Banyamulenge

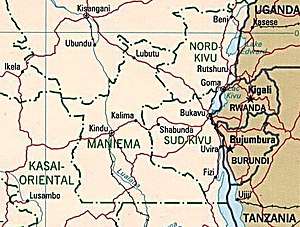

Banyamulenge, sometimes called "Tutsi Congolese", is a term historically referring to the ethnic Tutsi concentrated on the High Plateau of South Kivu, in the eastern region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, close to the Burundi-Congo-Rwanda border.

The Banyamulenge form a minority of the South Kivu population. Rival ethnic groups in the late 1990s claimed the Banyamulenge numbered no more than 35,000, while the Banyamulenge sympathizers claim up to ten times that number. The population of Banyamulenge in the early 21st century is estimated at between 50,000 and 70,000 by René Lemarchand[1] or by Gérard Prunier at around 60,000–80,000, a figure about 3–4 percent of the total provincial population.[2][3]

Lemarchand notes that the group represents "a rather unique case of ethnogenesis." The Banyamulenge of South Kivu are culturally and socially distinct from the Tutsi of North Kivu and the Tutsi who fled to South Kivu in the 1959–1962 Rwandan revolution. Most Banyamulenge speak Kinyarwanda, and they have a dialect that is different from other Kinyarwanda speaking groups.[1] The ambiguous political and social position of the Banyamulenge has been a point of contention in the province. The Banyamulenge played a key role in tensions during the run-up to the First Congo War in 1996–7 and Second Congo War of 1998–2003.

Origins and early political status

Compared to the history of the Rwandophones in North Kivu, composed of Hutu and Tutsi, the history of Banyamulenge is relatively straightforward. The Banyarwanda may have migrated from the Rwanda area in the seventeenth century.[4]

But the first significant recorded influx of Banyarwanda into South Kivu is dated to the 1880s.[5][6] Two reasons are given for their migration: the migrants were composed of Tutsi trying to avoid the increasingly high taxes imposed by Mwami Rwabugiri of the Kingdom of Rwanda. Secondly, the group was fleeing the violent war of succession that erupted in 1895 after the death of Rwabugiri.[7] This group was mostly Tutsi and their Hutu abagaragu (clients), who had been icyihuture (turned Tutsi), which negated interethnic tension. They settled above the Ruzizi Plain on the Itombwe Plateau. The plateau, which reached an altitude of 3000 meters, could not support large-scale agriculture, but allowed cattle grazing.[5]

Banyarwanda migrants continued to arrive, particularly as labour migrants during the colonial period. The Union Minière du Haut Katanga recruited more than 7000 workers from 1925 to 1929. From the 1930s, Congolese Banyarwanda immigrants continued coming in search of work, with a major influx of Tutsi refugees in 1959–1960 following the "Social Revolution" led by Hutu Grégoire Kayibanda. While the early migrants lived primarily as pastoralists in the high plains, colonial labour migrants moved to urban areas. Refugees were placed in refugee camps.[8] In 1924, the pastoralists received permission from colonial authorities to occupy a high plateau further south.[7]

The groups received further immigrants during the anti-Tutsi persecutions in 1959, 1964 and 1973.[2] Many Banyamulenge initially joined the Simba Rebellion of 1964–5, but switched sides when rebels, fleeing Jean Schramme's mercenaries and government troops, came onto the plateau and began killing the Banyarwanda's cattle for food. The Tutsi rose up, accepting weapons from the pro-Mobutu Sese Seko forces and assisting in the defeat of the remaining rebels. Because many of the rebels killed were from the neighbouring Bembe people, this incident created a lasting source of intra-group tension.[2] The government rewarded the Banyamulenge efforts on its behalf by appointing individuals to high positions in the capital Bukavu, while their children were increasingly sent to missionary schools. Starting at this time, Lemarchand asserts, "From a rural, isolated, backward community, the Banyamulenge would soon become increasingly aware of themselves as a political force."[1]

After the war, the group took advantage of a favourable political environment to expand their territory. Some moved south towards Moba port and Kalemi, while others moved onto the Ruzizi plain, where a few became chiefs among the Barundi through gifts of cattle. Still others went to work in the Bukavu, the provincial capital, or Uvira, a town experiencing a gold rush economic boom. These urban dwellers could make a fair living selling meat and milk from their herds to the gold diggers, though the group lacked the political connections to Kinshasa and the large educated class which was possessed by the North Kivu Banyarwanda.[9]

Unlike the Barundi, the Banyarwanda of South Kivu did not have their own Native Authority, and they were thus reliant upon the local chiefs of the area that they had settled. The pastoralists were located within three territoires: Mwenga, inhabited by the Lega people; Fizi of the Bembe people; and Uvira, inhabited by the Vira people, Bafuliro and Barundi.[10] The term "Banyamulenge" translates literally as "people of Mulenge", a groupement on the Itombwe plateau.[11] They chose the name "Banyamulenge" in the early 1970s to avoid being called "Banyarwanda" and seen as foreigners.[9] Ethnic tensions against the Tutsi rose following the end of the colonial period, as well as during the 1972 mass killing of Hutu in Burundi. In response the Tutsi appear to have attempted to distance themselves from their ethnicity as Rwandans and lay claim to a territorial identity as residents of Mulenge. As they moved, they continued this practice. Some Tutsi Banyarwanda in South Kivu call themselves the Banya-tulambo and Banya-minembwe, after the places they were located.[11]

Political tensions (1971–1992)

After 1971, such practices were considered increasingly more controversial. The 1971 Citizenship Decree by President Mobutu Sese Seko granted citizenship to the Banyarwanda who had arrived as refugees from 1959 to 1963. However, some leaders, such as Chief of Staff Barthélémy Bisengimana, were concerned that this change was an alarming sign of the growing influence of the Banyarwanda in the administration.[12] In 1976, the word "Banyamulenge" first came into wide usage after Gisaro Muhazo, a South Kivutian minister of parliament, began an initiative to reclassify the Banyamulenge of Mwenga, Fizi, and Uvira into a single administrative entity. Muhazo's attempt failed, but the term he introduced remained. Over decades, it became used as a catchall label for the Kivutian Tutsi.[1]

In reaction to the apparently growing influence of the Banyamulenge, the majority ethnicities, particularly the Nande and Hunde of North Kivu, focused on dominating the 1977 legislative elections. Once accomplished, they passed the 1981 Citizenship Bill, stating that only people who could prove descent from someone resident in Congo in 1885 would qualify for citizenship. From the perspective of the "indigenous" ethnicities, such as the Bafuliro, the name "Banyamulenge" was a claim to indigeneity in Mulenge, but the Bafuliro themselves claimed "ownership" of this area.

However, the bill proved difficult to implement by the time of the 1985 provincial assembly elections, so the "indigenous" Kivutian majority came up with an ad hoc measure: Banyarwanda were allowed vote in elections, but not to run for political office. This appeared to aggravate the situation, as those Banyarwanda who qualified as citizens under the 1981 law still found their political rights curtailed. Some Banyarwanda, particularly Tutsi, smashed ballot boxes in protest.[13] Others formed Umoja, an organisation of all Congolese Banyarwanda. However, the increasingly tensions within the Banyarwanda led to the division of the organisation into two Tutsi and Hutu groups in 1988.[12]

The 1991 Sovereign National Conference (CNS) was a sign of the increasing coherence of the anti-Mobutu forces and came as the Congolese Banyarwanda were in a state of heightened tension. Following the beginning of the Rwandan Civil War in 1990, many young Tutsi men in Kivu decided to cross the border to join the Tutsi-dominated rebel Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) in its fight against the Hutu-dominated Rwandan government. In response, the Mobutu government implemented Mission d'Identification de Zaïrois au Kivu to identify non-Zairean Banyarwanda, using the end of the Berlin Conference as the division point. Many Banyarwanda whose families had come as colonial labourers were classified as aliens, resulting in yet more youth joining the RPF. The overall effect of the CNS was to strengthen the tendency of "indigenous" Congolese to differentiate between Tutsi from Hutu, and lump together all Tutsi Banyarwanda as "Banyamulenge". It also underlined the fragility of their political position to the Banyamulenge. Within the Banyarwanda in the Kivus, the Hutu began defining themselves as "indigenous" in comparison to the Tutsis, who were increasingly seen as owing their allegiance to the foreign groups.[14]

Conflict (1993–1998)

In 1993, the issue of land and indigenous claims in the Kivus erupted into bloody conflict. Hutu, and some Tutsi, landlords began buying the lands of poor Hutu and Bahunde of the Wanyanga chiefdom in Masisi, North Kivu. After being displaced, one thousand people went to Walikale, demanding the right to elect their own ethnic leaders. The Banyanga, insisting that only "indigenous people" could claim this customary right, began fighting with the Hutu.

The one thousand returned to Masisi, where the Hutu landlords, and Banyarwanda in general, supported the claim of Banyarwanda to "indigenous" rights. The government sent in the Division Spéciale Présidentielle (DSP) and Guard Civile to restore order. Ill-supplied, the security forces were forced to live off the local population: the DSP off the rich Hutu and the Guard Civile off the Bahunde and ordinary Hutu. The DSP appeared to be protecting the rights of the "non-indigenous" (primarily Hutu) against the "indigenous" (primarily Bahunde), sparking outrage and increasing the scope of the conflict. One estimate is that between 10,000 and 20,000 people were killed; another 200,000 people were forced to flee their homes.[15]

In late 1993, about 50,000 Burundian refugees from the Burundi Civil War began streaming into primarily South Kivu. They were followed the next year by almost one million mostly Hutu refugees from the Rwandan Genocide, creating the Great Lakes refugee crisis. The Hutu government responsible for the genocide came with the refugees; they turned the camps into armed bases from which they could launch attacks against the newly victorious RPF government in Rwanda. The influx of refugees dramatically changed the situation of the Banyamulenge.

The Congolese Tutsi in North Kivu were threatened by the new armed Hutu camps, while the newly established Tutsi government in Rwanda gave them a safe place to go. Their peril was underlined by a commission led by Mambweni Vangu, who declared that all Banyarwanda were refugees and must return to Rwanda. In April 1995, Anzuluni Mbembe, the co-speaker of the Parliament of Congo, signed a resolution stating that all Banyamulenge were recent refugees (regardless of how long they had lived in the Congo) and providing a list of Banyamulenge who would be expelled from the country. Between March and May 1996, the remaining Tutsi in Masisi and Rutshuru were identified and expelled into refugee camps in Gisenyi. The Bahunde, forced out by the Hutu, also took refuge there.[16]

The situation in South Kivu took longer to develop. Once the 1994 refugees arrived, local authorities began appropriating Banyamulenge-owned property in the valley with the support of Mbembe. Threatened by both the armed Hutus to the north and a Congolese army appropriating property and land, the Banyamulenge of South Kivu sought cross-border training and supply of arms from the RPF. As threats proliferated, each Native Authority formed its own militia. Finally, in November 1996, the RPF-backed Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo (AFDL), which the Banyamulenge militias joined, crossed the border and dismantled the camps, before continuing on to Kinshasa and overthrowing Mobutu.[17] The ranks of the AFDL were composed in large part by Banyamulenge, who filled most of the administrative positions in South Kivu after the fall of Bukavu.[18]

As documented in the DRC Mapping Exercise Report by the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, the success of the invasion led to revenge killings by the Tutsi Banyarwanda against their opponents. Perhaps six thousand Hutu were purged in the week following the AFDL capture of the town.[17] It was worse in South Kivu, as Banyamulenge settled local scores and RPF soldiers appeared to conflate the génocidaires with the Hutu with the "indigenous" Congolese. One intellectual in Bukavu who was otherwise sympathetic to the Banyamulenge claim to citizenship stated:

The Banyamulenge conquered their rights by arms but the rift between them and the local population has grown. The attitude of the Tutsi soldiers—during and after the war has made them more detested by the population due to the killings, torture. For example, they will go into the village, raid all the cattle, tell the population—since when have you learned to keep cattle; we are cattle; we know cattle. In Bukavu, they went into and stole from houses. Not so much in Goma. The result is the population is increasingly getting concerned over the question of the Tutsi presence.[19]

Second Congo War (1998–2003)

The situation became more polarised with the beginning of the Second Congo War in 1998. Those who had carried out the massacres of Hutu became part of the ruling military forces in the Kivus. Meanwhile, the Congolese government of Laurent Kabila urged the "indigenous" population to fight not only the invading RPA ( Rwandan Patriotic Army ), but also the Congolese Tutsi civilians, the mostly affected being Banyamulenge. Matching actions to words, Kabila armed "indigenous" militiasMai-Mai and Congolese Hutu militias, as well as the Génocidaires (those who carried out mass killings during and after the 1994 Rwandan Genocide, in which close to a million Rwandans, primarily Tutsis, were murdered by their Hutu neighbors.) in response to the RPF's supplying arms to the Banyamulenge.[20] The two Mai-Mai groups most active against the Banyamulenge were the Babembe and Balega militias.

The various Banyamulenge militias and the Rwandan government forces became separate because of disagreements over motives of the uprising after the creation of RCD-Goma. In early 2002, extensive fighting took place on the high plateau of South Kivu after Commandant Patrick Masunzu, then a Tutsi officer in the Rwandan-backed Rally for Congolese Democracy-Goma (RCD-Goma) rebel movement, gathered Banyamulenge support in an uprising against the RCD-Goma leadership.[21]

By 2000, the Banyamulenge were hemmed into the high plateau by Congolese Mai-Mai, the Burundian Forces for the Defense of Democracy, and the Rwandan Hutu Armée de Libération du Rwanda (ALiR). They were unable to carry out basic economic activities without the security provided through the RCD-Goma. Numerous families fled to the relative safety of the Burundian capital of Bujumbura. Nevertheless, Banyamulenge made up much of the RCD military wing, the Armée Nationale Congolaise (ANC), and controlled the towns of Fizi, Uvira, and Minembwe, which was recently declared a "commune" among many others in 2018.

In August 2004, 166 Banyamulenge refugees were massacred at a refugee camp in Gatumba, Burundi by a force composed mostly of National Liberation Front rebels.[22] Vice-President Azarias Ruberwa, a Munyamulenge, suspended his participation in the transitional government for one week in protest, before being persuaded to return to Kinshasa by South African pressure.

See also

Notes and references

- 1 2 3 4 Lemarchand, 10

- 1 2 3 Prunier, 51–52

- ↑ Lemarchand states the figure of 400,000 given by Joseph Muembo [Les Banyamulenges, (Limete: Impremerie Saint Paul, 1997), 26 (in French)] is "grossly exaggerated." Lemarchand, 10

- ↑ Historian Alexis Kagame claims that soldiers under Mwami Kigeli II of Rwanda (1648–1672) settled across the Ruzizi River, but Prunier asserts that "Kagame has a tendency to exaggerate the power of the old Rwanda kingdom." Prunier, 51 & 381

- 1 2 Prunier, 51

- ↑ Lemarchand notes that the pre-colonial arrival of the Tutsi in the Kivus is generally agreed to among historians, but is "vehemently contested, however, by many Congolese intellectuals." Lemarchand, 10.

- 1 2 Mamdani, 250

- ↑ Mamdani, 247–248

- 1 2 Prunier, 52

- ↑ Mamdani, 248

- 1 2 Mamdani, 248–249

- 1 2 Mamdani, 252

- ↑ Mamdani, 243–245

- ↑ Mamdani, 245–247

- ↑ Mamdani, pp. 252–253

- ↑ Mamdani, 253–255

- 1 2 Mamdani, 255–259

- ↑ Lemarchand, 10–11

- ↑ Mamdani, 259–260

- ↑ Mamdani, 260–261

- ↑ Responses to Information Requests (RIRs): "Current treatment of the Banyamulenge people in the Democratic Republic of Congo" Archived 10 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine., Research Directorate of the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, UN High Commission on Refugees, June 2003

- ↑ See "Burundi: The Gatumba Massacre – War Crimes and Political Agendas" (PDF). (297 KiB), Human Rights Watch Briefing Paper, September 2004

References

- Lemarchand, René (2009). The Dynamics of Violence in Central Africa. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-4120-4.

- Mamdani, Mahmoud (2001). When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-05821-0.

- Prunier, Gérard (2009). Africa's World War: Congo, the Rwandan Genocide, and the Making of a Continental Catastrophe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-537420-9.

Further reading

- Hiernaux, J. "Note sur les Tutsi de l'Itombwe," Bulletin et Mémoires de la société d'anthropologie de Paris 7, series 11 (1965) (in French)

- Vlassenroot, Koen. "Citizenship, Identity Formation & Conflict in South Kivu: The Case of the Banyamulenge", in Review of African Political Economy – Vol. 29 No. 93/94, (Sep/Dec 2002), pp 499–515

- Weis, G. Le pays d'Uvira (Brussels: ASRC, 1959) (in French)

- Willame, J.C. Banyarwanda et Banyamulenge: Violences ethniques et gestion de l'identitaire au Kivu, Brussels: CEDAF, 1997. (in French)