David and Bathsheba (film)

| David and Bathsheba | |

|---|---|

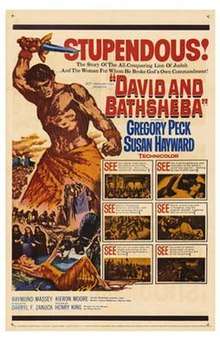

Original film poster | |

| Directed by | Henry King |

| Produced by | Darryl F. Zanuck |

| Written by | Philip Dunne |

| Starring |

Gregory Peck Susan Hayward Raymond Massey Kieron Moore James Robertson Justice |

| Music by |

Alfred Newman Edward Powell |

| Cinematography | Leon Shamroy |

| Edited by | Barbara McLean |

| Distributed by | 20th Century-Fox |

Release date |

|

Running time | 116 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $2.17 million[1] |

| Box office | $7.1 million (est. US/ Canada rentals)[2][3] |

David and Bathsheba is a 1951 historical Technicolor epic film about King David made by 20th Century Fox. It was directed by Henry King, produced by Darryl F. Zanuck, from a screenplay by Philip Dunne. The cinematography was by Leon Shamroy. Gregory Peck stars as King David and the film follows King David's life as he adjusts to ruling as a King, and about his relationship with Uriah's wife Bathsheba (Susan Hayward). Goliath of Gath was portrayed by 203 cm-tall (6'8") Lithuanian wrestler Walter Talun.

Summary

King David was the second king of Israel and this film is based on the second Old Testament book of Samuel from the Bible. When the Ark of the Covenant is brought to Jerusalem, a soldier reaches out to steady it and is struck dead. While the prophet Nathan declares this the will of God, a skeptical David pronounces it the result of a combination of heat-stroke and too much wine. David becomes attracted to Bathsheba who is the wife of Uriah, one of David's soldiers. The attraction is mutual although both know an affair would break the law of Moses. When Bathsheba discovers she is pregnant by David, the King sends for Uriah hoping he will spend time with his wife to cover her pregnancy. David's wife Michal who is aware of the affair, tells David that Uriah did not go home but slept at the castle as a sign of loyalty to his King. Frustrated, David orders Uriah to be placed on the battle's front and for the troops to withdraw leaving him to die. Uriah is reported dead and David sends a dispatch to tell Bathsheba so they can plan their marriage. Nathan the prophet advises David the people are dissatisfied with his leadership and desire his sons to rule. Nathan tells David he has forgotten that he is a servant of the Lord. David marries Bathsheba. A drought hits Israel. David's and Bathsheba's baby dies. Nathan returns to tell David that God is displeased with his sin. He will not die as the law demands, but he will be punished through misfortune in his family. David takes responsibility but insists Bathsheba is blameless. But the people want Bathsheba killed. David makes plans to save Bathsheba, but she tells David she is not blameless. They are both at fault. David is reminded of the Lord and quotes Psalm 23 as he plays his harp. David tells Bathsheba she will not die and is willing to accept God's justice for himself. Repentant, David, seeking relief from the drought and forgiveness reaches out to touch the Ark presuming that he will die like the soldier. A clap of thunder is heard and there are flashbacks to David's youth depicting his anointing by Samuel and his battle with Goliath. King David removes his hands from the Ark as rain falls on the dry land. Screenwriter Dunne said he "left it to the audience to decide if the blessed rain came as the result of divine intervention or simply of a low-pressure system moving in from the Mediterranean."[4]

Cast

- Gregory Peck as King David

- Susan Hayward as Bathsheba

- Kieron Moore as Uriah

- Raymond Massey as Nathan

- James Robertson Justice as Abishai

- Jayne Meadows as Michal

- John Sutton as Ira

- Dennis Hoey as Joab

- Walter Talun as Goliath

- Francis X. Bushman as King Saul

- Leo Pessin as Young David

- Paul Newlan as Samuel

- Holmes Herbert as Jesse

- George Zucco as Egyptian Ambassador (uncredited)

- Gwen Verdon as Specialty dancer (uncredited)

Production

While Twentieth Century-Fox Film Corp. owned the rights to the 1943 book David written by Duff Cooper, the film is not based on that book. Zanuck also owned the rights to a 1947 Broadway play called "Bathsheba". Seeing the success of C. B. DeMille's Samson and Delilah, Zanuck commissioned Philip Dunne to write a script based on King David. Dunne conceived it as a modern-type play exploring the corruption of absolute power. The film is noticeably devoid of the epic battles and panoramas frequently seen in biblical movies.

Zanuck opted to use stars already under contract to 20th Century-Fox. The production of the film started on November 24, 1950 and was completed in January 1951 (with some additional material shot in February 1951). The film premiered in New York City August 14, and opened in Los Angeles August 30, before opening widely in September 1951.[5] It was shot entirely in Nogales, Arizona.

The musical score was by Alfred Newman, who, for the bucolic scene with the shepherd boy, used a solo oboe in the Lydian mode, drawing on long established conventions linking the solo oboe with pastoral scenes and the shepherd's pipe. To underscore David's guilt-ridden turmoil in the Mount Gilboa scene, Newman resorted to a vibraphone, which Miklós Rózsa used in scoring Peck's popular 1945 Spellbound, in which he played a no less disturbed patient suffering from amnesia.[6]

Reception

The film earned an estimated $7 million at the US box office in 1951, making it the most popular movie of the year.[7]

The New York Times described the film as "a reverential and sometimes majestic treatment of chronicles that have lived three millenia.[8] It praises Dunne's screenplay and Peck's "authoritative performance", while noting the part largely overshadows the rest of the cast.

The film sparked protests in Singapore over what the Muslim community considered an unflattering portrait of David, considered an important prophet in Islam, as a hedonist susceptible to sexual overtures.[9]

Jon Solomon found the film's first half rather slow-paced, but gained momentum, and Peck "convincing as a once-heroic monarch who must face an angry constituency and atone for his sins." [10] He noted that this was different from other biblical epics in that the protagonist faced a religious and philosophical issue rather than the overdone military or physical crisis.

Commentary

David and Diana Garland argue that, "Taking remarkable license with the story, the screen writers changed Bathsheba from the one who is ogled by David into David's stalker." They go on to suggest that "the movie David and Bathsheba, written, directed and produced by males, makes the cinematic Bathsheba conform to male fantasies about women."[11]

However, in giving Bathsheba a more active role, Adele Reinhartz found that "it reflects tensions and questions about gender identity in America in the aftermath of World War II, when women had entered the work force in large numbers and experienced a greater degree of independence and economic self-sufficiency. ...[Bathsheba] is not satisfied in the role of neglected wife and decides for herself what to do about it."[12] Susan Hayward was later quoted as having asked why the film was not called Bathsheba and David.[13]

Awards

The film was nominated for five Academy Awards:[14]

- Best Art Direction (Lyle R. Wheeler, George Davis, Thomas Little, and Paul S. Fox)

- Best Cinematography (Leon Shamroy)

- Best Costume Design (Charles LeMaire and Edward Stevenson)

- Best Music (Alfred Newman)

- Best Writing (Philip Dunne)

References

- ↑ Sheldon Hall, Epics, Spectacles, and Blockbusters: A Hollywood History Wayne State University Press, 2010 p 137

- ↑ "All Time Domestic Champs", Variety, 6 January 1960 p 34

- ↑ Aubrey Solomon, Twentieth Century-Fox: A Corporate and Financial History Rowman & Littlefield, 2002 p 223

- ↑ Richards, Jeffrey. Hollywood's Ancient Worlds, p.102, A&C Black, 2008 ISBN 9781847250070

- ↑ "David and Bathsheba". Retrieved 2006-04-27.

- ↑ Meyer, Stephen C., "Epic Sound: Music in Postwar Hollywood Biblical Films", pp.57-60, Indiana University Press, 2014 ISBN 9780253014597

- ↑ 'The Top Box Office Hits of 1951', Variety, January 2, 1952

- ↑ "A Biblical Tale is Unfolded", August 15, 1951

- ↑ Aljunied, Syed Muhd Khairudin. Colonialism, Violence and Muslims in Southeast Asia, p.103, Routledge, 2009 ISBN 9781134011599

- ↑ Solomon, Jon. The Ancient World in the Cinema, Yale University Press, 2001 ISBN 9780300083378

- ↑ Garland, David E.; Garland, Diana R. "Bathsheba's Story: Surviving Abuse and Loss" (PDF). Baylor University. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ↑ Reinhartz, Adele. "David and Bathsheba", Bible and Cinema: Fifty Key Films, pp.79-80, Routledge, 2013 ISBN 9780415677202

- ↑ Babington, Bruce and Evans, Peter William. "Henry King's 'David and Bathsheba (1951)'", Biblical Epics: Sacred Narrative in the Hollywood Cinema, Manchester University Press, 1993 ISBN 9780719040306

- ↑ "NY Times: David and Bathsheba". NY Times. Retrieved 2008-12-21.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to David and Bathsheba (1951 film). |