness of Sinai," and deduced that just as Numbers 1:1 happened (in the words of that verse) "on the first day of the second month," so too Numbers 9:1 happened at the beginning of the month. And as Numbers 9:1 addressed the Passover offering, which the Israelites were to bring on the 14th of the month, the Gemara concluded that one should expound the laws of a holiday two weeks before the holiday.[37]

A Midrash taught that when God is about to make Israel great, God explicitly states the place, the day, the month, the year, and the era, as Numbers 1:1 says, "in the wilderness of Sinai, in the tent of meeting, on the first day of the second month, in the second year after they were come out of the land of Egypt." The Midrash continued that God then said to the Israelites (rereading Numbers 1:2): "Raise to greatness all the congregation of the children of Israel." (Interpreting "raise the head" — שְׂאוּ אֶת-רֹאשׁ — to mean "raise to greatness.")[38]

A Midrash explained the specificity of Numbers 1:1 with a parable. A king married a wife and did not give her a legal marriage contract. He then sent her away without giving her a bill of divorce. He did the same to a second wife and a third, giving them neither a marriage contract nor a bill of divorce. Then he saw a poor, well-born orphan girl whom he desired to marry. He told his best man (shoshbin) not to deal with her as with the previous ones, as she was well-born, modest in her actions and worthy. The king directed that his aide draw up a marriage contract for her, stating the period of seven years, the year, the month, the day of the month, and the region, in the same way that Esther 2:16 writes about Esther, "So Esther was taken to king Ahasuerus into his house royal in the tenth month, which is the month Tevet, in the seventh year of his reign." So God did not state when God created the generation of the Flood and did not state when God removed them from the world, except insofar as Genesis 7:11 reports, "on the same day were all the fountains of the great deep broken up." The same fate befell the generation of the Dispersal after the Tower of Babel and the generation of Egypt; Scripture does not indicate when God created then or when they passed away. But when Israel appeared, God told Moses that God would not act towards them as God did towards those earlier generations, as they were descendants of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. God instructed that Moses record for them the precise month, day of the month, year, region, and city in which God lifted them up. Therefore, Numbers 1:1 says: "And the Lord spoke to Moses in the wilderness of Sinai," indicating the region; "in the tent of meeting," indicating the province; "in the second year," indicating the precise year; "in the second month," indicating the precise month; "on the first day of the month," indicating the precise day of the month; and "after they were come out of Egypt," indicating the era.[39]

Rabbi Phinehas the son of Idi noted that Numbers 1:2 says, "Lift up the head of all the congregation of the children of Israel," not "Exalt the head" or "Magnify the head," but "Lift up the head," like a man who says to the executioner, "Take off the head of So-and-So." Thus Numbers 1:2 conveys a hidden message with the expression "Lift up the head." If the Israelites were worthy, they would rise to greatness, with the words "Lift up" having the same meaning as in Genesis 40:13 when it says (as Joseph interpreted the chief butler's dream), "Pharaoh shall lift up your head, and restore you to your office." If they were not worthy, they would all die, with the words "Lift up" having the same meaning as in Genesis 40:19 when it says (as Joseph interpreted the chief baker's dream), "Pharaoh shall lift up your head from off you, and shall hang you on a tree."[40]

A Midrash taught that the Israelites were counted on ten occasions:[41] (1) when they went down to Egypt,[42] (2) when they went up out of Egypt,[43] (3) at the first census in Numbers,[44] (4) at the second census in Numbers,[45] (5) once for the banners, (6) once in the time of Joshua for the division of the land of Israel, (7) once by Saul,[46] (8) a second time by Saul,[47] (9) once by David,[48] and (10) once in the time of Ezra.[49]

Rav Aha bar Jacob taught that for the purposes of numbering fighting men (as in Numbers 1:1–3), a man over 60 years of age was excluded just as was one under 20 years of age.[50]

A Midrash explained that Moses numbered the Israelites like a shepherd to whom an owner entrusted a flock by number. When the shepherd came to the end of the shepherd’s time, on returning them, the shepherd had to count them again. When Israel left Egypt, God entrusted the Israelites to Moses by number, as Numbers 1:1 reports, “And the Lord spoke to Moses in the wilderness of Sinai . . . ‘Take the sum of all the congregation of the children of Israel.’” And Exodus 12:37 records that “the children of Israel journeyed from Rameses to Succoth, about 600,000 men on foot,” demonstrating that Moses took responsibility for the Israelites in Egypt by number. When, therefore, Moses was about to depart from the world in the plain of Moab, he returned them to God by number after having them counted in the census reported at Numbers 26:1–51.[51]

Rabbi Isaac taught that it is forbidden to count Israel even for the purpose of fulfilling a commandment, as 1 Samuel 11:8 can be read, "And he numbered them with pebbles (בְּבֶזֶק, be-bezek)." Rav Ashi demurred, asking how Rabbi Isaac knew that the word בֶזֶק, bezek, in 1 Samuel 11:8 means being broken pieces (that is, pebbles). Rav Ashi suggested that perhaps בֶזֶק, Bezek, is the name of a place, as in Judges 1:5, which says, "And they found Adoni-Bezek in Bezek (בְּבֶזֶק, be-bezek)." Rav Ashi argued that the prohibition of counting comes from 1 Samuel 15:4, which can be read, "And Saul summoned the people and numbered them with sheep (טְּלָאִים, telaim)." Rabbi Eleazar taught that whoever counts Israel transgresses a Biblical prohibition, as Hosea 2:1 says, "Yet the number of the children of Israel shall be as the sand of the sea, which cannot be measured." Rav Nahman bar Isaac said that such a person would transgress two prohibitions, for Hosea 2:1 says, "Which cannot be measured nor numbered." Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani reported that Rabbi Jonathan noted a potential contradiction, as Hosea 2:1 says, "Yet the number of the children of Israel shall be as the sand of the sea" (implying a finite number, but Hosea 2:1 also says, "Which cannot be numbered" (implying that they will not have a finite number). The Gemara answered that there is no contradiction, for the latter part of Hosea 2:1 speaks of the time when Israel fulfils God's will, while the earlier part of Hosea 2:1 speaks of the time when they do not fulfill God's will. Rabbi said on behalf of Abba Jose ben Dosthai that there is no contradiction, for the latter part of Hosea 2:1 speaks of counting done by human beings, while the earlier part of Hosea 2:1 speaks of counting by Heaven.[52]

The Rabbis taught in a Baraita that upon entering a barn to measure the new grain one should recite the blessing, "May it be Your will O Lord, our God, that You may send blessing upon the work of our hands." Once one has begun to measure, one should say, "Blessed be the One who sends blessing into this heap." If, however, one first measured the grain and then recited the blessing, then prayer is in vain, because blessing is not to be found in anything that has been already weighed or measured or numbered, but only in a thing hidden from sight.[53]

The Gemara taught that taking a census required atonement. Rabbi Eleazar taught that God told David that David called God an inciter, but God would make David stumble over a thing that even school-children knew, namely, that which Exodus 30:12 says, "When you take the sum of the children of Israel according to their number, then shall they give every man a ransom for his soul into the Lord . . . that there be no plague among them." Forthwith, as 1 Chronicles 21:1 reports, "Satan stood up against Israel," and as 2 Samuel 24:1 reports, "He stirred up David against them saying, ‘Go, number Israel.'" And when David did number them, he took no ransom from them, and as 2 Samuel 24:15 reports, "So the Lord sent a pestilence upon Israel from the morning even to the time appointed." The Gemara asked what 2 Samuel 24:15 meant by "the time appointed." Samuel the elder, the son-in-law of Rabbi Hanina, answered in the name of Rabbi Hanina: From the time of slaughtering the continual offering (at dawn) until the time of sprinkling the blood. Rabbi Johanan said it meant at midday. Reading the continuation of 2 Samuel 24:16, "And He said to the Angel that destroyed the people, ‘It is enough (רַב, rav),'" Rabbi Eleazar taught that God told the Angel to take a great man (רַב, rav) from among them, through whose death many sins could be expiated. So Abishai son of Zeruiah then died, and he was individually equal in worth to the greater part of the Sanhedrin. Reading 1 Chronicles 21:15, "And as he was about to destroy, the Lord beheld, and He repented," the Gemara ask what God beheld. Rav said God beheld Jacob, as Genesis 32:3 reports, "And Jacob said when he beheld them." Samuel said that God beheld the ashes of the ram of Isaac, as Genesis 22:8 says, "God will see for Himself the lamb." Rabbi Isaac Nappaha taught that God saw the atonement money that Exodus 30:16 reports God required Moses to collect. For in Exodus 30:16, God said, "And you shall take the atonement money from the children of Israel, and shalt appoint it for the service of the tent of meeting, that it may be a memorial for the children of Israel before the Lord, to make atonement for your souls.'" (Thus God said that at some future time, the money would provide atonement.) Alternatively, Rabbi Johanan taught that God saw the Temple. For Genesis 22:14 explained the meaning of the name that Abraham gave to the mountain where Abraham nearly sacrificed Isaac to be, "In the mount where the Lord is seen." (Solomon later built the Temple on that mountain, and God saw the merit of the sacrifices there.) Rabbi Jacob bar Iddi and Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani differed on the matter. One said that God saw the atonement money that Exodus 30:16 reports God required Moses to collect from the Israelites, while the other said that God saw the Temple. The Gemara concluded that the more likely view was that God saw the Temple, as Genesis 22:14 can be read to say, "As it will be said on that day, ‘in the mount where the Lord is seen.'"[54]

A Midrash read Numbers 1:2, “Raise the head of the children of Israel,” to teach that God bestows preferment just as a king of flesh and blood bestows preferment.[55]

A Midrash taught that God gave no numbering to any of the other nations of the world, but gave a numbering to Israel, thus confirming God’s words to Israel in Psalm 43:4, “You are precious in My sight.” The Midrash illustrated this by a parable: A king had numerous granaries, all of which contained refuse and rye-grass, so the king was consequently not particular about the quantity of their contents. The king had, however, one particular granary that he perceived to be a fine one. The king thus told a member of his household not to be particular about the quantity of the granaries full of refuse and rye-grass. But as to the fine granary, however, the king directed the member of his household to ascertain the quantity of its contents with particularity. Thus, God was like the king, Israel was like the fine granary, and the member of the king’s house was Moses. Thus God instructed Moses to be particular numbering the Israelites, and Moses did so, as Numbers 1:2 reports that God told Moses, “Take the sum of all the congregation of the children of Israel,” Numbers 2:4 reports, “And his host, and those who were numbered of them,” and Numbers 3:40 reports that God told Moses, “Number all the firstborn males.”[56]

The Gemara deduced from the words "by their families, by their fathers' houses" in Numbers 1:2 that the Torah identifies families by the father's line.[57]

Rabbi Simeon bar Abba in the name of Rabbi Johanan taught that every time Scripture uses the expression “and it was” (vayechi), it intimates the coming of either trouble or joy. If it intimates trouble, there was no trouble to compare with it, and if it itimatres joy, there was no joy to compare with it. Rabbi Samuel bar Nahman made a distinction: In every instance where Scripture employs “and it was” (vayechi), it introduces trouble, while when Scripture employs “and it shall be” (vehayah), it introduces joy. The Sages raised an objection to Rabbi Samuel’s view, noting that to introduce the offerings of the princes, Numbers 7:12 says, “And he that presented his offering . . . was (vayechi),” and surely that was a positive thing. Rabbi Samuel replied that the occasion of the princes’ gifts did not indicate joy, because it was manifest to God that the princes would join with Korah in his dispute (as reported in Numbers 16:1–3). Rabbi Judah ben Rabbi Simon said in the name of Rabbi Levi ben Parta that the case could be compared to that of a member of the palace who committed a theft in the bathhouse, and the attendant, while afraid of disclosing his name, nevertheless made him known by describing him as a certain young man dressed in white. Similarly, although Numbers 16:1–3 does not explicitly mention the names of the princes who sided with Korah in his dispute, Numbers 16:2 nevertheless refers to them when it says, “They were princes of the congregation, the elect men of the assembly, men of renown,” and this recalls Numbers 1:16, “These were the elect of the congregation, the princes of the tribes of their fathers . . . ,” where the text lists their names. They were the “men of renown” whose names were mentioned in connection with the standards; as Numbers 1:5–15 says, “These are the names of the men who shall stand with you, of Reuben, Elizur the son of Shedeur; of Simeon, Shelumiel the son of Zurishaddai . . . .”[58]

The Mekhilta found support in the words "they declared their pedigrees after their families, by their fathers' houses" in Numbers 1:18 for Rabbi Eliezer ha-Kappar's proposition that the Israelites displayed virtue by not changing their names.[59]

Rabbi Judah ben Shalom taught that Numbers 1:49 excluded the Levites from being numbered with the rest of the Israelites for their own benefit, for as Numbers 14:29 reports, "all that were numbered" died in the wilderness, but because the Levites were numbered separately, they entered the land of Israel.[60] A Midrash offered another explanation for why the Levites were not numbered with the Israelites: The Levites were the palace-guard and it would not have been consonant with the dignity of a king that his own legion should be numbered with the other legions.[61]

The Rabbis taught in a Baraita that when the Israelites wandered in the wilderness, the Levitical camp established in Numbers 1:50 served as the place of refuge to which manslayers could flee.[62]

Building upon the prohibition of approaching the holy place in Numbers 1:51, the Gemara taught that a person who unwittingly entered the Temple court without atonement was liable to bring a sin-offering, but a person who entered deliberately incurred the penalty of being cut off from the Jewish people, or karet.[63]

A non-Jew asked Shammai to convert him to Judaism on condition that Shammai appoint him High Priest. Shammai pushed him away with a builder's ruler. The non-Jew then went to Hillel, who converted him. The convert then read Torah, and when he came to the injunction of Numbers 1:51, 3:10, and 18:7 that "the common man who draws near shall be put to death," he asked Hillel to whom the injunction applied. Hillel answered that it applied even to David, King of Israel, who had not been a priest. Thereupon the convert reasoned a fortiori that if the injunction applied to all (non-priestly) Israelites, whom in Exodus 4:22 God had called "my firstborn," how much more so would the injunction apply to a mere convert, who came among the Israelites with just his staff and bag. Then the convert returned to Shammai, quoted the injunction, and remarked on how absurd it had been for him to ask Shammai to appoint him High Priest.[64]

The Gemara relates that once Rabban Gamaliel, Rabbi Eleazar ben Azariah, Rabbi Joshua, and Rabbi Akiva went to Jerusalem after the destruction of the Temple, and just as they came to Mount Scopus, they saw a fox emerging from the Holy of Holies. The first three Rabbis began to cry, but Akiva smiled. The three asked him why he smiled, but Akiva asked them why they wept. Quoting Numbers 1:51, they told him that they wept because a place of which it was once said, "And the common man that draws near shall be put to death," had become the haunt of foxes. Akiva replied that he smiled because this fulfilled the prophecy of Uriah the priest, who prophesied (along with Micah, as reported in Jeremiah 26:18–20) that "Zion shall be plowed as a field, and Jerusalem shall become heaps, and the mountain of the House as the high places of a forest." And Isaiah 8:2 linked Uriah's prophecy with Zechariah's. And Zechariah 8:4 prophesied that "[t]here shall yet old men and old women sit in the broad places of Jerusalem." So the fulfillment of Uriah's prophecy gave Akiva certainty that Zechariah's hopeful prophecy would also find fulfillment. The others then told Akiva that he had comforted them.[65]

Numbers chapter 2

Reading the words of Numbers 2:1, "And the Lord spoke to Moses and Aaron," a Midrash taught that in 18 verses, Scripture places Moses and Aaron (the instruments of Israel's deliverance) on an equal footing (reporting that God spoke to both of them alike),[66] and thus there are 18 benedictions in the Amidah.[67]

Rabbi Eliezer in the name of Rabbi Jose ben Zimra taught that whenever the Israelites were numbered for a proper purpose, they lost no numbers; but whenever they were numbered without a proper purpose, they suffered a diminution. Rabbi Eliezer taught that they were numbered for a proper purpose in connection with the standards (as reported in Numbers 2:2) and the division of the land, but were numbered without a proper purpose (as reported in 2 Samuel 24) in the days of David.[68]

Of the banners (דֶּגֶל, degel) in Numbers 2:2, a Midrash taught that each tribe had a distinctive flag and a different color corresponding to the precious stones on Aaron's breastplate, and that it was from these banners that governments learned to provide themselves with flags of various colors.[69] And another Midrash cited the words "his standard over me is love" in Song of Songs 2:4 to teach that it was with a sign of great love that God organized the Israelites under standards like the ministering angels.[70]

A Midrash used the words "at a distance" in Numbers 2:2 to help define the distance that one may travel on the Sabbath, for the Israelites would need to be close enough to approach the ark on the Sabbath.[71]

A Midrash taught that Korah, Dathan, Abiram, and On all fell in together in their conspiracy, as described in Numbers 16:1, because they lived near each other on the same side of the camp. The Midrash thus taught that the saying, "Woe to the wicked and woe to his neighbor!" applies to Dathan and Abiram. Numbers 3:29 reports that the descendants of Kohath, among whom Korah was numbered, lived on the south side of the Tabernacle. And Numbers 2:10 reports that the descendants of Reuben, among whom Dathan and Abiram were numbered, lived close by, as they also lived on the south side of the Tabernacle.[72]

Rabbi Hama bar Haninah and Rabbi Josiah disagreed about what configuration the Israelites traveled in when they traveled in the Wilderness. Based on Numbers 2:17, "as they encamp, so shall they set forward," one said that they traveled in the shape of a box. Based on Numbers 10:25, "the camp of the children of Dan, which was the rearward of all the camps," the other said that they traveled in the shape of a beam — in a row. Refuting the other's argument, the one who said that they traveled in the shape of a beam read Numbers 2:17, "as they encamp, so shall they set forward," to teach that just as the configuration of their camp was according to God's Word, so the configuration of their journey was by God's Word. While the one who said that they traveled in the shape of a box read Numbers 10:25, "the camp of the children of Dan, which was the rearward of all the camps," to teach that Dan was more populous than the other camps, and would thus travel in the rear, and if anyone would lose any item, the camp of Dan would return it.[73]

The Gemara cited Numbers 2:18–21 to help examine the consequences of Jacob's blessing of Ephraim and Manasseh in Genesis 48:5–6. Rav Aha bar Jacob taught that a tribe that had an inheritance of land was called a "congregation," but a tribe that had no possession was not a "congregation." Thus Rav Aha bar Jacob taught that the tribe of Levi was not called a "congregation." The Gemara questioned Rav Aha's teaching, asking whether there would then be fewer than 12 tribes. Abaye replied quoting Jacob's words in Genesis 48:5: "Ephraim and Manasseh, even as Reuben and Simeon, shall be mine." But Rava interpreted the words "They shall be called after the name of their brethren in their inheritance" in Genesis 48:6 to show that Ephraim and Manasseh were thereafter regarded as comparable to other tribes only in regard to their inheritance of the land, not in any other respect. The Gemara challenged Rava's interpretation, noting that Numbers 2:18–21 mentions Ephraim and Manasseh separately as tribes in connection with their assembling around the camp by their banners. The Gemara replied to its own challenge by positing that their campings were like their possessions, in order to show respect to their banners. The Gemara persisted in arguing that Ephraim and Manasseh were treated separately by noting that they were also separated with regard to their princes. The Gemara responded that this was done in order to show honor to the princes and to avoid having to choose the prince of one tribe to rule over the other. 1 Kings 8:65 indicates that Solomon celebrated seven days of dedication of the Temple in Jerusalem, and Moses celebrated twelve days of dedication of the Tabernacle instead of seven in order to show honor to the princes and to avoid having to choose the prince of one tribe over the other.[74]

Numbers chapter 3

Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani taught in Rabbi Jonathan's name that Numbers 3:1–2 referred to Aaron's sons as descendants of Aaron and Moses because Moses taught them, showing that Scripture ascribes merit to one who teaches Torah to a neighbor's child as if the teacher had begotten the child.[75]

A Midrash noted that Scripture records the death of Nadab and Abihu in numerous places, including Numbers 3:4.[76] This teaches that God grieved for Nadab and Abihu, for they were dear to God. And thus Leviticus 10:3 quotes God to say: "Through them who are near to Me I will be sanctified."[77]

The Mishnah taught that as the Levites exempted the Israelites' firstborn in the wilderness, it followed a fortiori that they should exempt their own animals from the requirement to offer the firstborn.[78] The Gemara questioned whether Numbers 3:45 taught that the Levites' animals exempted the Israelites' animals. Abaye read the Mishnah to mean that if the Levites' animals released the Israelites' animals, it followed a fortiori that the Levites' animals should release their own firstborn. But Rava countered that the Mishnah meant that the Levites themselves exempted the Israelites' firstborn.[79]

Tractate Bekhorot in the Mishnah, Tosefta, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of the firstborn in Numbers 3:11–13.[80]

The Rabbis taught that Numbers 3:15 directed counting the Levites "from a month old and upward" and not earlier because they considered a newborn infant not to be definitely viable, but a child who had lived a month was definitely known to be viable.[81]

A Midrash taught that the Levites camped on the four sides of the Tabernacle in accordance with their duties. The Midrash explained that from the west came snow, hail, cold, and heat, and thus God placed the Gershonites on the west, as Numbers 3:25 indicates that their service was "the tent, the covering thereof, and the screen for the door of the tent of meeting," which could shield against snow, hail, cold, and heat. The Midrash explained that from the south came the dew and rain that bring blessing to the world, and there God placed the Kohathites, who bore the ark that carried the Torah, for as Leviticus 26:3–4 and 15–19 teach, the rains depend on the observance of the Torah. The Midrash explained that from the north came darkness, and thus the Merarites camped there, as Numbers 4:31 indicates that their service was the carrying of wood ("the boards of the tabernacle, and the bars thereof, and the pillars thereof, and the sockets thereof") which Jeremiah 10:8 teaches counteract idolatrous influences when it says, "The chastisement of vanities is wood." And the Midrash explained that from the east comes light, and thus Moses, Aaron, and his sons camped there, because they were scholars and men of pious deeds, bringing atonement by their prayer and sacrifices.[82]

| Levi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kohath | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Amram | Izhar | Hebron | Uzziel | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Miriam | Aaron | Moses | Korah | Nepheg | Zichri | Mishael | Elzaphan | Sithri | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A Midrash taught that Korah took issue with Moses in Numbers 16:1 because Moses had (as Numbers 3:30 reports) appointed Elizaphan the son of Uzziel as prince of the Kohathites, and Korah was (as Exodus 6:21 reports) son of Uzziel's older brother Izhar, and thus had a claim to leadership prior to Elizaphan.[83]

Abaye reported a tradition that a singing Levite who did his colleague's work at the gate incurred the death penalty, as Numbers 3:38 says, “And those who were to pitch before the Tabernacle eastward before the Tent of Meeting toward the sun-rising, were Moses and Aaron, . . . and the stranger who drew near was to be put to death.” Abaye argued that the “stranger” in Numbers 3:38 could not mean a non-priest, for Numbers 3:10 had mentioned that rule already (and Abaye believed that the Torah would not state anything twice). Rather, reasoned Abaye, Numbers 3:38 must mean a “stranger” to a particular job. It was told, however, that Rabbi Joshua ben Hananyia once tried to assist Rabbi Johanan ben Gudgeda (both of whom were Levites) in the fastening of the Temple doors, even though Rabbi Joshua was a singer, not a door-keeper. Rabbi Jonathan found evidence for the Levites’ singing role at Temple services from the warning of Numbers 18:3: “That they [the Levites] do not die, neither they, nor you [Aaron, the priest].” Just as Numbers 18:3 warned about priestly duties at the altar, so (Rabbi Jonathan reasoned) Numbers 18:3 must also address the Levites’ duties in the altar service. It was also taught that the words of Numbers 18:3, “That they [the Levites] do not die, neither they, nor you [Aaron, the priest],” mean that priests would incur the death penalty by engaging in Levites’ work, and Levites would incur the death penalty by engaging in priests’ work, although neither would incur the death penalty by engaging in another's work of their own group (even if they would so incur some penalty for doing so).[84]

A Midrash taught that had Reuben not disgraced himself by his conduct with Bilhah in Genesis 35:22, his descendants would have been worthy of assuming the service of the Levites, for ordinary Levites came to replace firstborn Israelites, as Numbers 3:41 says, "And you shall take the Levites for Me, even the Lord, instead of all the firstborn among the children of Israel."[85]

Numbers chapter 4

A Midrash noted that God ordered the Kohathites counted first in Numbers 4:1 and only thereafter ordered the Gershonites counted in Numbers 4:21, even though Gershon was the firstborn and Scripture generally honors the firstborn. The Midrash taught that Scripture gives Kohath precedence over Gershon because the Kohathites bore the ark that carried the Torah.[86] Similarly, another Midrash taught that God ordered the Kohathites counted first because Kohath was most holy, for Aaron the priest — who was most holy — descended from Kohath, while Gershon was only holy. But the Midrash taught that Gershon did not forfeit his status as firstborn, because Scripture uses the same language, "Lift up the head of the sons of," with regard to Kohath in Numbers 4:2 and with regard to Gershon in Numbers 4:22. And Numbers 4:22 says "they also" with regard to the Gershonites so that one should not suppose that the Gershonites were numbered second because they were inferior to the Kohathites; rather Numbers 4:22 says "they also" to indicate that the Gershonites were also like the Kohathites in every respect, and the Kohathites were placed first in this connection as a mark of respect to the Torah. In other places (for example, Genesis 46:11, Exodus 6:16, Numbers 3:17 and 26:57, and 1 Chronicles 6:1 and 23:6), however, Scripture places Gershon before Kohath.[87]

A Midrash noted that in Numbers 4:1 "the Lord spoke to Moses and Aaron" to direct them to count the Kohathites and in Numbers 4:21 "the Lord spoke to Moses" to direct him to count the Gershonites, but Numbers 4:29 does not report that "the Lord spoke" to direct them to count the Merarites. The Midrash deduced that Numbers 4:29 employed the words "the Lord spoke" so as to give honor to Gershon as the firstborn, and to give him the same status as Kohath. The Midrash then noted that Numbers 4:1 reported that God spoke "to Aaron" with regard to the Kohathites but Numbers 4:21 did not report communication to Aaron with regard to the Gershonites. The Midrash taught that God excluded Aaron from all Divine communications to Moses and that passages that mention Aaron do not report that God spoke to Aaron, but include Aaron's name in sections that concern Aaron to indicate that God spoke to Moses so that he might repeat what he heard to Aaron. Thus Numbers 4:1 mentions Aaron regarding the Kohathites because Aaron and his sons assigned the Kohathites their duties, since (as Numbers 4:15 relates) the Kohathites were not permitted to touch the ark or any of the vessels until Aaron and his sons had covered them. In the case of the Gershonites, however, the Midrash finds no evidence that Aaron personally interfered with them, as Ithamar supervised their tasks, and thus Numbers 4:21 does not mention Aaron in connection with the Gershonites.[88]

A Midrash noted that in Numbers 4:2 and Numbers 4:22, God used the expression "lift up the head" to direct counting the Kohathites and Gershonites, but in Numbers 4:29, God does not use that expression to direct counting the Merarites. The Midrash deduced that God honored the Kohathites on account of the honor of the ark and the Gershonites because Gershon was a firstborn. But since the Merarites neither cared for the ark nor descended from a firstborn, God did not use the expression "lift up the head."[89]

A Midrash noted that Numbers 4:3, 23, 30, 35, 39, 43, and 47 say that Levites "30 years old and upward" did service in the tent of meeting, while Numbers 8:24 says, "from 25 years old and upward they shall go in to perform the service in the work of the tent of meeting." The Midrash deduced that the difference teaches that all those five years, from the age of 25 to the age of 30, Levites served apprenticeships, and from that time onward they were allowed to draw near to do service. The Midrash concluded that a Levite could not enter the Temple courtyard to do service unless he had served an apprenticeship of five years. And the Midrash inferred from this that students who see no sign of success in their studies within a period of five years will never see any. Rabbi Jose said that students had to see success within three years, basing his position on the words "that they should be nourished three years" in Daniel 1:5.[90]

Rav Hamnuna taught that God's decree that the generation of the spies would die in the wilderness did not apply to the Levites, for Numbers 14:29 says, "your carcasses shall fall in this wilderness, and all that were numbered of you, according to your whole number, from 20 years old and upward," and this implies that those who were numbered from 20 years old and upward came under the decree, while the tribe of Levi — which Numbers 4:3, 23, 30, 35, 39, 43, and 47 say was numbered from 30 years old and upward — was excluded from the decree.[91]

The Mishnah taught that one who stole one of the sacred vessels (kisvot) described in Exodus 25:29 and Numbers 4:7 was struck down by zealots on the spot.[92]

The Jerusalem Talmud found support in Numbers 4:18–20 for the proposition in a Baraita that one who dies before age 50 has died a death of karet, of being cut off from the Jewish people. The Gemara there noted that Numbers 4:18–19 spoke of what the Kohathites should avoid doing so "that they may live, and not die." And Numbers 4:20 enjoined that "they shall not go in to see the holy things as they are being covered, lest they die." And since Numbers 8:25 indicates that the Kohathites ceased working near the holy things at age 50, these deaths of karet would have to have occurred before the age of 50.[93] The Babylonian Talmud reports that Rabbah said that deaths between the ages of 50 and 60 are also deaths by karet.[94]

Reading Numbers 4:18, “Cut not off the tribe of the families of the Kohathites from among the Levites,” Rabbi Abba bar Aibu noted that it would have been enough for the text to mention the family of Kohath, and asked why Numbers 4:18 also mentions the whole tribe. Rabbi Abba bar Aibu explained that God (in the words of Isaiah 46:10), “declar[es] the end from the beginning,” and provides beforehand for things that have not yet occurred. God foresaw that Korah, who would descend from the families of Kohath, would oppose Moses (as reported in Numbers 16:1–3) and that Moses would beseech God that the earth should swallow them up (as reflected in Numbers 16:28–30). So God told Moses to note that it was (in the words of Numbers 17:5) “to be a memorial to the children of Israel, to the end that no common man . . . draw near to burn incense . . . as the Lord spoke to him by the hand of Moses.” The Midrash asked why then Numbers 17:5 adds the potentially superfluous words “to him,” and replied that it is to teach that God told Moses that God would listen to his prayer concerning Korah but not concerning the whole tribe. Therefore Numbers 4:18 says, “Cut not off the tribe of the families of the Kohathites from among the Levites.”[95]

In medieval Jewish interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these medieval Jewish sources:[96]

Numbers chapter 1

Reading Numbers 1:1–2 “The Lord spoke . . . in the Sinai Desert . . . on the first of the month . . . ‘Take a census,’” Rashi taught that God counted the Israelites often because they were dear to God. When they left Egypt, God counted them in Exodus 12:37; when many fell because of the sin of the Golden Calf, God counted them in Exodus 32:28 to know the number who survived; when God came to cause the Divine Presence to rest among them, God counted them. On the first of Nisan, the Tabernacle was erected, and on the first of Iyar, God counted them.[97]

Numbers chapter 3

Numbers 3:5–4:20 refers to duties of the Levites. Maimonides and the siddur report that the Levites would recite the Psalm for the Day in the Temple.[98]

Maimonides explained the laws governing the redemption of a firstborn son (פדיון הבן, pidyon haben) in Numbers 3:45–47.[99] Maimonides taught that it is a positive commandment for every Jewish man to redeem his son who is the firstborn of a Jewish mother, as Exodus 34:19 says, "All first issues of the womb are mine," and Numbers 18:15 says, "And you shall surely redeem a firstborn man."[100] Maimonides taught that a mother is not obligated to redeem her son. If a father fails to redeem his son, when the son comes of age, he is obligated to redeem himself.[101] If it is necessary for a man to redeem both himself and his son, he should redeem himself first and then his son. If he only has enough money for one redemption, he should redeem himself.[102] A person who redeems his son recites the blessing: "Blessed are You . . . who sanctified us with His commandments and commanded us concerning the redemption of a son." Afterwards, he recites the shehecheyanu blessing and then gives the redemption money to the Cohen. If a man redeems himself, he should recite the blessing: "Blessed . . . who commanded us to redeem the firstborn" and he should recite the shehecheyanu blessing.[103] The father may pay the redemption in silver or in movable property that has financial worth like that of silver coins.[104] If the Cohen desires to return the redemption to the father, he may. The father should not, however, give it to the Cohen with the intent that he return it. The father must give it to the Cohen with the resolution that he is giving him a present without any reservations.[105] Cohens and Levites are exempt from the redemption of their firstborn, as they served as the redemption of the Israelites' firstborn in the desert.[106] One born to a woman of a priestly or Levite family is exempt, for the matter is dependent on the mother, as indicated by Exodus 13:2 and Numbers 3:12.[107] A baby born by Caesarian section and any subsequent birth are exempt: the first because it did not emerge from the womb, and the second, because it was preceded by another birth.[108] The obligation for redemption takes effect when the baby completes 30 days of life, as Numbers 18:16 says, "And those to be redeemed should be redeemed from the age of a month."[109]

In modern interpretation

Modern scholarly interpretations of material in the parsha include:

Numbers chapter 3

Professor James Kugel of Bar Ilan University saw a conflict over eligibility for the priesthood between the Priestly Source (abbreviated P) in Numbers 3:5–10 and the Deuteronomist (abbreviated D) in Deuteronomy 33:10. Kugel reported that scholars note that P spoke about "the priests, Aaron's sons," because, as far as P was concerned, the only legitimate priests descended from Aaron. P did speak of the Levites as another group of hereditary Temple officials, but according to P, the Levites had a different status: They could not offer sacrifices or perform the other crucial jobs assigned to priests, but served Aaron's descendants as helpers. D, on the other hand, never talked about Aaron's descendants as special, but referred to "the Levitical priests." Kugel reported that many modern scholars interpreted this to mean that D believed that any Levite was a proper priest and could offer sacrifices and perform other priestly tasks, and this may have been the case for some time in Israel. Kugel noted that when Moses blessed the tribe of Levi at the end of his life in Deuteronomy 33:10, he said: "Let them teach to Jacob Your ordinances, and to Israel Your laws; may they place incense before You, and whole burnt offerings on Your altar." And placing incense and whole burnt offerings before God were the quintessential priestly functions. Kugel reported that many scholars believe that Deuteronomy 33:10 dated to a far earlier era, and thus may thus may indicate that all Levites had been considered fit priests at a very early time.[110]

Professor Jacob Milgrom, formerly of the University of California, Berkeley, taught that the verbs used in the laws of the redemption of a firstborn son (פדיון הבן, pidyon haben) in Exodus 13:13–16 and Numbers 3:45–47 and 18:15–16, "natan, kiddesh, he‘evir to the Lord," as well as the use of padah, "ransom," indicate that the firstborn son was considered God's property. Milgrom surmised that this may reflect an ancient rule where the firstborn was expected to care for the burial and worship of his deceased parents. Thus the Bible may be preserving the memory of the firstborn bearing a sacred status, and the replacement of the firstborn by the Levites in Numbers 3:11–13, 40–51; and 8:14–18 may reflect the establishment of a professional priestly class. Milgrom dismissed as without support the theory that the firstborn was originally offered as a sacrifice.[111]

Numbers 3:47 reports that a shekel equals 20 gerahs. This table translates units of weight used in the Bible:[112]

| Unit | Texts | Ancient Equivalent | Modern Equivalent |

|---|---|---|---|

| gerah (גֵּרָה) | Exodus 30:13; Leviticus 27:25; Numbers 3:47; 18:16; Ezekiel 45:12 | 1/20 shekel | 0.6 gram; 0.02 ounce |

| bekah (בֶּקַע) | Genesis 24:22; Exodus 38:26 | 10 gerahs; half shekel | 6 grams; 0.21 ounce |

| pim (פִים) | 1 Samuel 13:21 | 2/3 shekel | 8 grams; 0.28 ounce |

| shekel (שֶּׁקֶל) | Exodus 21:32; 30:13, 15, 24; 38:24, 25, 26, 29 | 20 gerahs; 2 bekahs | 12 grams; 0.42 ounce |

| mina (maneh, מָּנֶה) | 1 Kings 10:17; Ezekiel 45:12; Ezra 2:69; Nehemiah 7:70 | 50 shekels | 0.6 kilogram; 1.32 pounds |

| talent (kikar, כִּכָּר) | Exodus 25:39; 37:24; 38:24, 25, 27, 29 | 3,000 shekels; 60 minas | 36 kilograms; 79.4 pounds |

Commandments

According to Maimonides and Sefer ha-Chinuch, there are no commandments in the parashah.[113]

The Weekly Maqam

In the Weekly Maqam, Sephardi Jews each week base the songs of the services on the content of that week's parashah. For parashah Bamidbar, Sephardi Jews apply Maqam Rast, the maqam that shows a beginning or an initiation of something, because the parashah initiates the Book of Numbers. In the common case where this parashah precedes the holiday of Shavuot, then the maqam that is applied is Hoseni, the maqam that symbolizes the beauty of receiving the Torah.[114]

Haftarah

The haftarah for the parashah is Hosea 2:1–22.[2]

Connection between the haftarah and the parashah

Both the parashah and the haftarah recount Israel's numbers, the parashah in the census,[115] and the haftarah in reference to numbers "like that of the sands of the sea."[116] Both the parashah and the haftarah place Israel in the wilderness (midbar).[117]

The haftarah in the liturgy

Observant Jews recite the concluding lines of the haftarah, Hosea 2:21–22, when they put on tefillin in the morning. They wrap the tefillin strap around their fingers as a groom puts a wedding ring on his betrothed, symbolizing the marriage of God and Israel.[118]

On Shabbat Machar Chodesh

When parashah Bemidbar coincides with Shabbat Machar Chodesh (as it does in 2020, 2023, 2026, and 2027), the haftarah is 1 Samuel 20:18–42.[2]

Notes

- ↑ "Torah Stats — Bemidbar". Akhlah Inc. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

- 1 2 3 “Parashat Bamidbar.” Hebcal. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- ↑ See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Bamidbar/Numbers. Edited by Menachem Davis, pages 2–27. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2007. ISBN 1-4226-0208-7.

- ↑ Numbers 1:1–3.

- ↑ Numbers 1:20–46

- ↑ Numbers 1:47–53.

- ↑ Numbers 1:51.

- ↑ Numbers 2:1–34

- ↑ Numbers 3:5–8.

- ↑ Numbers 3:11–13.

- ↑ Numbers 3:14–16.

- ↑ Numbers 3:17.

- ↑ Numbers 3:21–26.

- ↑ Numbers 3:27–31.

- ↑ Numbers 3:33–37.

- ↑ Exodus 6:18, 20.

- ↑ Numbers 3:38.

- ↑ Numbers 3:39.

- ↑ Numbers 3:40–43.

- ↑ Numbers 3:44–45.

- ↑ Numbers 3:46–51.

- ↑ Numbers 4:1–3.

- ↑ Numbers 3:31, 4:4.

- ↑ Numbers 4:5–14.

- ↑ Numbers 4:15.

- ↑ Numbers 4:16.

- ↑ Numbers 4:17–20.

- ↑ See, e.g., Richard Eisenberg "A Complete Triennial Cycle for Reading the Torah." Proceedings of the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative Movement: 1986–1990, pages 383–418. New York: The Rabbinical Assembly, 2001. ISBN 0-91-6219-18-6.

- ↑ For more on inner-Biblical interpretation, see, e.g., Benjamin D. Sommer. "Inner-biblical Interpretation." In The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition. Edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, pages 1835–41. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014. ISBN 978-0-19-997846-5.

- ↑ See also 2 Chronicles 17:7–9; and 35:3; Nehemiah 8:7–13; and Malachi 2:6–8.

- ↑ See also 1 Chronicles 23:4 and 26:29; 2 Chronicles 19:8–11; and Nehemiah 11:16 (officers)

- ↑ Psalms 42:1; 44:1; 45:1; 46:1; 47:1; 48:1; 49:1; 84:1; 85:1; 87:1; and 88:1.

- ↑ For more on classical rabbinic interpretation, see, e.g., Yaakov Elman. "Classical Rabbinic Interpretation." In The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition. Edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, pages 1859–78.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Nedarim 55a. Babylonia, 6th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Nedarim. Commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 18. Jerusalem: Koren Publishers, 2015. ISBN 978-965-301-579-1.

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah 1:7. 12th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 5, pages 12–13. London: Soncino Press, 1939. ISBN 0-900689-38-2.

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah 19:26. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 6, pages 775–76.

- 1 2 Babylonian Talmud Pesachim 6b. Reprinted in, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Pesaḥim · Part One. Commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 6. Jerusalem: Koren Publishers, 2013. ISBN 965-301-568-0.

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah 1:1. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 5, pages 1–2.

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah 1:5. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 5, pages 11–12.

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah 1:11. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 5, pages 16–18.

- ↑ Midrash Tanhuma, Ki Sisa 9. 6th–7th centuries. Reprinted in, e.g., Metsudah Midrash Tanchuma. Translated and annotated by Avraham Davis; edited by Yaakov Y.H. Pupko. Monsey, New York: Eastern Book Press, 2006.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 10:22.

- ↑ Exodus 12:37.

- ↑ Numbers 1:1–46.

- ↑ Numbers 26:1–65.

- ↑ 1 Samuel 11:8.

- ↑ 1 Samuel 15:4.

- ↑ 2 Samuel 24:9.

- ↑ Ezra 2:64.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Bava Batra 121b.

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah 21:7. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 6, page 834.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Yoma 22b. Reprinted in, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Yoma. Commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 9. Jerusalem: Koren Publishers, 2013. ISBN 978-965-301-570-8.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Taanit 8b. Reprinted in, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Taanit • Megillah. Commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 12. Jerusalem: Koren Publishers, 2014. ISBN 978-965-301-573-9.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 62b. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Elucidated by Yosef Widroff, Mendy Wachsman, Israel Schneider, and Zev Meisels; edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz, volume 2, page 62b3–5. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1997. ISBN 1-57819-601-9.

- ↑ Leviticus Rabbah 18:5. Land of Israel, 5th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Leviticus. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 4, page 233. London: Soncino Press, 1939. ISBN 0-900689-38-2.

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah 4:1. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 6, pages 95–97.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Nazir 49a. Reprinted in, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Nazir. Commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 19. Jerusalem: Koren Publishers, 2015. ISBN 978-965-301-580-7. Babylonian Talmud Bava Batra 109b. Babylonian Talmud Bekhorot 47a. Archived 2010-10-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah 13:5. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 6, pages 513–15.

- ↑ Mekhilta Pisha 5. Land of Israel, late 4th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Mekhilta According to Rabbi Ishmael. Translated by Jacob Neusner. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1988. ISBN 1-55540-237-2. And Mekhilta de-Rabbi Ishmael. Translated by Jacob Z. Lauterbach. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1933, reissued 2004. ISBN 0-8276-0678-8.

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah 3:7. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 5, pages 78–79. See also Numbers Rabbah 1:11–12. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 5, pages 16–19.

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah 1:12. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 5, pages 18.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Makkot 12b.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Menachot 28b. Archived 2010-10-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 31a. Reprinted in, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Shabbat • Part One. Commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 2. Jerusalem: Koren Publishers, 2012. ISBN 978-965-301-564-7.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Makkot 24b.

- ↑ See Exodus 6:13, 7:8, 9:8, 12:1, 12:43, 12:50; Leviticus 11:1, 13:1, 14:33, 15:1; Numbers 2:1, 4:1, 4:17 14:26, 16:20, 19:1, 20:12, 20:23.

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah 2:1. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 5, page 22.

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah 2:17. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 5, pages 54, 56.

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah 2:7. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 5, pages 28–29.

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah 2:3. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 5, page 23.

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah 2:9. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 5, pages 33–34.

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah 18:5. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 6, pages 713–14.

- ↑ Jerusalem Talmud Eruvin 35b. Land of Israel, circa 400 CE. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Yerushalmi. Elucidated by Mordechai Stareshefsky, Mordechai Smilowitz, Avrohom Neuberger, Chaim Ochs, Gershon Hoffman, Abba Zvi Naiman, Binyamin Jacobson, Yehuda Jaffa, and Mendy Wachsman; edited by Chaim Malinowitz, Yisroel Simcha Schorr, and Mordechai Marcus, volume 17, page 35b4. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2014. ISBN 1-4226-0260-5.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Horayot 6b.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 19b.

- ↑ See Leviticus 10:2 and 16:1; Numbers 3:4 and 26:61; and 1 Chronicles 24:2.

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah 2:23. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 5, page 59.

- ↑ Mishnah Bekhorot 1:1. Land of Israel, circa 200 CE. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, pages 787–88. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-300-05022-4. Babylonian Talmud Bekhorot 3b. Archived 2010-10-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Bekhorot 4a. Archived 2010-10-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Mishnah Bekhorot 1:1–9:8. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, pages 787–810. Tosefta Bekhorot 1:1–7:15. Land of Israel, circa 300 CE. Reprinted in, e.g., The Tosefta: Translated from the Hebrew, with a New Introduction. Translated by Jacob Neusner, volume 2, pages 1469–94. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 2002. ISBN 1-56563-642-2. Babylonian Talmud Bekhorot 2a–61a. Archived 2010-10-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah 3:8. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 5, pages 81, 84.

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah 3:12. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 5, pages 89–91.

- ↑ Midrash Tanhuma, Korah 1. Reprinted in, e.g., Metsudah Midrash Tanchuma. Translated and annotated by Avraham Davis; edited by Yaakov Y.H. Pupko.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Arakhin 11b. Archived 2010-11-24 at the Wayback Machine. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Elucidated by Mendy Wachsman, Feivel Wahl, Yosef Davis, Henoch Moshe Levin, Israel Schneider, Yeshayahu Levy, Eliezer Herzka, Dovid Nachfolger, Eliezer Lachman, and Zev Meisels; edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz, volume 67, page 11b. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2004. ISBN 1-57819-650-7.

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah 6:3. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 5.

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah 6:1. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 5, pages 157–58.

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah 6:2. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 5, page 159, 161.

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah 6:5. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 5, pages 168–69.

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah 6:4. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 5, page 166.

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah 6:3. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 5, pages 162–63.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Bava Batra 121b.

- ↑ Mishnah Sanhedrin 9:6. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, page 604. Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 81b.

- ↑ Jerusalem Talmud Bikkurim 11b. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Yerushalmi. Elucidated by Yehuda Jaffa, Chaim Ochs, Michoel Weiner, Mordechai Smilowitz, Abba Zvi Naiman, and Avrohom Neuberger; edited by Chaim Malinowitz, Yisroel Simcha Schorr, and Mordechai Marcus, volume 12. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2007. ISBN 1-4226-0240-0.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Moed Katan 28a.

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah 5:5. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 5, page 148.

- ↑ For more on medieval Jewish interpretation, see, e.g., Barry D. Walfish. "Medieval Jewish Interpretation." In The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition. Edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, pages 1891–1915.

- ↑ Rashi. Commentary. Numbers 1:1. Troyes, France, late 11th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Rashi. The Torah: With Rashi's Commentary Translated, Annotated, and Elucidated. Translated and annotated by Yisrael Isser Zvi Herczeg, volume 4. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1997. ISBN 0-89906-029-3.

- ↑ Maimonides. Mishneh Torah: Hilchot Temidin uMusafim (The Laws of Continual and Additional Offerings), chapter 6, halachah 9. Egypt, circa 1170–1180. Reprinted in, e.g., Mishneh Torah: Sefer Ha'Avodah: The Book of (Temple) Service. Translated by Eliyahu Touger, pages 576–77. New York: Moznaim Publishing, 2007. ISBN 1-885220-57-X. Reuven Hammer. Or Hadash: A Commentary on Siddur Sim Shalom for Shabbat and Festivals, pages 72–78. New York: The Rabbinical Assembly, 2003. ISBN 0-916219-20-8. The Psalms of the Day are Psalms 92, 24, 48, 82, 94, 81, and 93.

- ↑ Maimonides. Mishneh Torah: Hilchot Bikkurim, chapter 11. Egypt, circa 1170–1180. Reprinted in, e.g., Mishneh Torah: Sefer Zeraim: The Book of Agricultural Ordinances. Translated by Eliyahu Touger, pages 688–703. New York: Moznaim Publishing, 2005. ISBN 1-885220-49-9.

- ↑ Maimonides. Mishneh Torah: Hilchot Bikkurim, chapter 11, ¶ 1. Reprinted in, e.g., Mishneh Torah: Sefer Zeraim: The Book of Agricultural Ordinances. Translated by Eliyahu Touger, pages 688–89.

- ↑ Maimonides. Mishneh Torah: Hilchot Bikkurim, chapter 11, ¶ 2. Reprinted in, e.g., Mishneh Torah: Sefer Zeraim: The Book of Agricultural Ordinances. Translated by Eliyahu Touger, pages 690–91.

- ↑ Maimonides. Mishneh Torah: Hilchot Bikkurim, chapter 11, ¶ 3. Reprinted in, e.g., Mishneh Torah: Sefer Zeraim: The Book of Agricultural Ordinances. Translated by Eliyahu Touger, pages 690–91.

- ↑ Maimonides. Mishneh Torah: Hilchot Bikkurim, chapter 11, ¶ 5. Reprinted in, e.g., Mishneh Torah: Sefer Zeraim: The Book of Agricultural Ordinances. Translated by Eliyahu Touger, pages 690–91.

- ↑ Maimonides. Mishneh Torah: Hilchot Bikkurim, chapter 11, ¶ 6. Reprinted in, e.g., Mishneh Torah: Sefer Zeraim: The Book of Agricultural Ordinances. Translated by Eliyahu Touger, pages 690–93.

- ↑ Maimonides. Mishneh Torah: Hilchot Bikkurim, chapter 11, ¶ 8. Reprinted in, e.g., Mishneh Torah: Sefer Zeraim: The Book of Agricultural Ordinances. Translated by Eliyahu Touger, pages 692–93.

- ↑ Maimonides. Mishneh Torah: Hilchot Bikkurim, chapter 11, ¶ 9. Reprinted in, e.g., Mishneh Torah: Sefer Zeraim: The Book of Agricultural Ordinances. Translated by Eliyahu Touger, pages 692–93.

- ↑ Maimonides. Mishneh Torah: Hilchot Bikkurim, chapter 11, ¶ 10. Reprinted in, e.g., Mishneh Torah: Sefer Zeraim: The Book of Agricultural Ordinances. Translated by Eliyahu Touger, pages 692–94.

- ↑ Maimonides. Mishneh Torah: Hilchot Bikkurim, chapter 11, ¶ 16. Reprinted in, e.g., Mishneh Torah: Sefer Zeraim: The Book of Agricultural Ordinances. Translated by Eliyahu Touger, pages 696–97.

- ↑ Maimonides. Mishneh Torah: Hilchot Bikkurim, chapter 11, ¶ 17. Reprinted in, e.g., Mishneh Torah: Sefer Zeraim: The Book of Agricultural Ordinances. Translated by Eliyahu Touger, pages 696–97.

- ↑ James L. Kugel. How To Read the Bible: A Guide to Scripture, Then and Now, pages 313–14. New York: Free Press, 2007. ISBN 0-7432-3586-X.

- ↑ Jacob Milgrom. The JPS Torah Commentary: Numbers: The Traditional Hebrew Text with the New JPS Translation, page 432. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1990. ISBN 0-8276-0329-0.

- ↑ Bruce Wells. "Exodus." In Zondervan Illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary. Edited by John H. Walton, volume 1, page 258. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 2009. ISBN 978-0-310-25573-4.

- ↑ Maimonides. Mishneh Torah. Cairo, Egypt, 1170–1180. Reprinted in Maimonides. The Commandments: Sefer Ha-Mitzvoth of Maimonides. Translated by Charles B. Chavel, 2 volumes. London: Soncino Press, 1967. ISBN 0-900689-71-4. Sefer HaHinnuch: The Book of [Mitzvah] Education. Translated by Charles Wengrov, 4:3. Jerusalem: Feldheim Publishers, 1988. ISBN 0-87306-457-7.

- ↑ See Mark L. Kligman. "The Bible, Prayer, and Maqam: Extra-Musical Associations of Syrian Jews." Ethnomusicology, volume 45 (number 3) (Autumn 2001): pages 443–479. Mark L. Kligman. Maqam and Liturgy: Ritual, Music, and Aesthetics of Syrian Jews in Brooklyn. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2009. ISBN 0814332161.

- ↑ In Numbers 1:1–2:34.

- ↑ Hosea 2:1.

- ↑ Numbers 1:1; Hosea 2:5, 16.

- ↑ The Schottenstein Edition Siddur for Weekdays with an Interlinear Translation. Edited by Menachem Davis, page 9. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2002. ISBN 1-57819-686-8.

Further reading

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these sources:

Ancient

- Shu-ilishu. Ur, 20th Century BCE. Reprinted in, e.g., Douglas Frayne. "Shu-ilishu." In The Context of Scripture, Volume II: Monumental Inscriptions from the Biblical World. Edited by William W. Hallo. New York: Brill, 2000. ISBN 90-04-10618-9. (standards).

Biblical

- Exodus 6:23 (Nahshon son of Amminadab); 13:1–2 (firstborn); 13:12–13 (firstborn); 22:28–29 (firstborn); 30:11–16 (shekel of atonement).

- Numbers 18:15–18 (firstborn); 26:1–65 (census).

- Deuteronomy 15:19–23 (firstborn); 33:6 (Reuben's numbers).

- 2 Samuel 24:1–25.

- Jeremiah 2:2 (in the wilderness); 31:8 (firstborn).

- Ezekiel 1:10 (on four sides).

- Hosea 2:16 (wilderness).

- Psalm 60:9 (Manasseh, Ephraim, Judah); 78:67–68 (Ephriam, Judah); 68:28 (Benjamin, Judah, Zebulun, Naphtali); 80:3 (Ephraim, Benjamin, Manasseh); 119:6 (obeying commandments); 141:2 (incense); 144:1 (able to go to war).

- Ruth 4:18–21. (Nahshon son of Amminadab).

- 1 Chronicles 21:1–30 (census); 1 Chronicles 27:1–24 (enumerating the leaders of Israel).

Early nonrabbinic

- Philo. Who Is the Heir of Divine Things? 24:124. Alexandria, Egypt, early 1st Century CE. Reprinted in, e.g., The Works of Philo: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition. Translated by Charles Duke Yonge, page 286. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 1993. ISBN 0-943575-93-1.

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 3:12:4. Circa 93–94. Reprinted in, e.g., The Works of Josephus: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition. Translated by William Whiston, page 98. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 1987. ISBN 0-913573-86-8.

Classical rabbinic

- Mishnah: Sanhedrin 9:6; Zevachim 14:4; Menachot 11:5; Bekhorot 1:1–9:8. Land of Israel, circa 200 CE. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, pages 604, 731, 757, 788, 790. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-300-05022-4.

- Tosefta: Megillah 3:22; Sotah 7:17, 11:20; Bekhorot 1:1. Land of Israel, circa 300 CE. Reprinted in, e.g., The Tosefta: Translated from the Hebrew, with a New Introduction. Translated by Jacob Neusner, volume 1, pages 538, 650, 864, 882; volume 2, pages 1469–94. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 2002. ISBN 1-56563-642-2.

- Jerusalem Talmud: Bikkurim 11b; Shabbat 76b; Eruvin 35b; Yoma 31a; Megillah 15b, 17b; Yevamot 12a; Sanhedrin 11b. Land of Israel, circa 400 CE. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Yerushalmi. Edited by Chaim Malinowitz, Yisroel Simcha Schorr, and Mordechai Marcus, volumes 12, 15, 17, 21, 26, 29. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2007–2015.

- Mekhilta Pisha 3, 5; Amalek 4; Bahodesh 1. Land of Israel, late 4th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Mekhilta According to Rabbi Ishmael. Translated by Jacob Neusner, volume 1, pages 22, 30; volume 2, pages 36, 41. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1988. ISBN 1-55540-237-2. And Mekhilta de-Rabbi Ishmael. Translated by Jacob Z. Lauterbach, volume 1, pages 18, 25; volume 2, pages 289–90. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1933, reissued 2004. ISBN 0-8276-0678-8.

- Mekhilta of Rabbi Simeon 16:1; 19:2; 47:2; 48:1; 57:1, 3; 76:4; 83:1. Land of Israel, 5th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Mekhilta de-Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai. Translated by W. David Nelson, pages 54, 75, 211–12, 255, 258, 355, 375. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2006. ISBN 0-8276-0799-7.

- Genesis Rabbah 7:2; 53:13; 55:6; 64:8; 94:9; 97 (NV); 97 (MSV); 97:5. Land of Israel, 5th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Genesis. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 1, pages 50, 472, 486; volume 2, pages 578, 876, 898, 934, 942. London: Soncino Press, 1939. ISBN 0-900689-38-2.

- Leviticus Rabbah. Land of Israel, 5th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Leviticus. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 4, pages 16, 21, 232–33, 260, 262, 411, 415, 420–21, 457. London: Soncino Press, 1939. ISBN 0-900689-38-2.

.jpg)

- Babylonian Talmud: Shabbat 31a, 92a, 116a; Pesachim 6b; Yoma 54a, 58a; Chagigah 25a; Yevamot 64a; Nedarim 55a; Nazir 45a, 49a; Kiddushin 69a; Bava Batra 109b, 121b; Sanhedrin 16b–17a, 19b, 36b, 81b, 82b; Makkot 12b, 15a, 24b; Shevuot 15a; Horayot 6b; Zevachim 55a, 61b, 116b, 119b; Menachot 28b, 37b, 95a, 96a; Chullin 69b; Bekhorot 2a, 3b–5a, 13a, 47a, 49a, 51a; Arakhin 11b, 18b; Tamid 26a. Babylonia, 6th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr, Chaim Malinowitz, and Mordechai Marcus, 72 volumes. Brooklyn: Mesorah Pubs., 2006.

- Pesikta de-Rav Kahana 2:8, 4:3, 7:5, 26:9–10. 6th–7th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Pesikta de-Rab Kahana: R. Kahana's Compilation of Discourses for Sabbaths and Festal Days. Translated by William G. Braude and Israel J. Kapstein, 33, 70, 144, 404–06. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1975. ISBN 0-8276-0051-8. And Pesiqta deRab Kahana: An Analytical Translation and Explanation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, volume 1, pages 27, 56, 116; volume 2, pages 136–37. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1987. ISBN 1-55540-072-8 & ISBN 1-55540-073-6.

Medieval

- Saadia Gaon. The Book of Beliefs and Opinions, 2:10, 12. Baghdad, Babylonia, 933. Translated by Samuel Rosenblatt, pages 118, 128. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1948. ISBN 0-300-04490-9.

- Rashi. Commentary. Numbers 1–4. Troyes, France, late 11th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Rashi. The Torah: With Rashi's Commentary Translated, Annotated, and Elucidated. Translated and annotated by Yisrael Isser Zvi Herczeg, volume 4, pages 1–33. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1997. ISBN 0-89906-029-3.

- Rashbam. Commentary on the Torah. Troyes, early 12th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Rashbam's Commentary on Leviticus and Numbers: An Annotated Translation. Edited and translated by Martin I. Lockshin, pages 155–65. Providence: Brown Judaic Studies, 2001. ISBN 1-930675-07-0.

- Judah Halevi. Kuzari. part 2, ¶ 26. Toledo, Spain, 1130–1140. Reprinted in, e.g., Jehuda Halevi. Kuzari: An Argument for the Faith of Israel. Introduction by Henry Slonimsky, page 105. New York: Schocken, 1964. ISBN 0-8052-0075-4.

- Numbers Rabbah 1:1–5:9; 6:2–3, 5–7, 11; 7:2–3; 9:14; 10:1; 12:15–16; 13:5; 14:3–4, 14, 19; 15:17; 18:2–3, 5; 19:3; 21:7. 12th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 5, pages 1–156, 160, 162, 166, 168–71, 177, 180–82, 268–69, 335; volume 6, pages 486, 489, 515, 573, 584, 627, 633, 662, 708, 710–11, 714, 753, 834. London: Soncino Press, 1939. ISBN 0-900689-38-2.

- Abraham ibn Ezra. Commentary on the Torah. Mid-12th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Ibn Ezra's Commentary on the Pentateuch: Numbers (Ba-Midbar). Translated and annotated by H. Norman Strickman and Arthur M. Silver, pages 1–31. New York: Menorah Publishing Company, 1999. ISBN 0-932232-09-4.

- Maimonides. Guide for the Perplexed, part 3, chapter 24. Cairo, Egypt, 1190. Reprinted in, e.g., Moses Maimonides. The Guide for the Perplexed. Translated by Michael Friedländer, page 305. New York: Dover Publications, 1956. ISBN 0-486-20351-4. (wilderness).

- Hezekiah ben Manoah. Hizkuni. France, circa 1240. Reprinted in, e.g., Chizkiyahu ben Manoach. Chizkuni: Torah Commentary. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 3, pages 847–59. Jerusalem: Ktav Publishers, 2013. ISBN 978-1-60280-261-2.

- Nachmanides. Commentary on the Torah. Jerusalem, circa 1270. Reprinted in, e.g., Ramban (Nachmanides): Commentary on the Torah: Numbers. Translated by Charles B. Chavel, volume 4, pages 5–36. New York: Shilo Publishing House, 1975. ISBN 0-88328-009-4.

- Zohar part 1, pages 130a, 200a; part 2, page 85a; part 3, pages 57a, 117a–121a, 177b. Spain, late 13th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., The Zohar. Translated by Harry Sperling and Maurice Simon. 5 volumes. London: Soncino Press, 1934.

- Jacob ben Asher (Baal Ha-Turim). Rimze Ba'al ha-Turim. Early 14th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Baal Haturim Chumash: Bamidbar/Numbers. Translated by Eliyahu Touger; edited and annotated by Avie Gold, volume 4, pages 1349–87. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2003. ISBN 1-57819-131-9.

- Jacob ben Asher. Perush Al ha-Torah. Early 14th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Yaakov ben Asher. Tur on the Torah. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 3, pages 1004–24. Jerusalem: Lambda Publishers, 2005. ISBN 978-965-7108-76-5.

- Isaac ben Moses Arama. Akedat Yizhak (The Binding of Isaac). Late 15th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Yitzchak Arama. Akeydat Yitzchak: Commentary of Rabbi Yitzchak Arama on the Torah. Translated and condensed by Eliyahu Munk, volume 2, pages 683–91. New York, Lambda Publishers, 2001. ISBN 965-7108-30-6.

Modern