Asian water monitor

| Water monitor | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Family: | Varanidae |

| Genus: | Varanus |

| Species: | V. salvator |

| Binomial name | |

| Varanus salvator (Laurenti, 1768) | |

Varanus salvator, commonly known as the water monitor or common water monitor,[1] is a large lizard native to South and Southeast Asia. Water monitors are one of the most common monitor lizards found throughout Asia. They range from Sri Lanka and coastal northeast India to Indochina, the Malay Peninsula, and various islands of Indonesia, living in areas close to water. The Asian water monitor was described by Laurenti in 1768 and is among the largest squamate lizards in the world.[2]

The species is known as Malayan water monitor, Asian water monitor (or kabaragoya, denoting a Sri Lankan subspecies with distinct morphological features), common water monitor, two-banded monitor, and as rice lizard, ring lizard, plain lizard and no-mark lizard, as well as simply "water monitor".[3]

Description

The water monitor is a large species of monitor lizard. Breeding maturity is attained for males when they are a relatively modest 40 cm (16 in) long and weigh 1 kg (2.2 lb), and for females at 50 cm (20 in). However, they grow much larger throughout life, with males being larger than females.[4] Adults rarely exceed 1.5–2 m (4.9–6.6 ft) in length,[5] but the largest specimen on record, from Sri Lanka, measured 3.21 m (10.5 ft). A common mature weight of V. salvator can be 19.5 kg (43 lb).[4][6] However, 80 males killed for the leather trade in Sumatra averaged only 3.42 kg (7.5 lb) and 56.6 cm (22.3 in) snout-to-vent and 142 cm (56 in) in total length; 42 females averaged only 3.52 kg (7.8 lb) and 59 cm (23 in) snout-to-vent and 149.6 cm (58.9 in) in total length,[7] although unskinned outsized specimens weighed 16 to 20 kg (35 to 44 lb). Another study from the same area by the same authors similarly estimated mean body mass for mature specimens at 20 kg (44 lb)[8] while yet another study found a series of adults to weigh 7.6 kg (17 lb).[9] The maximum weight of the species is over 50 kg (110 lb).[10] In exceptional cases, the species has been reported to attain 75 to 90 kg (165 to 198 lb), though most such reports are unverified and may be unreliable. They are the world's second-heaviest lizard, after the Komodo dragon.[7][11] Their bodies are muscular, with long, powerful, laterally compressed tails. The scales in this species are keeled; scales found on top of the head have been noted to be larger than those located on the back. Water monitors are often defined by their dark brown or blackish coloration with yellow spots found on their underside- these yellow markings have a tendency to disappear gradually with age. This species is also denoted by the blackish band with yellow edges extending back from each eye. These monitors have very long necks and an elongated snout. They use their powerful jaws, serrated teeth and sharp claws for both predation and defense. In captivity, Asian water monitors' life expectancy has been determined to be anywhere between 11–25 years depending on conditions, in the wild it is much less.[12][13]

Taxonomy

Asian water monitors fall within the kingdom: Animalia, phylum: Chorodata, class: Reptilia, order: Squamata, family: Varanidae, genus: Varanus, and species: V. salvator.[14] The family: Varanidae contains nearly 80 species of monitor lizards, all of which belong to the genus: Varanus. This genus has been proven to show the widest size range of any vertebrate genus.[15] There is a significant amount of taxonomic uncertainty within this species complex. Morphological analyses have begun to unravel this taxonomic uncertainty but molecular studies are needed to test and confirm the validity of this evidence. Research initiatives such as these are very important for changes in conservation assessments.[14]

Range

Asian water monitors are extremely widespread throughout southern and Southeastern Asia. The species has an upper limit of 1800 meters above sea level, that being said, it is typically considered to be a lowland species common only in areas up to 600 meters yet rare at altitudes above 100 metes. Asian water monitor populations are native to: Bangladesh; Cambodia; China (Guangxi, Hainan, Yunnan); Hong Kong; India (Andaman Is., Nicobar Is.); Indonesia (Bali, Java, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, Sumatera); Lao People's Democratic Republic; Malaysia (Peninsular Malaysia); Myanmar; Singapore; Sri Lanka; Thailand; Vietnam.[14]

Etymology

The generic name Varanus is derived from the Arabic waral (ورل), which translates as "monitor". The specific name is the Latin word for "saviour", denoting a possible religious connotation.[16] The water monitor is occasionally confused with the crocodile monitor (V. salvadorii) because of their similar scientific names.[17]

In Thailand, the local word for a water monitor, hia (เหี้ย), is used as an insulting word for bad and evil things, including bad persons. The word is also thought to bring bad luck, so some people prefer to call the animals 'silver-and-gold' (ตัวเงินตัวทอง) to avoid the jinx.

The origin of this offensive meaning can be traced back to a time when more people lived in rural areas in close proximity to monitor lizards. Traditionally, Thai villagers lived in two-story houses; the top floor was for living, while the ground floor was designed to be a space for domestic animals such as pigs, chickens, and dogs. Water monitors would enter the ground floor and eat or maim the domestic animals, also hence the other name dtua gin gai (ตัวกินไก่ ‘chicken eater’) or nong chorakae (น้องจระเข้ ‘younger brother of crocodile’, ‘little crocodile’)[18] and even sometimes called ta kuat (ตะกวด), which in fact refers to a Bengal monitor (V. bengalensis), a different species.[18]

In Indonesian and Malay, the water monitor is called biawak air,[19] to differentiate it from the biawak pasir ("sand lizard"), Leiolepis belliana.[20]

Subspecies

- The Asian water monitor, V. s. salvator, the nominate subspecies, is now restricted to Sri Lanka, where it is known as the kabaragoya (කබරගොයා) in Sinhala and kalawathan in Tamil.

- The Andaman Islands water monitor, V. s. andamanensis, is found on the Andaman Islands; the type locality is Port Blair, Andaman Islands.

- The two-striped water monitor, V. s. bivittatus, is common to Java, Bali, Lombok, Sumbawa, Flores, Ombai (Alor), Wetar, and some neighbouring islands within the Sunda arch, Indonesia; the type locality is Java (designated by Mertens 1959).

- The black water monitor, V. s. komaini, from Thailand (type locality: Amphoe La-ngu, Satun Prov., Thailand, and Thai-Malaysian border area), was formerly a subspecies, but now is regarded as a synonym of V. s. macromaculatus.[21] It is known as the "black dragon" or "black water monitor" (มังกรดำ, เหี้ยดำ) in Thai[22]

- The Southeast Asian water monitor, V. s. macromaculatus (type locality: Siam [Thailand]), is found in mainland Southeast Asia, Singapore, Sumatra, Borneo, and smaller associated offshore islands.[21]

- Ziegler's water monitor, V. s. ziegleri, is from Obi Island.

- Varanus cumingi, Varanus marmoratus, and Varanus nuchalis were classified as subspecies until 2007, when they were elevated to full species.[21][23]

Habitat and ecology

Asian water monitors are semiaquatic and opportunistic; they inhabit a variety of natural habitats though predominantly this species resides in primary forests and mangrove swamps. It has been noted that the presence of humans does not deter these monitors from areas of human disturbance. In fact, they have been known to adapt and thrive in agricultural areas as well as cities with canal system (such as Sri Lanka, where they are not hunted or persecuted by humans). This species does not thrive in habitats with extensive loss of natural vegetation and aquatic resources. Habitats that are considered to be most important to this species are mangrove vegetation, swamps, wetlands, and altitudes below 1000 meters.[14]

Behavior and diet

.jpg)

Water monitors defend themselves using their tails, claws, and jaws. They are excellent swimmers, using the raised fin on their tails to steer through water. They are carnivores, and consume a wide range of prey. They are known to eat fish, frogs, rodents, birds, crabs, and snakes.[16] They have also been known to eat turtles, as well as young crocodiles and crocodile eggs.[24] Water monitors have been observed eating catfish in a fashion similar to a mammalian carnivore, tearing off chunks of meat with their sharp teeth while holding it with their front legs and then separating different parts of the fish for sequential consumption.[25]

In dominantly aquatic habitats their semi-aquatic behavior is considered to provide a measure of safety from predators. This paired with their generalist diet is thought to contribute to their ecological plasticity.[14] When hunted by predators such as the King cobra (Ophiophagus Hannah) they will climb up trees using their powerful legs and claws. If this strategic evasion is not enough to avoid danger, they have also been known to jump from trees into streams for safety- a similar behavior to that of the Green iguana (Iguana iguana).[12]

Like the Komodo dragon, the water monitor will often eat carrion.[16][26] They have a keen sense of smell and can smell a carcass from far away. They are known to feed on dead human bodies. While on the one hand their presence can be helpful in locating a missing person in forensic investigations, on the other hand they can inflict further injuries to the corpse, complicating ascertainment of the cause of death.[27]

The first description of the water monitor and its behavior in English literature was made in 1681 by Robert Knox, who had had carefully observed the lizard during his long confinement in the Kingdom of Kandy: “There is a Creature here called Kobberaguion, resembling an Alligator. The biggest may be five or six feet long, speckled black and white. He lives most upon the Land, but will take the water and dive under it: hath a long blue forked tongue like a sting, which he puts forth and hisseth and gapeth, but doth not bite nor sting, tho the appearance of him would scare those that knew not what he was. He is not afraid of people, but will lie gaping and hissing at them in the way, and will scarce stir out of it. He will come and eat Carrion with the Dogs and Jackals, and will not be scared away by them, but if they come near to bark or snap at him, with his tail, which is long like a whip, he will so slash them, that they will run away and howl.”[28]

Water monitors should be handled with care since they have many sharp teeth and can give gashing bites that can sever tendons and veins, causing extensive bleeding. The bite of a large pet water monitor was described by its American owner as being worse than that of a rattlesnake.[29]

Venom

The possibility of venom in the genus Varanus is widely debated. Previously, venom was thought to be unique to Serpentes (snakes) and Heloderma (venomous lizards). The aftereffects of a Varanus bite were thought to be due to oral bacteria alone, but recent studies have shown venom glands are likely to be present in the mouths of several, if not all, of the species. The venom may be used as a defensive mechanism to fend off predators, to help digest food, to sustain oral hygiene, and possibly to help in capturing and killing prey.[30][31] Varanus salvator has not yet been specifically tested, but its bites are likely to be consistent with the venomous bites from other varanid lizards.

Conservation

Monitor lizards are traded globally and are the most common type of lizard to be exported from Southeast Asia, with 8.1 million exported between 1998 and 2007.[32] Water monitors are used by humans for a variety of purposes and are one of the most exploited varanids.[33] They are hunted predominantly for their skins for use in fashion accessories such as shoes, belts and handbags which are shipped globally, with as many as 1.5 million skins traded annually.[33] Other uses include as a perceived remedy for common skin ailments and eczema,[34] a perceived aphrodisiaca,[35] novelty food in Indonesia[36] and as pets.[37]

In Nepal's Chitwan National Park it is a protected species under the Wild Animals Protection Act of 2002. In Hong Kong, it is a protected species under Wild Animals Protection Ordinance Cap 170. In Malaysia, this species is one of the most common wild animals, with numbers comparable to the population of macaques there. Although many fall victim to humans via roadkill and animal cruelty, they still thrive in most states of Malaysia, especially in the shrubs of the east coast states such as Pahang and Terengganu. In Thailand, all monitor lizards are protected species.[37] They are still very common in large urban areas in Thailand and are frequently seen in Bangkok canals and parks. Because of this, water monitors are currently listed in the Least Concern category of the IUCN Red List and in CITES Appendix 2.[12] These classifications have been made on the basis that this species maintains a geographically wide distribution, can be found in a variety of habitats, adapts to habitats disturbed by humans, and is abundant in portions of its range despite large levels of harvesting.[14]

Loss of habitat and hunting has exterminated water monitors from most of mainland India. In other areas they survive despite being hunted, due in part to the fact that larger ones, including large females that breed large numbers of eggs, have tough skins that are not desirable.[3]

In Sri Lanka, they are protected by locals who value their predation of "crabs that would otherwise undermine the banks of rice fields".[3] They are also protected due to eating venomous snakes.[38]

Gallery

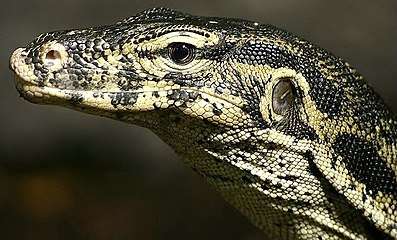

Closeup of the head

Closeup of the head Closeup of split tongue

Closeup of split tongue Resting on tree limb

Resting on tree limb A hatchling

A hatchling Walking on pavement

Walking on pavement Showing its split tongue

Showing its split tongue Head closeup

Head closeup

References

- 1 2 Bennett, D.; Gaulke, M.; Pianka, E. R.; Somaweera, R. & Sweet, S. S. (2010). "Varanus salvator". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2010: e.T178214A7499172. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2010-4.RLTS.T178214A7499172.en. Retrieved 5 January 2018.

- ↑ Koch, A. (2007). "Morphological Studies on the Systematics of South East Asian Water Monitors (Varanus Salvator Complex): Nominotypic Populations and Taxonomic Overview". Mertensiella. 16: 109–180.

- 1 2 3 Ria Tan (2001). "Mangrove and wetland wildlife at Sungei Buloh Wetlands Reserve: Malayan Water Monitor Lizard". Naturia.per.sg. Retrieved 2015-09-15.

- 1 2 Shine, R.; Harlow, P. S.; Keogh, J. S. (1996). "Commercial harvesting of giant lizards: The biology of water monitors Varanus salvator in southern Sumatra". Biological Conservation. 77 (2–3): 125–134. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(96)00008-0. Retrieved 2013-06-09.

- ↑ Pianka, King & king. Varanoid lizards of the world. 2004

- ↑ Water Monitor Lizard (Varanus salvator) at Pak Lah’s House | Mutakhir. Wildlife.gov.my (2012-02-23). Retrieved on 2012-08-22.

- 1 2 Shine, R.; Harlow, P. S.; Keogh, J. S. (1996). "Commercial harvesting of giant lizards: The biology of water monitors Varanus salvator in southern Sumatra". Biological Conservation. 77 (2): 125–134. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(96)00008-0.

- ↑ Shine, R., & Harlow, P. S. (1998). Ecological traits of commercially harvested water monitors, Varanus salvator, in northern Sumatra. Wildlife Research, 25(4), 437-447.

- ↑ Dryden, G. L.; Green, B.; Wikramanayake, E. D.; Dryden, K. G. (1992-02-03). "Energy and water turnover in two tropical varanid lizards, Varanus bengalensis and V. salvator". Copeia. 1992 (1): 102–107. doi:10.2307/1446540.

- ↑ Water Monitor – Varanus salvator : WAZA : World Association of Zoos and Aquariums. WAZA. Retrieved on 2012-08-22.

- ↑ Wood, Gerald (1983). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- 1 2 3 "Asian Water Monitor". Wildlife Facts. Retrieved 2017-12-01.

- ↑ "Water Monitor Care Sheet | Black Dragon Care Sheet | Varanus salvator Care Sheet | Vital Exotics". www.vitalexotics.com. Retrieved 2017-12-01.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Varanus salvator (Common Water Monitor)". www.iucnredlist.org. Retrieved 2017-12-01.

- ↑ "Parietal eye - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2017-12-01.

- 1 2 3 Robert George Sprackland (1992). Giant lizards. Neptune, NJ: T.F.H. Publications. ISBN 0-86622-634-6.

- ↑ Netherton, John; Badger, David P. (2002). Lizards: A Natural History of Some Uncommon Creatures—Extraordinary Chameleons, Iguanas, Geckos, and More. Stillwater, MN: Voyageur Press. pp. 140–141. ISBN 0-7603-2579-0.

- 1 2 -, ship9960 (November 2, 2009). "คำหยาบคายของคนไทยเริ่มมาจากไหนครับ" (in Thai). Pantip.com. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Journal of Biosciences, Volumes 15-16 Universiti Sains Malaysia, 2004

- ↑ The Hope Reports, Volume 4 private circulation, 1903

- 1 2 3 Koch, A., M. Auliya, A. Schmitz, U. Kuch & W. Böhme. (2007). Morphological Studies on the Systematics of South East Asian Water Monitors (Varanus salvator Complex): Nominotypic Populations and Taxonomic Overview. pp. 109–180. In Horn, H.-G., W. Böhme & U. Krebs (eds.), Advances in Monitor Research III. Mertensiella 16, Rheinbach.

- ↑ "โชว์"เหี้ยดำ"สัตว์หายากชนิดใหม่". tnews.teenee (in Thai). June 8, 2007. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ "Soterosaurus: Mindanao Water Monitor". monitor-lizards.net. Archived from the original on 31 July 2012. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ↑ Whitaker, Rom (1981). "Bangladesh – Monitors and turtles". Hamadryad. 6 (3): 7–9.

- ↑ Stanner, Michael (2010). "Mammal-like Feeding Behavior of Varanus salvator and its Conservational Implications" (PDF). Biawak. 4 (4): 128–131.

- ↑ Rahman, K. M. M.; Rakhimov, I. I.; Khan, M. M. H. (2017). "Activity budgets and dietary investigations of Varanus salvator (Reptilia: Varanidae) in Karamjal ecotourism spot of Bangladesh Sundarbans mangrove forest". Basic and Applied Herpetology. 31: 45–56. doi:10.11160/bah.79.

- ↑ Gunethilake Kmtb, Vidanapathirana M (2016). "Water monitors; Implications in forensic death investigations". Medico-Legal Journal of Sri Lanka. 4 (2): 48–52. doi:10.4038/mljsl.v4i2.7338.

- ↑ Knox, Robert, An Historical Relation of the Island of Ceylon in the East Indies: Together With, an Account of the Detaining in Captivity the Author, and Divers, Other Englishmen Now Living There, and of the Author's Miraculous Escape, London 1817 (reprint), p. 59.

- ↑ Durham. Dave. “Worst Monitor Lizard Bite!”. Accessed on 15.8.2017 on https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gmn4GGQaVuc

- ↑ Arbuckle, Kevin. Ecological Function of Venom in Varanus, with a Compilation of Dietary Records from the Literature, Biowak, Vol. 3(2), pp. 46-56, 2009

- ↑ Yong, Ed. The Myth of the Komodo Dragon’s Dirty Mouth, National Geographic, 06/27/2013. Accessed 15.8.2017.

- ↑ Nijman, Vincent (2010). "An overview of international wildlife tradefrom Southeast Asia". Biodiversity and Conservation. doi:10.1007/s10531-009-9758-4 – via Researchgate.

- 1 2 "Varanus salvator (Common Water Monitor)". www.iucnredlist.org. Retrieved 2017-02-02.

- ↑ Uyeda at al (2014). "Water Monitor Lizard (Varanus salvator) Satay: A Treatment for Skin Ailments in Muarabinuangeun and Cisiih, Indonesia". Biawak.

- ↑ Nijman, Vincent (2016). "Perceptions of Sundanese Men Towards the Consumption of Water Monitor Lizard Meat in West Java, Indonesia". Biawak – via ResearchGate.

- ↑ Nijman, Vincent (2015). "Water Monitor Lizards for Sale as Novelty Food in Java, Indonesia" (PDF). Biawak.

- 1 2 Komsorn Lauprasert & Kumthorn Thirakhupt (August 2001). "Species Diversity, Distribution and Proposed Status of Monitor Lizards (Family Varanidae) in Southern Thailand" (PDF). The Natural History Journal of Chulalongkorn University. Chulalongkorn University. 1 (1): 39–46. Retrieved 2015-01-26.

- ↑ Wirz, Paul. Exorcism and the Art of Healing in Ceylon, Leiden, 1954, p. 238.

Further reading

- Das, Indraneil (1988). "New evidence of the occurrence of water monitor (Varanus salvator) in Meghalaya". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 86: 253–255.

- Deraniyagala, P. E. P. (1944). "Four New Races of the Kabaragoya Lizard Varanus salvator". Spolia Zeylanica. 24: 59–62.

- Pandav, Bivash (1993). "A preliminary survey of the water monitor (Varanus salvator) in Bhitarkanika Wildlife Sanctuary, Orissa". Hamadryad. 18: 49–51.

External links

- Animal Diversity Web

- JCVI.org

- The New Reptile Database

- Photos – water monitor swimming