Baby Face (film)

| Baby Face | |

|---|---|

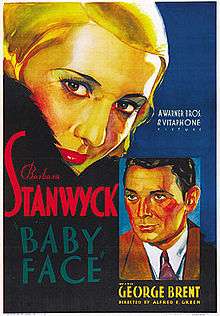

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Alfred E. Green |

| Produced by |

William LeBaron Raymond Griffith |

| Screenplay by |

Gene Markey Kathryn Scola |

| Story by | Mark Canfield |

| Starring |

Barbara Stanwyck George Brent |

| Music by |

Harry Akst Ralph Erwin Fritz Rotter Beth Slater Whitson |

| Cinematography | James Van Trees |

| Edited by | Howard Bretherton |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. Pictures, Inc. |

Release date |

|

Running time |

71 mins. 75 mins. (restored version) |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $187,000 (estimated) |

Baby Face is a 1933 American pre-Code dramatic film directed by Alfred E. Green, starring Barbara Stanwyck as Lily Powers, and featuring George Brent. Based on a story by Darryl F. Zanuck (under the pseudonym Mark Canfield), this sexually-charged Pre-Code Hollywood film is about an attractive young woman who uses sex to advance her social and financial status. Twenty-five-year-old John Wayne plays a supporting role as one of Powers' lovers.

Marketed with the salacious tagline "She had it and made it pay",[1] the film's open discussion of sex made it one of the most notorious films of the Pre-Code Hollywood era[1] and helped bring the era to a close. Mark A. Vieira, author of Sin in Soft Focus: Pre-Code Hollywood[2] has said, "Baby Face was certainly one of the top 10 films that caused the Production Code to be enforced."[3]

Plot

Lily Powers works for her mean father, Nick, in a speakeasy during Prohibition. Since the age of 14, her father has had her sleep with many of his customers. The only man she trusts is Cragg, a cobbler who admires Friedrich Nietzsche and advises her to aspire to greater things. Lily's father is killed when his still explodes. Cragg tells Lily to move to a big city and use her power over men. She and her African-American co-worker and friend Chico hop a freight train to New York City, but are discovered by a railroad worker who threatens to have them thrown in jail. She says, "Wait ... can't we talk this over?" It is strongly implied that she has sex with him to change his mind.

In New York, Lily goes inside the Gotham Trust building. She seduces the personnel worker to land a job. Her progress, sleeping her way to the top, is shown in a recurring metaphor.

In the filing department, Lily begins an affair with Jimmy McCoy Jr., who recommends her for promotion to his boss, Brody. She quickly seduces Brody and is transferred to the mortgage department. Brody and Lily are caught in flagrante delicto by a rising young executive, Ned Stevens. Brody is fired, but Lily claims Brody forced himself on her. Ned believes her, and gives her a position in his accounting department.

Although Ned is engaged to Ann Carter, the daughter of First Vice President J. P. Carter, Lily quickly seduces him. When Ann calls to say she will be visiting, Lily arranges to have Ann see her embracing Ned. Ann runs crying to her father, who tells him to fire Lily. Ned refuses, so J.P. goes to see Lily himself. Lily claims she had no idea Ned was engaged and that he was her first boyfriend. She seduces J.P., and he installs her in a lavish apartment, with Chico as her maid. Ned, pining for Lily, tracks her down on Christmas Day, but she spurns him. He later returns to her apartment to ask her to marry him, but finds J.P. there. He shoots and kills J.P. and then himself.

Courtland Trenholm, the grandson of Gotham Trust's founder, is elected bank president to handle the resulting scandal. The board of directors, learning that Lily has agreed to sell her diary to the press, summons her to a meeting. She tells them she is a victim of circumstance who merely wants to make an honest living. The board offers her $15,000 to withhold her diary, but Courtland, seizing on her claim that she simply wants to restart her life, instead offers her a position at the bank's Paris office. She reluctantly accepts.

When Courtland travels to Paris on business some time later, he is surprised and impressed to find Lily not only still working there but promoted to head of the travel bureau. He soon falls under her spell and marries her. Unlike her previous conquests, Courtland sees she is scheming and self-centered, but admires her spirit nonetheless. While on their honeymoon, he is called back to New York. The bank has failed due to mismanagement, which the board falsely pins on Courtland. He is indicted, and tells Lily he must raise a million dollars to finance his defense. He asks her to cash in the bonds, stocks and other valuables he gave her, but she refuses and books tickets back to Paris.

While waiting for the ship to leave, she changes her mind and rushes back to their apartment. When she arrives, she discovers Courtland has shot himself. On the way to the hospital, the attendant assures her that he has a good chance of survival. Lily drops her briefcase, spilling money and jewels on the floor. When the attendant points this out, she tearfully tells him she does not care. Courtland opens his eyes, sees Lily, and smiles at her.

Some time later, at a meeting of the bank's board of directors, one of them announces that the Trenholms have moved to Pittsburgh, where Courtland works at a steel mill.

Cast

- Barbara Stanwyck as Lily Powers

- George Brent as Courtland Trenholm

- Donald Cook as Ned Stevens

- Alphonse Ethier as Adolf Cragg, a cobbler

- Henry Kolker as J.P. Carter

- Margaret Lindsay as Ann Carter

- Arthur Hohl as Ed Sipple

- John Wayne as Jimmy McCoy Jr., one of Lily's early bank conquests.[4]

- Robert Barrat as Nick Powers, Lily's father

- Douglass Dumbrille as Brody (as Douglas Dumbrille)

- Theresa Harris as Chico, Lily's maid/friend

- Nat Pendleton as bar patron

Production

This film was Warner Bros.' answer to MGM's Red-Headed Woman (1932), another pre-Code Hollywood film with a similar theme, starring Jean Harlow.[2] Production head Darryl F. Zanuck wrote the treatment for the film and sold it to Warner Bros. for a dollar. The Great Depression was having a devastating effect on the film industry at the time, and many studio personnel were voluntarily taking salary cuts to help. Zanuck did not need the money because he was drawing a weekly salary of $3,500.[2] He later left Warner Bros. and became the legendary head of 20th Century Fox.

Aside from its depiction of a seductress, the film is notable for the "comradely" relationship Lily has with African-American Chico.[5]

A publicity still from this film aptly shows Barbara Stanwyck posing next to a stepladder.[6]

An instrumental version of the 1926 hit song "Baby Face" is played over the opening credits and during a scene with the actress at her boarding house.

Reception

Reviews

The New York Times panned the film, calling it "an unsavory subject, with incidents set forth in an inexpert fashion."[7]

Censorship

Sexual content

Because the New York State Censorship Board rejected the film's original version in April 1933, the film was softened by cutting out some material (such as Lily's study of Nietzschean philosophy as well as various sexually suggestive shots). The producers also inserted new footage and tacked on the ending in which Lily has changed and is content to live a modest lifestyle.[8] In June 1933 the New York Censorship Board passed the revised version, which then had a successful release.[3]

The uncensored version remained lost until 2004, when it resurfaced at a Library of Congress film vault in Dayton, Ohio. George Willeman is credited with the discovery.[9] The restored version premiered at the London Film Festival in November 2004. In 2005 it was deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" and selected for preservation in the United States Library of Congress National Film Registry[10] and also was named by Time.com as one of the 100 best movies of the last 80 years.[11]

Altered speech

Early in the film, Lily seeks the advice of the only man she trusts, a cobbler played by Alphonse Ethier. He reads a passage from a book by the philosopher Nietzsche. The first version of the cobbler's speech that did not pass New York State Censorship was as follows:[2]

A woman, young, beautiful like you, can get anything she wants in the world. Because you have power over men. But you must use men, not let them use you. You must be a master, not a slave. Look here — Nietzsche says, "All life, no matter how we idealize it, is nothing more nor less than exploitation." That's what I'm telling you. Exploit yourself. Go to some big city where you will find opportunities! Use men! Be strong! Defiant! Use men to get the things you want![2]

After much discussion with Zanuck, Joseph Breen of the Studio Relations Committee suggested that the film could pass by making the cobbler a spokesman for morality. Breen himself rewrote the scene as follows (the revised lines are italicized):

A woman, young, beautiful like you, can get anything she wants in the world. But there is a right way and a wrong way. Remember, the price of the wrong way is too great. Go to some big city where you will find opportunities! Don't let people mislead you. You must be a master, not a slave. Be clean, be strong, defiant, and you will be a success.[2]

The new lines were dubbed onto an over-the-shoulder shot of the cobbler. This was one of several changes that allowed the film to pass the Censorship Board.[2]

See also

References

- 1 2 Turan, Kenneth. Never Coming to a Theater Near You: A Celebration of a Certain Kind of Movie. Public Affairs 2004. ISBN 1-58648-231-9. Pg. 375

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Vieira, Mark A. (1999). Sin in Soft Focus: Pre-Code Hollywood. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. pp. 148–149. ISBN 0-8109-4475-8.

- 1 2 "A Wanton Woman's Ways Revealed, 71 Years Later", Dave Kehr, New York Times, January 9, 2005

- ↑ Jeff Stafford. "Spotlight: Baby Face". Turner Classic Movies (tcm.com).

- ↑ "Baby Face (1933)". moviediva.com.

- ↑ Sin in Soft Focus, p. 157

- ↑ M.H. (June 24, 1933). "A Woman's Wiles". The New York Times.

- ↑ Article by Betsy Sherman, April 7, 2006, WBUR radio

- ↑ Boliek, Brooks (December 28, 2005). "'Hidden film history' unearthed". hollywoodreporter.com.

- ↑ Library of Congress press release, December 20, 2005, re films added to National Film Registry

- ↑ "Baby Face (1933)". Time magazine. February 12, 2005.

Bibliography

- Doherty, Thomas Patrick. Pre-Code Hollywood: Sex, Immorality, and Insurrection in American Cinema 1930–1934. New York: Columbia University Press 1999; ISBN 0-231-11094-4

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Baby Face (film). |

- Baby Face on IMDb

- Review by Chris Dashiell from July 2000 (pre-restoration)

- Blog entry from Filmradar.com, May 20, 2005

- Article by Kendahl Cruver, Senses of Cinema, September 2005

- "Revealing the Racy Original Cut of 'Babyface'", Scott Simon, January 29, 2005

- "Profile and Review: Forbidden Hollywood", Review by J.C. Loophole, The Shelf