Tarichaea

| el-Malaḥa | |

|

| |

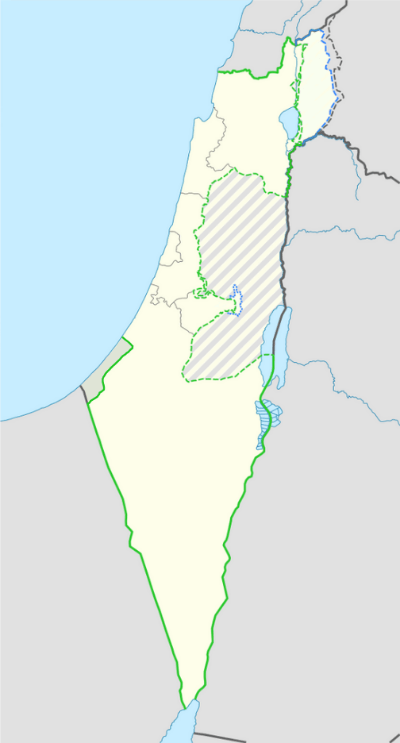

Shown within Mandatory Palestine  Tarichaea (Israel) | |

| Alternative name | Taricheæ, Tarichaeae |

|---|---|

| Location |

|

| Region | Lower Galilee |

| Coordinates | 32°43′05″N 35°34′19″E / 32.717958°N 35.571864°E |

| History | |

| Periods | Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine |

| Site notes | |

| Archaeologists | Nikos Kokkinos |

Tarichaea (Greek: Ταριχαία or Ταριχέα), alternative spellings, Tarichese; Tarichess; Tarichee, (Heb: מלחה), is the Greek place name for a historic site, formerly situated along the shore of the Sea of Galilee, and mentioned in the writings of Josephus (Ant. 14.20; 20. 159; J.W. 1. 180; 2. 252; Vita 32, et al.). Tarichaea was one of the first villages in Galilee to have sustained an attack by Rome, during the First Jewish-Roman War. The village (κώμη)[1] attracted to it the seditious from the outlying regions east of Galilee,[2] who mixed with the local townsfolk and who relied upon some 230 boats on the Sea of Galilee for protection in the event of an assault upon the village. When the village was eventually overran by the Roman army, the townsfolk surrendered.[3]

History

In ca. 52 BCE, Judea was invaded by the Roman governor of Syria, Gaius Cassius Longinus, who fell upon the town of Tarichæa and carried away thirty thousand Jews into slavery.[4] Roughly, one-hundred years later, in the first year of Emperor Nero's reign, a stupendous gift was added to Agrippa II's realm, when Nero entrusted him with the government of a certain part of Galilee, Tiberias and Tarichæa.[5] In the 12th-year of Nero's reign, when war broke out between Rome and the Jews of Judea, Josephus was appointed the governor of the Galilee, and took care to build the wall of Tarichæa, as well as of other towns in Galilee, in anticipation of a Roman assault against these cities.[6]

At that time, Josephus chose Tarichæa for his place of residence. When certain young men of the village Dabarittha had robbed the king's steward of six-hundred pieces of gold, no small number of silver vessels and of many costly garments, at a time when he passed through their region of the country, Josephus retrieved the money and items when they came to him at Tarichæa, secretly hoping to return such items to the king, and withal blamed them for the violence they had offered the king. However, thinking that Josephus was not of like mind with them and that he secretly entertained notions of betraying them to the king who was allied with the Romans, they raised a commotion in all the neighboring cities, saying that Josephus had designs of betraying the people to the Romans. At this accusation, some one-hundred thousand armed men came to him at Tarichæa, which multitude was crowded together in the town's hippodrome (a place that should rather be considered as a race course devoid of monumental construction), and they raised a clamor against Josephus.[7] Josephus' repartee and skill at oration was able to save himself from imminent danger, by suggesting that he had retrieved the money, not to return to the king, but to finish building the wall of Tarichæa. The indigenous people of Tarichæa, numbering then forty thousand, rose up to his defense and prevented his bloodshed.[8] When the people of Tiberias eventually revolted against Josephus, Josephus devised methods to detain many of the city's governors and principal persons (among whom was Justus of Tiberias), having them transported by boats to Tarichæa where they were incarcerated.[9]

With the exception of Jesus ben Shafat and his party who escaped from Tiberias and joined the seditious in Tarichæa, the people of Tiberias received the Roman army into their city and made peace with the Romans.[10]

Outcome of war

Josephus, in his extensive accounts of the military history of Tarichæa, relates that Vespasian, the acting Roman general in ca. 64 CE, and his son, Titus, having received intelligence that the inhabitants of Tarichæa had revolted against the Romans, were resolved to punish them. According to Josephus, Vespasian and his son, Titus, encamped with three legions at a place called Sennabris[11] (Σενναβρìs - סנבראי), south of Tiberias and "easily seen by the innovators"[12] (where is now located Moshavat-Kinneret), in preparation for the war with Tarichæa. Like Tarichæa, it too was situated some 30 stadia (ca. 5.5 kilometres (3.4 mi)) from Tiberias.[13][14] Vespasian sent against the town four-hundred horsemen and two thousand archers, under Antonius and Silo, to repel those that were upon the wall. Josephus informs his readers that "after the battle, Vespasian held a court-martial in Tarichaea. Making a distinction between the residents and the newcomers whom he considered responsible for the war, he put the question to his staff whether these too should be spared. The verdict was that it would be against the public interest to set them free."[15] By way of a contrivance, Vespasian permitted the residents to take leave only by the road that led to Tiberias, and when they had gone a certain distance, without suspecting anything, the Roman soldiers conducted them into the Stadium that was built in Tiberias. Of these, the aged and useless, numbering some 1,200, were slain by the soldiers at Vespasian's orders. Of the young men, he picked out 6,000 of the strongest and sent them to Nero at the Isthmus, to help in digging the Corinth Canal. The rest of the people, to the number of 30,400, he sold at auction, excepting only those whom he presented to Agrippa and who had come from his own kingdom.[16]

Before the fall of the city, Josephus escaped and continued the prosecution of the war in Jotapata (Hebrew: יודפת), until he was captured there.[17]

Geographical location

The location of Tarichæa has been the subject of intensive debate. Josephus frequently refers to a wealthy Galilean town, destroyed by the Romans in the Jewish War (66-73 CE)[18] that has the Greek name "Tarichæa" from its prosperous fisheries. Josephus does not give its Hebrew name. Some authors[19][20][21] identify this with Magdala Nunaiya - which refers to its "fish tower" for processing (drying) fish. It was also known in biblical times for flax weaving and dyeing.[19] It was a major campaign camp/fortress of Josephus during the Jewish Wars.[18] The one problem, however, with this identification is that Josephus places Tarichæa some thirty stadia (furlongs) from Tiberias, or what are a little more than 5.5 kilometres (3.4 mi),[22] which would be further in distance than Magdala is to Tiberias. Moreover, during the Roman attempt to quell the insurrection at Tarichaea, Vespasian and his son, Titus, encamped with three legions at a place called Sennabris[23] (Σενναβρìs - סנבראי), south of Tiberias and "easily seen by the innovators."[24] The German traveler, Ulrich Jasper Seetzen, described Tarichæa in 1806 as being on the banks of the Sea of Galilee at its "southward extremity," saying that, in his day, some ruins and some walls were still visible, and that the place still bore the name of el-Malahha, or Ard-el-Malahha, which is synonymous with the Greek name of Tarichæa,[25] a name derived from the Greek word tarichos - salting fish.[26] Seetzen surmises that the inhabitants of Tarichæa made use of ground salt that was plenteous in their town to cure the quantities of fish produced by the lake. Pliny, likewise, places Tarichæa to the south of the Sea of Galilee.[27] Accordingly, C.R. Conder, identified Tarichaea with Kerek, a place situated to the south of Tiberias.[28] In contrast, H.H. Kitchener of the Palestine Exploration Fund suggested that Tarichæa is to be identified with the ruin, Khurbet Kuneitriah, between Tiberias and Migdal, 2.5 kilometres (1.6 mi) northwest of Tiberias.[29] W.F. Albright, however, thought that Mejdel (Magdala) - to the north of Tiberias - was to be identified with Tarichæa,[30][31] an opinion followed by Avi-Yonah.[32]

Josephus places Tarichæa along the shores of Lake of Gennesaret, directly opposite Gamala which lay on the opposite side of the lake.[33] Josephus adds that while Gamala belonged to the Lower Gaulonitis, Tarichæa belonged to Lower Galilee.[34]

References

- ↑ Josephus, in Wars 4:455, gives to the town the designation of "village" (κώμη), which perhaps should not be taken literally, based on the number of its inhabitants.

- ↑ Josephus informs his readers that these came from Trachonitis, Gaulonitis, Hippos and the Gadarene district (Josephus, The Jewish War, IV, 7, New York 1980, p. 223).

- ↑ Josephus, The Jewish War, IV, 7, New York 1980, p. 223

- ↑ Josephus, De Bello Judaico (Wars of the Jews), book i, chapter viii, § 9

- ↑ Josephus, Antiquities, book xx, chapter viii, § 4; De Bello Judaico (Wars of the Jews), book ii, chapter xiii, § 2

- ↑ Josephus, De Bello Judaico (Wars of the Jews), book ii, chapter xx, § 6

- ↑ Josephus, De Bello Judaico (Wars of the Jews), book ii, chapter xxi, § 3

- ↑ Josephus, De Bello Judaico (Wars of the Jews), book ii, chapter xxi, § 4

- ↑ Josephus, De Bello Judaico (Wars of the Jews), book ii, chapter xxi, § 9

- ↑ Josephus, De Bello Judaico (Wars of the Jews), book iii, chapter xxi, § 9

- ↑ The place is described by H.H. Kitchener, in the April 1878 Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly Statement, Survey of Galilee, p. 165, "During the survey of the shores [of the Sea of Galilee] we made one considerable discovery: the site of Sennabris, mentioned by Josephus as the place where Vespasian pitched his camp when marching on the insurgents of Tiberias. The name Sinn en Nabra still exists, and is well known to the natives; it applies to a ruin situated on a spur from the hills that close the southern end of the Sea of Galilee; it formed, therefore, the defence against an invader from the Jordan plain, and blocked the great main road in the valley. Close beside it there is a large artificially-formed plateau, defended by a water-ditch on the south, communicating with Jordan, and by the Sea of Galilee on the north. This is called Kh. el Kerak, and is, I have not the slightest doubt, the remains of Vespasian's camp described by Josephus."

- ↑ Josephus, Wars of the Jews (book iii, chapter ix, § 7)

- ↑ Josephus, Wars of the Jews (3:447)

- ↑ Josephus, Flavius; Mason, Steve (2003). Life of Josephus (Reprint, illustrated ed.). Brill, p. 193. ISBN 978-0-391-04205-6.

- ↑ Josephus, The Jewish War, IV, 7, New York 1980, p. 222

- ↑ Josephus, De Bello Judaico (Wars of the Jews), book iii, chapter x, § 10

- ↑ Josephus, Vita § 74

- 1 2 Flavius, Josephus; Thackeray, H. StJ. [translator] (1989). The Jewish War (Loeb Classical Library ed.). Cambridge Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0 674 99223 7.

- 1 2 Gardner, Laurence (2005). The Magdalene legacy. London: Element (Harper Collins). ISBN 0 00 720186 9.

- ↑ Achtermeier, P. J. (Ed.) (1996). The Harper Collins Bible Dictionary. San Francisco: Harper Collins.

- ↑ Andrea Garza-Díaz, The Archaeological Excavations at Magdala, Ancient History Encyclopedia, 19 April 2018

- ↑ Josephus, Vita § 32

- ↑ The place is described by H.H. Kitchener, in the April 1878 Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly Statement, Survey of Galilee, p. 165, "During the survey of the shores [of the Sea of Galilee] we made one considerable discovery: the site of Sennabris, mentioned by Josephus as the place where Vespasian pitched his camp when marching on the insurgents of Tiberias. The name Sinn en Nabra still exists, and is well known to the natives; it applies to a ruin situated on a spur from the hills that close the southern end of the Sea of Galilee; it formed, therefore, the defence against an invader from the Jordan plain, and blocked the great main road in the valley. Close beside it there is a large artificially-formed plateau, defended by a water-ditch on the south, communicating with Jordan, and by the Sea of Galilee on the north. This is called Kh. el Kerak, and is, I have not the slightest doubt, the remains of Vespasian's camp described by Josephus."

- ↑ Josephus, Wars of the Jews (book iii, chapter ix, § 7)

- ↑ Ulrich Jasper Seetzen, Brief Account of the Countries adjoining the Lake of Tiberias, Palestine Association of London: London 1810, pp. 21–22, notes page 2

- ↑ See p. 140 in: Vilnay, Zev (1954). "Identification of Talmudic Place Names". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 45 (2): 130–140. JSTOR 1452901.

- ↑ Pliny wrote in his Hist. Nat. v. 71: "On the east Julias and Hippos, on the south Tarichaea (“a meridie Tarichea”), by which name the lake also was formerly called, on the west Tiberias" (Rel. Pal. p. 440), cited in Quarterly Palestine Exploration Fund, p. 181.

- ↑ Kerek

- ↑ H.H. Kitchener, Survey of Galilee, Palestine Exploration Fund, London 1878, pp. 165–166.

- ↑ See p. 13 in: Albright, W.F. (1923). "Some Archaeological and Topographical Results of a Trip through Palestine". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 11: 3–14. JSTOR 1354763.

- ↑ The Location of Tarichaea: North or South of Tiberias?, Abstract from Nikos Kokkinos, Palestine Exploration Quarterly (Volume: 142, Issue: 1), 2010, pp. 7-23.

- ↑ Michael Avi-Yonah, Map of Roman Palestine (Second revised edition), London 1940, p. 37

- ↑ Josephus, The Jewish War, IV, 7, New York 1980, p. 223; Josephus, De Bello Judaico (Wars of the Jews), book iv, chapter i, § 1

- ↑ Josephus, Vita § 37

External links

- The location of Tarichaea: north or south of Tiberias?

- *

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |