Battle of Pontvallain

| Battle of Pontvallain | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Hundred Years' War | |||||||

Battle of Pontvallain (and Anointing of Pope Gregory XI on the left) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 5,200[1][1] | 4,000–6,000 men[2][3] | ||||||

The Battle of Pontvallain was fought on 4 December 1370 in the Sarthe region during the Hundred Years' War. English forces that had broken away from the army commanded by Sir Robert Knolles fought a French army under the newly appointed Constable of France, Bertrand du Guesclin.

The battle was in fact two separate engagements: one at Pontvallain and a smaller one at the nearby town of Vaas. The two are sometimes named as separate battles. Though the engagements were comparatively small-scale, they were significant because the English were routed, thus ending a reputation for invincibility in open battle that they had enjoyed since the wars started in 1337.

Background

| “ | In 1340 Edward III officially laid claim to the French throne and thereby transformed his struggle with Philip VI, the Valois king of France, from a feudal squabble between liege lord and vassal into a war between two contenders for the royal succession.[4] | ” |

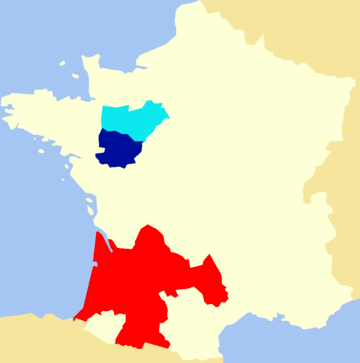

The Hundred Years' War had begun in earnest in 1340, when the English King Edward III claimed the French crown, believing himself the rightful heir. This was because, through his mother, Isabella of France, he was the blood heir of the previous King, Charles IV. However, the French nobility refused to recognise Edward's claim, because the salic law—which governed French royal succession—prohibited inheritance through the female line.[5][note 1] The French nobility preferred Philip of Valois, and in 1336, Philip attempted to confiscate the Duchy of Aquitaine. Whilst in France, this had been the patrimony of English kings ever since Eleanor of Aquitaine had brought it as dowry to King Henry II.[9][10] Edward formally proclaimed himself King of France in 1340, and the following year involved himself in the War of the Breton Succession—against the interests of the French King—and in 1346 they fought their first battle. This was at Crécy,[11] and it was the first in a long run of military successes enjoyed by the English that was only to be stopped by the Black Death in 1348.[12][13][note 2] The war recommenced in 1355, and when the following year the Prince of Wales won another decisive victory at the Battle of Poitiers, in which King John II of France was captured.[16]

A French offensive to recapture castles in Normandy in August 1369 had restarted the war,[17] and it went poorly for England almost from the start. James Audley and John Chandos, two important commanders for the English, were killed in the first six months[18] while the French made territorial gains, re-occupying Poitou and regaining many castles.[19] Men who had fought in earlier English campaigns were summoned from their retirements,[19][note 3] and new men such as the Earl of Pembroke were given commands.[21]

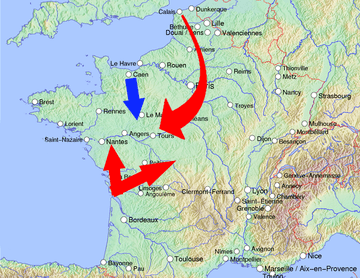

Sir Robert Knolles landed at Calais in August 1370 with an army of between 4,000[2] to 6,000 mounted men.[3] There he awaited further orders from the King. None, however, were forthcoming, so he proceeded on[3] a ("meandering")[2] campaign in the style of a plundering raid through northern France. According to T. F. Tout, du Guesclin allowed Knolles and his army "to wander where he would."[3][note 4] Knolles crossed north-eastern France in what by now was a traditional English tactic, the chevauchée. This was intended not only to inflict as much destruction as possible on the countryside they passed through, but by doing so, draw out the French army into a pitched battle.[23] Journeying through the Somme region, Knolles made a show of force outside Reims, down to Troyes, and then swung west in order to approach Paris from the direction of Nemours. As they marched, Knolles' army captured many towns, which they would then destroy if the French refused to pay the ransoms that the English demanded of them.[24][note 5] He reached Paris on 24 September; but the city was well garrisoned and well defended. Knolles could not enter, and the French defenders would not leave their positions. He tried to draw them out and engage them in a pitched battle, but the French would not take the bait.[24][note 6]

By October Knolles had moved south and was marching towards Vendôme.[26] He captured and garrisoned castles and monasteries between the rivers Loir and Loire and positioned himself to be able to march into Poitou or alternatively into southern Normandy if his King, Edward III, concluded an agreement with Charles II of Navarre, who was offering his lands in northern Normandy as a base for the English. Many of the subordinate captains, who considered themselves better-born than Knolles, deplored his apparent lack of martial spirit. They found a leader in Sir John Minsterworth, an ambitious but unstable knight from the Welsh Marches who mocked Knolles as "the old freebooter".[27]

Much of Knolles' strategy was based on that employed in the campaigns of the 1340s and 1350s, particularly the capturing of enemy fortresses, in order to either garrison them with English troops or levy a ransom.[28][note 7]

The English campaign in the west, on the other hand, which was commanded by Edward the Black Prince, John Chandos and John Hastings, Earl of Pembroke, began achieving some successes, successfully capturing Limoges after a five-day siege, and capturing many ransoms and much booty.[30][note 8]

Tactics and strategy

The second phase of the Hundred Years' War, starting in 1369, was significantly different from the previous phase in many aspects. The French were well prepared for battle, and went straight away on the offensive.[23] Charles V was in a vastly improved situation in terms of financial and human resources,[33] and also benefited from technological improvements in barding for instance, which had been dramatically improved and went on to play an important role at Pontvallain where English arrows did little damage to French cavalry.[34] The area of fighting in this phase took place almost solely in Aquitaine, which meant the English had extremely long, intricate borders to defend. They were, however, easy for small French forces to penetrate, in which the French did "with excellent effect" relying on Fabian tactics.[23] This involved avoiding pitched battles and using attrition to wear down the English,[33] occasionally attacking dispersed and isolated English forces, as the French would do at Pontavallain.[35] This was now a defensive war for the French, and the English were ill-prepared for it.[23] One of the most important of aspects of the French campaign, it has been suggested, was the speed with which it was carried through: du Guesclin and his forces left Caen on 1 December, and arrived at Le Mans two days later, a journey of over 100 miles.[36]

Commanders and leaders

England

Although Aquitaine and Poitou were fiefdoms of Edward the Black Prince, by 1370 he was so ill that he had to be transported in a litter.[19] As a result, he was unable to lead the campaign personally and needed seasoned captains—such as Knolles—to campaign for him. Although Knolles had indentured on 20 June 1370 to lead the King's army, he had already (a week earlier) agreed to share the command with Sir Alan Buxhill, Sir Thomas Grandison and Sir John Bourchier. On 1 July they were all jointly appointed King's lieutenants. However, it seems that either the King, or his council, were aware of the problems that could be caused by giving the overall command to Knolles, whose social status was lower than his peers. To prevent the English army from dividing and going separate ways—and in what Jonathan Sumption has called "a prescient precaution"[37]— the captains were required to sign an agreement before they left agreeing not only to serve the King faithfully, but also not to allow any divisions to open up between them, and to made decisions collectively.[37]

France

Meanwhile, Charles V of France had invested a knight, Bertrand du Guesclin, with the office of constable of France, in direct response to Knolles's campaign.[38] On the 24th of that month, du Guesclin sealed a "pact of brotherhood-in-arms" with Olivier de Clisson, and by 6 November du Guesclin was in Caen raising an army.[36]

Du Guesclin had been a prisoner of the English and Charles ransomed du Guesclin in order to immediately employ him.[33] Charles appointed him Constable of France, and tasked du Guesclin with the mission of destroying Knolles’ army. In November du Guesclin concentrated his forces at Caen where he was joined by reinforcements under the Marshals Mouton de Blainville and Arnoul d'Audrehem as well as a Breton contingent under de Clisson. Du Guesclin was thus able to raise about 4,000 men. A second army of about 1,200 men was formed in Knolles’s rear at Châtellerault under Marshal Sancerre, which then moved towards Knolles from the East while Du Guesclin began to move on him from the north.[1]

Divisions among the English leadership

The system of shared leadership led to jealousies within the captains of the English force, particularly regarding how the many ransoms and booty they had collected would be distributed.[39][note 9]

The Anonimalle Chronicle, 64-5.

In November 1370 acrimony again broke out amongst the English captains, this time on the issue of where to spend the winter with their armies. Knolles, as adept as the French were now becoming at guerrilla warfare, was aware that the French were closing in. Not wishing to stay encamped in an area where a surprise attack was possible, he proposed withdrawing westward into Brittany. His captains, though, led by Sir Alan Buxhill, violently disagreed, preferring to find winter quarters where they were and to continue to raid the surrounding countryside, confident they could defeat any French attack.[42] Their concern to keep pillaging the countryside was not necessarily something they had much choice in: the government had only paid theirs and their army's wages for thirteen weeks, and they were clearly expected to not just live off the land, but pay themselves from it too.[24][note 10] Knolles threatened to leave, and when they refused to join him, did so, and took the largest retinue from the army with him[42]—"doubtless with considerable booty," remarked Kenneth Fowler.[46] In Knolles' absence, what remained of the English force of approximately 4,000 men[38] was divided into three sections. One was under the dual command of Grandison and Calveley, the other two by Fitzwalter and Minsterworth.[47] They in turn went separate ways in order to maximise their foraging,[42] Minsterworth probably being the first to leave.[38] On the evening of 3 December, Knolles was way to the west, Grandison's force of between 600 and 1,200 was spread out along a river between Pontvallain and Mayet, and Fitzwalter was some miles to the south. Minsterworth's battalions were at a now unknown location.[42] The decision to split their forces into discrete portions was to prove a fatal one.[38]

|

Battle of Pontvallain

It was, therefore, what remained of the English army under Lord Fitzwalter in Maine[48] that du Guesclin encountered first. His rear-guard bore the brunt of the French assault, whilst encamped near Le Mans,[49] On 1 December du Guesclin left Caen with his army ("One of those marches of which he had the secret," said a contemporary chronicler),[50] and marched south, "covering more than thirty miles a day." He stopped on approaching Le Mans two days later.[51] There he received intelligence that Grandison's force was now at nearby Mayet, but was on the move to attempt to join with Knolles. Du Guesclin, however, outmanoeuvred him.[36] Despite his army being near- exhausted, du Guesclin commenced a night march, which brought his army to Pontvallain by early morning, 4 December. The fact that the French were able to attack Grandison's army with no warning was a great psychological advantage to them, and Grandison may have only had time to form rough lines with his men before fierce close-quarters fighting began.[51] The English, taken completely by surprise, attempted an escape through the woods[36] but were unable to retreat northwards, where the slightly higher ground could have provided them with a breathing space. Soon, with heavy losses on both sides, Grandison's force was crushed beneath the walls of the Château de la Faigne.[51]

The only – but most – significant French casualty of the battle was the Marshal, Arnoul d'Audrehem, who was mortally wounded. The English army, however, died almost to a man, with Grandison and his captains being among the few survivors. They were taken prisoner by du Guesclin.[52] Also captured were Philip Courtenay and Hugh Despencer.[36] With Grandison's defeat the mantle of being the largest English force in the area was passed to Fitzwalter. Sancerre – who was still "a few hours march away" – turned south to confront Fitzwalter on hearing of the battle at Pontvallain. Du Guesclin, meanwhile, organised his prisoners, sent a portion of his army to chase Knolles, and immediately moved in towards Fitzwalter from the east. The latter managed to avoid being surprised in open ground like Grandison had been, and raced south, intending to take refuge within the fortified walls of Vaas Abbey.[52]

Battle of Vaas

The Abbey at Vaas was garrisoned by Knolles's men, in which Fitzwalter's men assumed to be a safe haven. However, The French forces led by Sancerre reached the Abbey nearly the same time as the English did; the latter having had no time to organise a set piece defence of the Abbey, and they had to attempt to fend off an immediate assault from Sancerre. It seems likely that Fitzwalter's force had managed to enter the outer gate, and, after bitter fighting, Sancerrre also managed to force his way in. Fitzwater's defence, such as it was, became a massacre. The arrival of du Guesclin effectively put an end to the battle, which became a rout. What Jonathan Sumption considers "reliable estimates" attest the English losses to number over 300; this figure is exclusive of prisoners.[51] They included Fitzwalter himself (captured by the seneschal of Toulouse), and most of his lieutenants. Du Guesclin held Fitzwalter as his personal prisoner: possibly, Sumption adds, like d'Orgemont in his chronicle when later relating the tale, du Guesclin believed Fitzwalter to be the Marshal of England.[51]

Aftermath

The few survivors of both battles "scattered in confusion." John Minsterworth's battalions, which had not been engaged at either battle, immediately removed itself into Brittany. Others made their way to Saint-Saveur. Caveley returned to Poitou. Around 300 of the English remnants joined together and overran Courcillon Castle, near Château-du-Loir, and thence to the Loire, all the time closely pursued by Sancerre.[53] Many of Knolles's men abandoned their positions holding various castles, including Rillé and Beaufort la Vallée and also headed to the Loire.[53] This group, composed primarily of wounded men and pillagers, joined up with the other English group heading to the Loire,[54] which made them "several hundred" in strength, and continued heading south. However, du Guesclin maintained his close pursuit, and his constant ambushes and attacks depleted English numbers further. They eventually reached the relative safe haven of the ford at Saint-Maur, beyond which was a strong English garrison at the Abbey. Here, some went east, whilst the majority continued towards Bordeaux. This group was pursued by du Guesclin– now with Sancerre again – deep into Poitou, where it was eventually run to ground outside Bressuire Castle. This was also occupied by an English garrison, but, fearing they would admit the French army, alongside the English, if they opened the gates, they failed to do so.[53] As a result, what remained of the Pontvallain army died outside the walls.[54]

Sancerre proceeded to regain the castles previous held by Knolles after his chevauchée, as La Ferté-Beauharnais, which still needed to be taken by force. Likewise, du Guesclin made his way back to Saint-Maur where he negotiated with the English inside the Abbey– led by Sir John Cresswell – and arranged their release on payment of a ransom. The price of English freedom remains unknown, but, soon after, du Guesclin returned to Le mans and dwelt in the house of Louis of Anjou.[55]

There is uncertainty as to exactly where in Brittany Knolles retired to[56] with the "considerable booty" he must by now have garnered.[46] Whether to Derval or Concarneau– one and then to the other[46]– He was soon joined by Minsterworth, who, with most of his force decided to return to England early the following year. They made their way to the port of Pointe Saint-Mathieu, although continuous ambushes depleted their numbers before getting there. Worse, when they arrived, there were only two small ships available, yet a couple of hundred with Knolles and Minsterworth.[57] Their numbers were swollen by many English soldiers from the various garrisons that had evacuated and independently made their way to the port.[46] Minsterworth was one of the relative few who could buy a passage; most of those who remained were massacred by the French, who soon caught up with them,[57] possibly amounting to around 500 men.[46]

The return of Minsterworth to England "began a long period of recrimination," politically.[25] Although he was as culpable as Knolles or any of the other commanders, Minsterworth managed to avoid almost all the blame for the military disaster that had befallen them by putting responsibility on to Knolles.[58] In July 1372, the King's Council effectively agreed with him, and condemned Knolles for the defeat,[58][59] while the English nobility blamed Knolles entirely because of his lower social status.[59] Despite this, Minsterworth was unable to exculpate himself completely, and the Council had him arrested and charged with traducing Knolles.[60]

Sumption notes that "there can be no gainsaying du Guesclin's achievement," even if he had failed to confront or destroy the bulk of the English army still with Knolles and Minsterworth.[55] Many knights were captured by the French, including John Clanvowe, Edmund Daumarle and William Neville,[61] and were conveyed all the way to Paris in the back of open carts and strictly imprisoned.[55] Others spent great sums evading capture– and even borrowing money from colleagues to do so.[62] Fitzwalter was held prisoner until he was able to raise a ransom by mortgaging his Cumberland estates on ruinous terms to Edward III's mistress Alice Perrers.[63]

Legacy

Knolles' campaign has been estimated to have cost Edward III somewhere in the region of £66,667 (equivalent to £30,762,245 in 2016), based on his known requests for loans.[64][note 11] But the chevauchée that preceded the battle yielded, it has been said, "plunder but little military benefit,"[68] while Maurice Keen noted that even though Knolles had reached the gates of Paris, "he had little to show for it when he reached Brittany."[69] and illustrated how much the Hundred Years' War had changed in character by now. According to Christopher Allmand, "the days of Crécy and Poitiers were over."[23] Pontvallain "destroyed the reputation the English had for invincibility on the battlefield."[70] England continued losing territories Aquitaine until 1374, and as they lost land, they also lost the allegiance of local lords.[71] Pontvallain ended King Edward's short-lived strategy of promoting an alliance with Charles, King of Navarre[72] and marked the last of Great Companies by England in France; most of their original leaders had been killed, and although mercenaries were still considered useful, they were increasingly absorbed into the main armies of both sides.[73]

Five hundred years later, when the French lost Alsace-Lorraine to Germany, Pontvallain was used jingoistically as an example of another "spectacular recovery," when France had also wanted revenge.[74]

Notes

- ↑ Furthermore, it is not unlikely that the French nobility were in any case extremely averse to having Isabella as their queen. Not only was she in an adulterous, unmarried relationship with Roger Mortimer, but together they were widely believed to have instigated the murder of her husband, the previous King of England, Edward II.[6][7] It should also be noted that Edward was still only in his teenage years at this time, whereas the man chosen by the French, Philip of Valois, was twenty years older and so of greater experience.[8]

- ↑ Quoting Clifford Rogers: "English troops were fighting in three theatres in France (Aquitaine, Brittany and the north), and aso on the Scottish border, and in all four areas they won remarkable victories against heavier odds."[14] The Scots were allies of the French within the Auld Alliance, but at the Battle of Neville's Cross (1346) at which the Scottish King, David II was captured and taken to London.[14][15]

- ↑ This was policy. Other examples of a previously "retired" warrior being recalled to take up arms again is John Chandos, who had been killed in France the year before Knolles' campaign commenced, or Hugh Calveley, who of course was with Knolles.[20]

- ↑ In fact, he was following, almost exactly, in the footsteps of King Edward's great chevauchee of 1359.[22]

- ↑ On a previous campaign (that of 1357-60), Knolles used the same tactic with similarly profitable results. Michael Jones has described how Knolles' army "left a trail of ravaged villages, whose charred gables were known as 'Knolles' mitres'"-and how, as a result, Knolles made around £15,000 in booty.[2]

- ↑ The contemporary Chronique des regnes de Jean II et de Charles V describes how, even though "the said English set fire to a great number of villages around Paris... the King was advised, for the better, that they should not then be fought with."[25]

- ↑ This included the creation of reventions, or ransom districts, especially in the counties of Anjou and Maine. Likewise, the French behaved in similar fashion when they were attacked English-controlled territories.[29]

- ↑ However, this campaign would also suffer from divided leadership: The Earl of Pembroke, young and with "aristocratic arrogance"[21] refused to serve alongside Sir John Chandos, who, although of great military experience and fame,[21] was only a Knight Banneret in rank.[31] Pembroke's jealousy of Chandos was doubtless exacerbated by the fact that, as Jonathan Sumption put it, Pembroke "may have had the grander name but his inexperience showed."[32]

- ↑ An important aspect of the campaign: the French chronicler Pierre d'Orgemont, wrote (in his Chroniques des regnes de Jean II et Charles V) how, as Knolles' army marched through northern France burning the wheat and "great houses", the English "did not, however, burn anything for which a ransom was paid."[40]

- ↑ This was an innovative method of recruitment; no English government had attempted "contractual service without pay" before.[43] It has been described as the government attempting to reduce its own costs in warfare by relying on "the lure of profits" to make soldiering more attractive.[44] Likewise, if the system worked, it was because "the prospects of profits was dep-rooted in the military mentality and that the government was well aware of this and keen to take advantage of it."[45]

- ↑ This seemingly precise figure stems from the fact that the loan was actually accounted for in marks, and a mark was valued at one-third more than a pound; thus the total loan itself was actually 100,000 marks[65][66]–of which the single greatest amount came from the "famously rich" Richard, Earl of Arundel, who leant the King 40,000 marks, which is £26,667 (equivalent to £12,304,990 in 2016).[65] To put the cost of Knolles campaign in perspective, however, it has been estimated that the whole period of war, from its outbreak in 1369 to the 1375 Treaty of Bruges, may cost as much as £650,000 (equivalent to £299,930,392 in 2016).[67]

References

- 1 2 3 Sumption 2009, pp. 87–88.

- 1 2 3 4 Jones 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Tout 1965, p. 413.

- ↑ Taylor 2001, p. 155.

- ↑ Ormrod 2012, p. ch. 8.

- ↑ Brissaud 1915, pp. 329–30.

- ↑ Prestwich 2007, pp. 220–24.

- ↑ Taylor 2001, p. 157.

- ↑ Prestwich 1988, p. 298.

- ↑ Allmand 1989, p. 7.

- ↑ Allmand 1989, pp. 13–16.

- ↑ Allmand 1989, pp. 16–17.

- ↑ Neillands 1990, p. 117.

- 1 2 Rogers 2005, p. 127.

- ↑ Allmand 1989, p. 16.

- ↑ Allmand 1989, p. 17.

- ↑ Fowler 2001, p. 286.

- ↑ Ormrod 2012, p. 506.

- 1 2 3 Neillands 1990, p. 169.

- ↑ Fowler 2004.

- 1 2 3 Jack 2004.

- ↑ Sumption 2009, p. 84.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Allmand 1989, p. 22.

- 1 2 3 Fowler 2001, p. 290.

- 1 2 Rogers 2000, p. 190.

- ↑ Sumption 2009, pp. 84–5.

- ↑ Sumption 2009, p. 87.

- ↑ Fowler 2001, p. 292.

- ↑ Fowler 2001, p. 292 n.40.

- ↑ Sumption 2009, pp. 82–83.

- ↑ Barber 2004.

- ↑ Sumption 2009, p. 47.

- 1 2 3 Neillands 1990, p. 168.

- ↑ Nicholson 2003, p. 50.

- ↑ Burne 1999, p. 23.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fowler 2001, p. 294.

- 1 2 Fowler 2001, p. 289.

- 1 2 3 4 Fowler 2001, p. 293.

- ↑ Bell et al. 2011, p. 69.

- ↑ Rogers 2000, p. 189.

- ↑ Galbraith 1970, pp. 64–65.

- 1 2 3 4 Sumption 2009, pp. 89–90.

- ↑ Sherborne 1964, p. 7.

- ↑ Ambühl 2013, p. 100 n.10.

- ↑ Ambühl 2013, p. 100.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fowler 2001, p. 297.

- ↑ Bell et al. 2013, p. 69.

- ↑ Jones 2017, p. 88.

- ↑ Jaques 2006, p. 809.

- ↑ Coulton 1908, p. 244.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sumption 2009, pp. 89–91.

- 1 2 Sumption 2009, p. 90.

- 1 2 3 Sumption 2009, pp. 90–91.

- 1 2 Fowler 2001, p. 295.

- 1 2 3 Fowler 2001, p. 296.

- ↑ Galbraith 1970, p. 176.

- 1 2 Sumption 2009, p. 91.

- 1 2 Sumption 2009, p. 92.

- 1 2 Perroy 1965, p. 164.

- ↑ Sumption 2009, p. 93.

- ↑ Bell et al. 2011, p. 192.

- ↑ Bell et al. 2011, p. 203.

- ↑ Sumption 2009, p. 274.

- ↑ Ormrod 2012, p. 526.

- 1 2 Sumption 2009, pp. 70–71.

- ↑ Carlin & Crouch 2013, pp. 87–88.

- ↑ Prestwich 2003, p. 248.

- ↑ McKisack 1991, p. 145.

- ↑ Keen 1973, p. 255.

- ↑ Gillespie 2016, p. 170.

- ↑ Neillands 1990, p. 170.

- ↑ Ormrod 2012, p. 508.

- ↑ Nicholson 2003, p. 36.

- ↑ Kagay & Villalon 2008, p. 335.

Bibliography

- Allmand, C. (1989). The Hundred Years' War: England and France at War, c.1300-c.1450. (Cambridge Medieval Textbooks). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521319234.

- Ambühl, R. (2013). Prisoners of War in the Hundred Years War: Ransom Culture in the Late Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1107010942.

- Barber, R. (2004). "Chandos, Sir John (d. 1370)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 20 February 2018. Retrieved 20 February 2018. (Subscription required (help)).

- Bell, A. R.; Chapman, A.; Curry, A.; King, A.; Simpkin, D., eds. (2011). The Soldier Experience in the Fourteenth Century. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 9781843836742.

- Bell, A. R.; Curry, A.; King, A.; Simpkin, D. (2013). The Soldier in Later Medieval England. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199680825.

- Brissaud, J. (1915). A History of French Public Law. Boston: Little, Brown, &co. OCLC 837277616.

- Burne, A. H. (1999). The Agincourt War (repr. ed.). Ware: Eyre & Spottiswoode. ISBN 1840222115.

- Carlin, M.; Crouch, D. (2013). Lost Letters of Medieval Life: English Society, 1200-1250. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-07564.

- Coulton, G. G. (1908). Chaucer And His England. London: Methuen &co. OCLC 220948086.

- Fowler, K. (2001). Medieval Mercenaries: The Great Companies. I. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0631158868.

- Fowler, K. (2004). "Calveley, Sir Hugh (d. 1394)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 20 February 2018. Retrieved 20 February 2018. (Subscription required (help)).

- Galbraith, V. H. (1970). The Anonimalle Chronicle, 1333 to 1381: From a MS. Written at St Mary's Abbey, York (repr. ed.). Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 07190-0398-9.

- Gillespie, A. (2016). The Causes of War: Volume 2: 1000 CE to 1400 CE. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1849466455.

- Jack, R. I. (2004). "Hastings, John, thirteenth earl of Pembroke (1347–1375)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 20 February 2018. Retrieved 20 February 2018. (Subscription required (help)).

- Jaques, T. (2006). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: A Guide to 8,500 Battles from Antiquity through the Twenty-first Century: P-Z. III. Westport, CT: Greenwood. ISBN 0313335397.

- Jones, M. (2017). The Black Prince: The King That Never Was. London: Head of Zeus. ISBN 1784972932.

- Kagay, D.; Villalon, A., eds. (2008). The Hundred Years War: Pt. 2: Different Vistas. (History of Warfare). Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9004168214.

- Keen, M. H. (1973). England in the Later Middle Ages. Bristol: Head of Zeus. ISBN 0416759904.

- McKisack, M. (1991). The Fourteenth Century, 1307–1399 (repr. ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192852507.

- Neillands, R. (1990). The Hundred Years War. Padstow: Routledge. ISBN 041500148X.

- Nicholson, H. A. (2003). Medieval Warfare: Theory and Practice of War in Europe, 300-1500. London: Palgrave. ISBN 0333763319.

- Ormrod, W. M. (2012). Edward III. (Yale English Monarchs). Padstow: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300119107.

- Perroy, E. (1965). The Hundred Years War. Translated by Wells, W. B. USA: Capricorn (published 1945). p. 164. OCLC 773517536.

- Prestwich, M. (1988). Edward I. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06266-5.

- Prestwich, M. (2003). The Three Edwards: War and State in England, 1272-1377. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-30309-5.

- Prestwich, M. (2007). Plantagenet England:1225-1360. New Oxford History of England. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199226870.

- Rogers, C. J. (2000). The Wars of Edward III: Sources and Interpretations. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 9780851156460.

- Rogers, C. J. (2005). "Sir Thomas Dagworth in Brittany, 1346-7: Restellou and La Roche Derrien". In Rogers, C. J.; de Vries, K. The Journal of Medieval Military History. III. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. pp. 127–54. ISBN 978-1-84383-171-6.

- Sherborne, J. W. (1964). "Indentured Retainers and English Expeditions to France, 1369-80". The English Historical Review. 79: 718–46. OCLC 51205098.

- Sumption, J. (2009). The Hundred Years' War: Divided Houses. III (paperback ed.). London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 0571240127.

- Taylor (2001). "Edward III and the Plantaganet Claim to the French Throne". In J. Bothwell. The Age of Edward III. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. pp. 155–70. ISBN 978-1-903153-06-2.

- Tout, T. F. (1965). The History of England from the Accession of Henry III to the Reign of Edward III, 1216–1377. III (repr. ed.). New York: Haskell House. OCLC 499188639.

Coordinates: 47°45′04″N 0°11′32″E / 47.751156°N 0.192151°E