Battle of Isaszeg (1849)

| Battle of Isaszeg | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Total: 31,315 men - I corps: 10,827 - II corps: 8,896 - III corps: 11,592 99 cannons Did not participate VII corps: 14,258 men 66 cannons |

Total: 26,000 men - I corps: 15,000 - III corps: 11,000 72 cannons[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Total: 800–1,000 men |

Total: 373/369 men - 81/42 dead - 196/195 wounded - 96/132 missing and captured[2] | ||||||

The Battle of Isaszeg was a battle in the Spring Campaign of the Hungarian War of Independence from 1848 to 1849, fought on 6 April 1849 between the Austrian Empire and Hungarian Revolutionary Army supplemented by Polish volunteers. The Hungarians were victorious.

The Austrian forces were led by Field Marshal Alfred I, Prince of Windisch-Grätz, whilst the Hungarians were led by General Artúr Görgei. The battle was one of several engagements between the Hungarian Revolutionary Army and the Imperial counter-revolutionary main army and was one of the turning points of the Hungarian War of Independence. It precipitated a series of setbacks to the Habsburg Imperial Armies in April–May 1849, forcing them to retreat from occupied central and western Hungary towards the western border and convinced the Hungarian National Assembly to issue the Hungarian Declaration of Independence (from the Habsburg Dynasty). It also decided the fate of Alfred I, Prince of Windisch-Grätz, who was dismissed from the leadership of the Imperial forces in Hungary on 12 April 1849, six days after the defeat.

Background

After the Battle of Kápolna on 26–27 February 1849, the commander of the Austrian imperial forces, Alfred I, Prince of Windisch-Grätz, thought that he had destroyed the Hungarian revolutionary forces once and for all. He wrote on 3 March in his report sent to the imperial court in Olmütz, that: "I smashed the rebel hordes, and I will be in a few days in Debrecen (the temporary capital of Hungary)".[3] In spite of this he did not attack the Hungarian forces, lacking reliable information about the numbers facing him if he crossed the Tisza river and because of his caution lost the opportunity to win the war.

While he was deciding whether to attack or not, the Hungarian commanders, who were discontented with the disappointing performance of Lieutenant General Henryk Dembiński as high commander of the Hungarian forces, blaming him for losing the Battle of Kápolna, had started a "rebellion". At a meeting in Tiszafüred, they forced the Government Commissioner Bertalan Szemere to depose the Polish general and put Artúr Görgei in command instead. This so infuriated Lajos Kossuth, the President of the National Defense Committee (the interim government of Hungary), that he wanted to execute Görgei for rebellion. Finally, he was persuaded by the support of the Hungarian generals for Görgei to change his mind and accept the removal of Dembiński, although his dislike of Görgei prevented him from accepting Szemere's choice of successor, and he named Lieutenant General Antal Vetter high commander instead.[4] But Vetter became ill on 28 March, so after two days Kossuth was forced to accept Görgei as temporary high commander of the Hungarian main forces.[5] Those days and weeks of unrest, uncertainty and changes could have provided an excellent opportunity for Windisch-Grätz to cross the Tisza river and defeat the Hungarian army once and for all.

Windisch-Grätz's uncertainty was amplified by diversionary Hungarian attacks in the south at the Szolnok on 5 March and in the north, where on 24 March the 800-strong commando of Major Lajos Beniczky attacked the Imperial commando led by Colonel Károly Almásy at Losonc. They took half of Almásy's soldiers prisoners, and Almásy reported to Windisch-Grätz that he had been attacked by a 6,000-strong army. Because of this the Austrian marshal scattered his troops in all directions to prevent a surprise attack, his main concern being a bypass attack from the north, which he feared would relieve the ongoing siege of the fortress of Komárom and cut his supply lines.[6]

Meanwhile, on 30–31 March plans were made for the Hungarian army's Spring Campaign, led by General Görgei, to liberate the occupied Hungarian lands which lay to the west of the Tisza river, consisting of most of the territory of the Kingdom of Hungary. The Hungarian forces numbered some 47,500 soldiers and 198 cannons, organized in four army corps led by Generals György Klapka (I corps), Lajos Aulich (II corps), János Damjanich (III corps) and András Gáspár (VII corps).

The occupying Imperial forces, led by Windisch-Grätz, numbered 55,000 soldiers and 214 cannons and rockets and were organized in three army corps, led by Lieutenant Field Marshal Josip Jelačić (I corps), Lieutenant General Anton Csorich (II corps), General Franz Schlik (III corps), and the division led by Lieutenant General Georg Heinrich Ramberg.[7]

The Hungarian plan, elaborated by Antal Vetter, was for VII corps, under the command of András Gáspár, to divert the attention of Windisch-Grätz by making an attack from the direction of Hatvan, while the other three corps (I, II, III) would encircle the Austrian forces from the South West, cutting them off from the capital cities (Pest and Buda). According to the plan, VII corps had to stay at Hatvan until 5 April, and then reach Bag the following day. The attack on the Austrian forces had to occur from two directions at Gödöllő on 7 April, while I corps would advance to Kerepes and fall on the Austrians from behind, preventing them from retreating towards Pest.[8] Key to the plan was for the Austrians not to discover the Hungarian troop movements until they had completed their encirclement.[9]

Prelude

On 2 April, the preliminary fighting began when the Hungarian VII corps under András Gáspár clashed with the III Austrian corps led by Franz Schlik at the Battle of Hatvan. Schlik had wanted to obtain for Windisch-Grätz information about the positions and numbers of the Hungarian army and had moved towards Hatvan, but was defeated there by the VII Hungarian corps and forced to withdraw without accomplishing his purpose. Windisch-Grätz assumed that Schlik had come up against the main Hungarian army, and remained in the dark about the Hungarian army's true whereabouts.[10]

In the meanwhile the other three Hungarian corps moved, according to the campaign's plan, towards the South-West and on 4 April met with the Imperial I corps led by Josip Jelačić at the Battle of Tápióbicske and defeated them. Although György Klapka's attack at Tápióbicske had revealed where the Hungarian troops really were Görgei decided to continue with the original plan.[11]

But after the fighting on 4 April, Jelačić, the Ban of Croatia, had claimed to Windisch-Grätz that he had actually been victorious over the Hungarians, which misled the Field Marshal into giving him the order to pursue the Hungarians. They, rather than fleeing, were actually closing in around Windisch-Grätz's headquarters at Gödöllő as he was planning an attack on the Hungarian forces the following morning.[12] On 5 April he sent two companies of lancers, two companies of light horse and two rockets under the command of Lieutenant General Franz Liechtenstein on a reconnaissance mission to Hatvan but, after a skirmish with four companies of Hungarian hussars, they retreated none the wiser.[13] Fearing that the enemy's main forces would get around him from the south and cut his lines to the capital, or from the north, and liberate the fortress of Komárom from the ongoing Imperial siege, he sent the III corps of Franz Schlik to Gödöllő and the I corps of Jelačić southward to Isaszeg. Two brigades of the II corps led by Lieutenant General Ladislas Wrbna were also sent to Vác, and Lieutenant General Georg Heinrich Ramberg ordered to join him with his brigade. Two brigades remained in Pest.[14] Thus Windisch-Grätz had scattered his forces across a distance of 54 kilometers, making it impossible for them to effectively help each other (some of the troops were at more than a day distance from each others) in the event of a battle.[15]

Although the Hungarian front line was only 22 kilometers long, Görgei could only deploy two thirds of his troops in any point in the battle because of the specific orders he had given his generals regarding their movements prior to the attack on 7 April, the designated day of the battle. Gáspár was ordered to move from the north and occupy Bag and Damjanics's III corps had to move forward from Tápiószecső and occupy Isaszeg. Klapka's I corps also had to move towards Isaszeg, while one of his brigades had to take Pécel, and Aulich's II corps had orders to take up a position at Dány and Zsámbok.[16] Görgei's plan was for Gáspár to hold back the troops of the left wing of the Imperial army while the other three corps attacked them at Isaszeg. This would push them northwards from Pest, enabling the liberation of the Hungarian capital on the Eastern bank of the Danube. This forced Windisch-Grätz to choose between two bad options: to accept a battle where the Hungarians had superiority, or to retreat to Pest, which was hard to defend, being open to attacks from three directions. It also had only one unfinished bridge (the Chain Bridge), to allow his troops to cross the Danube to Buda on the other side should he need to retreat, a task which would have been impossible to achieve successfully. Windisch-Grätz chose the lesser of two evils.[17]

On the morning of 6 April at 6 o'clock, the Austrian troops retreated towards Gödöllő. Jelačić arrived to Isaszeg at 11 o'clock and set his camp on the heights near the village, reporting to Windisch-Grätz that Hungarian troops were following him from the south. The Field Marshal ordered him to find out the enemy strength, and if he had enough forces, to enter into battle with them.[18]

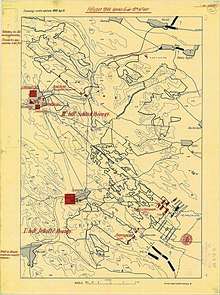

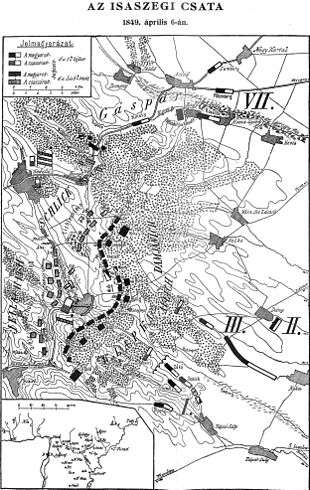

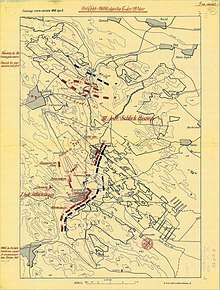

Battle

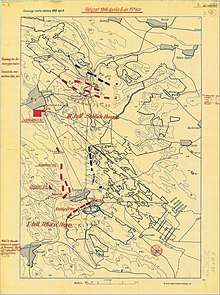

The date of the battle was planned for 7 April, and so on 6 April Görgei gave orders for his troops to move and occupy the designated forming up points in order to start the battle on the next day. He himself would be in Kóka (14.81 km from Isaszeg). However, when the troops moved to the places where they were supposed to wait, they encountered enemy soldiers and as a result the battle began early. The unexpected start of the battle caught both commanders by surprise, causing haste and confusion.[19]

Gáspár moved with his 14,258 troops and 66 cannons to Aszód, Tura and Bag on the bank of the river Galga at 12:30. He sent colonel György Kmety with a division to occupy Hévízgyörk, where they stumbled on the cavalry of Franz Schlik, and after the Imperials retreated, the Hungarians took stand. Gáspár did not move his troops forward even after hearing the gunfire of the battle, claiming that he was obeying the specific orders he had received from Görgei the previous day to remain in that position until the following day. This meant that his corps, the largest of the four Hungarian corps (I-10,817, II-8,896, III-11,592 men), was absent throughout the battle.[20]

At the same time the two corps of Klapka and Damjanich arrived in the vicinity of Királyerdő (King's Forest), which lay in front of Isaszeg to the East. Here the troops of Damjanich attacked the rear brigade of Jelačić's I corps, chasing it out of the forest to Isaszeg and setting fire to the forest in several places. Then the troops of Klapka attacked the brigade of Major-General Franz Adam Grammont von Linthal, chasing it towards Isaszeg. The Hungarian 34th and 28th battalions commanded by István Zákó and János Bobich arrived but the superiority of Jelačić's three foot brigades and three horse brigades caused the two battalions heavy losses and forced them to retreat towards the woods. The attack of the Austrian cuirassiers was finally repelled by the fusillade of Klapka's 44th and 47th battalions, then they were also attacked from the side by the brigade of Bódog Báthory Sulcz, and finally the two Hungarian battalions chased the Austrian kaiserjägers out from Királyerdő woods. But the Hungarian troops were prevented from leaving the woods themselves by the fusillade of the Croatian seressaners, positioned on a height near Isaszeg.[21]

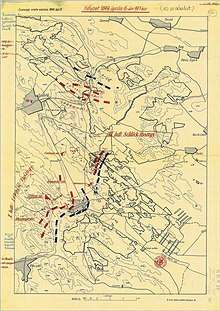

At 2 o'clock the units of the III corps of Damjanich crossed the wood, and after chasing the brigade of Daniel Rastić from the forest, positioned themselves at the western end of it. Rastić retreated across the Rákos creek, where they, together with the Schultzig division, who had been sent to help by Jelačić, repelled the attack of the Zákó brigade of Klapka's corps. This event set in disarray also the Bobich brigade from the same corps, causing them to retreat.[22]

At this moment Klapka, a very capable Hungarian general and one of the heroes of the Hungarian freedom war, inexplicably lost his head and left his commanders to their own devices. One of them, János Bobich, started an attack, but was repelled by the fusillade of the enemy.[23] Damjanich sent a brigade to help Klapka's embattled troops and sent another brigade to the northern end of the forest. He then positioned his cannons on high ground, and his cavalry on the nook of the forest, between his and Klapka's troops, right in the middle of the Hungarian front. Damjanich intended to attack with the purpose of relieving Klapka's embattled troops, but the latter, feeling that his situation was hopeless, started to withdraw his troops before the aid arrived. Damjanich remained in position, and when he saw the Austrian troops sent to pursue Klapka, sent one of his best units, the 9th battalion, together with the 3rd battalion, to help Klapka's troops. Klapka's two brigades (Zákó and Bobich), together with Damjanich's two battalions counterattacked, and pushed Jelačić's troops onto the heights on the right banks of the Rákos creek.[24]

Meanwhile, Aulich's II corps were stood still in Dány and Zsámbok, despite the fact that Aulich had received a message from Damjanich to hurry to the battlefield. Aulich, like Gáspár, insisted on obeying Görgei's orders of the day before to remain in position until the 7th. But after orders from Chief of the General Staff, Lieutenant-Colonel József Bayer he finally ordered to his troops to move towards Isaszeg.[25]

At 3 o'clock all the four Hungarian army corps were fighting in an uncoordinated way, as were their commanders. Görgei was still in Kóka, ignorant of what was going on, preparing for a battle that he thought would start the following day. At this point one of the Hungarian hussars arrived and informed him that the battle had begun and was about to be lost. Hearing this, Görgei mounted and hurried towards the battlefield.[26]

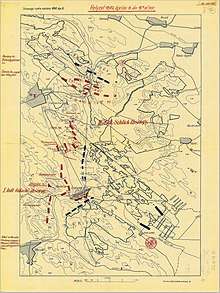

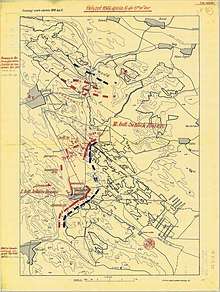

In the meanwhile Damjanich's troops continued their attack against the heights defended by Jelačić's troops, but they were caught by surprise from the north by the Franz Liechtenstein's division, sent by Schlick.[27] Damjanich had not secured his northern flank because he thought that Gáspár would attack and keep all of Schlick's troops in position. Now the Hungarian III corps was caught between two fronts, forcing Damjanich to retreat to Királyerdő, recover the lost ground there, and defend his position from the attacks of the Austrian infantry. At 4 o'clock, Klapka's two fighting brigades could not continue the fight alone, so they too retreated into the forest. Jelačić ordered a general attack against the Hungarians from all directions. This moment was a critical moment of the battle, because on the battle front stood 26,000 Imperial troops against 14,000 Hungarians, with only a half of the Hungarian artillery. Aulich's troops were in Dány, and Gáspár hadn't moved his VII corps. So the Hungarians were forced on to the defensive.[28]

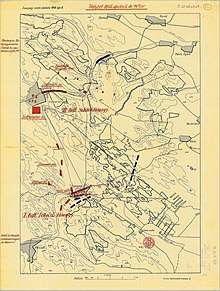

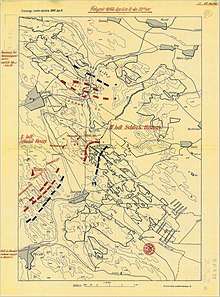

Görgei arrived at 4 o'clock at the eastern edge of the Királyerdő forest just as Aulich's corps arrived and was about to join the battle. He was also told that Gáspár's VII corps had occupied his position on the Galga rivers line. At this point Görgei made the mistake of not sending an order to Gáspár to advance, thinking that he was already doing so, whereas Gáspár was just standing in his position waiting for new orders. Görgei in his memoirs wrote that he was misinformed by the hussar who brought Gáspár's report, saying that his commander was advancing towards Gödöllő. Görgei now thought that he would easily encircle and destroy the main Imperial troops if Gáspár's corps attacked the Austrians from the north-west, as Damjanich's troops would hold the line in the forest, and Klapka would attack and chase the Austrians to the north.[29] But the plan failed because of Görgei's failure to send the message and Gáspár chose to remain in his position despite of hearing the cannonade. Had he taken the opportunity, it is possible that the war could have been decided there and then in the favour of the Hungarian cause. László Pusztaszeri explains that Gáspár's inactivity was due in part to his pro-Imperial feelings,[30] and that after the Declaration of the Dethronement of the Habsburg Dynasty by the Hungarian Parliament on 14 April 1849, he asked for permission to take leave, and ultimately never returned to serve in the Hungarian army.[31]

With the arrival of Görgei and Aulich the problems did not stop for the Hungarian army. Klapka was still retreating and the places he left empty on the margins of the forest could be occupied by the Austrian troops, cutting the Hungarian army in two. So Görgei distributed the battalions of Aulich's II corps in the following way among the endangered zones: four battalions to the right wing to help Damjanich, two in the middle to fill the gap created by Klapka's retreat, and the 61st battalion to help Klapka in the left wing. Görgei also consulted with Klapka, who wanted to continue his retreat, saying that his troops had run out of cartridges and were very tired, so "today is impossible to obtain victory, but tomorrow it will be possible again". But Görgei replied: "[...] the quickness of your infantry's retreat shows that they are not that tired, so they can try some bayonet attacks, and for these they have enough cartridges even if they have indeed really used them all. Today we have to win, or we can go back to the swamps of the Tisza! Only two solutions exist, we have no third. Damjanich is still holding out at his post, and Aulich is advancing - we must win!"[32] These words convinced Klapka to order his troops to move forward again and occupy Isaszeg.[33]

Görgei than hurried to the right flank, and told Damjanich that he had convinced Klapka to stop the retreat and attack. Damjanich showed no confidence that Klapka would accomplish what Görgei ordered him to do, but obeyed his commander and continued to fight against Liechtenstein's attacks. The eventual arrival of Aulich's four battalions created confusion, because the III corps troops thought that they were Austrians, and they started to shoot against each other, but they were stopped by Damjanich and Görgei shortly after. The long fights on the right flank disintegrated Damjanich's battalions, so he could not use the numerical superiority of his infantry (10 battalions) to start an attack against the five Austrian infantry battalions which faced them. This task was made impossible also by the numerical superiority of the Austrian cavalry, which had 34 companies against 17 on the Hungarian side, and by their artillery, as they had twice as many cannons as Damjanich. So on the right flank nothing special happened until around 23 o'clock.[34] But at this time the 25th, 48th, 54th, 56th battalions of Aulich's II corps, together with Damjanich's III corps, pushed the enemy towards Gödöllő.[35]

On the left flank victory came earlier, because around 7 o'clock the troops of Klapka and Aulich finally started the attack and managed to get out of the Királyerdő forest with the help of the Hungarian cannons, captured the burning village of Isaszeg with a bayonet attack, and also chased away the Imperial troops from the right banks of the Rákos creek. Jelačić's cavalry, made up of cuirassiers led by Major General Ferenc Ottinger, crossed the Rákos creek to start a counterattack, but the Hungarian artillery and the Hungarian cavalry, made up mainly by the hussars of Colonel József Nagysándor, chased them back. The chief of the general staff, József Bayer ordered I corps to chase the enemy, and to advance to Kerepes, but Klapka refused, pointing at the fatigue of his troops. The hastily retreating Imperials were only chased by the division of György Kmety, but he could not reach them.[36]

So in the end, of the Hungarian corps commanders it was Klapka, despite his initial setbacks, who decided the fate of the battle for the Hungarians. Windisch-Grätz, who at 7 o'clock thought he had won victory, had around 9 o'clock been forced to order his troops to retreat. Even after the battle was decided by the I corps attack, Görgei was still uncertain about its outcome, because in the right wing and the centre the fighting continued until late in the evening. Only when he moved to the left flank did he learn from Aulich that Jelačić's I corps had begun retreating towards Gödöllő and realised that the Hungarians had won the day.[37]

Aftermath

The battle of Isaszeg was, following the Battle of Kápolna, the second confrontation between the Hungarian revolutionary and the Habsburg imperial armies. Although it was not a crushing defeat for either of the combatants, it influenced the morale both of the victors and the defeated. While the Hungarian generals, except Ándrás Gáspár, showed the capability of taking decisions when they were on their own, the Imperial generals, other than Franz Schlik, failed from this point of view. Windisch-Grätz misunderstood the situation completely before the battle, scattering his troops, so the II corps commanded by Anton Csorich and the division of Georg Heinrich Ramberg could not participate in the battle. Although Görgei had made mistakes too, such as wrongly believing that Gáspár had joined the battle, he succeeded in organising the majority of his troops and winning the battle.[38] The battle of Isaszeg was in contrast to the Battle of Kápolna where, in a similar situation, Henryk Dembiński the Hungarian commander had failed to organise his troops on the battlefield, allowing Windisch-Grätz to win the battle.[39]

The most important result of the battle was that the military initiative was taken for two months by the Hungarian army, while the Habsburg army was defeated in a series of battles (Battle of Vác, Battle of Nagysalló, Battle of Komárom, Siege of Buda), and forced to retreat towards West. Also the Battle of Isaszeg played a decisive role in the dismissal of Windisch-Grätz from the lead of the Habsburg armies by the emperor on 12 April, who named Feldzeugmeister Ludwig von Welden in his place, although until his arrival his duties were fulfilled by Josip Jelačić.[40] However these changes in the command of the army did not produce a change in the military situation for the Austrian side, their situation continuing to worsen day by day because of the new defeats they suffered, which caused their retreat from almost all the territory they occupied between December and March in Hungary.[41]

In the day after the battle of Isaszeg, Lajos Kossuth, the President of the National Defense Committee arrived to Gödöllő and moved in the Grassalkovich-Palace, which was the headquarters of Windisch-Grätz until the previous day. Here he formulated the Hungarian Declaration of Independence, which declared the removal of the House of Habsburg from the leadership of Hungary and Hungary's total independence.[42] Although independence was declared on 14 April 1849 in Debrecen, it was decided in Gödöllő following the victories of the Spring Campaign, and in particular the Battle of Isaszeg.[43]

Also in Gödöllő was formulated the plan of the second phase of the Spring Campaign. This plan was based on making the Imperial high commanders believe that the Hungarian army wanted to liberate the capitals of Hungary: Pest and Buda, while in fact their main forces would move through the North, liberating the Hungarian fortress of Komárom, besieged since January by the Imperial forces. While the II corps, led by Lajos Aulich, remained in front of Pest, with the duty of misleading the Imperial forces, making such brilliant military maneuvers that the Austrian commanders thought that the Hungarian main forces were still in front of the capital planning to make a frontal attack against it, the I, III and VII corps accomplished the campaign plan perfectly, and on 26 April relieved the fortress of Komárom. This forced the main Austrian forces based in the capital, except 4,890 soldiers who were left to hold the fortress of Buda, to retreat to the Austrian border, thus liberating almost all of Hungary from the Austrian occupation.[44]

Legacy

The famous Hungarian Romantic novelist Mór Jókai made the Hungarian Revolution and Independence War the subject of his popular novel A kőszívű ember fiai (literally: The Sons of the Man with a Stone Heart, translated into English under the title: The Barons's sons) In the XIX and XX chapters, the Battle of Isaszeg is vividly presented as one of the main plot events of the novel, in which several of his main characters appear as fighters in the ranks of both the Hungarian and the Austrian army.[45] This novel was also adapted to a movie in 1965, having the same title (A kőszívű ember fiai) as the novel, and including the Battle of Isaszeg as one of its most important scenes.[46]

In the present day the battle is reenacted every year at its anniversary, 6 April, at Isaszeg and its environs.[47]

Notes

- ↑ Hermann 2013, pp. 20–23.

- ↑ Hermann 2013, pp. 25.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 244.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 244.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 263.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 271.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 268–269.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 270

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 270.

- ↑ Hermann 2013, pp. 14–16.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 218.

- ↑ Hermann 2013, pp. 17–18.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 274–275.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 275.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 275.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 275

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 252.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 252.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 224, 228.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 224, 229.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 225.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 255.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 226.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 255–256.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 226.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 226.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 226.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 256–257.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 226.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 258.

- ↑ Bóna 1987, pp. 157.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 227.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 227.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 227.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 259.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 259.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 227–228.

- ↑ Hermann 2013, pp. 25–26.

- ↑ Hermann 2013, pp. 26.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 285.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 314.

- ↑ G. Merva 2007, pp. 282.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 266–267.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 282–295.

- ↑ Jókai 1900, pp. 242–253.

- ↑ Men and Banners, Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Hadak Útja Lovas Sportegyesület 2015. Avagy ez történt eddig, ebben az évben….

Sources

- Hermann (ed), Róbert (1996). Az 1848–1849 évi forradalom és szabadságharc története ("The history of the Hungarian Revolution and War of Independence of 1848–1849) (in Hungarian). Budapest: Videopont. p. 464. ISBN 963-8218-20-7.

- Bóna, Gábor (1987). Tábornokok és törzstisztek a szabadságharcban 1848–49 ("Generals and Staff Officers in the War of Independence 1848–1849") (in Hungarian). Budapest: Zrínyi Katonai Kiadó. p. 430. ISBN 963-326-343-3.

- G. Merva, Mária (2007). Gödöllő története I. A kezdetektől 1867-ig ("The History of Gödöllő. I. From the Beginnings until 1867") (in Hungarian). Gödöllő: Gödöllői Városi Múzeum. p. 473. ISBN 978-963-86659-6-6.

- Hermann, Róbert (2001). Az 1848–1849-es szabadságharc hadtörténete ("Military History of the Hungarian War of Independence of 1848–1849") (in Hungarian). Budapest: Korona Kiadó. p. 424. ISBN 963-9376-21-3.

- Hermann, Róbert (2004). Az 1848–1849-es szabadságharc nagy csatái ("Great battles of the Hungarian War of Independence of 1848–1849") (in Hungarian). Budapest: Zrínyi. p. 408. ISBN 963-327-367-6.

- Hermann, Róbert (2013). Nagy csaták. 16. A magyar függetlenségi háború ("Great Battles. 16. The Hungarian Freedom War") (in Hungarian). Budapest: Duna Könyvklub. p. 88. ISBN 978-615-5129-00-1.

- Jókai, Maurus (1900). The Baron's Sons. London: The Walter Scott Publishing CO. LD. p. 378.

- Pusztaszeri, László (1984). Görgey Artúr a szabadságharcban ("Artúr Görgey in the War of Independence") (in Hungarian). Budapest: Magvető Könyvkiadó. p. 784. ISBN 963-14-0194-4.

External links

- (in Hungarian) Video animation about the Battle of Isaszeg

- (in Hungarian) Modern day reenactment of the battle, on 06.04.1014