Ur

|

𒋀𒀕𒆠 or 𒋀𒀊𒆠 Urim (Sumerian) 𒋀𒀕𒆠 Uru (Akkadian) أور ʾūr'(Arabic) | |

The ruins of Ur, with the Ziggurat of Ur visible in the background | |

Shown within Iraq | |

| Location | Tell el-Muqayyar, Dhi Qar Governorate, Iraq |

|---|---|

| Region | Mesopotamia |

| Coordinates | 30°57′47″N 46°6′11″E / 30.96306°N 46.10306°ECoordinates: 30°57′47″N 46°6′11″E / 30.96306°N 46.10306°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Founded | c. 3800 BC |

| Abandoned | after 500 BC |

| Periods | Ubaid period to Iron Age |

| Cultures | Sumerian |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1853–1854, 1922–1934 |

| Archaeologists | John George Taylor, Charles Leonard Woolley |

| UNESCO World Heritage site | |

| Official name | Ur Archaeological City |

| Part of | Ahwar of Southern Iraq |

| Criteria | Mixed: (iii)(v)(ix)(x) |

| Reference | 1481-006 |

| Inscription | 2016 (40th Session) |

| Area | 71 ha (0.27 sq mi) |

| Buffer zone | 317 ha (1.22 sq mi) |

Ur (/ʊər/; Sumerian: Urim;[1] Sumerian Cuneiform: 𒋀𒀕𒆠 URIM2KI or 𒋀𒀊𒆠 URIM5KI;[2] Akkadian: Uru;[3] Arabic: أور; Hebrew: אור) was an important Sumerian city-state in ancient Mesopotamia, located at the site of modern Tell el-Muqayyar (Arabic: تل المقير) in south Iraq's Dhi Qar Governorate.[4] Although Ur was once a coastal city near the mouth of the Euphrates on the Persian Gulf, the coastline has shifted and the city is now well inland, on the south bank of the Euphrates, 16 kilometres (9.9 miles) from Nasiriyah in modern-day Iraq.[5]

The city dates from the Ubaid period circa 3800 BC, and is recorded in written history as a city-state from the 26th century BC, its first recorded king being Mesannepada. The city's patron deity was Nanna (in Akkadian, Sin), the Sumerian and Akkadian (Assyrian-Babylonian) moon god, and the name of the city is in origin derived from the god's name, URIM2KI being the classical Sumerian spelling of LAK-32.UNUGKI, literally "the abode (UNUG) of Nanna (LAK-32)".[5]

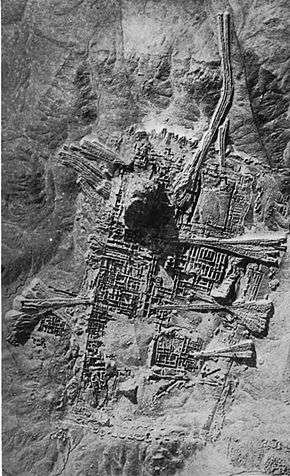

The site is marked by the partially restored ruins of the Ziggurat of Ur, which contained the shrine of Nanna, excavated in the 1930s. The temple was built in the 21st century BC (short chronology), during the reign of Ur-Nammu and was reconstructed in the 6th century BC by Nabonidus, the Assyrian-born last king of Babylon. The ruins cover an area of 1,200 metres (3,900 ft) northwest to southeast by 800 metres (2,600 ft) northeast to southwest and rise up to about 20 metres (66 ft) above the present plain level.[6]

Physical layout

The city, said to have been planned by Ur-Nammu, was apparently divided into neighborhoods, with merchants living in one quarter, artisans in another. There were streets both wide and narrow, and open spaces for gatherings. Many structures for water resource management and flood control are in evidence.[7]

Houses were constructed from mudbricks and mud plaster. In major buildings, the masonry was strengthened with bitumen and reeds. For the most part, foundations are all that remain today. People were often buried (separately and alone; sometimes with jewellery, pots, and weapons) in chambers or shafts beneath the house floors.[7]

Ur was surrounded by sloping ramparts 8 metres high and 25–25 metres wide, bordered in some places by a brick wall. Elsewhere, buildings were integrated into the ramparts. The Euphrates river complemented these fortifications on the city's western side.[7]

Society and culture

Archaeological discoveries have shown unequivocally that Ur was a major Sumero-Akkadian urban center on the Mesopotamian plain. Especially the discovery of the Royal Tombs have confirmed its splendour. These tombs, which date to the Early Dynastic IIIa period (approximately in the 25th or 24th century BC), contained immense amounts of luxury items made out of precious metals, and semi-precious stones, all of which would have required importation from long distances (Ancient Iran, Afghanistan, India, Asia Minor, the Levant and the Persian Gulf).[6] This wealth, unparalleled up to then, is a testimony of Ur's economic importance during the Early Bronze Age.[8]

Archaeological research of the region has also contributed greatly to our understanding of the landscape and long-distance interactions that took place during these ancient times. Ur was a major port on the Persian Gulf, which extended much further inland than it does today, and controlled much of the trade into Mesopotamia. Imports to Ur came from many parts of the world. The imported objects include precious metals such as gold and silver, and semi-precious stones, namely lapis lazuli and carnelian.[7]

It is thought that Ur had a stratified social system including slaves (captured foreigners), farmers, artisans, doctors, scribes, priests. High-ranking priests apparently enjoyed great luxury and lived in mansions.[7]

Tens of thousands of cuneiform texts, including contracts, business records, and court documents, record the city's complex economic and legal systems. These texts have been recovered from temples, the palace, and individual houses.[7]

Music

Excavation in the old city of Ur in 1929 revealed the instrument "Lyres" similar to the modern harps in the shape of bull, and eleven strings.[9]

History

Prehistory

When Ur was founded, the Persian Gulf's water level was two-and-a-half metres higher than it is today. Ur is therefore thought to have had marshy surroundings, and used canals only for transportation, not for irrigation. Fish, birds, tubers, and reeds might have supported Ur economically without the need for an agricultural revolution sometimes hypothesized as a prerequisite to urbanization.[10][11]

Archaeologists have discovered the evidence of an early occupation at Ur during the Ubaid period (ca. 6500 to 3800 BC). These early levels were sealed off with a sterile deposit of soil that was interpreted by excavators of the 1920s as evidence for the Great Flood of the Book of Genesis and Epic of Gilgamesh. It is now understood that the South Mesopotamian plain was exposed to regular floods from the Euphrates and the Tigris rivers, with heavy erosion from water and wind, which may have given rise to the Mesopotamian and derivative Biblical Great Flood stories.[12] The further occupation of Ur only becomes clear during its emergence in the third millennium BC (although it must already have been a growing urban center during the fourth millennium). The third millennium BC is generally described as the Early Bronze Age of Mesopotamia, which ends approximately after the demise of the Third Dynasty of Ur in the 21st century BC.

Third millennium BC (Early Bronze Age)

There are two main sources informing scholars about the importance of Ur during the Early Bronze Age. The first is a large body of cuneiform documents, mostly from the empire of the so-called Third Dynasty of Ur (also known as the Neo-Sumerian Empire), at the very end of the third millennium. This was the most centralized bureaucratic state the world had yet known. Concerning the earlier centuries, the Sumerian King List provides a tentative political history of ancient Sumer. So far evidence for the earliest periods of the Early Bronze Age in Mesopotamia is very limited. Mesannepada is the first king mentioned in the Sumerian King List, and appears to have lived in the 26th century BC. That Ur was an important urban centre already then seems to be indicated by a type of cylinder seal called the City Seals. These seals contain a set of proto-cuneiform signs which appear to be writings or symbols of the name of city-states in ancient Mesopotamia. Many of these seals have been found in Ur, and the name of Ur is prominent on them.[13]

Ur came under the control of the Semitic-speaking Akkadian Empire founded by Sargon the Great between the 24th and 22nd centuries BC. This was a period when the Semitic-speaking Akkadians, who had entered Mesopotamia in approximately 3000 BC, gained ascendancy over the Sumerians, and indeed much of the ancient Near East.

After the fall of the Akkadian Empire in the mid-22nd century BC, southern Mesopotamia came to be ruled for a few decades by the Gutians, a language isolate-speaking barbarian people originating in the Zagros Mountains to the northeast of Mesopotamia, while the Assyrian branch of the Akkadian speakers reasserted their independence in the north of Mesopotamia.

Ur III

The third dynasty was established when the king Ur-Nammu came to power, ruling between ca. 2047 BC and 2030 BC. During his rule, temples, including the Ziggurat of Ur, were built, and agriculture was improved through irrigation. His code of laws, the Code of Ur-Nammu (a fragment was identified in Istanbul in 1952) is one of the oldest such documents known, preceding the Code of Hammurabi by 300 years. He and his successor Shulgi were both deified during their reigns, and after his death he continued as a hero-figure: one of the surviving works of Sumerian literature describes the death of Ur-Nammu and his journey to the underworld.[14]

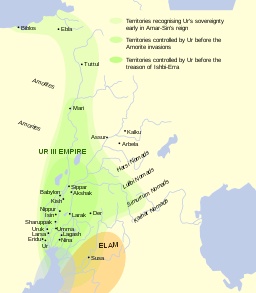

Ur-Nammu was succeeded by Shulgi, the greatest king of the Third Dynasty of Ur, who solidified the hegemony of Ur and reformed the empire into a highly centralized bureaucratic state. Shulgi ruled for a long time (at least 42 years) and deified himself halfway through his rule.[15]

The Ur empire continued through the reigns of three more kings with Semitic Akkadian names,[12] Amar-Sin, Shu-Sin, and Ibbi-Sin. It fell around 1940 BC to the Elamites in the 24th regnal year of Ibbi-Sin, an event commemorated by the Lament for Ur.[16][17]

According to one estimate, Ur was the largest city in the world from c. 2030 to 1980 BC. Its population was approximately 65,000 (or 0.1 per cent share of global population then).[18]

Later Bronze Age

The city of Ur lost its political power after the demise of the Third Dynasty of Ur. Nevertheless, its important position which kept on providing access to the Persian Gulf ensured the ongoing economic importance of the city during the second millennium BC. The splendour of the city, the might of the empire, the greatness of king Shulgi, and undoubtedly the efficient propaganda of the state endured throughout Mesopotamian history. Shulgi was a well known historical figure for at least another two thousand years, while historical narratives of the Mesopotamian societies of Assyria and Babylonia kept names, events, and mythologies in remembrance. The city came to be ruled by the first dynasty (Amorite) of Babylonia which rose to prominence in southern Mesopotamia in the 18th century BC. After the fall of Hammurabi's short lived Babylonian Empire, it later became a part of the native Akkadian ruled Sealand Dynasty for over 270 years, and was reconquered into Babylonia by the successors of the Amorites, the Kassites in the 16th century BC. During the Kassite Dynastic period Ur, along with the rest of Babylonia, came under sporadic control of the Elamites and the Middle Assyrian Empire, the latter of which straddled the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age periods between the early 14th century BC and mid 11th century BC.

Iron Age

The city, along with the rest of southern Mesopotamia and much of the Near East, Asia Minor, North Africa and southern Caucasus, fell to the north Mesopotamian Neo-Assyrian Empire from the 10th to late 7th centuries BC. From the end of the 7th century BC Ur was ruled by the so-called Chaldean Dynasty of Babylon. In the 6th century BC there was new construction in Ur under the rule of Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon. The last Babylonian king, Nabonidus (who was Assyrian-born and not a Chaldean), improved the ziggurat. However, the city started to decline from around 530 BC after Babylonia fell to the Persian Achaemenid Empire, and was no longer inhabited by the early 5th century BC.[12] The demise of Ur was perhaps owing to drought, changing river patterns, and the silting of the outlet to the Persian Gulf.

Identification with Biblical Ur

Ur is likely the city of Ur Kasdim mentioned in the Book of Genesis as the birthplace of the Jewish, Christian and Muslim patriarch Abraham (Ibrahim in Arabic), traditionally believed to have lived some time in the 2nd millennium BC.[19][20][21] There are however conflicting traditions and scholarly opinions identifying Ur Kasdim with the sites of Sanliurfa, Urkesh, Urartu or Kutha.

Ur is mentioned four times in the Torah or Old Testament, with the distinction "of the Kasdim/Kasdin"—traditionally rendered in English as "Ur of the Chaldees". The Chaldeans had settled in the vicinity by around 850 BC, but were not extant anywhere in Mesopotamia during the 2nd millennium BC period when Abraham is traditionally held to have lived. The Chaldean dynasty did not rule Babylonia (and thus become the rulers of Ur) until the late 7th century BC, and held power only until the mid 6th century BC. The name is found in Genesis 11:28, Genesis 11:31, and Genesis 15:7. In Nehemiah 9:7, a single passage mentioning Ur is a paraphrase of Genesis. (Nehemiah 9:7)

The Book of Jubilees states that Ur was founded in 1688 Anno Mundi (year of the world) by 'Ur son of Kesed, presumably the offspring of Arphaxad, adding that in this same year wars began on Earth.

- "And 'Ur, the son of Kesed, built the city of 'Ara of the Chaldees, and called its name after his own name and the name of his father." (i.e., Ur Kasdim) (Jubilees 11:3).[22]

Archaeology

_(14767185992).jpg)

In 1625, the site was visited by Pietro Della Valle, who recorded the presence of ancient bricks stamped with strange symbols, cemented together with bitumen, as well as inscribed pieces of black marble that appeared to be seals.

European archaeologists did not identify Tell el-Muqayyar as the site of Ur until Henry Rawlinson successfully deciphered some bricks from that location, brought to England by William Loftus in 1849.[23]

The site was first excavated in 1853 and 1854, on behalf of the British Museum and with instructions from the Foreign Office, by John George Taylor, British vice consul at Basra from 1851 to 1859.[24][25][26] Taylor uncovered the Ziggurat of Ur and a structure with an arch later identified as part of the "Gate of Judgment".[27]

In the four corners of the ziggurat's top stage, Taylor found clay cylinders bearing an inscription of Nabonidus (Nabuna`id), the last king of Babylon (539 BC), closing with a prayer for his son Belshar-uzur (Bel-ŝarra-Uzur), the Belshazzar of the Book of Daniel. Evidence was found of prior restorations of the ziggurat by Ishme-Dagan of Isin and Shu-Sin of Ur, and by Kurigalzu, a Kassite king of Babylon in the 14th century BC. Nebuchadnezzar also claims to have rebuilt the temple.

Taylor further excavated an interesting Babylonian building, not far from the temple, part of an ancient Babylonian necropolis. All about the city he found abundant remains of burials of later periods. Apparently, in later times, owing to its sanctity, Ur became a favorite place of sepulchres, so that even after it had ceased to be inhabited, it continued to be used as a necropolis.

Typical of the era, his excavations destroyed information and exposed the tell. Natives used the now loosened, 4,000-year-old bricks and tile for construction for the next 75 years, while the site lay unexplored,[28] the British Museum having decided to prioritize archaeology in Assyria.[27]

After Taylor's time, the site was visited by numerous travelers, almost all of whom have found ancient Babylonian remains, inscribed stones and the like, lying upon the surface. The site was considered rich in remains, and relatively easy to explore. After some soundings were made in 1918 by Reginald Campbell Thompson, H. R. Hall worked the site for one season for the British Museum in 1919, laying the groundwork for more extensive efforts to follow.[29][30]

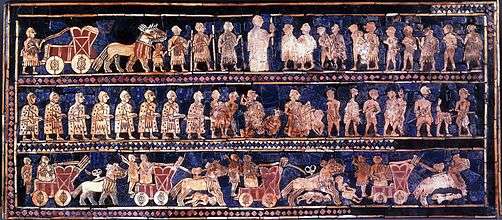

Excavations from 1922 to 1934 were funded by the British Museum and the University of Pennsylvania and led by the archaeologist Sir Charles Leonard Woolley.[31][28][32] A total of about 1,850 burials were uncovered, including 16 that were described as "royal tombs" containing many valuable artifacts, including the Standard of Ur. Most of the royal tombs were dated to about 2600 BC. The finds included the unlooted tomb of a queen thought to be Queen Puabi[33]—the name is known from a cylinder seal found in the tomb, although there were two other different and unnamed seals found in the tomb. Many other people had been buried with her, in a form of human sacrifice. Near the ziggurat were uncovered the temple E-nun-mah and buildings E-dub-lal-mah (built for a king), E-gi-par (residence of the high priestess) and E-hur-sag (a temple building). Outside the temple area, many houses used in everyday life were found. Excavations were also made below the royal tombs layer: a 3.5-metre-thick (11 ft) layer of alluvial clay covered the remains of earlier habitation, including pottery from the Ubaid period, the first stage of settlement in southern Mesopotamia. Woolley later wrote many articles and books about the discoveries.[34] One of Woolley's assistants on the site was the archaeologist Max Mallowan. The discoveries at the site reached the headlines in mainstream media in the world with the discoveries of the Royal Tombs. As a result, the ruins of the ancient city attracted many visitors. One of these visitors was the already famous Agatha Christie, who as a result of this visit ended up marrying Max Mallowan.

During this time the site was accessible from the Baghdad–Basra railway, from a stop called "Ur Junction".[35]

When the Royal Tombs at Ur were first discovered, they had no idea how big they were. They started by digging two trenches in the middle of the desert to see if they could find anything that would allow them to keep digging. They originally split into two teams. Team A and team B. Both teams spent the first few months digging a trench and had found evidence of burial grounds by collecting small pieces of golden jewelry and pottery. This was called at the time the "gold trench"[36] At this time, the first season of digging had come to a close, and Woolley returned to England. In Autumn, Woolley returned and continued to dig into the second season. By the end of the second season, he had uncovered a courtyard[37] surrounded by many rooms.[38] In their third season of digging they had uncovered their biggest find yet, a building that was believed to have been built by the orders of the king, and the second building to be where the high priestess lived. As the fourth and fifth season came to a close, they had discovered so many items, that most of their time was now spent recording the objects they found instead of actually digging objects. They had found many items from gold jewelry to clay pots and stones. There were a few Lyres that were inside of the tombs as well. One of the most significant objects that was discovered was the Standard of Ur. At the end of their sixth season they had excavated 1850 burials and deemed 17 of them to be "Royal Tombs".[39] Woolley had finished his work excavating the Royal Tombs of UR in 1934. Inside princess Puabi's tomb, there was a chest in the middle of the room. Underneath that chest was a hole in the ground that led to what was called the "King's grave" PG-789. It was believed to be the kings grave because it was buried next to the queen. In the "King's Grave" were 63 attendants who were all equipped with copper helmets and swords. It is thought to be his army buried with him. Another large room was uncovered, PG-1237, called the "Great death pit".[40] This large room had 74 bodies, 68 of which were women. There were only two artifacts in the tomb, both of which were Lyres.

Most of the treasures excavated at Ur are in the British Museum and the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. At the Penn Museum the exhibition "Iraq's Ancient Past",[41] which includes many of the most famous pieces from the Royal Tombs, opened to visitors in late Spring 2011. Previously, the Penn Museum had sent many of its best pieces from Ur on tour in an exhibition called "Treasures From the Royal Tombs of Ur." It traveled to eight American museums, including those in Cleveland, Washington and Dallas, ending the tour at the Detroit Institute of Art in May 2011.

In 2009, an agreement was reached for a joint University of Pennsylvania and Iraqi team to resume archaeological work at the site of Ur.[42]

Archaeological remains

Though some of the areas that were cleared during modern excavations have sanded over again, the Great Ziggurat is fully cleared and stands as the best-preserved and most visible landmark at the site.[43] The famous Royal tombs, also called the Neo-Sumerian Mausolea, located about 250 metres (820 ft) south-east of the Great Ziggurat in the corner of the wall that surrounds the city, are nearly totally cleared. Parts of the tomb area appear to be in need of structural consolidation or stabilization.

There are cuneiform (Sumerian writing) on many walls, some entirely covered in script stamped into the mud-bricks. The text is sometimes difficult to read, but it covers most surfaces. Modern graffiti has also found its way to the graves, usually in the form of names made with coloured pens (sometimes they are carved). The Great Ziggurat itself has far more graffiti, mostly lightly carved into the bricks. The graves are completely empty. A small number of the tombs are accessible. Most of them have been cordoned off. The whole site is covered with pottery debris, to the extent that it is virtually impossible to set foot anywhere without stepping on some. Some have colours and paintings on them. Some of the "mountains" of broken pottery are debris that has been removed from excavations. Pottery debris and human remains form many of the walls of the royal tombs area.

In May 2009, the United States Army returned the Ur site to the Iraqi authorities, who hope to develop it as a tourist destination.[44]

Preservation

Since 2009, the non-profit organization Global Heritage Fund (GHF) has been working to protect and preserve Ur against the problems of erosion, neglect, inappropriate restoration, war and conflict. GHF's stated goal for the project is to create an informed and scientifically grounded Master Plan to guide the long-term conservation and management of the site, and to serve as a model for the stewardship of other sites.[45]

Since 2013, the institution for Development Cooperation of the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs DGCS[46] and the SBAH, the State Board of Antiquities and Heritage of the Iraqi Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, have started a cooperation project for "The Conservation and Maintenance of Archaeological site of UR". In the framework of this cooperation agreement, the executive plan, with detailed drawings, is in progress for the maintenance of the Dublamah Temple (design concluded, works starting), the Royal Tombs—Mausolea 3rd Dynasty (in progress)—and the Ziqqurat (in progress). The first updated survey in 2013 has produced a new aerial map derived by the flight of a UAV (unmanned aerial vehicle) operated in March 2014. This is the first high-resolution map, derived from more than 100 aerial photograms, with an accuracy of 20 cm or less. A preview of the ORTHO-PHOTOMAP of Archaeological Site of UR is available online. [47]

Tal Abu Tbeirah

Since 2012, a joint team of Italian and Iraqi archaeologists led by Franco D'Agostino have been excavating at Tal Abu Tbeirah, located 15 kilometers east of Ur and 7 kilometers south of Nasariyah.[48][49][50] The site, about 45 hectares in area, appears to have been a harbor and trading center associated with Ur in the later half of the 3rd Millenium BC.[51]

See also

Notes

- ↑ S. N. Kramer (1963). The Sumerians, Their History, Culture, and Character. University of Chicago Press, pages 28 and 298.

- ↑ Literal transliteration: Urim2 = ŠEŠ. ABgunu = ŠEŠ.UNUG (𒋀𒀕) and Urim5 = ŠEŠ.AB (𒋀𒀊), where ŠEŠ=URI3 (The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature.)

- ↑ The Cambridge Ancient History: Prolegomena & Prehistory. Vol. 1, Part 1. p. 149. Accessed 15 Dec 2010.

- ↑ Tell el-Muqayyar in Arabic Tell means "mound" or "hill" and Muqayyar means "built of bitumen." Muqayyar is variously transcribed as Mugheir, Mughair, Moghair, etc.

- 1 2 Erich Ebeling, Bruno Meissner, Dietz Otto Edzard (1997). Meek - Mythologie. Reallexikon der Assyriologie. (in German) p. 360 (of 589 pages). ISBN 978-3-11-014809-1.

- 1 2 Zettler, R.L. and Horne, L. (eds.) 1998. Treasures from the Royal Tombs of Ur, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Joan Goodnick Westenholz, "Ur – Capital of Sumer"; in Royal Cities of the Biblical World, ed. Joan Goodnick Westenholz; Bible Lands Museum Jerusalem, 1996. ISBN 965-7027-01-2

- ↑ Aruz, J. [ed.] (2003). Art of the First Cities. The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

- ↑ Klimczak, Natalia. "Bask in the Beauty and Melody of the Ancient Mesopotamian Lyres of Ur". Ancient Origins. Retrieved 2018-01-13.

- ↑ Jennifer R. Pournelle, "KLM to CORONA: A Bird's Eye View of Cultural Ecology and Early Mesopotamian Urbanization"; in Settlement and Society: Essays Dedicated to Robert McCormick Adams ed. Elizabeth C. Stone; Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, UCLA, and Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, 2007.

- ↑ Crawford 2015, p. 5.

- 1 2 3 Georges Roux - Ancient Iraq

- ↑ Matthews, R.J. (1993). Cities, Seals and Writing: Archaic Seal Impressions from Jemdet Nasr and Ur, Berlin.

- ↑ Amélie Kuhrt (1995). The Ancient Near East: C.3000-330 B.C. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-16762-0.

- ↑ Potts, D. T. (1999). The Archaeology of Elam. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 132. ISBN 0-521-56496-4. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ↑ Ur III Period (2112–2004 BC) by Douglas Frayne, University of Toronto Press, 1997, ISBN 0-8020-4198-1

- ↑ Dahl, Jacob Lebovitch (2003). The ruling family of Ur III Umma. A Prosopographical Analysis of an Elite Family in Southern Iraq 4000 Years ago (PDF). UCLA dissertation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-05-12.

- ↑ "What Were the Largest Cities Throughout History?". Geography.about.com. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- ↑ Salaheddin, Sinan (April 4, 2013). "Home of Abraham, Ur, unearthed by archaeologists in Iraq". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- ↑ McLerran, Dan (June 23, 2011). "Birthplace of Abraham Gets a New Lease on Life". Popular Archaeology. 3. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Journey of Faith". National Geographic Magazine. May 15, 2012. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Book of Jubilees: The Book of Jubilees: The History of the Patriarchs from Reu to Abraham; the Corruption of the Human Race (xi. 1-15)". Sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- ↑ Crawford 2015, p. 3.

- ↑ J.E. Taylor, "Notes on the Ruins of Muqeyer", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, vol. 15, pp. 260-276, 1855.

- ↑ JE Taylor, "Notes on Abu Shahrein and Tel-el-Lahm", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, vol. 15, pp. 404-415, 1855. [In the relevant publications he is erroneously listed as J. E. Taylor].

- ↑ E. Sollberger, "Mr. Taylor in Chaldaea", Anatolian Studies, vol. 22, pp. 129-139, 1972.

- 1 2 Crawford 2015, p. 4.

- 1 2 Leonard Woolley, Excavations at Ur: A Record of Twelve Years' Work, Apollo, 1965, ISBN 0-8152-0110-9.

- ↑ H. R. Hall, "The Excavations of 1919 at Ur, el-'Obeid, and Eridu, and the History of Early Babylonia", Man, Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 25, pp. 1-7, 1925.

- ↑ H. R. Hall, "Ur and Eridu: The British Museum Excavations of 1919", Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, vol. 9, no. 3/4, pp. 177-195, 1923.

- ↑ Leonard Woolley, Ur: The First Phases, Penguin, 1946.

- ↑ Leonard Woolley and P. R. S. Moorey, Ur of the Chaldees: A Revised and Updated Edition of Sir Leonard Woolley's Excavations at Ur, Cornell University Press, 1982, ISBN 0-8014-1518-7.

- ↑ Queen Puabi is also written Pu-Abi and formerly transcribed as Shub-ab.

- ↑ Beck, Roger B.; Linda Black; Larry S. Krieger; Phillip C. Naylor; Dahia Ibo Shabaka (1999). World History: Patterns of Interaction. Evanston, IL: McDougal Littell. ISBN 0-395-87274-X.

- ↑ Crawford 2015. p. 5. "It used to be close to the Basra to Baghdad railway, part of the proposed Berlin to Basra line that was never completed. It was possible to get off the train from Baghdad at the grandly named Ur Junction, where a branch line turned off to Nasariyah, and drive a mere two miles across the desert to the site itself, but the station was closed sometime after the Second World War, leaving a long, hot journey in a four-wheeled vehicle as the only option."

- ↑ "gold trench".

- ↑ courtyard

- ↑ "The Royal Tombs of Ur - Story". Mesopotamia.co.uk. Retrieved 2016-12-04.

- ↑ Royal Tombs

- ↑ Great death pit

- ↑ "Iraq's Ancient Past: Rediscovering Ur's Royal Cemetery". Penn.museum. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- ↑ Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty - Free Media in Unfree Societies U.S. Archaeologists To Excavate In Iraq

- ↑ "Soldiers visit historical ruins of Ur", Nov 18, 2009, by 13th Sustainment Command Expeditionary Public Affairs, web: Army-595.

- ↑ "US returns Ur, birthplace of Abraham, to Iraq". AFP. 2009-05-14. Retrieved 2009-09-12.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-11-09. Retrieved 2010-11-09.

- ↑ DGCS

- ↑ online

- ↑ Franco D'Agostino et al, ABU TBEIRAH. PRELIMINARY REPORT OF THE FIRST CAMPAIGN (JANUARY-MARCH 2012), Rivista degli studi orientali Nuova Serie, vol. 84, Fasc. 1/4, pp. 17-34, 2011

- ↑ Franco D'Agostino et al, Abu Tbeirah. Preliminary report of the second campaign (October-December 2012), Rivista degli studi orientali, vol. 86(1), pp. 69-91, 2013

- ↑ Franco D'Agostino et al, Abu Theirah, Nasiriyah (Southern Iraq): Preliminary report on the 2013 excavation campaign, ISIMU 13, pp. 209-221, 2011

- ↑ Archaeologists Glance Into Fox Burrow in Iraq, Find 4,000-year-old Sumerian Port

References

- Crawford, Harriet. Ur: The City of the Moon God. London: Bloomsbury, 2015. ISBN 978-1-47252-419-5

- C.J. Gadd, History and monuments of Ur, Chatto & Windus, 1929 (Dutton 1980 reprint: ISBN 0-405-08545-1).

- P. R. S. Morrey, "Where Did They Bury the Kings of the IIIrd Dynasty of Ur?", Iraq, vol. 46, no. 1, pp. 1–18, 1984.

- P. R. S. Morrey What Do We Know About the People Buried in the Royal Cemetery?, Expedition Magazine, Penn Museum, vol. 20, iss. 1, pp. 24–40, 1977

- J. Oates, "Ur and Eridu: The Prehistory", Iraq, vol. 22, pp. 32–50, 1960.

- Pardo Mata, Pilar, "Ur, ciudad de los sumerios". Cuenca: Alderaban, 2006. ISBN 978-84-95414-38-0.

- Susan Pollock, Chronology of the Royal Cemetery of Ur, Iraq, vol. 47, pp. 129–158, British Institute for the Study of Iraq, 1985

- Susan Pollock, Of Priestesses, Princes and Poor Relations: The Dead in the Royal Cemetery of Ur, Cambridge Archaeological Journal, vol. 1, iss. 2, 1991

- Woolley, Leonard. Ur excavations IV: The Early Periods, Oxford University Press, 1927.

- Ur Excavations V: The Ziggurat and Its Surroundings, Oxford University Press, 1927.

- with M. E. L. Mallowan: Ur Excavations VII: The Old Babylonian Period, Oxford University Press, 1927

- Ur Excavations VIII: The Kassite Period, Oxford University Press, 1927

- with M. E. L. Mallowan: Ur Excavations IX: The Neo-Babylonian and Persian Periods, Oxford University Press, 1927

- Ur of the Chaldees: A record of seven years of excavation. Ernest Benn Limited, 1920.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ur. |

- An exploration of the Royal Tombs of Ur, with a comprehensive selection of high-resolution photographs detailing the treasures found in the tombs

- Explore some of the Royal Tombs, Mesopotamia website from the British Museum

- Treasures from the Royal Tombs of Ur

- British Museum and Penn Museum Ur site - has field reports

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Ur

- Woolley’s Ur Revisited, Richard L. Zettler, BAR 10:05, September/October 1984.

- Ur Excavations of the University of Pennsylvania Museum

- Explore Ur with Google Earth on Global Heritage Network

- At Ur, Ritual Deaths That Were Anything but Serene on The New York Times

- Ortho-photomap of Ur produced in 2014

- Web site for new Iraqi/Italian dig