Beetroot

| Beetroot | |

|---|---|

Beetroot | |

| Species | Beta vulgaris |

| Subspecies | Beta vulgaris subsp. vulgaris |

| Cultivar group | 'Conditiva' group |

| Origin | Sea beet (Beta vulgaris subsp. maritima) |

| Cultivar group members | Many; see text. |

The beetroot is the taproot portion of the beet plant,[1] usually known in North America as the beet, also table beet, garden beet, red beet, or golden beet. It is one of several of the cultivated varieties of Beta vulgaris grown for their edible taproots and their leaves (called beet greens). These varieties have been classified as B. vulgaris subsp. vulgaris Conditiva Group.[2]

Other than as a food, beets have use as a food colouring and as a medicinal plant. Many beet products are made from other Beta vulgaris varieties, particularly sugar beet.

Etymology

Beta is the ancient Latin name for beets,[3] possibly of Celtic origin, becoming bete in Old English around 1400.[4]

History

From the Middle Ages, beetroot was used as a treatment for a variety of conditions, especially illnesses relating to digestion and the blood. Bartolomeo Platina recommended taking beetroot with garlic to nullify the effects of "garlic-breath".[5]

During the middle of the 19th century, wine often was coloured with beetroot juice.[6]

Cultivars

Below is a list of several commonly available cultivars of beets. Generally, 55 to 65 days are needed from germination to harvest of the root. All cultivars can be harvested earlier for use as greens. Unless otherwise noted, the root colours are shades of red and dark red with different degrees of zoning noticeable in slices.

- 'Albino', heirloom (white root)

- 'Bull's Blood', heirloom[7]

- 'Chioggia', heirloom (distinct red and white zoned root)[8]

- 'Crosby's Egyptian', heirloom

- 'Cylindra' / 'Formanova', heirloom (elongated root)[8]

- 'Detroit Dark Red Medium Top', heirloom

- 'Early Wonder', heirloom

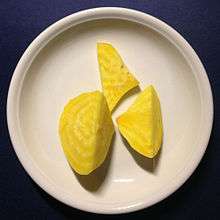

- 'Golden Beet' / 'Burpee's Golden', heirloom (yellow root)[8]

- 'Perfected Detroit', 1934 AAS winner[9]

- 'Red Ace' Hybrid

- 'Ruby Queen', 1957 AAS winner[10]

- 'Touchstone Gold' (yellow root)

Food

Usually the deep purple roots of beetroot are eaten boiled, roasted, or raw, and either alone or combined with any salad vegetable. A large proportion of the commercial production is processed into boiled and sterilized beets or into pickles. In Eastern Europe, beet soup, such as borscht, is a popular dish. In Indian cuisine, chopped, cooked, spiced beet is a common side dish. Yellow-coloured beetroots are grown on a very small scale for home consumption.[11]

The green, leafy portion of the beet is also edible. The young leaves can be added raw to salads, whilst the mature leaves are most commonly served boiled or steamed, in which case they have a taste and texture similar to spinach. Those greens selected should be from bulbs that are unmarked, instead of those with overly limp leaves or wrinkled skins, both of which are signs of dehydration.

The domestication of beets can be traced to the emergence of an allele which enables biennial harvesting of leaves and taproot.[12]

Beetroot can be boiled or steamed, peeled, and then eaten warm with or without butter as a delicacy; cooked, pickled, and then eaten cold as a condiment; or peeled, shredded raw, and then eaten as a salad. Pickled beets are a traditional food in many countries.

A traditional Pennsylvania Dutch dish is pickled beet egg. Hard-boiled eggs are refrigerated in the liquid left over from pickling beets and allowed to marinate until the eggs turn a deep pink-red colour.

In Poland and Ukraine, beet is combined with horseradish to form popular ćwikła, which is traditionally used with cold cuts and sandwiches, but often also added to a meal consisting of meat and potatoes. Similarly in Serbia where the popular cvekla is used as winter salad, seasoned with salt and vinegar, with meat dishes. As an addition to horseradish, it is also used to produce the "red" variety of chrain, a popular condiment in Ashkenazi Jewish, Hungarian, Polish, Lithuanian, Russian, and Ukrainian cuisine.

Popular in Australian hamburgers, a slice of pickled beetroot is combined with other condiments on a beef patty to make an Aussie burger.

In Northern Germany, beetroot is mashed with Labskaus or added as its side order. [13][14]

When beet juice is used, it is most stable in foods with a low water content, such as frozen novelties and fruit fillings.[15] Betanins, obtained from the roots, are used industrially as red food colourants, e.g. to intensify the colour of tomato paste, sauces, desserts, jams and jellies, ice cream, sweets, and breakfast cereals.[11]

Beetroot can also be used to make wine.[16]

A moderate amount of chopped beetroot is sometimes added to the Japanese pickle fukujinzuke for color.

Food shortages in Europe following World War I caused great hardships, including cases of mangelwurzel disease, as relief workers called it. It was symptomatic of eating only beets.[17]

Nutrition

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 180 kJ (43 kcal) |

|

9.56 g | |

| Sugars | 6.76 g |

| Dietary fiber | 2.8 g |

|

0.17 g | |

|

1.61 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin A equiv. |

0% 2 μg0% 20 μg |

| Thiamine (B1) |

3% 0.031 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) |

3% 0.04 mg |

| Niacin (B3) |

2% 0.334 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) |

3% 0.155 mg |

| Vitamin B6 |

5% 0.067 mg |

| Folate (B9) |

27% 109 μg |

| Vitamin C |

6% 4.9 mg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium |

2% 16 mg |

| Iron |

6% 0.8 mg |

| Magnesium |

6% 23 mg |

| Manganese |

16% 0.329 mg |

| Phosphorus |

6% 40 mg |

| Potassium |

7% 325 mg |

| Sodium |

5% 78 mg |

| Zinc |

4% 0.35 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 87.58g |

|

| |

| |

|

†Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient Database | |

Raw beetroot is 88% water, 10% carbohydrates, 2% protein, and less than 1% fat (see table). In a 100-gram amount providing 43 calories, raw beetroot is a rich source (27% of the Daily Value - DV) of folate and a moderate source (16% DV) of manganese, with other nutrients having insignificant content (table).[18]

Preliminary research

In preliminary research, beetroot juice reduced blood pressure in hypertensive animals,[19] so may have an effect on mechanisms of cardiovascular disease.[20][21] Tentative evidence has found that dietary nitrate supplementation such as from beets and other vegetables results in a small to moderate improvement in endurance exercise performance.[22]

Beets contain betaines, which may function to reduce the concentration of homocysteine,[23] a homolog of the naturally occurring amino acid cysteine. High circulating levels of homocysteine may be harmful to blood vessels, thus contribute to the development of cardiovascular disease.[24] As of 2008 this hypothesis is controversial as it has not yet been established whether homocysteine itself is harmful or is just an indicator of increased risk for cardiovascular disease.[24][25]

Other uses

Betanin, obtained from the roots, is used industrially as red food colorant, to improve the color and flavor of tomato paste, sauces, desserts, jams and jellies, ice cream, candy, and breakfast cereals, among other applications.[11]

The chemical adipic acid rarely occurs in nature, but happens to occur naturally in beetroot.

Safety

The red colour compound betanin is not broken down in the body, and in higher concentrations may temporarily cause urine or stools to assume a reddish colour, in the case of urine a condition called beeturia.[26] Although harmless, this effect may cause initial concern due to the visual similarity to what appears to be blood in the stool, hematochezia (blood passing through the anus, usually in or with stool) or hematuria (blood in the urine).[27]

Nitrosamine formation in beet juice can reliably be prevented by adding ascorbic acid.[28]

See also

References

- ↑ "beet". def. 1 and 2. also "beet-root". Oxford English Dictionary Second Edition on CD-ROM (v. 4.0) © Oxford University Press 2009

- ↑ "Sorting Beta names". Multilingual Multiscript Plant Name Database. The University of Melbourne. Archived from the original on 2013-04-15. Retrieved 2013-04-15.

- ↑ Gledhill, David (2008). "The Names of Plants". Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521866453 (hardback), ISBN 9780521685535 (paperback). pp 70

- ↑ "Beet". Online Etymology Dictionary, Douglas Harper. 2017. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- ↑ Platina De honesta voluptate et valetudine, 3.14

- ↑ Nilsson et al. (1970). "Studies into the pigments in beetroot (Beta vulgaris L. ssp. vulgaris var. rubra L.)"

- ↑ "Baby Bulls Blood Beets Information". Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- 1 2 3 Stebbings, Geoff (2010). Growing Your Own Fruit and Veg For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781119992233. Retrieved 31 July 2018 – via Google Books.

- ↑ "AAS Beet Perfected Detroit". Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ↑ "AAS Beet Ruby Queen". Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- 1 2 3 Grubben, G.J.H. & Denton, O.A. (2004) Plant Resources of Tropical Africa 2. Vegetables. PROTA Foundation, Wageningen; Backhuys, Leiden; CTA, Wageningen.

- ↑ Pin, Pierre A.; Zhang, Wenying; Vogt, Sebastian H.; Dally, Nadine; Büttner, Bianca; Schulze-Buxloh, Gretel; Jelly, Noémie S.; Chia, Tansy Y. P.; Mutasa-Göttgens, Effie S. (2012-06-19). "The Role of a Pseudo-Response Regulator Gene in Life Cycle Adaptation and Domestication of Beet". Current Biology. 22 (12): 1095–1101. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2012.04.007. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 22608508.

- ↑ SPIEGEL Online on Labskaus in Hamburg (German), Der Spiegel

- ↑ Labskaus mit Rote-Bete-Salat (German), recipe at NDR

- ↑ Francis, F.J. (1999). Colorants. Egan Press. ISBN 1-891127-00-4.

- ↑ Making Wild Wines & Meads; Pattie Vargas & Rich Gulling; page 73

- ↑ MacMillan, Margaret Olwen (2002) [2001]. "We are the League of the People". Paris 1919: Six Months That Changed the World (1st U.S. ed.). New York: Random House. p. 60. ISBN 0375508260. LCCN 2002023707.

Relief workers invented names for things they had never seen before, such as the mangelwurzel disease, which afflicted those who lived solely on beets.

- ↑ "Nutrient data for beets, raw per 100 g". United States Department of Agriculture, National Nutrient Database, release SR-28. 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- ↑ Lundberg, J.O.; Carlström, M.; Larsen, F.J.; Weitzberg, E. (2011). "Roles of dietary inorganic nitrate in cardiovascular health and disease". Cardiovasc Res. 89 (3): 525–32. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvq325. PMID 20937740.

- ↑ Hobbs, D. A.; Kaffa, N.; George, T. W.; Methven, L.; Lovegrove, J. A. (2012). "Blood pressure-lowering effects of beetroot juice and novel beetroot-enriched bread products in normotensive male subjects". British Journal of Nutrition. 108 (11): 2066–2074. doi:10.1017/S0007114512000190. PMID 22414688.

- ↑ Siervo, M.; Lara, J.; Ogbonmwan, I.; Mathers, J. C. (2013). "Inorganic Nitrate and Beetroot Juice Supplementation Reduces Blood Pressure in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Journal of Nutrition. 143 (6): 818–826. doi:10.3945/jn.112.170233. PMID 23596162.

- ↑ McMahon, Nicholas F.; Leveritt, Michael D.; Pavey, Toby G. (6 September 2016). "The Effect of Dietary Nitrate Supplementation on Endurance Exercise Performance in Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Sports Medicine. doi:10.1007/s40279-016-0617-7. PMID 27600147.

dietary NO3− supplementation such as nitrate-rich vegetable sources or beetroot juice

- ↑ Pajares, M. A.; Pérez-Sala, D (2006). "Betaine homocysteine S-methyltransferase: Just a regulator of homocysteine metabolism?". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 63 (23): 2792–803. doi:10.1007/s00018-006-6249-6. PMID 17086380.

- 1 2 A.D.A.M., Inc., ed. (2002). Betaine. University of Maryland Medical Center.

- ↑ Potter, K.; Hankey, G. J.; Green, D. J.; Eikelboom, J. W.; Arnolda, L. F. (2008). "Homocysteine or Renal Impairment: Which is the Real Cardiovascular Risk Factor?". Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 28 (6): 1158. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.162743.

- ↑ Frank, T; Stintzing, F. C.; Carle, R; Bitsch, I; Quaas, D; Strass, G; Bitsch, R; Netzel, M (2005). "Urinary pharmacokinetics of betalains following consumption of red beet juice in healthy humans". Pharmacological Research. 52 (4): 290–7. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2005.04.005. PMID 15964200.

- ↑ "Urine color". Mayo Clinic, Patient Care and Health Information, Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ↑ Kolb E, Haug M, Janzowski C, Vetter A, Eisenbrand G (1997). "Potential nitrosamine formation and its prevention during biological denitrification of red beet juice". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 35 (2): 219–24. doi:10.1016/s0278-6915(96)00099-3. PMID 9146735. Retrieved 2015-06-06.

External links

![]()

.jpg)

.jpg)