Astarté (opera)

Astarté is an opera in four acts and five scenes by Xavier Leroux to a libretto by Louis de Gramont. It was premiered at the Opéra de Paris on 15 February 1901, directed by Pedro Gailhard.[1]

Roles

| Role | Voice type | Premiere cast, 15 February 1901 (Conductor: Paul Taffanel) |

|---|---|---|

| Omphale | contralto | Meyrianne Héglon |

| Heracles | tenor haute-contre | Albert Alavarez |

| Phur | Bass-baritone | Francisque Delmas |

| Hylas | tenor | Léon Laffite |

| Euphanor | bass | Juste Nivette |

| Corybas | tenor | Georges Joseph Cabillot |

| Déjanire | soprano | Louise Grandjean |

| Iole | soprano | Jeanne Hatto |

| Cléanthis | soprano | Vera Nimidoff |

| A maid | soprano | Madeleine Mathieu |

Synopsis

Act 1

Heracles, Duke of Argos, will undertake a new campaign to destroy the infamous cult of the goddess Astarte. He will go to Lydia, in order to exterminate the queen Omphale, cruel and indecent sectarian of this goddess. Nothing can hold him back, not even the love of his wife Deianira. She wants to use a talisman to warn him against Omphale's seductions, which she fears. This talisman is the famous tunic of the centaur Nessos that the latter gave her, telling her that when Hercules dressed it, he would unerringly return to her. She therefore instructs Iole, her ward, to follow in her husband's footsteps and give her the box containing the bloody tunic.

Act 2

Hercules arrived with his people in Lydia, under the walls of Sardis. Hercules and his warriors are outside the city gates. Hercules leaves for a moment, then the women of Sardis take the opportunity to charm his soldiers, are followed obediently by them and drag them into the city singing and dancing, so that when Hercules returns he finds no one but the high priest Phur, who invites him to enter himself.

Act 3

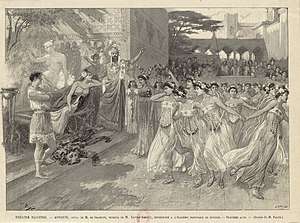

Hercules is in the palace of Omphale, where he comes to break everything. Only, when he is in the presence of Omphale, he throws down his dagger, and god became man, falls to the knees of the goddess who became woman. Indeed, she, in love and pride, demands that the entire city witness such an astonishing submission. While Hercules remains prostrate, Phur performs the ceremony of the cult of Astarte. First they are serious rites, slow dances, then, little by little, an immense furious joy seizes the priests and priestesses, courtesans and guards and it is the mystical and frenetic orgy of passion and possession. Omphale extends her arms to Hercules who rushes there.

Act 4

In the morning, Hercules and Omphale sing of their happiness in a triumphant way. The lover had never known such exhilaration; the lover had never shuddered under such an embrace. Phur disturbs this agreement. He shows Hercules the fragility of such ties that only marriage would make lasting. Omphale, to whom the thing is proposed, does not want to consent to it and, in the face of the anger caused by her refusal, she asks Astarte to put an end to this embarrassing adventure. Iole, who was brought in, immediately stepped forward, disguised as a boy. She explains the mission she is in charge of and Omphale, who guesses her sex and calls her Eros' sweet sister, allows her to accomplish it, on the condition that she stays with her and never leaves her. Their voices unite tenderly and Hercules, now dressed in the magical tunic and in the grip of the intolerable suffering of fire, screams and twists. He throws shreds of red cloth against the walls that are burning. And the city also burns and hearts and bodies are set on fire and it is to Lesbos that Omphale now returns to worship Astarte and glorify all lust.

Critics at the premiere

Astarté was favourably received upon its release. Alfred Bruneau, the critic of Le Figaro applauded the work and wrote

This score is frankly, categorically an opera score. Quite numerous and characteristic themes are recalled from page to page, especially in the first act. This act is a kind of fresco of superb intensity of colour, of superb brilliance: The brass bands that, from the theatre, respond to the orchestra, the heroic songs of Hercules, Deianira's deploration, her invocation to the fire, have an extraordinary movement, an extraordinary power. The farewells of the husband to the wife, widely, nobly declaimed and where Gluck's breath seems to pass are magnificent. I don't like the orientalism of the second painting and I must admit that the long and passionate duets that follow didn't seem so well inspired to me. They lack what would have been essential there, the variety in the feeling. But religious and orgiastic ceremonies, the final choir are not to be disdained.[2]

Arthur Pougin is not sweet and seemingly responding to Bruneau wrote in Le Ménestrel:

This strange play has very few scenic or dramatic qualities. In the first act, Hercules is with Deianira; in the second, he only appears; in the third and fourth, he is constantly with Omphale. We understand the few varieties of situations and the few elements they offer to the musician. In the first act, there is Hercules' call to his warriors, and in the second, the scene of seduction exerted on them by the women of Sardis. But these are scenic episodes, not dramatic situations. The work is conceived in the pure Wagnerian system, with endless stories, eternal dialogues without the voices ever marrying, and leitmotivs. There is even a terrible one, that of Hercules, which visibly haunted the composer's mind, and which makes him shudder when he returns periodically, attacked by the trumpets in their highest notes. It goes without saying that the author has kept himself from writing something that looks like a "piece". And yet, see the irony, he placed in the first act in Hercules' mouth, on these words addressed to Deianira: Here is the moment of the supreme farewells, a cantabile of a penetrating feeling, with, oh surprise! return of the motif serving as a conclusion, and the audience was so charmed that the whole room heard a whisper of satisfaction and pleasure.[3]

Paul Milliet of Le Monde artiste was very favourable and wrote:

Xavier Leroux has musical eloquence, and his ardour borrows a singular expression from the leitmotiv. In his work, the conductive patterns are clear even in their transformations. The whole first act is superb in terms of anger and colour. The declamation of Hercules is high, and the farewells of Deianira are of remarkable nobility. These premises of the drama have magnificence and power. The following two acts are of a completed grace; the scene of seduction played by Omphale; the religious ceremony where everything else, the setting, the light and the staging, is admirably combined to reproduce the phallic and orgiastic cults of Asia; the awakening of lovers; the prayer to the divine Astarte, The score of Astarté is of a beautiful and strong inspiration; and it deserves the warm applause that welcomed it. Mr. Xavier Leroux honours the French school, and his success delights me in every way.[4]

More modern analysis

Alex Ross of The New Yorker delivers a different view:

Omphale is the priestess of Astarte's Saphic cult, and Hercules is shown in drag, observing what appears to be a lesbian orgy. Hercules intends to put an end to debauchery but falls in love with Omphale instead. ... The opera ends with the priestess reconstituting her Sapphic circle on the island of Lesbos, as a chorus sings: "Glory to pleasure".

and Ross indicates that the German magazine Jahrbuch für sexuelle Zwischenstufen noted: "Astarté is probably the first opera to be performed, and generally the first theatre piece, in which lesbian love is represented."[5]

References

- ↑ Paul Milliet (17 February 1901). "Première représentation d'Astarté". Le Monde artiste (in French) (7). p. 2. Retrieved 18 September 2018. .

- ↑ Alfred Bruneau (16 February 1901). "Les Théâtres". Le Figaro (in French) (47). p. 4. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ↑ Arthur Pougin (17 February 1901). "Semaine théâtrale". Le Ménestrel (in French) (3647). pp. 50–52. Retrieved 18 September 2018. .

- ↑ Paul Milliet (24 February 1901). "Astarté". Le Monde artiste (8). pp. 115–117. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ↑ Alex Ross (27 July 2017). "The Decline of Opera Queens and the Rise of Gay Opera". The New Yorker. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

Sources

- Astarté : partition intégrale (piano-chant) on the site of the Médiathèque musicale de Paris.

- Camille Bellaigue (1901). "Revue musicale. – Astarté à l'Opéra; La Fille de Tabarin à l'Opéra-Comique". (in French). 5e période, tome 2. Paris. pp. 219–228. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

External links

- Astarté: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)